Omar Velázquez: Shaping Tropical Darkness

It is clear to me that the core of my work resides in an area of my mind which can very well be approached geographically […]. Perhaps this voyage of discovery was my own way of coming to terms with Puerto Rico. A very close and foreign island—more physical than emotional, but more fantastic than real.—Rafael Ferrer

Written by Carla Acevedo-Yates

Essay

In the Caribbean, vision is often compromised: the quality of light, verdant vegetation, and exuberant natural beauty often obscure the dark, colonial histories inscribed on the landscape. This obfuscation has long been replicated in the construction of images that define the region as an object of desire—and a space of leisure and play by tourists—to satisfy a Western gaze. Yet distance allows a certain type of visibility that proximity renders opaque, as seen in the work of Omar Velázquez (Puerto Rican, b. 1984). Velázquez is an artist and musician who explores the tropes and conventions of Western painting, as well as the intersection of music, painting, and folklore, to create an intensely coded body of work that gives shape to complex experiences of colonialism, memory, and diaspora. His scenes of colonial encounters are structured by formal technique, such as the use of acrylic and oil paint to create distance and perspective between figure and ground. But they are also informed by personal and spiritual concerns, including Taíno Indigenous beliefs and memories, dreams, and drives through rural Puerto Rico. These strategies place his work within a broad genealogy of Puerto Rican artists whose constant departures and returns, both geographic and stylistic, have defined an aesthetic practice rooted in sociopolitical concerns. They also point to the intricate relationship between vision, artistic practice, and politics, where painting is a creative act that takes the viewer through spatial and temporal layers to see beyond the surface in new ways.

Velázquez was born and raised in Isabela, Puerto Rico, a municipality on the northwest coast, surrounded by lush mountains, that is also the ancestral home of Mabodamaca, a chief of the Taíno Indigenous people native to Puerto Rico. By focusing on the rural landscape of the island as well as the history of Indigenous and postcolonial musical traditions in the region, Velázquez reimagines traditional painting genres such as landscape, still life, and portraiture, equally referencing and pushing against the legacies of Western painting in relation to folk art forms, including string instruments. Although his work engages with global art histories that extend to European and North American painting, three Puerto Rican artists have particularly influenced his recent body of work: master painter Francisco Oller y Cestero (1833–1917), luthier and self-taught artist Carmelo Martell Luciano (1907–1990), and artist Rafael Ferrer (b. 1933), whose work plays with the distinctions between contemporary art and folk forms.1 Within the aforementioned painting genealogy, Velázquez's work distinguishes itself by the exclusion of human figures. Instead, he focuses on the anthropomorphic qualities of endemic flora and fauna, developing a visual language that hinges on the surreal. At first glance, his paintings seduce the viewer by employing a vibrant color palette that references stereotypical representations of the Caribbean. Upon closer consideration, however, there is something sinister about the images he creates: an ominous feeling that something is about to happen, a narrative that is never fully completed or resolved.

