Fragments of a Crucifixion

This website was built on the occasion of the exhibition Fragments of a Crucifixion at the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago, May 25–November 3, 2019, organized by Marjorie Susman Curatorial Fellow Chanon Kenji Praepipatmongkol and presented in the McCormick Tribune Orientation Gallery on the museum's second floor. It brings together new scholarship exploring the themes of the exhibition.

Introduction: The Medium of the Cross

Chanon Kenji Praepipatmongkol

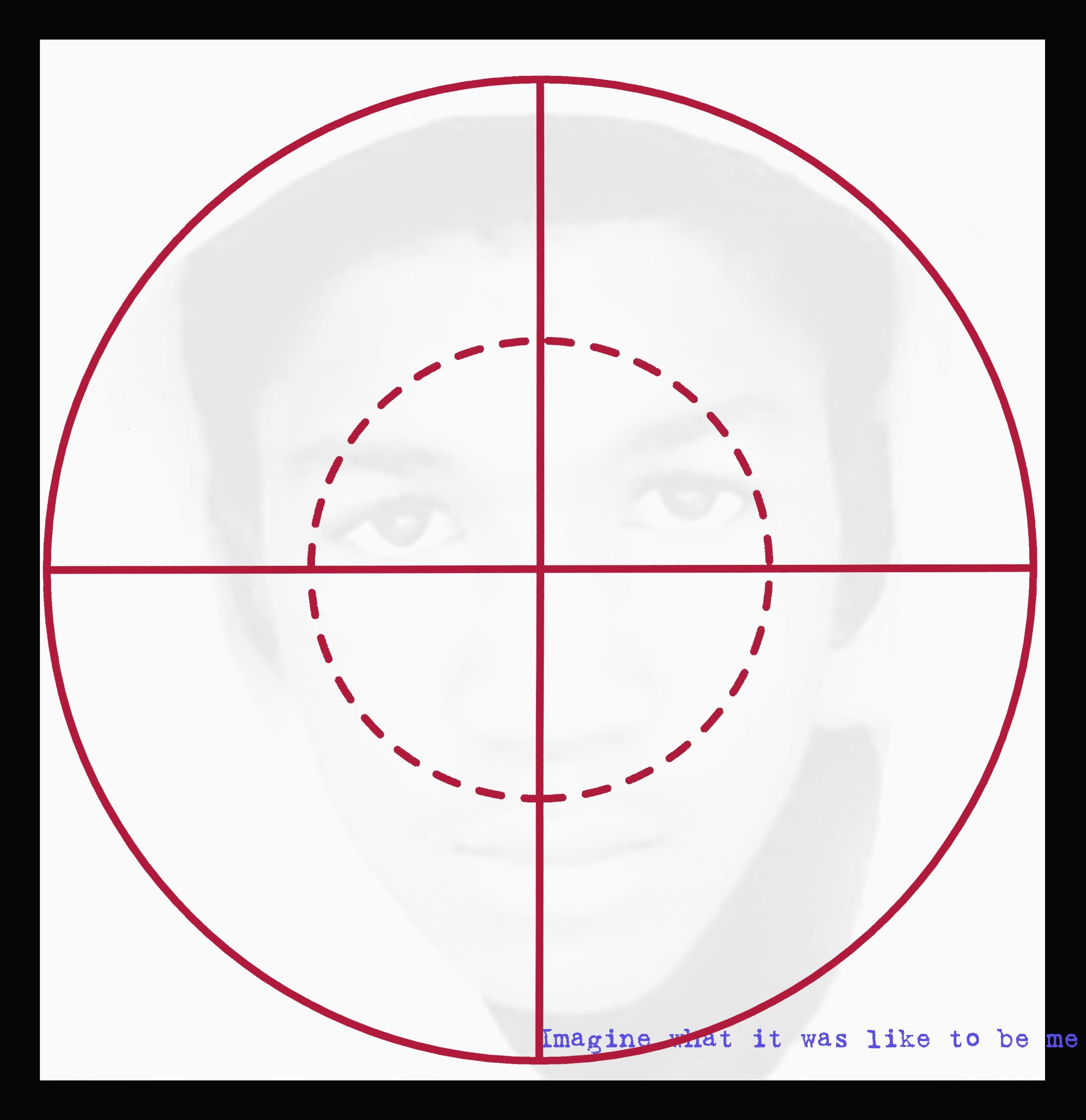

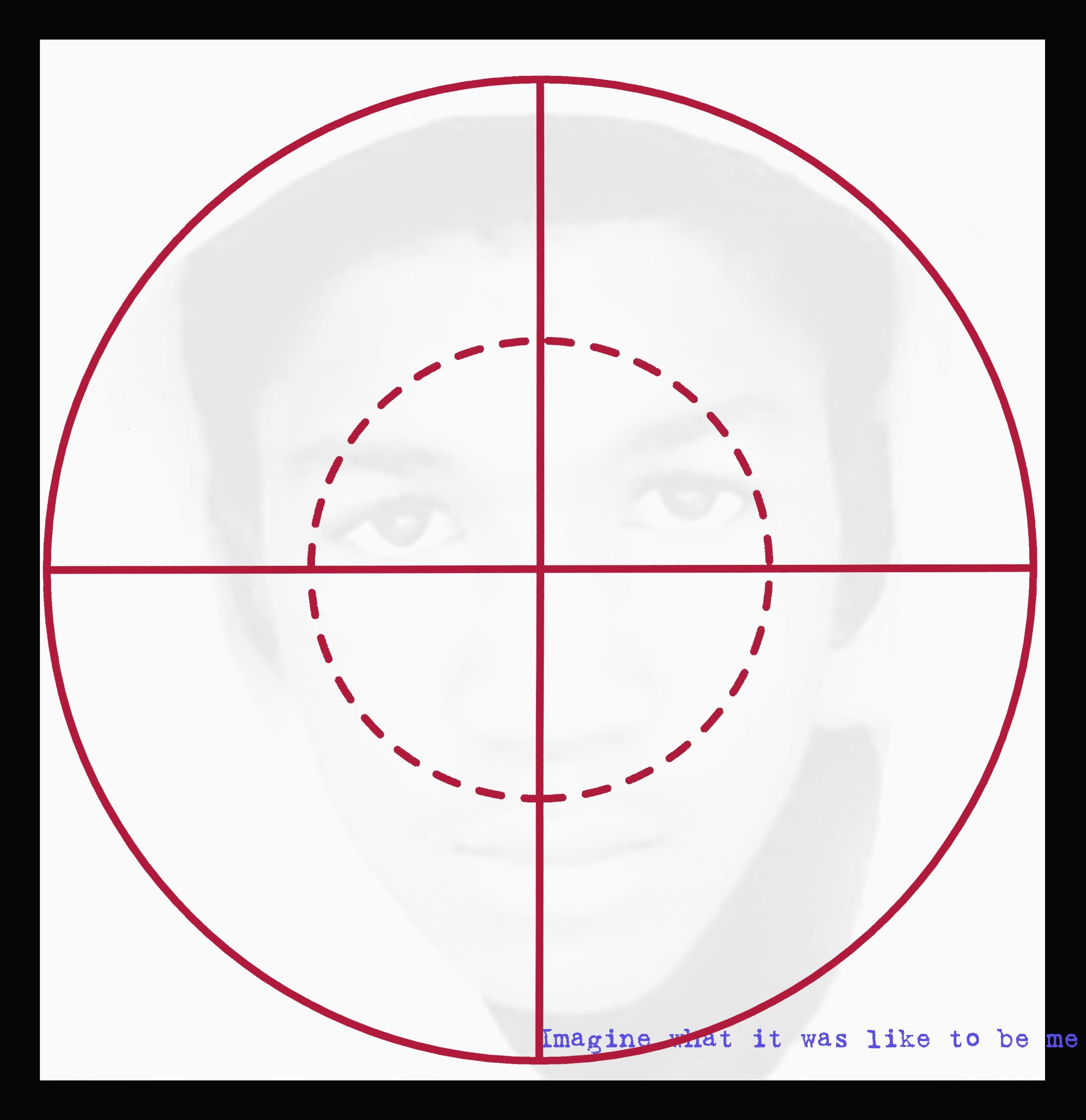

First, consider the crosshairs. Consider this contemporary sign of the cross that unremittingly frames black lives in the United States.

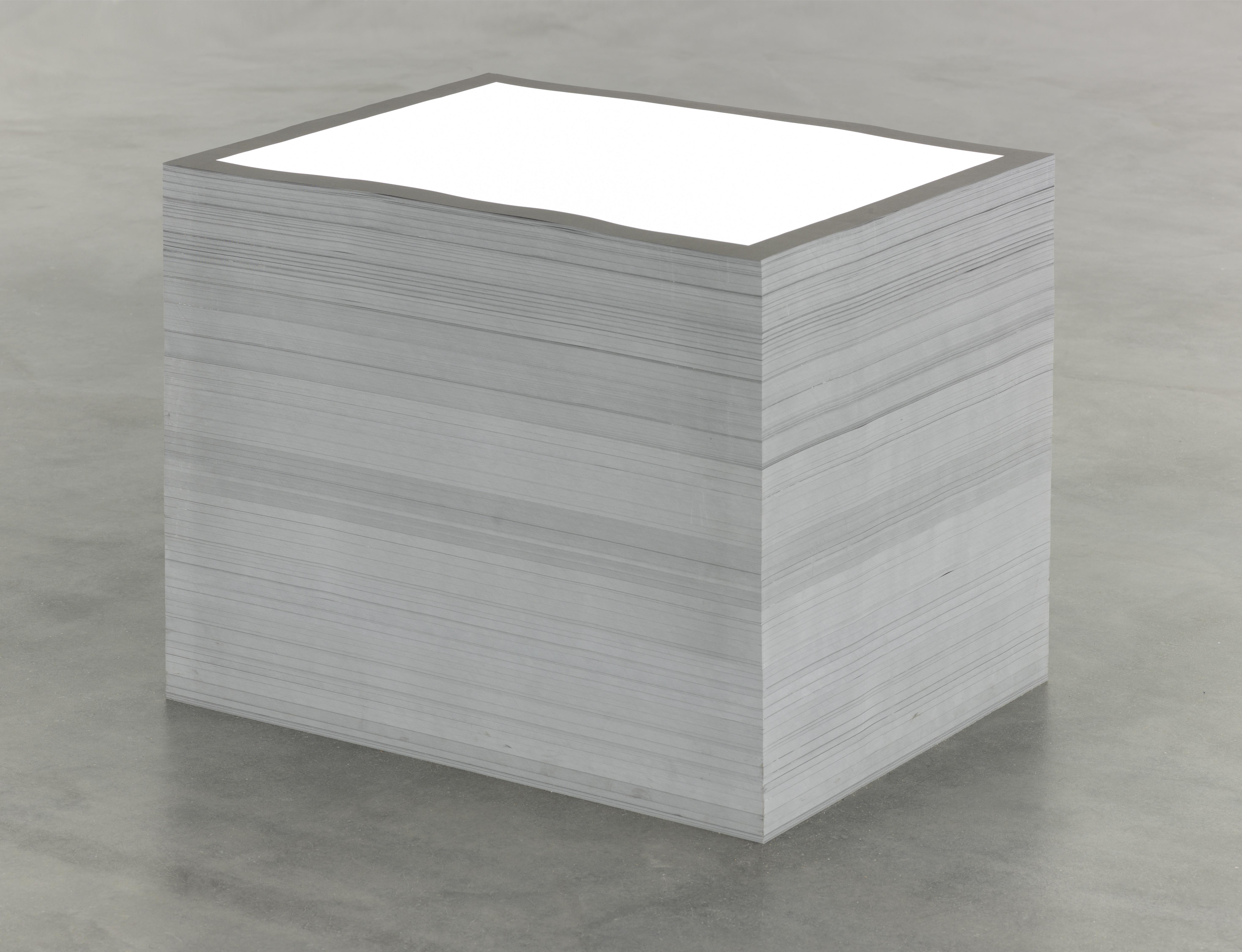

Adrian Piper, Imagine [Trayvon Martin], 2013. Digital PNG formatted image; 10 4/5 × 10 2/5 in. (27.3 × 26.5 cm), 300 dpi. Asset available for free here.

