Cruising the Collection: Queer Images at the MCA

Hal Fischer, Street Fashion: Jock, from the series Gay Semiotics, 1977/2016. Carbon pigment prints on Canson Photo Gloss Premium RC paper in handmade case with denim covering. Collection Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago, gift of Albert A. Robin by exchange, 2015.12.2.

In late May, protests and riots erupted across the United States in response to the murder of George Floyd, a Black man, by white Minneapolis Police Department officer Derek Chauvin.[1] Much media coverage, political rhetoric, and public discourse has been devoted to debating which forms of resistance are effective at creating lasting change. We can look to LGBTQ history to see how collective actions such as riots in response to injustice and inequity have affected long-term change. In fact, the now-ubiquitous Pride began as a riot. On June 28, 1969, the New York Police Department raided the historic gay bar the Stonewall Inn. Queer people were routinely harassed by the police during this era, and raids were not uncommon. Yet this time, the patrons fought back. The ensuing six days of protests and riots are credited as the beginning of the LGBTQ civil rights movement.

LGBTQ+ people have been persecuted throughout history for deviating from heteronormative society. In the 20th century these oppressive conditions necessitated the creation of clandestine networks of bars such as the Stonewall Inn, bathhouses, bookstores, private homes, public parks, and other safe spaces where queer people could connect. In parallel, codes were developed that allowed LGBTQ+ people to identify each other in public without disclosing their identity more broadly. To cruise is to learn these codes and traverse these networks in search of love, lust, and kinship; thus, cruising is way of life for queer people.

Because of the bravery of LGBTQ activists like Marsha P. Johnson and Sylvia Rivera, who were among the first to resist at Stonewall, things have gotten better for LGBTQ+ people in the United States and many other parts of the world.[2] Art has played a role in making the LGBTQ+ community more visible to broader society; many queer artists seek to rectify the repression of representation of LGBTQ+ people through their work. Photography in particular has proven to be a potent medium for documenting queer life.

On this essayistic cruise we’ll take a look at some of these image-makers in the MCA Collection and the subjects of their attention. As part of the MCA’s holdings, each of these artworks was, at one point or another, purchased by or gifted to the museum. By keeping these works in the collection, the MCA asserts their cultural value and artistic importance. While queerness may not be a major theme of the MCA Collection, as with cruising in real life, wonderful things can be found in the niches.

Gay Semiotics

Hal Fischer

Street Fashion: Jock, from the series Gay Semiotics, 1977/2016

Carbon pigment prints on Canson Photo Gloss Premium RC paper in handmade case with denim covering

Collection Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago, gift of Albert A. Robin by exchange, 2015.12.20

Hal Fischer

Street Fashion: Jock, from the series Gay Semiotics, 1977/2016

Carbon pigment prints on Canson Photo Gloss Premium RC paper in handmade case with denim covering

Collection Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago, gift of Albert A. Robin by exchange, 2015.12.7