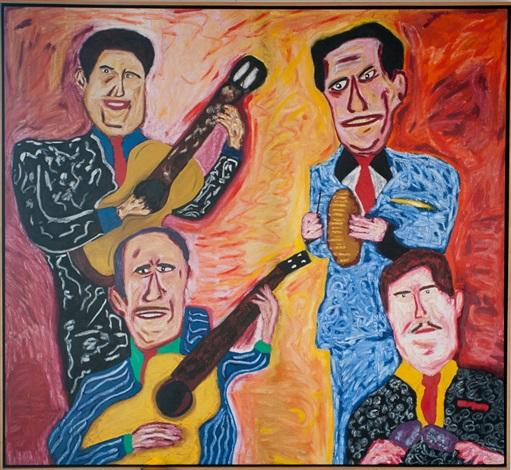

Personal experiences, both in Puerto Rico and the United States, and encounters with specific works of art by other artists are important references for Velázquez, who moved to Chicago from Puerto Rico in 2014 to pursue graduate studies in painting at the School of the Art Institute.2 While there, an encounter with a work by Rafael Ferrer at the MCA Chicago in 2016 inspired a new direction in his work. The artwork that immediately caught his attention was _Portrait of Charles Darwin as a Fuegian Ceremonial Mask_ (1972), a sculpture where Ferrer used a snare drum as a surface to paint and assemble fur, leather, and plastic to resemble a face or a mask. Ferrer, who worked as a professional percussionist for many years, has often featured images of quartets, guitars, and other instruments in his work, and has an extensive history with Chicago.3 Ferrer's colorful, figurative scenes and expressive brushstrokes in paintings such as El cuarteto (1981, fig. 1) also resonated with Velázquez, who found common ground in Ferrer's “messy and excessive imagery.”4 Velázquez is himself a musician interested in the history of string instruments. Classically trained as a saxophone player in his teens, he now plays the guitar in punk and doom heavy-metal bands: a subgenre of heavy metal defined by slow tempos and muddled sounds, whose lyrics usually evoke a sense of impending doom and overall hopelessness.

Rafael Ferrer, El cuarteto, 1981

Courtesy of Adam Baumgold GalleryThe relationship between music and painting proved definitive for Velázquez during his education. While studying printmaking at the University of Puerto Rico Río Piedras, Velázquez frequented Francisco Oller's seminal painting El velorio (The Wake) (c. 1893, fig. 2), which is on permanent view at the Museo de Historia, Antropología y Arte. Although the main scene describes a baquiné (the wake of a child), Velázquez's attention turned to a mysterious figure receded into the shadows on the left side of the painting, who looks away from the main scene while playing a small guitar. The instrument this man holds is a tiple, a string instrument indigenous to Puerto Rico that is similar in size and form to a mandolin or lute.5 Alongside the cuatro and the bordonúa (a small to mid-size guitar and a low-pitched, deep body bass guitar, respectively), the tiple is part of the orquesta jíbara (or country orchestra), a genre of music traditionally played in rural Puerto Rico. Now mostly heard during Christmas, traditional festivities, and special occasions, this music summons a nostalgia for Puerto Rican traditions that have been receding to the background since the mid-twentieth century. Both the instruments of orquesta jíbara and the musicians and culture of the art form itself became critical subject matter for Velázquez, whose work frequently features the tiple and the cuatro.

Francisco Oller, “El velorio” (The Wake), ca. 1893. Museo de la Universidad de Puerto Rico. Oil on canvas 8 x 3 ft

MCABeyond references to folk music and string instruments, Velázquez's painting is informed by Oller in other ways, particularly his use of Western painting genres as a tool to address sociopolitical topics. Oller, who would become the only Latin American artist who contributed to the development of the artistic style later known as Impressionism, studied painting in Paris from 1858 to 1865 with fellow students Claude Monet, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, and Frédéric Bazille.6 His education in the European painting tradition was formative, yet as a social realist painter and impressionist his work focused on everyday scenes in rural Puerto Rico. When Oller returned to Puerto Rico in the early 1880s, he encountered an island in severe economic, political, and social deterioration, where liberals and nationalists were persecuted by colonists. He proceeded to paint El velorio, one of the most incisive critiques of the impact of Spanish colonial rule on Puerto Rican society, which deftly employs a formalism that belies a sharp political message. Admittedly influenced by Gustave Courbet's social realism and distinctively earthy palette, El velorio portrays a genre scene in rural Puerto Rico, where the sorrowful occasion is overshadowed by the mourners' excitement as they watch a roasted pig being brought in on a stick. Only a sole figure, a Black beggar in the center of the painting, looks directly at the deceased child.