Collection of the Adrian Piper Research Archive Foundation Berlin © Adrian Piper Research Archive Foundation BerlinThen, consider Imagine [Trayvon Martin] provokes intense reactions, particularly from those who feel implicated by its message: “Imagine what it was like to be me.”

What is so striking about the work's demand on viewers is that it forces self-identification in stark terms. “For some,” Larissa Pham writes, “it's all too easy to imagine what it would like to be Trayvon; for others, it's a forced self-examination, a posthumous exercise in empathy.”1 James Hannaham goes further, pronouncing that the work “seemed directed toward people who don't spend as much time identifying with Trayvon Martin as I do.”2 To Nico Wheadon, Piper seems cruel in making this “injurious provocation,” when just beyond the museum awaits, in her words, the precarious reality of my very black, American life.

3

But Piper is more than a producer of mnemonic devices and empathic tools. For decades she has exploited the uneasy distance between the privileged world of institutionalized art and the social reality of black lives outside its walls.4 Perhaps this is what the artist wants viewers to do: to mind the interval between the frames. While Martin's visage initially appears as the singular target of attention, a longer look reveals that things are slightly askew. Piper placed the crosshairs off-center, with the four cardinal points set at asymmetric and unequal intervals to the border. It is this black band around the edge of the image that provides a sense of space and a measure of distance—that implies there exists a vantage point outside the circumscribed view of the police's crosshairs. The black border holds space for a perspective in which whiteness is neither the center nor the frame.5

Fragments of a Crucifixion attempts to make room for another perspective, one that displaces the view through the crosshairs with a consideration of life and death through a religious lens. We need not look far for signs of faith. No one was as vocal about the spiritual significance of Martin's life and death as his mother, Sybrina Fulton.6 Over the course of Zimmerman's highly publicized trial in 2013, Fulton shared her Christian testimony with the world every day, as she tweeted prayers and passages from the Bible alongside photos of her child. On day 12 she wrote, “When Christ is the center of your focus, all else will come into proper perspective.”7 For Fulton, it is through the intermediary sign of Jesus's cross that Christianity's most gripping promise is born: that violence can be changed by faith into suffering that is not in vain.

In bringing voices of faith to bear on artworks, Fragments of a Crucifixion proposes that contemporary art is not so secular a realm that religious and spiritual narratives cannot penetrate it. Centered on works in the MCA's collection, the exhibition gathers a number of works that may appear to have more to do with race than religion. But the exhibition's interpretive materials—whether wall labels, public programs, or this publication—aim to reveal the often-invisible religious and spiritual currents that animate these works of art. Doing so connects contemporary artists in the show to a long line of artists who have used the crucifixion as a powerful symbol to address the experience of racial violence in the United States.8 The exhibition explores the continuing relevance of the sign of the cross, for it is through this sign that contemporary artworks might come into focus as icons, emblems, and relics of public mourning today.

The idea for a digital publication to accompany the exhibition grew out of a desire to engage the heterodox language of faith that pervades recent responses to the violence inflicted on black people in this country. Since 2013, activists associated with the Black Lives Matter (BLM) movement have shared texts, images, and symbols drawn from multiple faiths to hold a space of remembrance for those murdered, and to reclaim the sacredness of lost lives.9 But in a departure from the rhetoric of the Civil Rights era, many of BLM's most visible figures have presented the movement's religious orientation as part of a broader set of queer and indigenous commitments.10 This collection of essays was conceived in this spirit of inclusivity and intersectionality, with the hope of fostering public discussions around religion and race that are not defined by already-given subject positions (e.g., black versus non-black, Christian versus non-Christian).

The publication brings together artists and scholars committed to exploring the relationship between art, spirituality, and social justice. It features inquiries at once deeply personal and critical, and which traverse the terrain of art history, theology, moral philosophy, queer theory, and performance studies. Xiao Situ argues for the potential of contemporary art to make visible “what Christ's activity might look like in the present day.” She uncovers in Titus Kaphar's Ascension (2016) a resonance between the image of crucifixion, the legacy of lynching in America, and recent protests by athletes against police brutality. Phoebe Wolfskill’s conversation with artist Joyce J. Scott explores Scott's often sardonic yet deeply religious approach to figuring black bodies—an approach that imbues histories of racial violence with unexpected levity and spiritual hopefulness. My interview with Paul Pfeiffer addresses the strange temporal loops and disjointed Biblical narratives in his video works as elements of an aesthetic that complicates the desire for resolution. Anni Pullagura and Josh Chambers-Letson present approaches to history that refuse the inevitability of origins and endings. They offer meditations on art's capacity to hold space for the wayward passing of time—the delays, suspensions, and projections that allow for life to continue.

These authors place the matter of faith at the center of their discussions, yet elude clear distinctions between the religious and the secular. The compelling question then becomes not what set of beliefs we subscribe to, but rather why, how, and when we choose to believe that one interpretive frame edges out or invalidates another.

Footnotes

- Larissa Pham, “This MoMA Show Asks You to Confront Racism—Both in Strangers and Yourself”, Garage Magazine, April 3, 2018.

- James Hannaham, “Adrian Piper”, 4Columns, May 4, 2018.

- Nico Wheadon, “Adrian Piper: From Passing to Purple,” Brooklyn Rail, May 1, 2018.

- For resources on Piper's artistic practice and career, see Adrian Piper: A Synthesis of Intuitions, 1965–2016 (New York: Museum of Modern Art, 2018) and Adrian Piper: A Reader (New York: Museum of Modern Art, 2018).

- On “holding space” through art, see Helen Molesworth, “Art is Medicine,” Artforum 56, no. 7 (March 2018).

- Elizabeth Dias, “The Christian Witness of Trayvon’s Mother,” Time, July 15, 2013.

- Sybina Fulton, Twitter, June 25, 2013, 11:02 am, twitter.com/sybrinafulton/status/349543220730015744.

- See James Romaine and Phoebe Wolfskill, eds., Beholding Christ and Christianity in African American Art (University Park: The Pennsylvania State University Press, 2017); Edward J. Blum and Paul Harvey, The Color of Christ: The Son of God and the Saga of Race in America (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2012); and James Treat, Around the Sacred Fire: Native Religious Activism in the Red Power Era (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2003).

- Vincent Lloyd, ed., “Religion, Secularism, and Black Lives Matter,” The Immanent Frame, September 22, 2016.

- Josef Sorett, “A Fantastic Church? Literature, Politics, and the Afterlives of Afro-Protestantism,” Public Culture 29, no. 1 (2017): 17–26.

Titus Kaphar's Ascension and Colin Kaepernick's Kneel

Xiao Situ

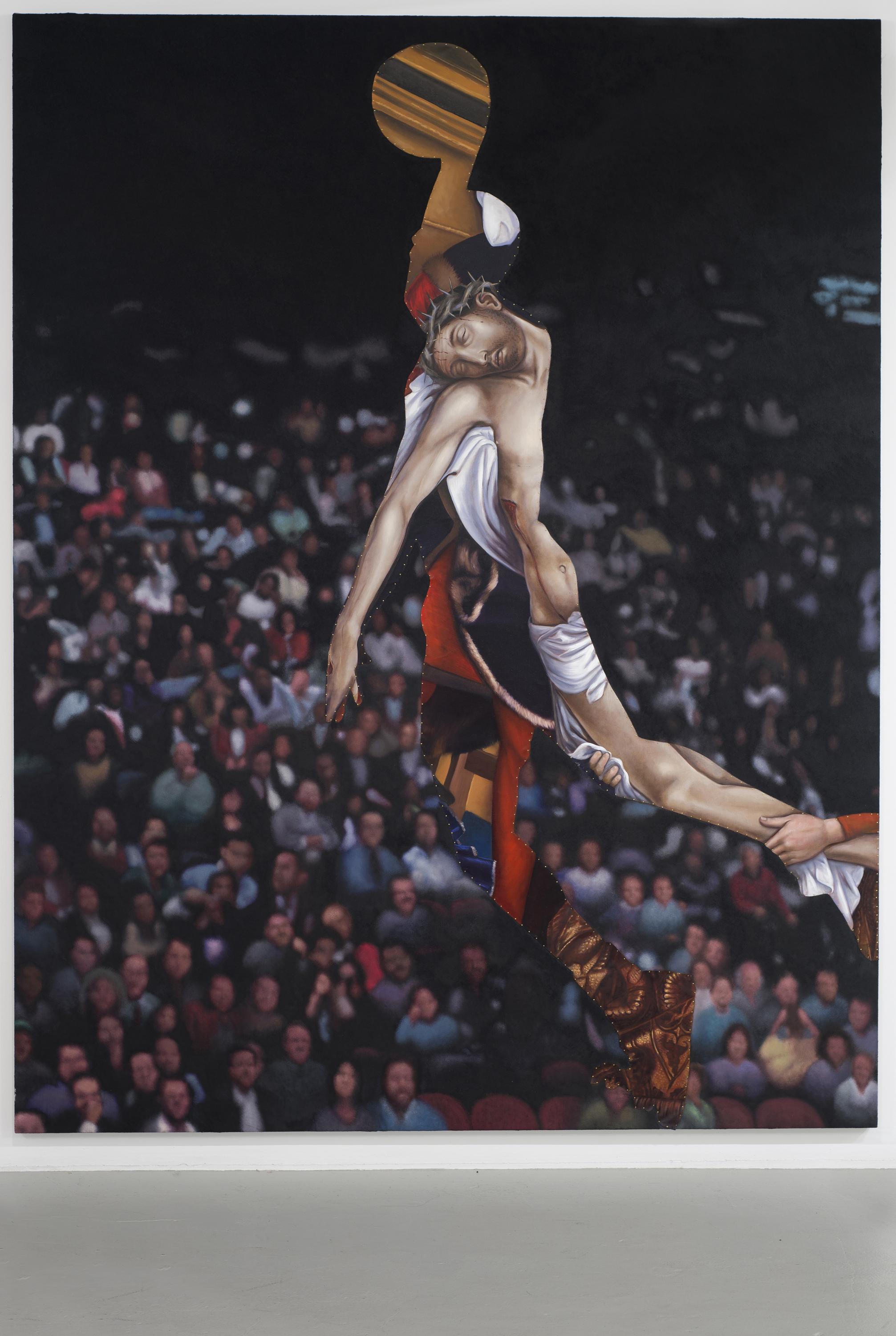

Ascension(2016) by Titus Kaphar (b. 1976) is a larger-than-life-size painting that articulates a basketball player's leap into the air before a crowd of spectators. At the same time—and perhaps jarringly—it also depicts a crucifixion and a lynching. It can take a few minutes to survey in this single work these three distinct scenarios: the outlines of the basketball player's body mid-dunk, the suffering of Christ on the cross, and the emergent form of a person being lynched.

Titus Kaphar, Ascension, 2016. Oil on canvas with brass nails. 108 x 84 x 1 ½ in. Collection of Laura Lee Brown and Steve Wilson, 21c Museum Hotel.

Image courtesy of the artistI am compelled to reflect on Kaphar's Ascension because it sheds light on a phenomenon that has profoundly affected the way I think about kneeling. Colin Kaepernick (b. 1987), the former quarterback for the National Football League's San Francisco 49ers, began kneeling instead of standing during the national anthem in the fall of 2016. He cited systemic racism and police brutality against minorities as the catalyst for this act of protest. As he continued to kneel at games, and as other collegiate and professional athletes joined him, a national debate ignited over race, sports, and politics.

Kaepernick's kneel was, to me, a deeply spiritual move. When I saw images of him kneeling, I instinctively thought about prayer, mourning, respect, and vulnerability. I was reminded of Jesus washing his disciples' feet as recounted in the Gospel of John, and of the many times the Psalmist sings of bowing down before God. As someone with a chronic illness that makes mobility slow and challenging, I am by necessity very economical and deliberate with my own gestures, and I frequently reflect on the symbolic meanings of even the most mundane movements. Kaepernick's kneeling therefore captured my attention. As an art historian, as the sufferer of a chronic illness, and as a person with spiritual and religious inclinations, I discuss here how Kaphar's Ascension situates Kaepernick's kneel in a broader spiritual, cultural, and historical context.