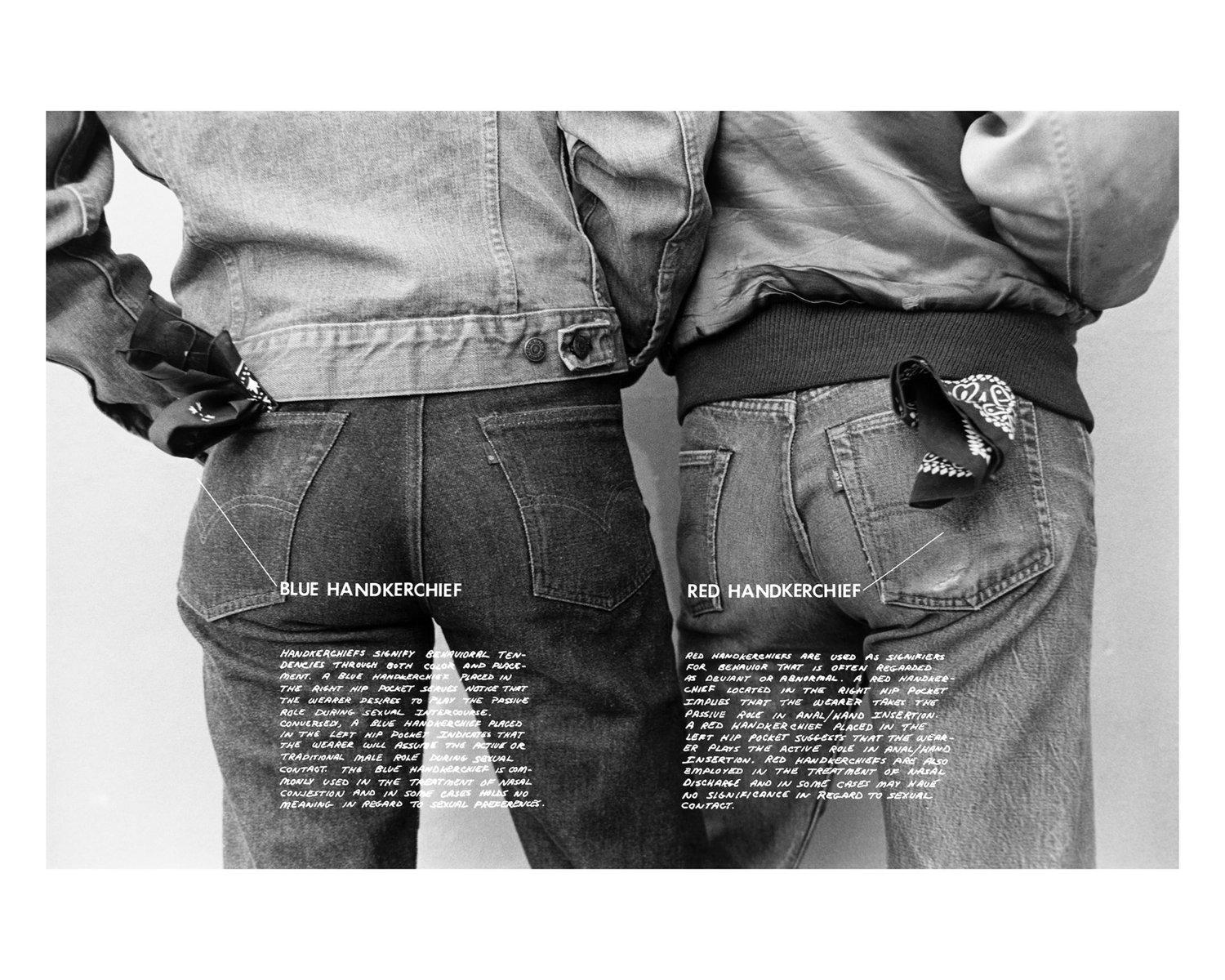

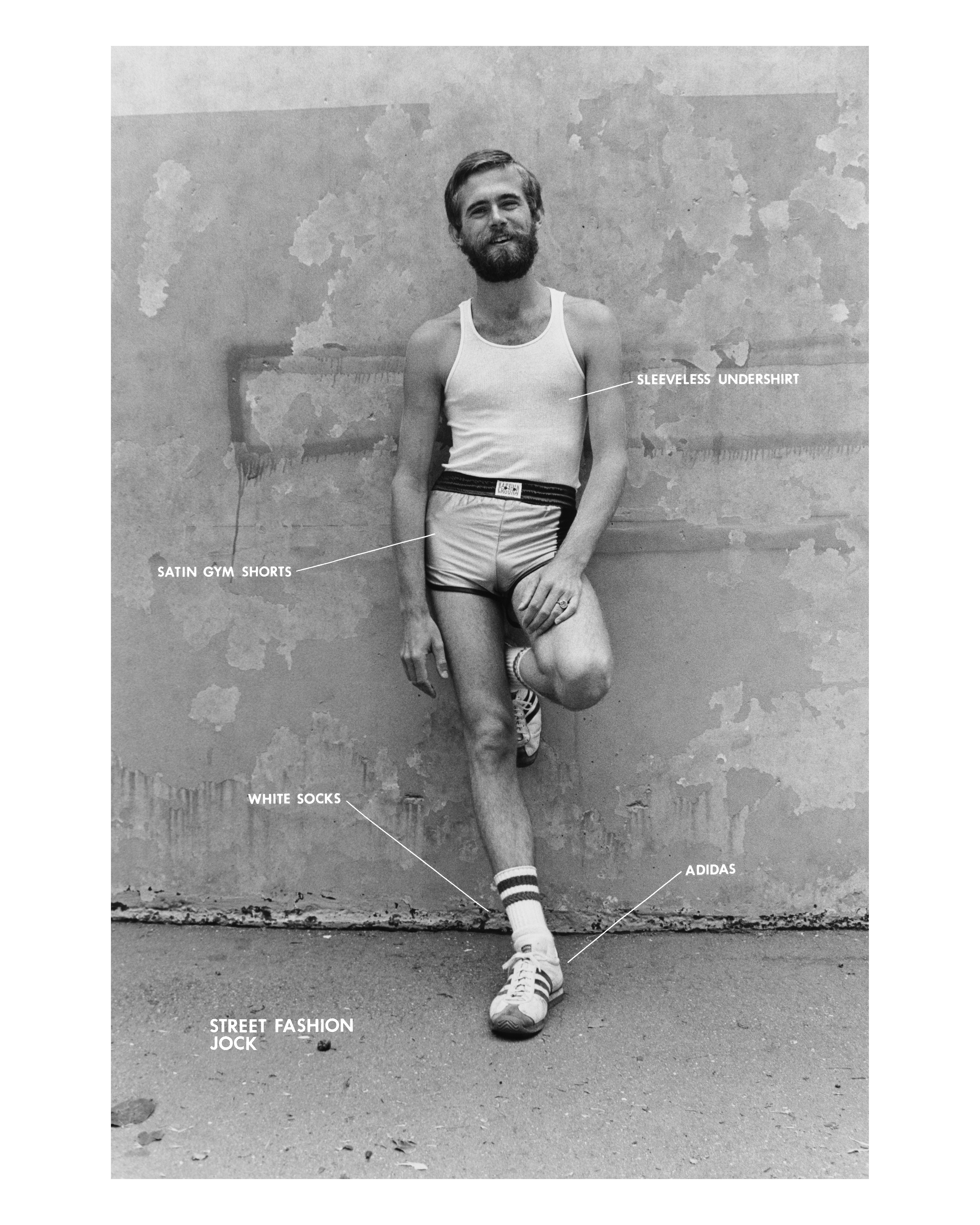

We begin our journey in San Francisco's Castro and Haight-Ashbury neighborhoods in the late 1970s. The streets are prowled by Jocks, Hippies, and Cowboys—or at least these are some of the street fashion styles and archetypes Hal Fischer (American, b. 1960) identified in his seminal Gay Semiotics series. The suite of 24 photographs decodes the signs and symbols Fischer's community of primarily gay white cisgender men used to discreetly signal their sexual interests. For example, in text handwritten over one of his photographs, Fischer noted that “a blue handkerchief placed in the right hip pocket serves notice that the wearer desires to play the passive role during sexual intercourse”—and conversely—“a blue handkerchief placed in the left hip pocket indicates that the wearer will assume the active or traditional male role during sexual contact.”

Thomas and Amos

Robert Mapplethorpe, Thomas and Amos, 1987.

Gelatin silver print; sheet: 24 × 20 in. (61 × 50 cm); framed: 33 1/8 × 28 1/2 × 2 in. (84.1 × 72.4 × 5.1 cm). Collection Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago, Gift from The Howard and Donna Stone Collection, 2002.43.