Velázquez's interest in music and folk art led him to the Museo de la Música Puertorriqueña in Ponce, Puerto Rico, where he saw the guitar sculptures of self-taught artist and luthier Carmelo Martell Luciano, who created the "rooster cuatro," the "duck cuatro," and his masterpiece: a cuatro in the shape of the island of Puerto Rico.7 These objects, which are also functional instruments, are meticulously carved and painted. In the case of the “map cuatro,” Martell Luciano covered the surface with detailed images of places on the island and prominent Puerto Rican figures. As an homage to Martell Luciano and Catalino Vélez, a luthier from Velázquez's hometown who taught him how to make string instruments, Velázquez started making a series of guitar sculptures shaped like tropical fruits such as avocado, pumpkin, and papaya (fig. 3). Hand-carved out of endemic avocado and mango tree wood, these sculptures can also be played as traditional instruments. Although a relatively recent addition to his visual repertoire, Velázquez's instrument-building practice dialogues with the history of painting in its display: the artist often places instruments in compositional arrangements that bear resemblance to a still life.

Chicago Works: Omar Velázquez, MCA Chicago. December 22, 2020–July 25, 2021

Photo: Nathan Keay, © MCA ChicagoThese sculptures occupy a central place in Velázquez's visual vocabulary of Caribbean transculturation. The cuatro, itself a material result of cross-cultural exchange, has changed forms throughout the centuries. Initially, the cuatro was a keyhole-shaped, four-stringed instrument, hence the name “cuatro” or “four," and is part of a cultural legacy of Spanish settler colonialism.8 Although its true origin is unknown, it is believed that settlers brought the vihuela and the laúd string instruments to the Caribbean during the fifteenth century, where they evolved into the forms that we know today. In the early twentieth century, instrument makers in the northern coastal regions of Puerto Rico added additional strings—to a total ten—and changed the cuatro's shape into a form that resembles a violin. Although these instruments traditionally accompany a main singer or troubadour, Velázquez centers them in his work alongside the mountainous landscape, whose curves are replicated in the instrument's shape.

Sourcing references from Ferrer and Oller in his painting practice, Velázquez creates imagined scenes where art-historical citations collide with culturally specific sociopolitical concerns. Take Yocahú Bibí (2020, fig. 4), a painting that creolizes the Western tradition of still life to synthesize both a way of life and Puerto Rico's colonial history. Here, Velázquez creates an image of what can be described as an improvisational still life, made of elements that depend on each other for their existence and that express the resourcefulness and improvisational character of Caribbean life. Influenced by Dutch still-life painting as well as Oller's reworked take on the genre—such asStill-life with Avocados and Utensils (1890–91), which features images of tropical fruits—here, Velázquez creates an image of an unstable still life against a rural landscape. The format itself plays with painting conventions, as it is a landscape painting in the vertical orientation of a portrait. In the scene, instead of a table, a rectangular, raw wood panel is precariously held by four objects, including a Taíno ceremonial hatchet and a pata de cabra (crowbar or “goat's foot”). Resting on top, a cuatro in the shape of a papaya, a rotten banana peel, a dripping aloe leaf, and a sculpture of an alert guinea hen, who attentively oversees the evolving scene on the horizon, complete the main scene. Adding to this unusual still life, disk-like clouds that resemble flying saucers hover above a mountainous landscape, glowing against fluorescent green shades of light.9 As the guinea hen observes the arrival of potential invaders or settlers, the scene depicted on the wood panel seems to teeter on the brink of collapse, evoking a sense of impending doom.

Omar Velázquez, Yocahú Bibí, 2020. Oil and acrylic on canvas; 72 x 84 in.