Kaphar's Ascension is an explicitly religious painting. The title not only describes the upward trajectory of the basketball player's body as he rises through the air, but also references, by way of opposing correspondence, the downward movement of Christ's body lifted off the cross after his crucifixion. In fact, the image of Christ that appears in the interior of the basketball player's silhouette is a painted quotation of Rogier van der Weyden's 1435 Descent from the Cross, one of the most famous depictions of the crucified Christ in Western art. Kaphar thus brings together two bodies and two opposing forces in one human figure. Jesus's pale right arm and right leg slip into the contours of the basketball player's left arm and left leg; Jesus's downward-tilting head rests beneath the basketball player's upward-looking profile. The artist yokes the two bodies together through pictorial, material, and performative means: by employing brass nails to anchor van der Weyden's Christ to the athlete's form, Kaphar at once recalls and evokes the act of Jesus's crucifixion and the nails used to pin him to the cross.

Situ Figure 2 and Figure 3

Rogier van der Weyden, The Descent from the Cross, before 1443. Oil on panel; 204.5 × 261.5 cm.

PLACEHOLDER © Museo Nacional del Prado

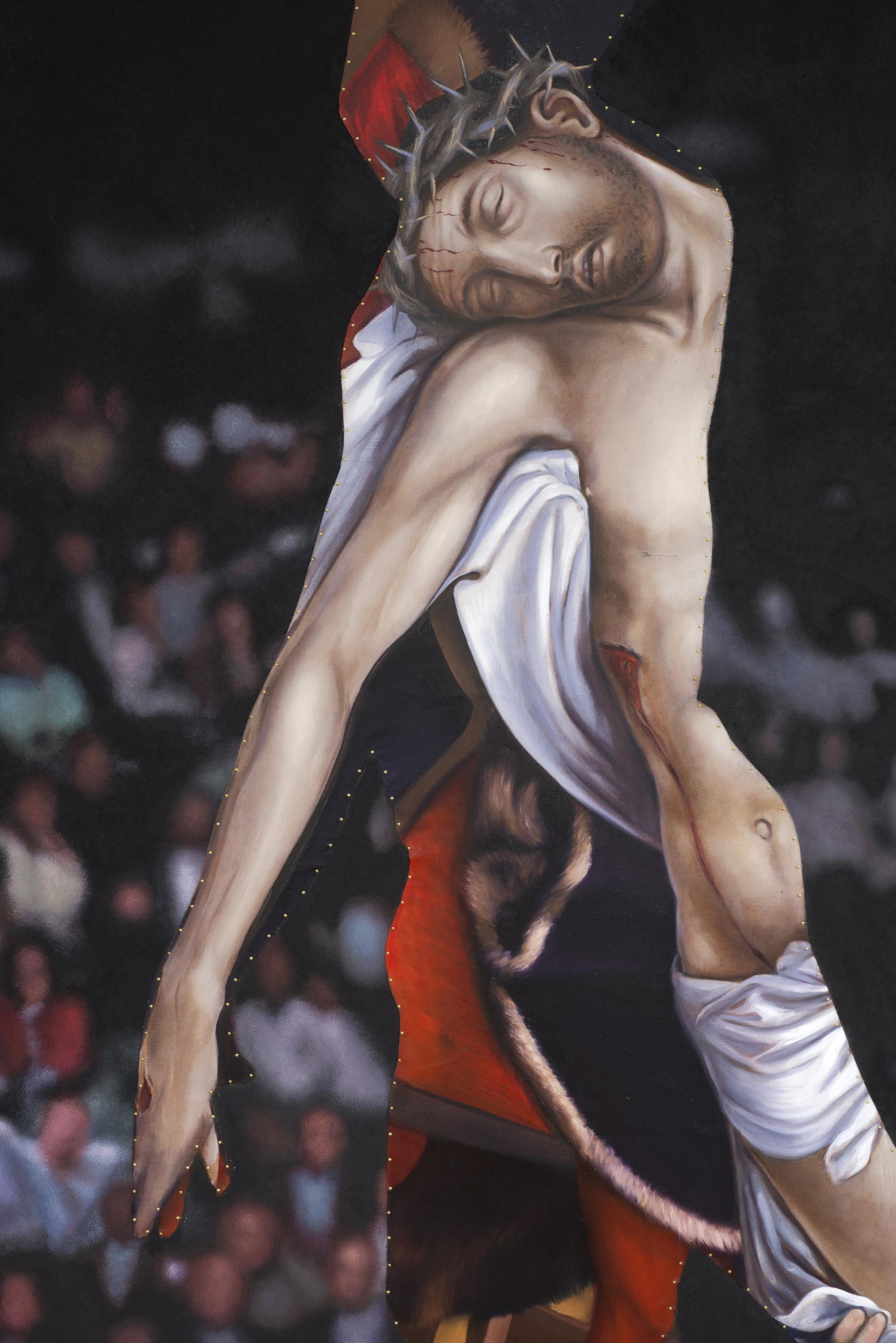

Titus Kaphar, Ascension (detail), 2016.

Image courtesy of the artistThe silhouette comprises not only Christ and the basketball player, however, but also a third human form—that of a person being lynched. Christ’s crown of thorns encircles the basketball player’s neck as though a spiky noose. Red fabric from van der Weyden’s painting becomes a thick trail of downward-flowing blood. The athlete’s lifted right arm doubles as the taut vertical of a hangman’s knot. Simultaneously pulled up into the air and weighed down by his own body, the lynching victim suffers the forces of both ascension and descent.

There are haunting similarities between Christ's crucifixion and the lynching of black people in the United States. In his 2011 book The Cross and the Lynching Tree, theologian James H. Cone reflects:

The cross and the lynching tree are separated by nearly 2,000 years. One is the universal symbol of Christian faith; the other is the quintessential symbol of black oppression in America. Though both are symbols of death, one represents a message of hope and salvation, while the other signifies the negation of that message by white supremacy. Despite the obvious similarities between Jesus' death on a cross and the death of thousands of black men and women strung up to die on a lamppost or tree, relatively few people, apart from black poets, novelists, and other reality-seeing artists, have explored the symbolic connections.1

Kaphar is active as one of Cone's reality-seeing artists. Ascension’s merging of three figures in one invites echoes of the doctrine of the Trinity, calibrating the experience and value of each figure to a point of equality and mutual empathy with the other two. The basketball player, the crucified Christ, and the lynching victim share in each other's suffering and victory. By featuring van der Weyden's Christ in particular—which is a very white, Eurocentric-looking Jesus—Kaphar's painting challenges the ubiquity of this portrayal of Jesus in Western art and confronts assumptions about both where and with whom Jesus's identification and compassion lies. Kaphar has touched upon the presumed whiteness of Jesus in previous paintings, most notably in Holy Absence I (2012) and Holy Absence II (2014). The appearance of Christ in Ascension, however, frames the athlete's and the lynching victim's experience in a particularized black Christological narrative.

In religious studies, Christology is the branch of theology that examines the person and nature of Christ as he is depicted in the canonical Gospels. Black Christology, in particular, probes how Jesus's life, suffering, and resurrection speak to the specific historical contexts, lived experiences, and ontological concerns of black persons and their communities. Following this line of theological analysis, Christ's blackness is defined by his identification with and concern for black persons' bodies, minds, and souls—not only with regard to historical and ongoing suffering and oppression, but also in terms of traditions and expressions of joy, resilience, and aspiration toward existential and spiritual liberation. The Jesus of black Christology is a Jesus born into a poor, marginalized, and oppressed minority group under the rule of the Roman Empire. Jesus's care and ministry among the most vulnerable and neglected individuals in society earned him scorn, rebuke, and ultimately public execution from state authorities. The movement he instigated emerged out of a spirit of protest, calling for unconditional love and redemptive justice for the poorest and most powerless peoples in first-century Palestine.2

While the connection between crucifixion and lynching may therefore seem apparent in Kaphar’s painting, the basketball player’s relationship to these two figures may seem somewhat more oblique. First, I need to address my own assumption of the basketball player’s blackness. By presupposing the racial identity of Kaphar’s athlete, I am admittedly participating in racial profiling. The basketball player’s very form invites the potential for precisely this mechanism of generalization in that it is literally a profile—a silhouette comprised of outlines and contours. Nothing in the silhouette’s interior explicitly indicates the figure’s racial or ethnic identity, and yet my association between this particular physical stance and black athleticism in basketball has been powerfully shaped by popular visual discourse and the cultural perpetuation of stereotypes. More specifically, the shape of the basketball player’s body is strikingly reminiscent of the image of the Jumpman, Nike’s logo for the Air Jordan brand of sneakers and sportswear inspired by basketball legend Michael Jordan (b. 1963). For me, the correspondence between the iconic Jumpman logo and Jordan’s legacy as a paradigm of black athletic virtuosity is so ingrained that it invariably operates in Kaphar’s painting.

So what, then, is the relationship among this athlete and Christ and the lynching figure? In van der Weyden’s original painting, a man dressed in black and gold gently holds Jesus’s legs aloft as this man and others carry him down. In Kaphar’s canvas, however, these same two hands have the appearance of grabbing onto the athlete’s legs and dragging his body down. Considered through the context of history, this gesture might point toward the legacy of slavery and the forms of systemic racial oppression that emerged after Emancipation, when arbiters of white culture continued to exploit the emancipated black population as sources of labor, entertainment, and economic revenue by maintaining positions of power and influence in the institutions that oversaw and leveraged the productivity and performance of black bodies.

In his landmark 1969 book The Revolt of the Black Athlete, sociologist, former athlete, and civil rights activist Harry Edwards asserted that systemic racism has been built into the very heart of American collegiate and professional sports. The emergence of black athletics after Emancipation was an extension of black exploitation and commodification—especially that of bodily labor over intellectual pursuit. “From the perspective of many white coaches and athletic directors,” Edwards observed, “the world does not need black doctors, sociologists, chemists, dentists, mathematicians, computer operators, or biologists.”3 White cultural prioritization of the black body over the black mind—and indeed, over black wholeness in general—extends to the athlete's voicing of care and concern about the rights and wellness of black communities: “Whites may grudgingly admit a black man's prowess as an athlete, but will not acknowledge his equality as a human being.”4

Edwards published The Revolt of the Black Athlete one year after sprinters Tommie Smith and John Carlos raised the Black Power salute during the US national anthem at the Olympics awards ceremony in Mexico City. Smith and Carlos raised their arms to protest the racism and injustice that they witnessed and experienced as black citizens in the United States. For their display of activism, Smith and Carlos received significant ostracism and career retribution from the US sports establishment in the years that followed. Like Jack Johnson, Paul Robeson, Jackie Robinson, Muhammad Ali, and many other black athletes who were politically outspoken, Smith and Carlos paid a steep price for publicly voicing their discontents.5

Kaphar's Ascension seems to suggest that despite the fame, adulation, and financial reward black athletes may enjoy, institutional white hands still maintain a grip on their ankles. The silhouette of the basketball player contains within its interior the shadows of lynching and the suffering of Christ, and the athlete's ascension is thus a compromised transcendence: any adoration and payment he receives might come at the price of certain other sacrifices that stem ontological wholeness and full humanity. (This athlete is, after all, shown in part and not in whole, appearing as a silhouette in profile rather than a fully depicted figure with specific, particularized, or individualized features.) In contemporary sports writing, the term “greenwashing” describes the suppression or silencing of an athlete's black identity while idolizing their talent and profitability. While “greenwashing” is a term employed in the sectors of economics and environmentalism to describe the marketing of environmentally sustainable products and practices, in the context of racial politics in sports the word refers to the racial or cultural erasure that can occur when a sports authority or sponsoring company discourages a black athlete's expression of black identity.6 Although a predominantly white sports establishment and media might praise a black athlete for his physical performance, sports or team authorities might try to regulate or downplay his expressions of allegiance to or identification with black culture, heritage, or politics. In this light, the basketball player's silhouette in Ascension differs from the Air Jordan Jumpman logo in one detail affecting full freedom of movement: while the Jumpman's legs are splayed wide open to form an exuberant upside-down V, the two white hands grasping the left leg of Kaphar's athlete seem to force his knees to bend uncomfortably.

Situ Figure 4

Titus Kaphar, Ascension (detail), 2016. Oil on canvas with brass nails; 108 × 84 × 1 1/2 in. Collection of Laura Lee Brown and Steve Wilson, 21c Museum Hotels.