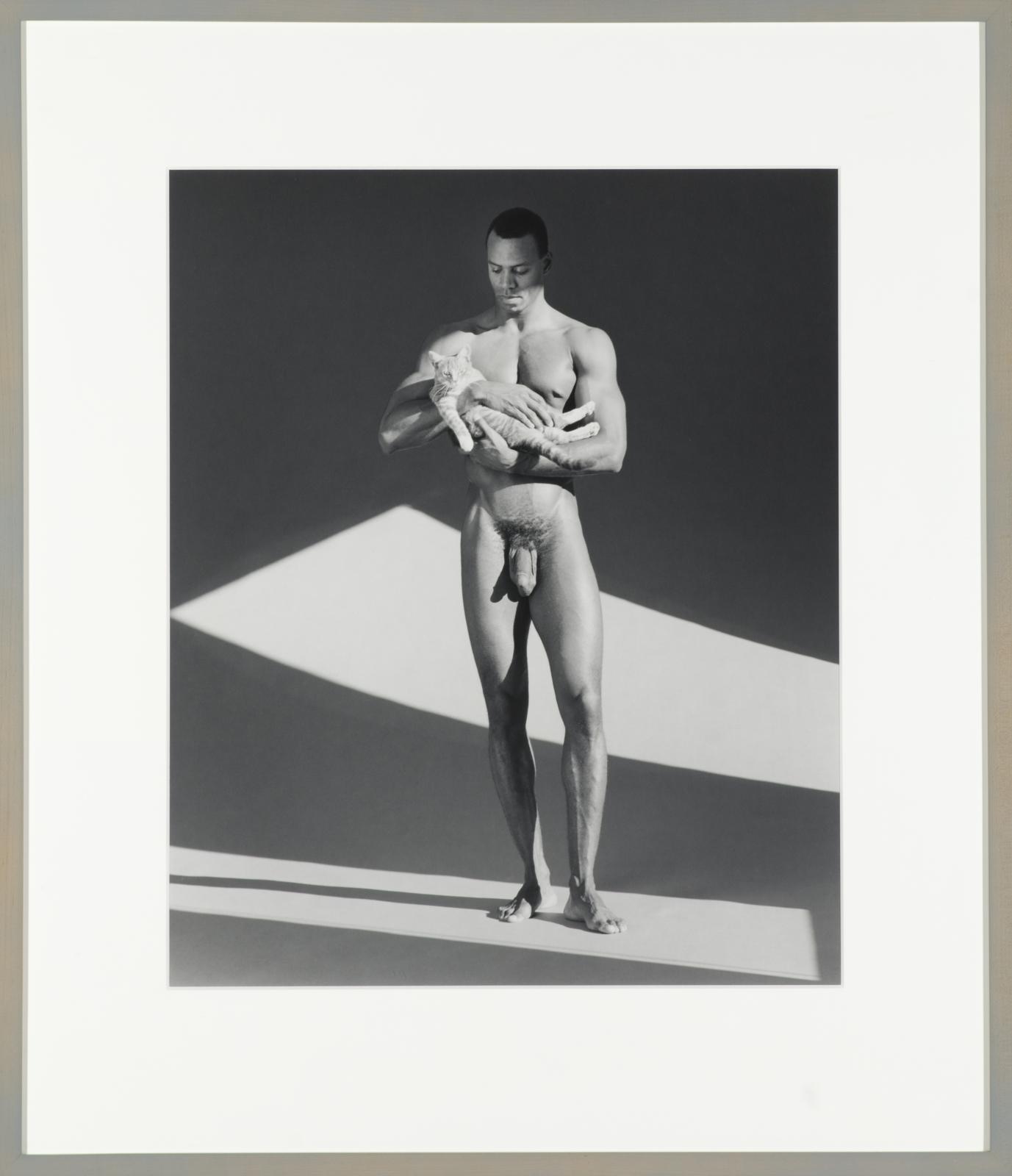

Flipping coasts—in the 1970s and 1980s Robert Mapplethorpe (American, 1946–1989) scandalized the art world with his photographs of subjects traditionally only visible in gay pornography. Mapplethorpe recruited his models in the leather bars and sex clubs he frequented in New York City. It's clear from his oeuvre that Mapplethorpe had a particular interest in Black men, such as the titular subject in his photograph Thomas and Amos (1987), with whom Mapplethorpe worked between 1986 and 1987. Thomas, who was Mapplethorpe's muse and lover, posed nude and statue-like in Mapplethorpe's studio with sunlight casting dramatic shadows on the set—as well as the model's anatomy.

Mapplethorpe intended for his images of Black men to be celebratory. However, he's been criticized for reifying harmful stereotypes of Black men in his images. Artist Isaac Julien (British, b. 1960) and historian Kobena Mercer wrote, “Mapplethorpe appropriates the conventions of porn's racialized codes of representation, and by abstracting its stereotypes into 'art,' he makes racism's phantasms of desire respectable.”[3]