Courtesy of the artist and Corbett vs. Dempsey, Chicago. Photo: Julio Lugo Rivas.Through the creation of ominous situations that sit between still life and landscape painting, Velázquez visually codifies Puerto Rico's unstable social and economic conditions, both a result of the island's colonial relationship to the United States. These precarious circumstances are worsened today by the austerity measures implemented by the United States Congress–appointed Fiscal Control Board since 2016 under Federal law PROMESA (The Puerto Rico Oversight, Management, and Economic Stability Act), which undermines the island's political and economic sovereignty by having full control over its finances, laws, and other regulations. The name Yocahú in the title of Velázquez's painting references the supreme Taíno deity of the sea and giver of yuca or cassava, a reminder of the island's dependance on agricultural imports. Puerto Rico currently imports approximately 85 percent of the food that is consumed on the island, which arrives by sea on ships that are mandated by law to be owned by the United States.10 During the 1950s, colonial relations between the island and the United States were made official through the establishment of the present-day political status known as the ELA (Free Associated State). This “new” status ushered the economy, until then mainly agricultural, into rapid industrialization under Operation Bootstrap. These economic shifts led to the displacement of rural populations to urban centers on the island, and over time made Puerto Rico reliant on agricultural imports to cover basic alimentary needs. In addition to this, the mass migration of Puerto Ricans to the United States to major cities such as Chicago and New York, motivated by the promise of job security and fueled by financial incentives offered by the government, created diasporic communities whose cultural and affective ties to the island remain to this day.

In Yocahú Bibí, the domestic, interior spaces typically associated with still-life painting are replaced by Velázquez's recurring mountainous landscapes. The shapes of these peaks are often inscribed with ghostly faces that reference the Taíno deities that, according to their mythology, live in the mountains. In fact, in Yocahú Bibí—and in other recent works—Velázquez's aesthetic impulses are guided by the physical shape and mystical qualities of the mountain as a sacred deity, hinting at the underlying presence of Indigenous beliefs about nature. Velázquez shares that “The concept of the mountain can be seen as a mystical creative attraction, an ode to the shape, the shape of the wave, the wave of the mountain, the mountain adored by natives and considered the mother and driving force for creation.”11 For the Taínos, every single thing in nature has consciousness; all things have life, including stones, plants, rivers, caves, and mountains. This consciousness is a central theme in Velázquez's work, where plants, animals, fruits, and the overall landscape have spiritual and creative attributes. The mountains depicted in Yocahú Bibí reference the Tres Picachos, a sacred mountain range to the Taíno that is located near the Caguana Indigenous Ceremonial Park in Utuado, where luthier Carmelo Martell Luciano lived and worked. The shape of the Tres Picachos also served as the formal inspiration for cemis, the three-pointed ceremonial objects fashioned by the Taíno in pottery, wood, or bone that can house as many as ten spirits. A recurring iconographic element in Velázquez's work, cemis were often buried in the ground to increase crops and were passed on through generations.

Located within a genealogy of Puerto Rican painters such as Myrna Báez, Arnaldo Roche Rabell, and Enoc Pérez, Velázquez often uses printmaking techniques to build his compositions. In his case, these techniques include drawing and cutting paper templates and using them as a matrix to create impasto reliefs on the surface of the canvas. Other traces of printmaking in his work are the hard-edged lines that organize the painting's composition and distinguish figures and shapes. Although this reference might be mistaken with the Western hard edge painting tradition of artists such as Ellsworth Kelly and Frank Stella, it is the Puerto Rican woodcut and silk screen tradition from the 1950s and sixties that the artist is referencing: works by Fifties Generation artists Eduardo Vera Cortés, Antonio Maldonado, and Carlos Raquel Rivera, most of whom seamlessly switched between printmaking and painting.12 Of particular interest for the artist is Carlos Raquel Rivera's ominous and dramatic early morning landscape painting Niebla (1965, fig. 5), where plants possess anthropomorphic qualities and the Puerto Rican countryside bears a mysterious force. Raquel Rivera's other techniques include creating depth and perspective by using a combination of oil and acrylic paint. First working on an atmospheric ground, he builds images with acrylic airbrush to create a flat, blurry, and seemingly digital background. Subsequently, he applies thick oil impasto to create tactile surfaces and, in some cases, sculptural objects that protrude into the foreground. Here, some of the marks, dots, and lines used to represent foliage create patterns that resemble the ones used by artisans on the island to make traditional carnival masks and other objects.