Image courtesy of the artistWhen Colin Kaepernick began bending his left leg in order to kneel during the national anthem, his gesture seemed to bear a Christological dynamics of ascension and descent—a Gospel physics of crucifixion and resurrection. “I am not going to stand up to show pride in a flag for a country that oppresses black people and people of color,” Kaepernick said: “To me, this is bigger than football and it would be selfish on my part to look the other way. There are bodies in the street and people getting paid leave and getting away with murder.”7 Kaepernick was referring to the many black lives that were cut short by fatal police shootings in recent years: Trayvon Martin, Tamir Rice, Jordan Davis, Rekia Boyd, Michael Brown, and too many others. As author and NBA veteran Etan Thomas discusses in his interviews with NFL and NBA professionals, many athletes were deeply and personally affected whenever _another_ police shooting had taken a black life or _another_ police officer was acquitted after firing shots.8 For some, these events reminded them of their own youthful experiences of being profiled or violently handled by members of law enforcement. For others, these fatalities provoked concerns for their own children who might be vulnerable to such treatment. For many of those whom Thomas interviewed, such incidents of police brutality forced them to reckon with the centuries of insidious anti-black sentiment that has shaped American institutional systems to criminalize black bodies. Although some of them wanted to address these racist systems through the platform of their high visibility as professional athletes, they were also concerned about possible career retributions should they voice their concerns or take actions of protest.

While many fans and observers who supported Kaepernick began kneeling, there were others who exerted a strong backlash. “Shut up and play!” became as fervent a mantra as “I'm with Kap.”9 Regardless of the divided opinions among the American public, Kaepernick ultimately paid a heavy professional price for his continued activism. In the seasons following the end of his term with the San Francisco 49ers, not a single NFL team hired him despite his status as one of the best quarterbacks in the league. Whether or not NFL owners intentionally coordinated this effort, it was clear that the league had effectively shut Kaepernick out of professional football.

For protesting against systemic racial injustice, Kaepernick risked his career as a professional athlete. While he filed a grievance asserting that the NFL owners had colluded to shut him out of the league due to his protests, Kaepernick also leaned more deeply and purposefully into his work as an activist. He began wearing shirts that listed the names of victims of fatal police brutality. This act of visual and performative aesthetics of resurrection uses his living body to memorialize the once-living bodies of the victims. People who see the victims' names on the shirts may then say their names, learn about how they lived and died, and bring into communal consciousness their memories. This activism of remembrance and memorialization enacts what some Christian liturgists might call “anamnesis.” Anamnesis is the Greek word for remembrance or memorial. In liturgy, anamnesis usually describes what happens during the Eucharist or communion, when bread and wine are blessed and administered as an act of remembering Jesus's last words and actions at the Passover feast now commonly known as the Last Supper: “Here, eat, this is my body; here, drink, this is my blood. Do this in remembrance of me.” Anamnesis occurs when the eating and drinking are done and remembrance is made. Theologian M. Shawn Copeland expands this characterization of anamnesis in her 2010 book Enfleshing Freedom: Body, Race, and Being, describing anamnesis as the intentional remembering of the dead. It obliges those who inherit the stories of the victims to do what they can to end oppression in the present. It forges solidarity among people and affirms the interconnectedness between humanity and Christ.10

Kaepernick has made his works of activism intensely communal, focusing on solidarity and remembrance. He founded, organizes, and participates in the Know Your Rights Camp for young people: a teaching program adapted from a series of seminars designed by the Black Panther Party for Self-Defense in the 1960s. Although Kaepernick is known for being disarmingly quiet and soft-spoken, he regularly addresses his concerns about social justice issues in ways that draw exponential attention and action.11 Kaepernick is, in effect, reshaping his public identity and personal purpose from athlete to activist, offering a transformed icon for his followers.

Kaepernick's openness to embracing this new role as an activist is critical. His post-NFL identity is one of the most Christological aspects of his story, and many aspects about his biography bear well under the pressures of a Christological narrative. Tattooed on his arms are Psalm 18:39 (“You armed me with strength for battle; you made my adversaries bow at my feet”) and Psalm 27:3 (“Though an army besiege me, my heart will not fear though war break out against me, even then I will be confident”).12 In an interview recorded for the Daily Sparks Tribune in 2013, Kaepernick credited his faith for helping him through challenges he faced throughout his football career:

I'd ask God what his plans are for me. What is God trying to do with me right now? For me, there were times where I'd wonder if I was in the right place and in the right situation, and you have to fall back on God in situations like that and trust him and know that his plan is perfect for you. . . . I think God guides me through every day and helps me take the right steps.13

This quote suggests that, for Kaepernick, his kneel may have felt like a matter of not only being in the right place and situation, but also intuiting that he was the right one to do it. In American football, “taking a knee” describes a technical strategy. During the last few seconds of a game, the winning team's quarterback can kneel while cradling the ball until the play clock runs out. This move effectively halts further action that would unnecessarily disadvantage the winning team. While other players can also kneel at various moments throughout a game, “taking a knee” is so closely associated with the quarterback that the move has come to be known as the “quarterback kneel.”14 Considering his position as quarterback, it seems appropriate—perhaps even fateful—that Kaepernick adopted kneeling as his form of protest. His kneeling was an extension, or rather, _transformation_, of a key move in his repertoire as a quarterback.15

Just as Kaphar's art often collapses different periods in time to show more visibly the full nature of particular events and circumstances, Kaepernick's story offers a chance to see what Christ's activity might look like in the present day, as well as the places where Christ might reside and the people for whom Christ might work. In Cone's landmark 1975 book on black Christology, the theologian points out the importance of holding together Jesus's wasness and isness: “Truth is more than the retelling of the biblical story. Truth is the divine happening that invades our contemporary situation, revealing the meaning of the past for the present.”16 Cone furthermore describes Jesus as one “whom me meet in our social existence,” and that for Christians, “our interest in Jesus' past cannot be separated from one's encounter with his presence in our contemporary existence.”17 Theologian Kelly Brown Douglas adds an even more topical meaning to black Christology, singling out contemporary activism as perhaps the most inclusive and enduring embodiment of Christ's activity today: “Christ can be incarnate wherever there is a movement to sustain and liberate oppressed people.”18 This does not necessarily mean that Kaepernick is a new Jesus or like Jesus, but rather that the movement he initiated by kneeling carries the flicker and flow of the spirit—and that flow is where Jesus and God reside. Jesus abides in and rides on the dynamism of the downward and upward movement that occurs when people kneel; it takes many people moving together to body forth the spirit of God.

Along the lines of black Christological thought, recent events have unfolded such that the circumstances and activities of Kaepernick's isness are suffused with Christ's wasness. Kaepernick's movement of generating care and concern for black lives honors Christ's incarnation in each body and soul. For an artist like Kaphar who is fluent at juxtaposing time periods, suturing together wasness and isness, and engaging the past by scrutinizing the present in his art, the Christological nature of black athletes' stories is something to be surfaced in works like Ascension. The realm of sports is not so secular or contemporary that history's shadows and religious narratives cannot penetrate it. By compressing Michael Jordan's Jumpman and a lynching victim with van der Weyden's Christ—and beyond that, by bodying forth this Trinitarian portrait in the age of Kaepernick—Kaphar reveals why and how a simple act such as bending one's knee might, in Kaepernick's words, be “bigger than football.” Bending one's knee is about insisting on the uncompromising worth of black lives—not as sources of labor, economic gain, or cultural consumption, but as fully human and fully divine incarnations of God's ceaseless love and creativity.

Footnotes

- James H. Cone, The Cross and the Lynching Tree (Maryknoll, New York: Orbis, 2011), xiii.

- For introductions to black Christology, see James H. Cone, Black Theology and Black Power (Maryknoll, New York: Orbis, 1997); James H. Cone, The Cross and the Lynching Tree (Maryknoll, New York: Orbis, 2011); Kelly Brown Douglas, The Black Christ (Maryknoll, New York: Orbis, 1994); and Kelly Brown Douglas, Stand Your Ground: Black Bodies and the Justice of God (Maryknoll, New York: Orbis, 2015).

- Harry Edwards, The Revolt of the Black Athlete, rev. ed. (1969; repr., Champaign, IL: University of Illinois Press, 2017), 17.

- Edwards, Revolt, 6. For discussions about white cultural prioritization of the black body over the black mind in the history sports and education reform, see Howard Bryant, The Heritage: Black Athletes, a Divided America, and the Politics of Patriotism (Boston: Beacon Press, 2018), 25–31, 40–42, 70, 79, 133–34, 166, 192–99, and 228.

- For moments of black athlete activism and costs or punishments thereof, see Bryant, Heritage, xiii–xv, 3–6, 14–18, 4–53, 115, 216, and 221–29.

- For the greenwashing of sports heroes, see Bryant, Heritage, 82–85, 90, 94–97, and 220–21.

- Colin Kaepernick, quoted in Steve Wyche, “Colin Kaepernick Explains Why He Sat During National Anthem,” NFL Media, August 27, 2016; Christine Hauser, “Why Colin Kaepernick Didn’t Stand for the National Anthem," New York Times, August 27, 2018.

- See interviews in Etan Thomas, We Matter: Athletes and Activism, Edge of Sports (New York: Akashic Books, 2018).

- For the “shut up and play” response to Kaepernick's kneel and other athlete protests, see Bryant, Heritage, 3–9, 10–13, 42–43, 173–76, 185, and 188.

- M. Shawn Copeland, Enfleshing Freedom: Body, Race, and Being (Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 2010), 100.

- Bryant, Heritage, 15 and 19.

- For Kaepernick's spiritual and ethical awakening, see Angela Denker, “Colin Kaepernick and the Powerful, Religious Act of Kneeling,”Washington Post, September 24, 2017; and John Branch, “The Awakening of Colin Kaepernick,”New York Times, September 7, 2017.

- Damian Tromerhauser, “Faith Based: Former Nevada Standout Speaks at Local Church about Life, Athletics,” Daily Sparks Tribune, January 16, 2013.

- The “quarterback kneel” is described in the Official Playing Rules and Casebook of the National Football League, Rule 7, Section 2, Article 1 (c): “An official shall declare the ball dead and the down ended . . . when a quarterback immediately drops to his knee (or simulates dropping to his knee) behind the line of scrimmage.”

- Army veteran Nate Boyer played an important role in Kaepernick's decision to kneel. See Billy Witz, “This Time, Colin Kaepernick Takes a Stand by Kneeling,” New York Times, September 1, 2016.

- James H. Cone, God of the Oppressed, rev. ed. (1975; Maryknoll, New York: Orbis, 1997), 99.

- Ibid., 102 and 111.

- Kelly Brown Douglas [Kelly Delanie Brown], “God Is as Christ Does: Toward a Womanist Theology,” The Journal of Religious Thought (1989): 16.

I Wish to Reveal: A Conversation with Joyce J. Scott

Phoebe Wolfskill

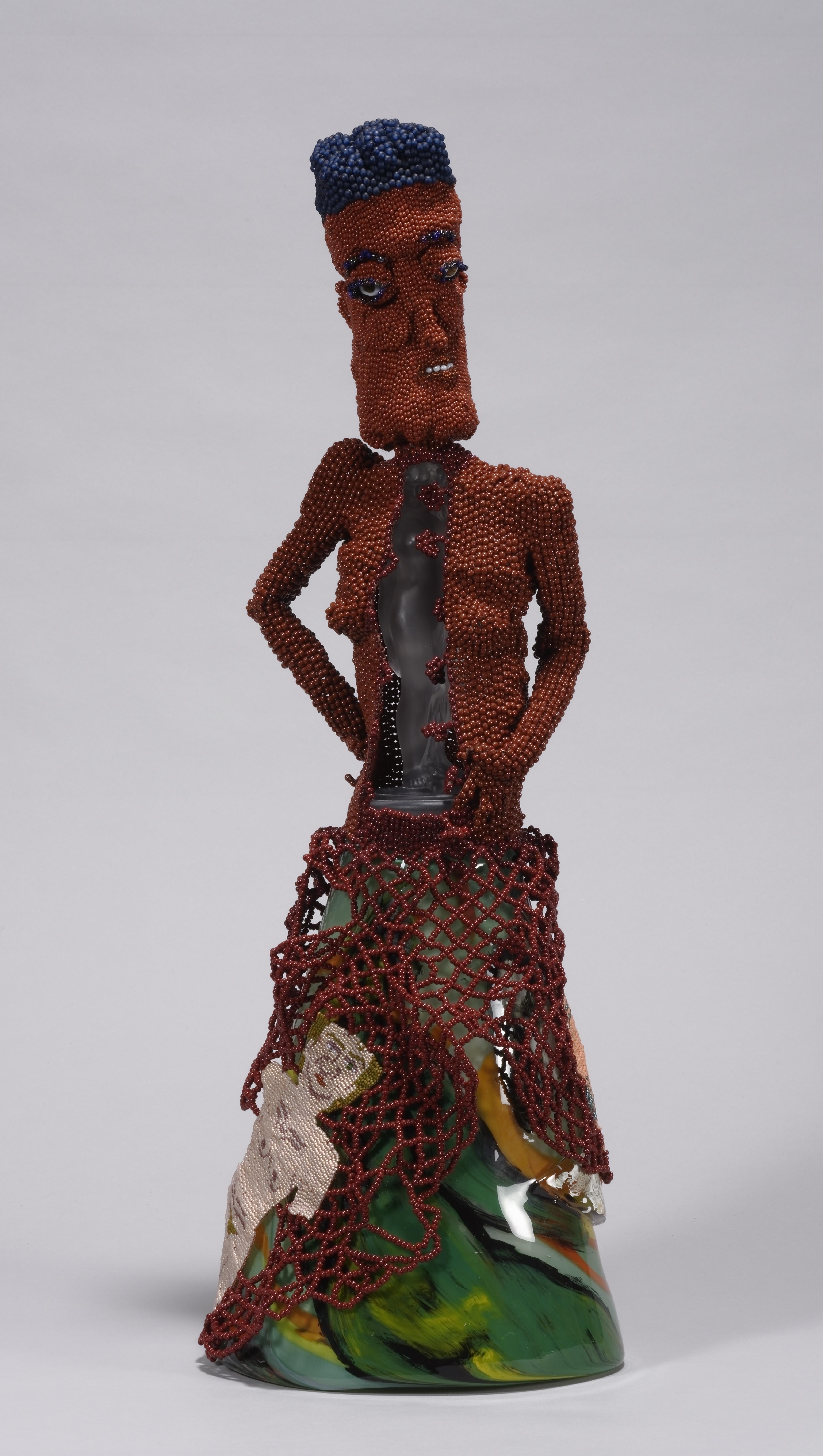

Sculptor and MacArthur Fellow Joyce J. Scott uses the physical properties of her materials—which include beads, glass, fabric, and found objects—to speak to America’s brutal history of race relations. Scott’s embellished and magnified black bodies render physical violence palpable, allowing for visceral and intellectual responses that prompt greater awareness of our collective racial past and present. Her body of work is stunningly beautiful in its materiality yet simultaneously cutting in its sociopolitical critique, bridging the gap between aesthetic innovation and humanitarian activism. In contemplating the inhumanity of the historical treatment of the black body in America—and, indeed, bodies worldwide—her work pushes us to regain our humanity.

Fragments of a Crucifixion focuses on artists who obliquely reference the crucifixion of Jesus in their work as a symbol of racial oppression (among other forms of oppression), and Scott's work fits squarely into this dialogue. While Scott's work is not featured in the exhibition at the MCA, attention to her sculptures and wearable art augments the show's focus on contemporary artists' use of religious themes to address injustice. I've met and enjoyed multiple phone interviews with Scott in preparation for writing my article “'Comedy, Pathos, Delight, and Horror': Joyce J. Scott and the Racial Body,” which will be published in the forthcoming arts issue of Callaloo: A Journal of African Diaspora Arts and Letters. My article investigates Scott's creation of distorted and hyperbolized bodies in works including Rodney King’s Head Was Squashed Like a Watermelon (1991), Cuddly Black Dick #3 (1995), and Still Funny: Mammy/Penis (2011), with a particular attention to how Scott's figuration and themes challenge both stereotypes of the black body and the propriety of the art object itself. The article foregrounds Scott's use of satirical humor and caustic wordplay as a means of addressing difficult subjects. The conversation recorded below takes a new direction by focusing on religious and spiritual signifiers in Scott's work. We discuss the artist's religious background, her concerns about racial and other forms of violence, her interest in global religious practices, and her approach to “fragments” as a theme and aesthetic trope.

Wolfskill Figure 1

Joyce J. Scott, Catch a Nigger by His Toe, 1987. Beads, wire, and thread; 8 × 10 × 14 in. Collection of Oletha DeVane and Peter Kojar.

Photo: Ken Ek.Phoebe Wolfskill I want to start with a piece from 1987 that you titled Catch a Nigger by His Toe. This piece is rather small but eye-catching and beautiful in its application of different textures and sizes of beads. When you examine the depiction of the tree in this work, you notice that it has claw-like fingers and attached to them a black man hangs upside down, which immediately suggests lynching. He's upside down hanging by his foot, and the title references the nursery rhyme “Eeny meeny miny moe.” So there's implied violence against black bodies on multiple levels. What motivated this work? How did it come to you, and how do you imagine your viewer responding to this piece?

Joyce J. Scott I think it was very clear then and is very clear now how race and racism—how hatred among people of different ethnic groups—has saturated our culture. It'll take a very, very long time to dispel this, if we ever do. I don't have any reason to tiptoe around our horrendous behavior toward each other. We don't really give thought to taking someone's life. We're ready to take the physical life or to kill the emotional life. That's just dastardly.

PW And is that why you render this not just as a straightforward lynching but link it with the nursery rhyme, which is more psychological?

JJS Yes. And that phrase is one that both black people and white people say. I grew up with it. So to me it is internally absorbed and repeated. As an artist I'm creating something that I want you to look at: the idea that someone's spirit can be so greatly disrupted. And remember that in all of these situations, everybody is injured as a result. There's an old saying about slavery that nobody is ever free. If you sit on somebody's head, they can't go anywhere, but neither can you.

PW Right. So when I was growing up, I always knew “Catch a tiger by the toe.” But when my mom was growing up, which was the 1940s and fifties, she remembers—

JJS “Catch a nigger by the toe.”

PW Yes. She admitted this to me with some embarrassment a couple of years ago. She was a white girl growing up in New Orleans, and that's what she learned.

JJS That was a while back. But that we may still be doing very similar things is what I'm pissed about. We've had time to evolve out of certain behavior. Somebody wanted to be the boss or make other people subservient to them. I guess humans have been doing that for a long time. The idea, though, that we are now at a point when we don't have to do that and we're still doing it means it's something with us—that it's spiritual, or, you know, a soul problem. That can be another word for it. It's directly related to Western culture, although it's not like every culture didn't have it. We just seem to have systemized it and held on to it in a different way. But we have the ability to change, and we need to change.

PW I've read that you grew up in a Pentecostal church. What did that experience mean to you, and how does it inform your work?

JJS Best thing ever. My parents were from North and South Carolina. The preacher at our storefront church was my godfather. When I became accepted into the congregation he preached with me in his arms. I did street ministry with them, and that was a great primer to being an actress. It is just surrounded and bathed in a kind of love that takes you outside of yourself. Something that delivers you—you're delivered into another place. Faith is an interesting thing. You have the crazy stuff for which you do not necessarily have a lot of proof. But you're still pursuing it. And that is really what church meant to me. It helped develop me as a person who believed in the future and faith. Because you know this is a storefront church led by people who didn't read and write very well. It was celebratory because it's the belief that you don't have to be locked into what you are—that you can change and you're not alone. Another thing about faith is that you're not alone.

PW Are there particular crucifixion scenes in the history of art that have stood out to you or inspired you in some way?

JJS I went to graduate school in Mexico and traveled around Central America. Actually, I have been blessed to travel the world. The crucifix is about really praising someone who's dying in front of you. But I recall the ones that are made by artisans in different places, where someone has hand carved a religious object or made it out of straw. I also have a couple of West African crucifixes that I've used in my work, and it's just the way that they so beautifully engaged with the wood. They allow the wood to speak in tone instead of painting it. Let the wood talk to me. That's a very powerful work for me. And you know I love going into an Italian church! I mean, there are flowers around and then it's covering up his genitalia, but there's enough exposed so you could see his muscularity and all that other stuff. And the nails, darling, the nails!

PW

Are there certain biblical stories and images that particularly spoke to you as well? Because when I look at Catch a Nigger by the Toe, the man in the piece is hanging upside down, and what I thought of was The Crucifixion of St. Peter (1600), which was rendered by Caravaggio with Peter attached to a cross and being lifted upside down with his bare feet jutting crudely into the viewer's space. Was that something you thought about when you made your own work?

Wolfskill Figure 2

Joyce J. Scott, Catch a Nigger by His Toe (detail), 1987. Beads, wire, and thread; 8 × 10 × 14 in. Collection of Oletha DeVane and Peter Kojar.

JJS Not that Caravaggio necessarily. I'm someone who went to a million years of art school. I studied a lot of European art and Asian art. In the old days we didn't study a lot of African art or Native American art. That was my quest. So a person being hung upside down. That's an old piece from 1987, and I don't remember all of the exact details. But one finds that kind of thing throughout history and throughout images all over the world. So for me it is a kind of global approach to what it must be like to be tortured like that.

PW I see. In your body of work more broadly there are numerous references to violent episodes from the Bible, like the crucifixion or the apocalypse. You reference these biblical themes many times, but through a translation into contemporary life. Do you see spiritual elements or possibilities for redemption—that there's the reality of violence, but also the possibility of salvation?

JJS Absolutely. That's why Buddha plays such a big part in my work. Because he wasn't a god. He was a human who worked very hard to evolve into this person who was in a state of not only reverence but also a kind of spiritual change that allowed him to be one with everything. And I believe that humans have the ability to evolve and change. I think we're very, very young. I think of the Earth as a squillion years old. If we're really young and pugnacious and hardheaded like kids, then we won't easily evolve and change to become more mature and do things right. You know we're always looking for voodoo and everything else to make that happen; we are self-medicating with drugs and everything else to find that place. I don't know if we know how to do it, but you know love is not an easy thing. Love is both the easiest and the hardest thing to attain. And empathy for others is the easiest and the hardest thing to do. So when you see a lot of my work, it's about just trying to find the route to that.

PW I've seen global religions represented in your work: a focus on Shiva and Buddha, among others. So you're looking to various cultures and how they take on these kinds of questions?

JJS Well, it's because we're just human. This really is humanity to me. I wouldn't expect somebody in India to be doing Jesus Christ necessarily. It's not that Christians aren't there, but that's not the basic culture. I would expect them to go on that quest through their own cultural realm. It doesn't mean, though, that I think less of it. It's just like, “Oh, that person has six arms, I wonder why.” I'm always very hungry to find out how humans have dealt with these questions. It's also how I like many religions or thought processes in which there is something that's happening and something that isn't. Something that's up and something that's down. How many cultures believe in the underworld being under the water, and how they do that? It's all very interesting to me.

PW I also sense skepticism in your work. I'm wondering if you think your work is more about questioning one's beliefs than believing itself?

JJS I don't know if I'm skeptical as much as I might be cynical. Sometimes. And I'm incredibly sarcastic and sardonic. I think that we are asses—we're really messed up in our inability to be wonderful to another human being. So I'm cynical sometimes. But you know love is the easiest and the hardest thing to do. You know it's easy to say, “Oh, I'm going to give something to a homeless person, but I don't want them living next to me.” Or, “I believe that everybody should have their rights, but I don't want any black people in my neighborhood.” It's some kind of human thing. We don't seem to be able to work that out very well.

PW I asked you in an earlier conversation—probably a couple of years back—about another work, Rodney King’s Head Was Squashed Like a Watermelon. The color palette is black, green, red, and white, and I always assumed this choice of colors effectively conflated the head with the watermelon. But you mentioned to me that it was a reference to the four horsemen of the apocalypse. The idea of the apocalypse also appears in the later, related piece Three Graces Oblivious While Los Angeles Burns (1992), which features King's decapitated head at the top of it. Are there works about the apocalypse within the history of art that have particularly struck you? If you look at the history of Christian art, for example, there's so much artistic freedom in scenes of hell and the apocalypse, whereas images of the Christ child are often more standardized. There wasn't the same kind of iconographic freedom. So are there particular apocalyptic images that inspired you?