Carlos Raquel Rivera, Niebla, 1965

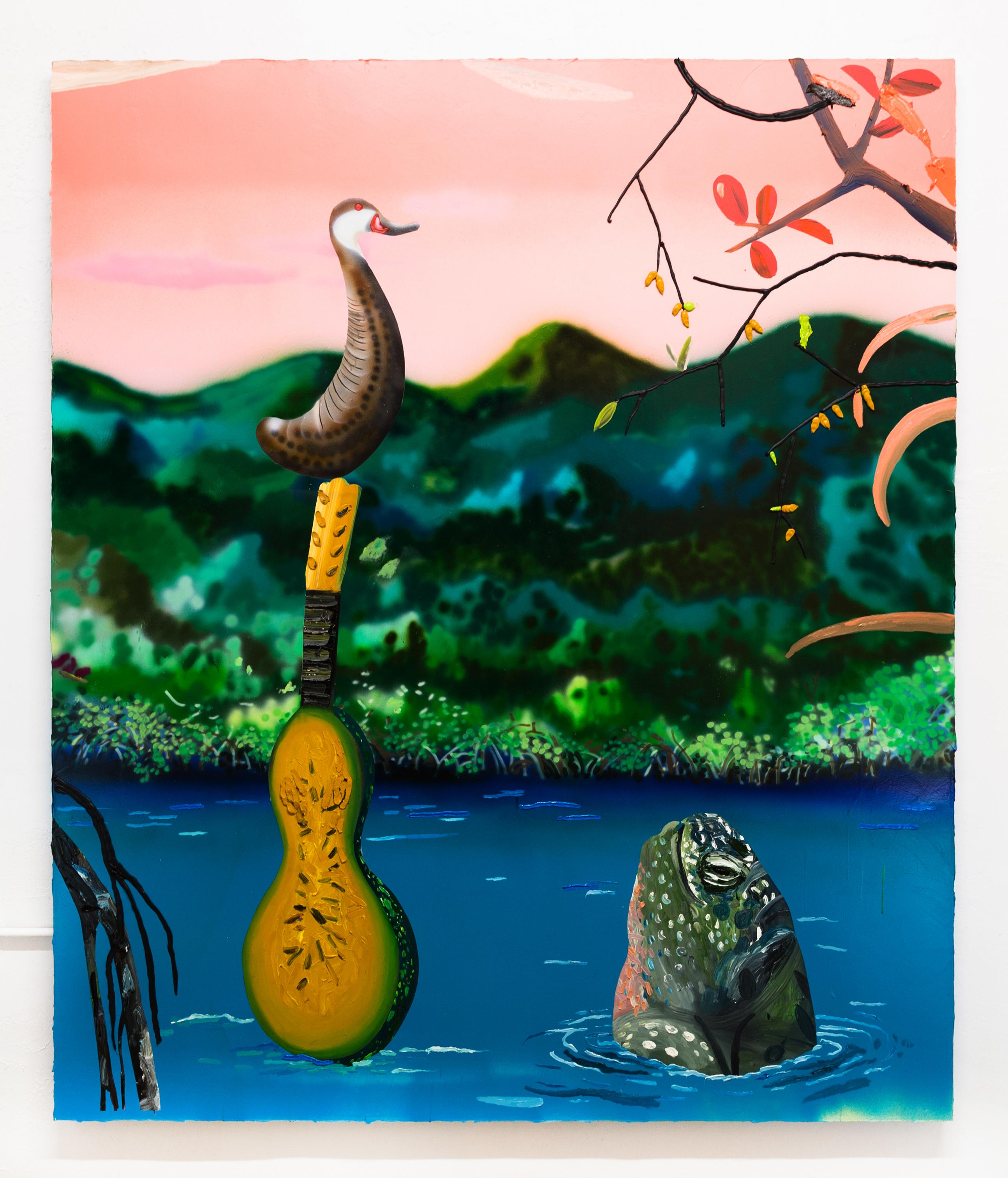

Courtesy of the Instituto de Cultura Puertorriqueña, San JuanIn Caguama(2020, fig. 6), Velázquez uses these learned techniques to compose a dreamlike scene framed by nature in a way that recalls Raquel Rivera's paintingNiebla. Here, acaguama(“giant turtle” in the Taíno language) rises up from the waters to greet a mysterious character: agüiro-bodied duck perched atop a gourd-shaped bordonúa bass guitar. The duck is apato quijada colorada, a white-cheeked pintail migratory duck that seasonally resides on the island from February to May. This scene was inspired by an early morning canoe trip Velázquez took with a friend to the mangroves in Salinas, Puerto Rico, where the artist witnessed the rare sight of a wild leatherback sea turtle, ortinglar. The apparition of the turtle, and the setting more broadly, reminded Velázquez of the paintingPalm Leaf Hat (1991) by Rafael Ferrer, a scene depicting two men on a small boat at sea against the backdrop of a mountainous landscape. Ferrer's stacked figures create a triangular composition to place the viewer inside the boat, in line with the two men. From the boat's deck, one of the men mysteriously returns the viewer's gaze as if in the midst of conversation.

Omar Velázquez, Caguama, 2020. Oil and acrylic on canvas; 72 x 84 in.

Courtesy of the artist and Corbett vs. Dempsey, Chicago. Photo: Julio Lugo Rivas.Caguama, like many other works in Velázquez's oeuvre, holds indications of the artist's obsession with pareidolia, or the tendency to perceive images, faces, or patterns in nature and inanimate objects. Here, it is most visible in the face embedded in the mountains at the right side of the painting's edge, who witnesses the bizarre scene that unfolds on the water's surface. Less visible is the double-sided smiling and sad face of the turtle; a nod, perhaps, to the ancient Greek symbol representing comedy and tragedy. The encounter between the two main characters of the scene—a migratory duck and a sea turtle that carries its home on its back—can be interpreted as a clash of cultures or a collision between temporalities. At once local and foreign, the work claims the landscape as a site of confrontation, but also as a space of memory and history.