Wolfskill Figure 3

Joyce J. Scott, Rodney King’s Head Was Squashed Like a Watermelon, 1991. Beads and thread; 5 1/2 × 12 1/2 × 9 in. Philadelphia Museum of Art, purchased with funds contributed by The Women's Committee and the Craft Show Committee of the Philadelphia Museum of Art, 1995, 1995-81-3.

JJS Fire is very frightening to me. So reading about fire in the Bible is terrifying. And drowning in the Bible is terrifying. That we've been having tsunamis and things lately, in our world—it's pretty amazing to me. We're frailer than we think we are. And I don't know if we realize that when we talk about the end of the world, we're really not talking about the end of the world. We're talking about the end of us. The world will be just fine without us.

PW Regarding the exhibition's focus on fragments—so much of your work presents a fragmented body. In both of the Rodney King pieces, for example, the figure of King is decapitated. Why do you think that's a prominent part of your work? What is it that motivates you to deal with the body as a set of fragments?

Wolfskill Figure 4

Joyce J. Scott, Three Graces Oblivious While Los Angeles Burns, 1992. Glass, beads, wire, and mixed media; 21 × 9 7/10 × 9 in. Collection of The Corning Museum of Glass, Corning, NY, 97.4.214.

JJS You know there's something frightening about a body that's in parts and not together. And there's also the importance of the fragment. Maybe the arm is the most important part for that piece, let's say, so that's what I'm working on. Although in the last show that I did, we had a lot of full figures. But there's still a lot of armless things. If I'm working with a gaffer—if we're doing glass—we'll get to a head and a torso. For me that opens it up to decide whether I'm going to put arms on, and then how to make the arms and what the arms can do. It is also about the idea that if someone doesn't have arms, it means they cannot control things.

PW So I'm thinking of these fragments: the heads, the detached phalluses. I've written about that in my other article on your work. There's also the work that's at Dartmouth College's Hood Museum, Mammy Under Undue Influence (2007). The figure's skin is almost like a garment that's come undone, and another body is underneath it. They're very tactile pieces, but disruptive because the skin or the body is torn apart.

Wolfskill Figure 5

Joyce J. Scott, Mammy Under Undue Influence, 2007. Blown, cast, and lampworked glass, and beadwork (peyote stitch); overall: 27 9/16 × 8 11/16 × 7 7/8 in. Hood Museum of Art, Dartmouth: Purchased through the Virginia and Preston T. Kelsey 1958 Fund; 2007.51.

JJS But see, you've just said it: they're disruptive. They're meant to be disruptive. They're meant for you to see this beautifully crafted thing and come up and be shocked. Yes.

PW There's a piece that you made for the 1991 Spoleto Festival in Charleston, South Carolina, titled Believe I’ve Been Sanctified. This was a large-scale, site-specific work in Charleston. I believe some 40 percent of the Africans that entered this country came through the port of Charleston.

Wolfskill Figure 6

Joyce J. Scott, Believe I’ve Been Sanctified, 1991. Beadwork and mixed media; 17 × 15 × 13 ft.

Photo: John McWilliamsJJS And my mom is from South Carolina.

PW I'm from Columbia, South Carolina, actually. And you know, Charleston is a place that has yet to reckon with this history. In Believe I’ve Been Sanctified, you used existing columns from an old Charleston museum's ruins, and then you attached beautiful-looking beads that recall weeping, like weeping willows, and then you've got a figure in the center hanging by its neck.

Joyce J. Scott, Believe I’ve Been Sanctified (detail), 1991. Beadwork and mixed media; 17 × 15 × 13 ft.

Photo: John McWilliamsJJS You know I can tell you about that piece—that was my first really giant work. It was maybe 15 or 17 feet tall. And it was when someone said, “Okay, you can do it. Okay, we'll pay for it. Oh, okay, you're going to do what? How many yards of beads—you're gonna what?” At the bottom of it there is a funeral pyre. This person—or this entity—is being lynched. Also the tree is upside down. It's over a pyre that was lit in the night like an opera stage. I actually intended to come and sing there at night. But it was vandalized immediately.

PW How did people respond to this? What happened after it was vandalized?

JJS Well, the only thing that was rigged was the light, so everything else was good. I was told there was a homeless man living under the building. There was an opening under it, and he was angry about the light. I'd taken over his space. And he broke it. Another thing I heard was that they used that site for weddings, and somebody was upset because they wanted their wedding there. For all I know a bunch of artists didn't like it and they went and broke it. What do I know? It was vandalized.

PW What inspired the title Believe I’ve Been Sanctified? Rather ironic, it seems. Can you talk about that?

JJS I think it has a lot to do with burning—burning candles, people being burned in effigy, people actually being burned as a punishment. That's what I think with all of those things.

PW Wow. And what are the very bold colored pieces underneath that make up the pyre? The burning pieces?

JJS Wood. They were done for me by a college student. I said that I wanted a bunch of wood and that I wanted this color. They got it for me when I got there.

PW What were some of the other responses to the work? This is a loaded geographical space, it's a huge piece, and it's in the public.

JJS While I was installing it, I never said it was a lynching. People would come up, and I'd say, “I'm still working on it,” because I thought that if I said it was a lynching I might not get it through to the opening. People were really enamored by its size and use of beadwork. They may see beads all the time, but beads hanging from trees at the top of an old building is different.

PW You've made necklaces throughout your career—these very elaborate art pieces that can be worn. Back in 1981 you had a lynching necklace.

JJS And some are about women being killed. Some are about overt racism.

Wolfskill Figure 8

Joyce J. Scott, Lynching Necklace, 1998. Glass beads and thread; 11 × 6 in.

Courtesy of Goya Contemporary Gallery, Baltimore.PW Right. These figures are often fragmented or violated in some way. Thinking about lynching and the noose around the neck that figures elsewhere in your work, one wonders if these necklaces are heavy objects. Is the work to some extent a literal reminder of the narrative taking place? I'm thinking of the weight of the noose as a physical presence that you feel as you move around.

JJS Well you have to make an emotional and physical commitment to wear work like that.

PW I'm sure.

JJS But beads are surprising how? Because they are made out of glass. If you have enough of them, they do tend to have weight to them. They also have a temperature to them. They are something that can be two-sided, as in life. If they're really beautiful and filled with commentary, then you're going to have people who are going to come up and engage you. And that's the whole thing about whether or not you can actually be engaged by others. Because if you're wearing something about lynching, then are you ready to be ass whipped? Are you ready to be engaged with people in that manner? So for the wearer, it's a stand with both of your feet on the ground. That's why some buyers really love them but will never wear them. I say, “I made it to be worn.” They're like, “Yeah but I don't have the chutzpah for that.”

PW But you wear them.

JJS Absolutely.

PW Do you get questions or comments from strangers?

JJS Sure. One of the things is that people sometimes want to buy something off me. Because they know it's a commodity. Sometimes I think it's because I'm black, and that's another image for people. It's also people wanting to be disruptive, and I don't get too upset about that. But it is running right into your personal space, right up where your titties are.

PW Yes, it's very personal.

JJS Now that's a certain power I have. Because people forget. And then they ask, “Is this the one who was just killed?” referring to one of many recent black deaths. Yes, this is a necklace about it.

PW A more recent piece is the Lynched Tree (2011–15) for Prospect.2 in New Orleans, where the sculpture was actually positioned in the tree. I saw it in the MOCA Cleveland show, where it was positioned differently because it was in a gallery space. But it's a nude female figure with glass and other materials spilling out.

Wolfskill Figure 9

Joyce J. Scott, Lynched Tree, 2011. Plastic beads, glass beads, blown glass, thread, wire, and mixed media; install dimensions variable, approx. 106 × 42 × 15 in.

Courtesy of Goya Contemporary Gallery, BaltimoreJJS The figure is a haint, which is a ghost in the South. You know what a haint is? The haint was placed up in a tree for that installation.

PW So is that what she is? A ghost?

JJS Or she is many things. She's a chameleon, and she becomes that kind of thing. She's a ghost. In the piece at Tulane she was in the tree and falling from her neck with glass branches. And I don't even know what that was about. So instead of her being lynched, she lynched the tree. She really has been this portal. She has things pouring from her body, but she also relates to prayer, perhaps.

Wolfskill Figure 10

Joyce J. Scott, Lynched Tree (detail), 2011. Plastic beads, glass beads, blown glass, thread, wire, and mixed media; install dimensions variable, approx. 106 × 42 × 15 in.

Courtesy of Goya Contemporary Gallery, BaltimorePW That's really interesting. I read her more as a violated figure, perhaps because of the title and because of what I saw.

JJS I certainly think that's part of it. But you know when I look at these—when I look at what I do and know what I do—they're not only of the moment. If there's a human there, then that human had an entire life before that. But I like that it could be whatever it is for that person. If they are mollified. If they are frightened. If they define beauty. Or if they wonder how the hell I did it. Whatever comes to them is what I want them to have.

PW Yes, well I found this interesting because of her scale but also because she's a pink female, and that seems to be less common in your work. So I guess she's to be read as white. Was it the operation of the haint that made you choose that color?

JJS I think it's because you can't tell me what to do. You can't tell me I can't make white people.

PW Absolutely.

JJS

I believe in my work. I believe that I should be able to stand up for it. And so I will take images and do imagery that is frightening even to me when I’m making it, but it doesn’t mean that I’m going to back off from it.

PW Regarding larger themes of the violence of humankind—not just in terms of specific races and genders, but more broadly based in relationships of power and control—does it sometimes become too difficult to address these themes? Does it become too overwhelming?

JJS Usually I work on more than one piece at a time, so I'm not just dwelling in one work like that. I have my own kind of therapeutic methods that help me get around it, but I am an African American woman who lives in Baltimore in the inner city. There's no way I can squirm out of that. I need to be consistently on the cusp of creating something and really forcing my head to work at optimum speed, in ways that we're told we can't do. To be in command of yourself and try to go beyond what's usually expected of you, and then to have the ability and the context to do it—that's the amazing place to be. I feel incredibly blessed to be an artist in that way. I don't believe that artists are the only ones with it. But I think we're the ones who command the space, and we're the ones who stand up and take it as our life force.

PW Do you see art as a spiritual practice?

JJS Absolutely. Or I'd be dead, or I'd be a mass murderer or something. I have a really great sense of humor. I make money off of it as well. Many times it allows me to get anger out, and humor out, and things out. There are all kinds of things you don't want to say to another person, and you need another vehicle. Art is that. It's so great for that.

PW Does your art preach? But maybe that's the wrong word. I mean, obviously you're making ethical points and pushing self-evaluation. But do you seek to convert in a way?

JJS That's out of my power, and what would I be converting someone to? I don't necessarily have any answers right. But I wish to educate. I wish to reveal. Because my best voice is as an artist. I use my ability to say, “Did you see it this way? Have you ever thought about it that way?” That's what I wish to do.

In Conversation with Paul Pfeiffer

Chanon Kenji Praepipatmongkol

Paul Pfeiffer is one of the most visible artists who emerged at the turn of the millennium. With his mesmerizing digitally manipulated video works, Pfeiffer won the Whitney Museum's Bucksbaum Award in 2000, the largest private art prize in the world at the time. Through cutting and retouching found footage, he grapples with the viewer's relationship to an ever-accelerating deluge of images circulating around the globe through mass media. While Pfeiffer's critical engagement with media representations of race and gender has been the subject of numerous interviews, less attention has been paid to religion's relevance to his exploration of body politics. Indeed, the relationship among spectacle, celebrity, and religion figures prominently in Pfeiffer's work, whether in comparisons of sports stars and biblical personages (Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse, 2000) or fans of Justin Bieber and followers of megachurches (Incarnator, 2018).

The conversation below takes its departure from Pfeiffer's work Fragment of a Crucifixion (after Francis Bacon) (1999), a centerpiece of the MCA exhibition Fragments of a Crucifixion and the inspiration for its title. The second part of the interview delves into Pfeiffer's relationship with religion, which is at turns art historical, ethnographic, and deeply personal. Exhibition curator Chanon Kenji Praepipatmongkol and the artist discuss a range of projects spanning Pfeiffer's career, beginning with his participation in Asian American art shows of the early 1990s and ending with his recent research into histories of slavery at the University of Georgia.

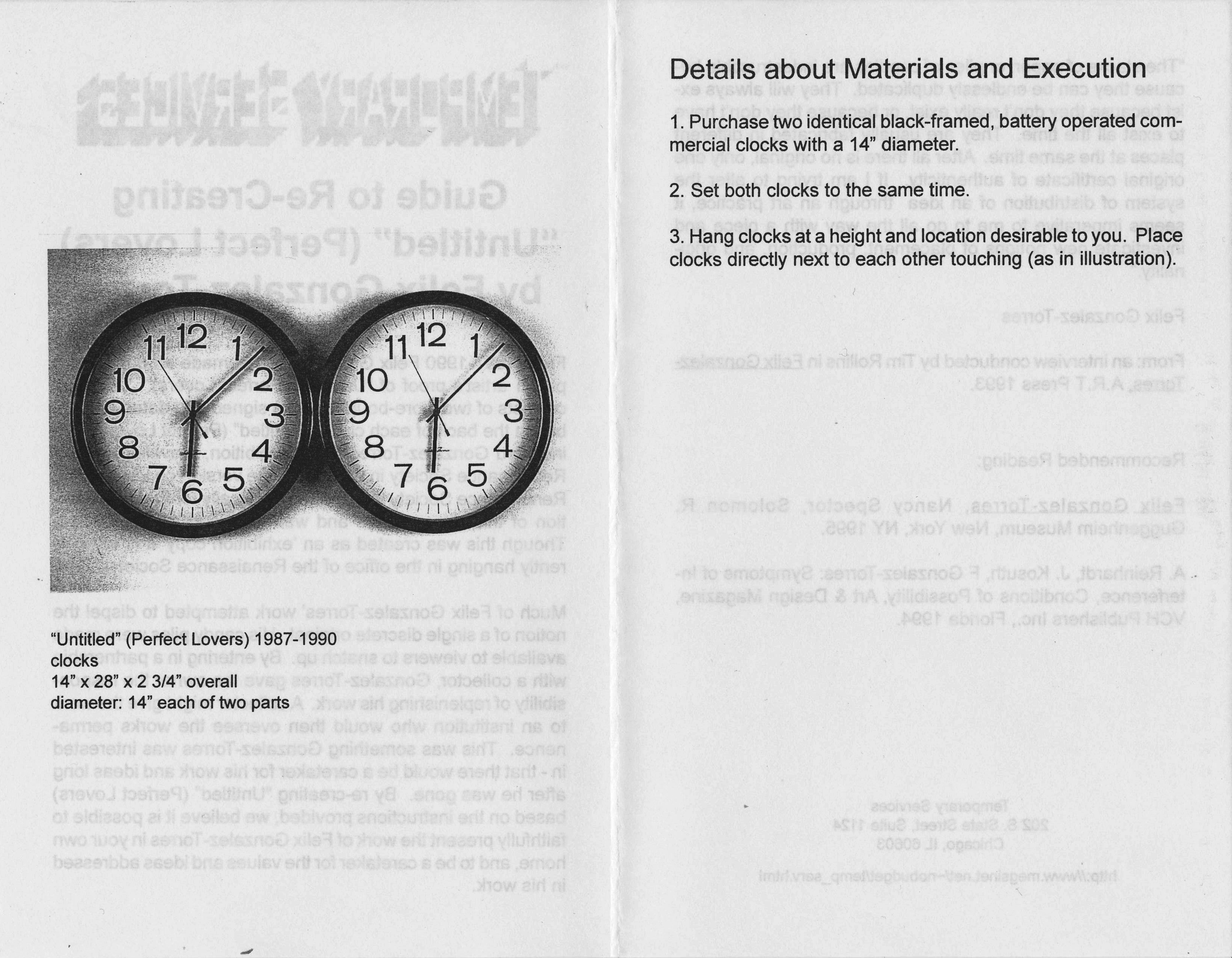

Pfeiffer Figure 1

Paul Pfeiffer, Fragment of a Crucifixion (After Francis Bacon), 1999. Digital video loop, projector, and armature; 5 minutes, 20 × 5 × 15 in. Edition of 3, aside from 2 artist's proofs.

Courtesy of Paul Pfeiffer StudioFragment of a Crucifixion

Chanon Kenji Praepipatmongkol Could you, briefly, describe your work Fragment of a Crucifixion (after Francis Bacon) (1999)?

Paul Pfeiffer I would start with the title. Fragment of a Crucifixion comes from a painting by Francis Bacon made in 1950. In Bacon's version, two figures are suspended on a cruciform-shaped armature, which is surrounded by a vast, spatial void. The figures appear to be disintegrating. One has a screaming head, which Bacon imported from the early Russian film Battleship Potemkin (1925). Its arms are raised and outstretched, recalling the iconography of the crucifixion in religious paintings. My video came from the experience of watching a basketball game and being reminded of Bacon's painting. The basketball court is the armature, the dome of the arena is the spatial void, and at the center are the suspended figures of the basketball players. There's one basketball player in particular: he's just made a slam dunk, and he's celebrating by screaming. I took one or two seconds of video footage of this moment and looped it. And by looping it, the scream continues infinitely, so it becomes ambiguous as to whether it's a scream of pleasure or a scream of pain. That's where I stop.

CKP What you describe as the psychological experience of the work and the manipulation of that psychological experience seems so central to the work. When I approached it, initially, seeing the smallness of it and the handle of the video projector jutting out, my first thought was that it makes reference to sculpture. There's a smallness and an almost fetishistic quality to its physical nature. But when you watch the video for a while and see this basketball player stuck in a loop, the reference then turns to painting: the stasis that is painting. Thinking in terms of physical medium, though, it is video. The work really eludes a distinction of media. What you're getting at is how all of these media references can be used to manipulate the quality of attention that the work then holds. How do you feel about that kind of description?

PP

In a sense, the viewer’s attention is the real material to be shaped. I’m generally interested in the phenomenology of different media and how these relate to the context of art-making. My understanding of phenomenology has to do with the proposition that reality does not exist in an already-given state outside ourselves. It’s actually produced in the interface of perception. The production of knowledge and the study of the limits of understanding, in some ways, have to start with this interface. This is precisely the point where media can manipulate perception.

I recently spoke with a philosophy teacher who said he believed that, properly speaking, philosophy ends with the emergence of phenomenology, which I found astounding. It was his way of saying, “I’m not interested in phenomenology; that’s no longer philosophy to me.” For him, it’s the tipping point where you go from classical philosophy to something like criticism. There’s a hierarchical relationship, he’s saying: philosophy is serious, criticism is not as serious. The dividing line is phenomenology.

CKP I read phenomenology as a moment when philosophers began to admit to a kind of lived experience that did not necessarily depend on analytical propositions or strictly delineated beliefs. It is something that needs to be thought of at the interface of psychology and the world, and how that relates to embodiment of, say, brown bodies or black bodies.

PP

Or the queer body. To me that is getting to the central point. That, to me, is the matrix of the body.

CKP Can I push you further in that direction? Fragment of a Crucifixion puts the body on this loop that, on the one hand, shows really intense human emotions—jubilation, ecstasy, anger, pain. It's intensely human and intensely psychological. But there's a flip side to it, which is that after you watch it for a while, the loop turns the human into something extremely mechanical and inhuman, becoming energy that's stuck. How do you think of these intertwined concepts—the human, the inhuman, and the mechanical?

PP

Your question makes me think of Jacques Lacan. Specifically, the idea that in the developmental process of every child, there’s this thing called the mirror stage that signifies the moment when the child, this sentient being, recognizes itself in the mirror. This is associated with ego formation. What’s interesting to me is that there is a period of months from birth to a certain age before the mirror stage when that ego formation is incomplete. At this point, sensory experience is fragmentary; there is not a unified selfhood to contain sensory experience. It’s just in fragments: the mother’s breasts, a hand, an eye. There isn’t a structure yet to organize it into a sense of wholeness. Although we think of a kind of sensual, essential humanness as something that you’re born with, the implication of Lacan’s studies is that people are actually born not human. They become human at the point where the ego is formed. And even then, it takes time for it to develop to a point when the child is educated enough to claim to be fully socialized. In Michel Foucault’s terms, there is a process of discipline and punishment to get to a state of full human formation. In short, I feel that the relationship between the human and the inhuman, or the not-human, is much more troubled than we usually think.

Please excuse me for intuiting this connection, which feels way too general, but to me this is also a Buddhist lesson, or at least it reminds me of certain Buddhist lessons that I’ve been exposed to through Lawrence Chua. There are certain meditations intended to focus your attention on the idea that you are born into the trauma of blood and shit. Whatever that is, it is not properly thought of as human in the sense of a civilized, socialized being. At the point of birth, we’re more like an animal than a human, to put it one way. You can say that to focus on such things is a kind of regression. Why focus on aspects that we’ve moved past? We’ve adopted a civilized nature. But in becoming civilized, human identity also becomes racialized or gendered in a hierarchal way. To me it is very interesting to imagine the possibility of identifying with something other than the aspiration to assume human identity in a hierarchical sense.

CKP It's fascinating how you've put it. Your comment about regression and the inhuman or prehuman returns me to your interest in the stadium as an archetypal space in human history. It seems that we're returning to a prehistoric arena, reenacting a primal violence and our being drawn to that spectacle of violence.

PP

It’s intriguing to think of identity formation on a primeval level, going back to the abstract codes of classical architecture—the most ancient patterns of thought in the Western tradition—to investigate the roots from which enduring distinctions such as human/nonhuman were first formulated. It’s not just ancient history. These are patterns of hierarchical thinking that endure into the present. The multicultural movement of the 1990s was an important moment of politicization for me, providing a way to challenge the limits of Eurocentric history. The ways that they were being formulated in the 1990s seem too easy to co-opt, too limited, not to go far enough. The idea of finding an alternative in these more abstract codes was something powerfully intuitive to me.

Worlds in Collision

CKP I understand that you grew up in several places—Hawai'i and the Philippines, among other places—in part because of your parents' work with the Methodist Church. Could you speak about this religious story of your childhood?

PP

I was born in Hawai’i, at a moment when my father had gone back to school at the University of Hawai’i and was working on his PhD in ethnomusicology. He was doing his fieldwork as I was growing up, and every summer he would go to the Philippines and make field recordings of indigenous musicians in the southern Philippines, mostly Mindanao. From as early as one or two years old, I was traveling back and forth periodically between Hawai’i and the Philippines because of my parents’ involvement with music education and performance in both places. While he was doing his field recordings, we stayed at my grandparents’ place in Dumaguete City, which is the home of Silliman University. It was founded in 1901, and my grandparents and my parents were associated with it. Silliman is a Protestant university, which is very unusual in the Philippines, an overwhelmingly Catholic country. Later on, my family actually moved from Hawai’i to Dumaguete, where my mom became the director of the music school at Silliman. At that point, I was going to high school at Silliman, which is a liberal arts education with a pretty central Protestant religious component.

CKP You eventually moved to the States to do your BFA in San Francisco and MFA in New York City. I was looking back at articles on your work from the early 1990s and was struck by your close involvement with the Filipino-American community and magazines like Filipinas. What was that period like?

PP

I moved to New York from San Francisco in 1990. Just before I moved, by happenstance, I attended an event called “Worlds in Collision” at the San Francisco Art Institute (SFAI). It was a conference of artists of color organized by Carlos Villa, a Filipino-American artist who lived for a long time in New York but then settled in San Francisco and was teaching at SFAI. The event really galvanized my consciousness of the intervention into art history that was coming from a very diverse group of artists—there were artists of color, but also queer artists and artists with a feminist discursive background. It was very moving to me. In retrospect, up until that point, I had a lack of investment in art history. I remember struggling to stay awake in art history classes at the Art Institute, but I remember feeling riveted at “Worlds in Collision.” These were people who could be my uncles and aunts talking about art history! It was the first time I really experienced that. The conference set the stage for what happened when I moved to New York and what became known as the multiculturalism movement. In 1990 in New York, there was a huge debate going on about the canon—the cultural canon. The Culture Wars were playing out, and the excitement at the time was in these kinds of organizations. ACT UP. The Guerrilla Girls. Living in the East Village, that's where the action was. I jumped in.

CKP In New York, one of the early events you participated in was Santo Niño Incarnate, a sculptural installation commissioned and curated by Cee Scott Brown in 1994 when he ran the Art Matters Foundation. Can you describe how the project speaks to that charged moment of multiculturalism?