The vertical composition of the two figures in Caguama is repeated in Velázquez's painting Maboya (2020), titled after the evil Taíno spirit that sends hurricanes as punishment for bad deeds. Again, the encounter in the painting is between two figures, here, a múcaro real (native owl) perched on a pig's head that is staked on a pole and an African mask from the Baga people of Guinea. The mask, which Velázquez saw in a vitrine at the Museo de Arte de Ponce, represents the fertility goddess Nimba. The múcaro real, a symbol of supernatural activity, is sourced from a childhood memory of a spiritual encounter that has stayed with the artist throughout the years. The references associated with the pig head are multifarious; to Velázquez the head is at once a sacrifice, a reference back to the roasted pig in El velorio, and an implied critique of the role of the police. A delicate spider web extends from the wooden pole into barbed wire, used as a tool in rural areas to demarcate private property and also an allusion to Velázquez's interest in the signs and symbols of heavy-metal music culture. A surgical mask hanging from this barbed wire line brings the painting to the year of its making; one marked by a global pandemic, violent confrontations between police officers and Black citizens, and, in Puerto Rico, by an earthquake and the continued social and economic aftershocks of 2017's Hurricane Maria.

Through violent mechanisms of oppression and control, coloniality—the darker side of modernity—works in insidious ways in postcolonial and neocolonial contexts.13 To see this control, it is not sufficient to rely on our physical vision. It requires a type of sight that transgresses the surface and goes beyond the boundaries of convention. Velázquez's rural scenes, bereft of human figures, and his interest in craft folk forms could be interpreted as nostalgic: a longing for life in Puerto Rico before rapid modernization and urbanization. But something more profound lies beneath the surface. In his paintings, confrontational tension enacts an unfinished and unfolding situation, where narrative symbols do not lead to a linear story and where color is deployed strategically in deceptive ways, the same way that Puerto Rico's tropical landscape tends to hide the dark and complex realities of its colonial history. Ultimately, tropical darkness is not a shade, but a form whose shape is incessantly defined by the dreams and nightmares that keep us awake at night.

Footnotes

- In conversations with the author, Omar Velázquez has mentioned H. C. Westermann, Max Beckmann, Laura Owens, and Matthew Wong as important references in his work.

- Puerto Rico does not have higher education institutions that offer graduate programs in studio art. For that reason, many Puerto Rican artists come to the United States to pursue their graduate degrees.

- Rafael Ferrer showed his work in the group exhibition Sculptors: Extended Structures at the MCA in 1971, presented the work Niche-Chicago also at the MCA the same year, and had a solo exhibition titled Museo (Museum) also at the MCA in 1972. Although based in Philadelphia during the 1970s, his work was represented by Phyllis Kind Gallery in Chicago. This gallery represented the work of artists who later became well known as the Chicago Imagists.

- Deborah Cullen, Rafael Ferrer (Los Angeles, CA: UCLA Chicano Studies Research Center Press, 2012), 82.

- The instrument is modeled after sixteenth-century small guitars brought by Spanish colonists from the Canary Islands that have, for the most part, disappeared from popular culture.

- To learn more about Francisco Oller y Cestero, please see Marimar Benítez. Francisco Oller: Un Realista del Impresionismo. Ponce: Museo de Arte de Ponce, 1983 and Edward J. Sullivan. From San Juan to Paris and Back: Francisco Oller and Caribbean Art in the Era of Impressionism. New Haven: Yale University press, 2014.

- Omar Velázquez, in conversation with the author.

- "The Cuatro's Story: El Proyecto Del Cuatro /The Cuatro Project." The Cuatro's Story | El Proyecto Del Cuatro /The Cuatro Project. Accessed November 5, 2020. cuatro-pr.org/node/83.

- Velázquez's formal language is indebted to the painting practice and research interests of painter and mentor José Luis Vargas, whose research into the history of the supernatural in rural Puerto Rico is the main subject of his work.

- Although Puerto Rico is not a state, it is subjected to the Jones Act, which regulates domestic travel within the United States and requires all goods between US ports to be transported in ships that are built, owned, and operated by US citizens or residents.

- Omar Velázquez, in conversation with the author.

- Omar Velázquez, in email exchange with the author. November 2, 2020.

- Walter Mignolo, The Darker Side of Western Modernity: Global Futures, Decolonial Options (Durham: Duke University Press, 2011).

CREDITS

This digital brochure was published on the occasion of the exhibition Chicago Works: Omar Velázquez, organized by Carla Acevedo-Yates, Marilyn and Larry Fields Curator, with Iris Colburn, Curatorial Assistant, and presented from , to , in the Sternberg and Rabin galleries on the museum's third floor.

- Funding

- Generous support is provided by Nancy and David Frej, Ashlee Jacob, and the Sandra and Jack Guthman Chicago Works Exhibition Fund.

- With thanks to our colleague institution, the National Museum of Puerto Rican Arts and Culture.

- DIRECTOR of CONTENT STRATEGY

- Kelsey Campbell-Dollaghan

- MANAGER of RIGHTS and IMAGES

- Elyssa Lange

- EDITOR

- Leah Froats

- MARILYN AND LARRY FIELDS CURATOR

- Carla Acevedo-Yates

- PROOFREADER

- Tyler Laminack

- DESIGN and PROGRAMMING

- Alexander Shoup

The Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago is a nonprofit, tax-exempt organization accredited by the American Alliance of Museums. The museum is generously supported by its Board of Trustees; individual and corporate members; private and corporate foundations, including the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation; and government agencies. Programming is partially supported by a grant from the Illinois Arts Council Agency.

Free admission for 18 and under is generously provided by Liz and Eric Lefkofsky.

The MCA is a proud member of Museums in the Park and receives major support from the Chicago Park District.

© 2021 by the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means including photocopy, recording, or any other information-storage-and-retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher.

Images found on this site are for educational use and are published under the umbrella of the Fair Use doctrine.