PP

I suppose we’re talking about my network at the time. I was hanging out with the Asian-Pacific Islander caucus of ACT UP. That caucus was trying to make sense of how to build a politicized awareness of the AIDS crisis: how it was playing out in first-generation Asian immigrant communities, and how it would make sense culturally to bring this conversation to them. We worried that they were being left out of the ACT UP conversation.

I remember the project you mentioned, Santo Niño Incarnate, where I used the image of the Santo Niño but rendered it in transparent resin. I was thinking of it as a specific Catholic icon, but by rendering it transparent in a way, it became even more open to a proliferation of readings. I went around asking the Asian-American LGBTQ community to contribute photographs of themselves with loved ones, which I then cast inside these transparent statues. The idea was to take that aspect of Catholicism that has to do with an openness to all parties. At some point, I discovered that the roots of the word “catholic” are Greek, relating to ideas of universal or common experience, or to an attitude of all-embracing acceptance of diverse customs. These roots predate the use of the term Catholic in reference to the Christian church, and the even later use of the term to delineate the notion of a “true” church distinct from other “untrue” churches. In a very intuitive way, to take this very popular and accessible image of the Santo Niño and further explode it meant thinking of it as something that could be individualized and could contain the widest possible range of content.

Given that I was coming from a Protestant background, there was this moment in the 1990s when I started to specifically gravitate towards the possibility of utilizing Catholic imagery as a way of speaking about things. I remember telling my family a little bit about what I was doing. Or actually, maybe they just saw pictures. I made this sculpture of the Virgin Mary with a kind of cape made out of silver condom packets. The silver of the condom packet is very seductive to me visually. It was playing off the abstract reflective quality of that silver material and, obviously, the provocation of the sexual association. I remember when I showed it to my mom, her response was, “Why are you doing that? We’re not Catholic. Protestants don’t believe in the Virgin Mary. Why are you doing that?” Somehow, eventually, a picture of that sculpture ended up on her wall. I guess she got over it.

CKP What you're talking about—your interest in the shiny surfaces of the condom wrapper—seems to be particularly of that moment. Artists of color didn't want to be pigeonholed as merely ethnic artists. Layering body, sexuality, and religion allowed you to arrive at something more.

PP

There was an interest in eluding the limits of a very categorical identity-based discourse of the time, which I have to say, coming from Hawai’i, seemed particular to the East Coast. It wouldn’t make sense to have this conversation in Hawai’i or even California. If, like me, one was raised moving between Asia and the United States and Hawai’i, the idea of subscribing to this identitarian politics seemed too prescriptive. The adoption of the religious image was an attempt at scrambling that.

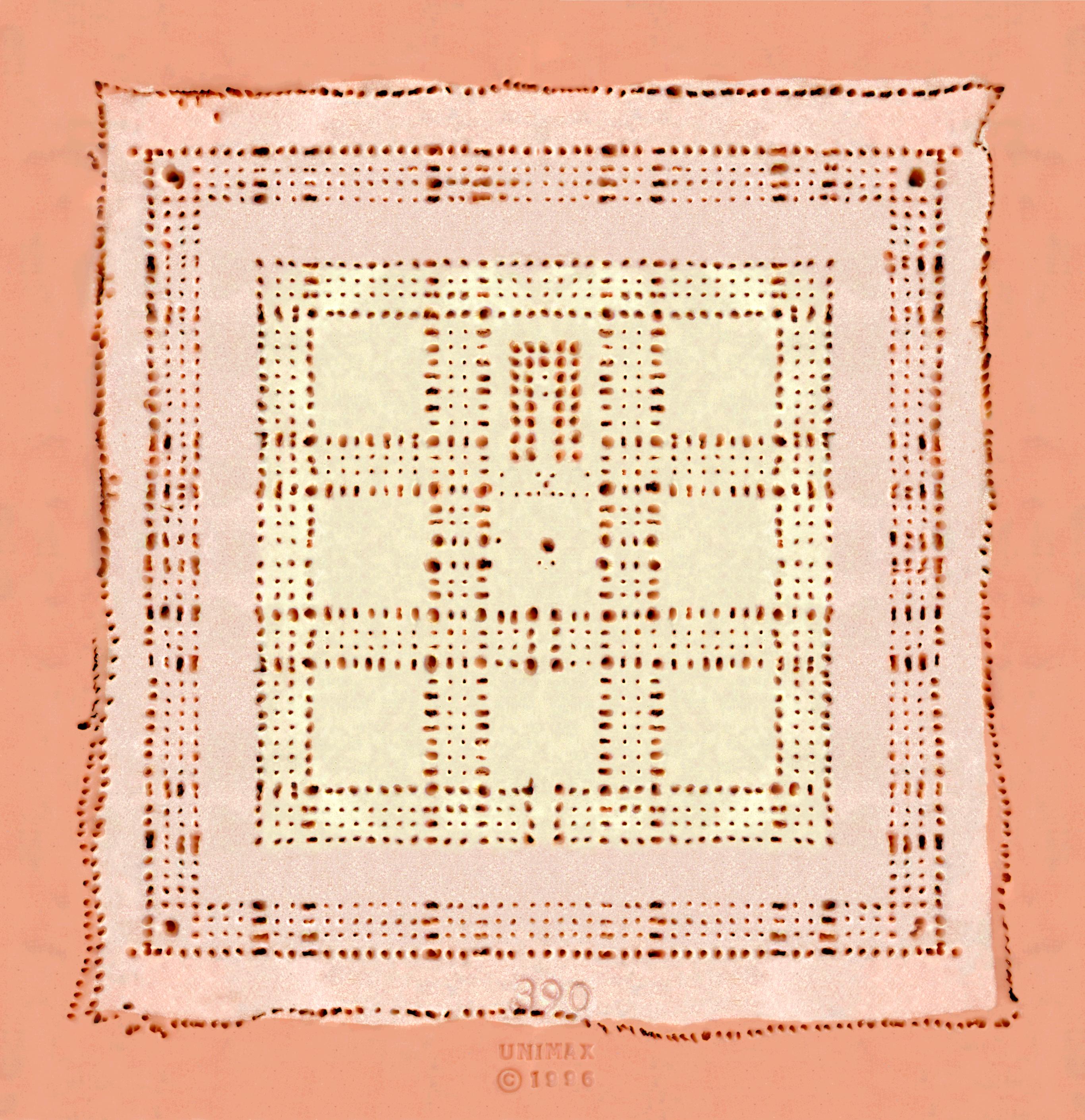

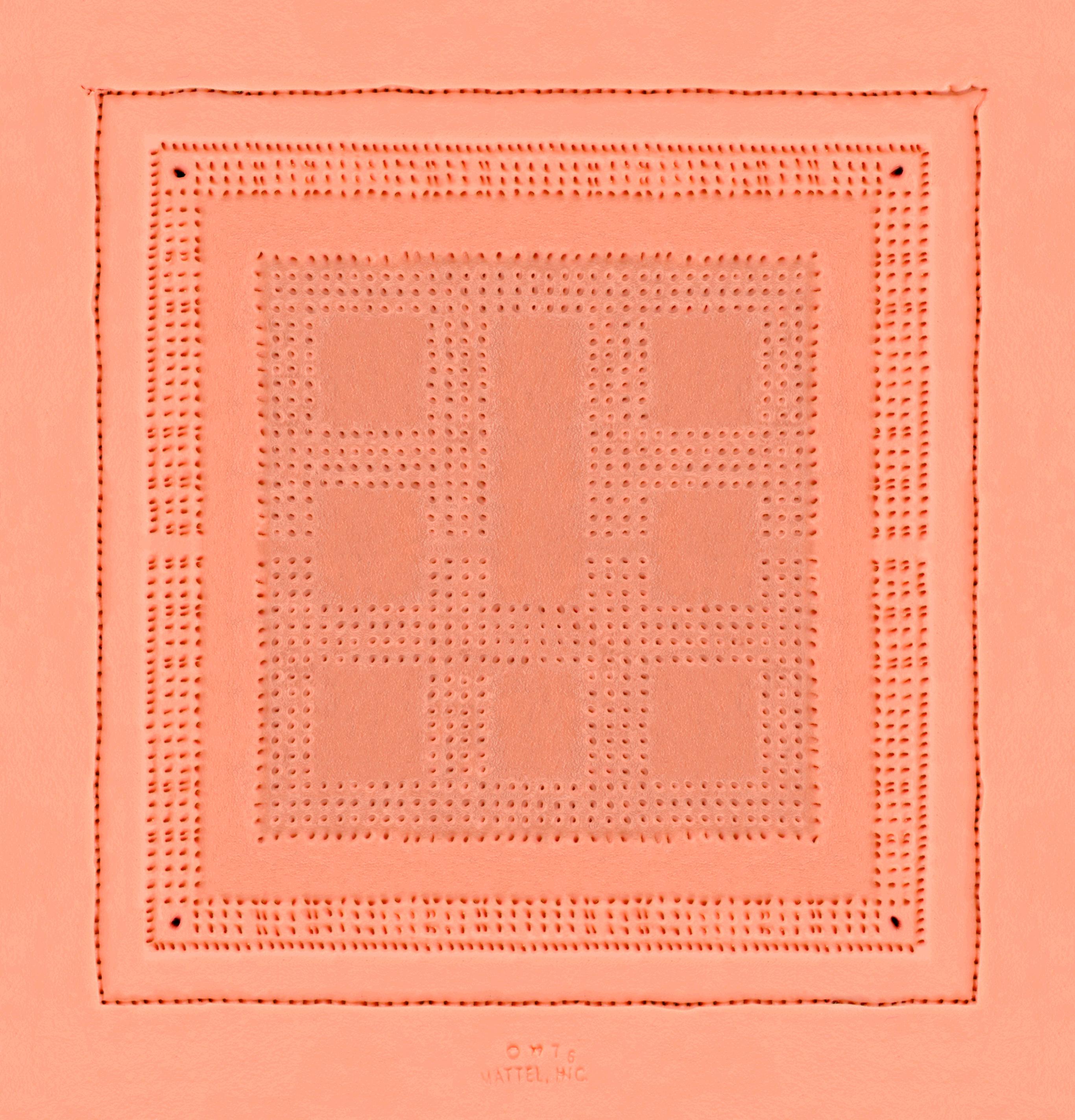

CKP One of your early works that dealt with religious imagery was the series Temple of Solomon—photographs of Mattel dolls with their hair parted to reveal a geometric pattern, which looks like an architectural floor plan. What struck me about this series was this inscription of something that has deep religious connotations onto a contemporary commodity object—dolls that reproduce archetypes of the blond, brunette, or ebony. This is a strange and powerful collision.

Pfeiffer Figure 2

Paul Pfeiffer, Temple of Solomon / Blond (After Villalpando), 1998. Digital chromogenic development print; 4 × 4 in. Edition of 3, aside from 2 artist's proofs.

Courtesy of Paul Pfeiffer Studio

Paul Pfeiffer, Temple of Solomon / Brunette (After Villalpando), 1998. Digital chromogenic development print; 4 × 4 in. Edition of 3, aside from 2 artist's proofs.

Courtesy of Paul Pfeiffer Studio

Paul Pfeiffer, Temple of Solomon / Ebony (After Villalpando), 1998. Digital chromogenic development print; 4 × 4 in.

Courtesy of Paul Pfeiffer StudioPP

I love connecting these dots. There's a certain point where the extension of the exploration of religious iconography led to looking at ground plans of basilicas. I remember reading one treatise on classical architecture in particular, a book called Architectural Principles in the Age of Humanism (1949) by Rudolf Wittkower. The central point was that the principles explored in the Renaissance were being recycled from antiquity in a very conscious way. There were ideas about the most primary proportions and tropes in architecture that, as it turns out, were not just architectural, but were more broadly aesthetic principles that applied equally to music, painting, and really all the arts. The agenda of the Renaissance really had to do with wanting to see themselves as the inheritors of certain aesthetic codes that, in a sense, were fundamental as far back as one can go in Western culture. The figure of the stadium or coliseum started to emerge as something very important, because in these books of classical architecture, it was one of the principal building types. It also connects to something that, at the time, I considered to be one of the most important contemporary architectural formulations: Madison Square Garden. Aesthetic codes aren't just about the design and decoration of buildings, but they describe on an abstract aesthetic level the essence of cultural identity.