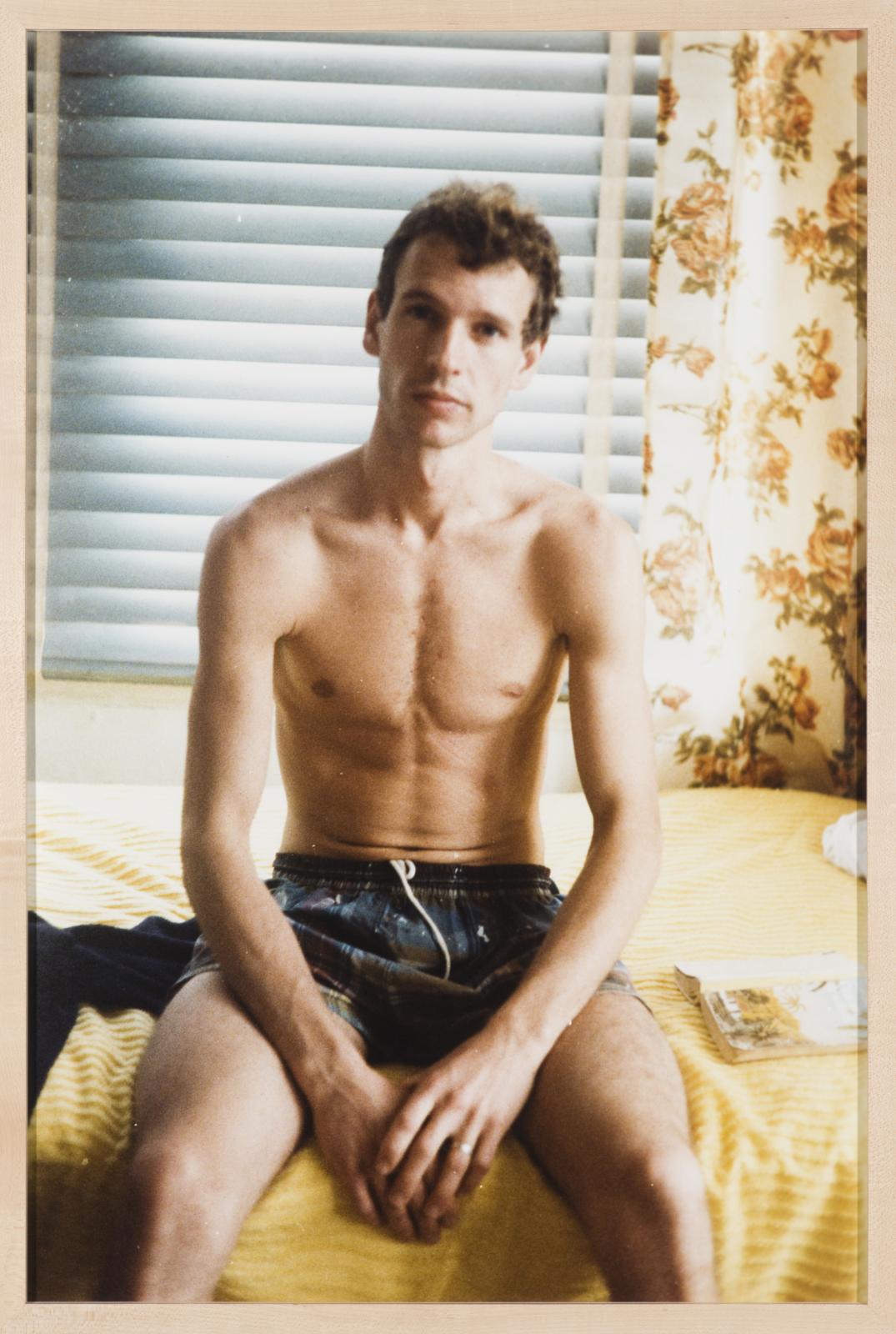

Angel Youth

Jack Pierson

The Call Back, 1995

Chromogenic development print; 30 × 20 in. (76.2 × 50.1 cm)

Collection Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago, Restricted gift of The Dave Hokin Foundation, 1995.119.1

Jack Pierson

Ocean Drive, 1985

Chromogenic development print; 30 × 20 in. (76.2 × 50.1 cm)

Collection Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago, Restricted gift of The Dave Hokin Foundation, 1995.119.6

Jack Pierson

Palm Springs, 1990

Chromogenic development print; 30 × 20 in. (76.2 × 50.1 cm)

Collection Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago, Restricted gift of The Dave Hokin Foundation, 1995.119.7

Similarly to Mapplethorpe, artist and fellow New Yorker Jack Pierson (American, b. 1960) often had relationships with his models. However, unlike Mapplethorpe, his subjects were more often friends and lovers first, and models second. At age 23, Pierson took a road trip from New York City to Florida, where he ended up broke and stranded for six months. During his accidental tropical furlough, Pierson began documenting casual encounters with friends and hookups, as well as the lush landscape of the region. Pierson's hazy photographs from his Angel Youth series—such as Palm Springs (1990), a poolside nude self-portrait of the young and gingery Pierson—capture the artist's wild and carefree twenties as he travelled across the US; from Miami to LA and back home to New York.

Joey at the Love Ball, NYC

Nan Goldin, Joey at the Love Ball, NYC, 1991

Chromogenic development print; framed: 31 7/8 × 44 5/8 in. (81 × 113.3 cm). Collection Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago, Gift of Anne D. Koch, 2014.45.

Photographer Nan Goldin (American, b. 1953) has a similarly diaristic practice; as she explains, “I don't select people in order to photograph them, I photograph directly from my life.”[4] In Joey at the Love Ball, NYC (1991) we see Goldin's friend and muse: the legendary drag queen Joey Gabriel, who also worked with Mapplethorpe. In the photo, Gabriel is dressed in full queer regalia on her way to the Love Ball II. Co-organized by nightlife icon Susanne Bartsch and ballroom legend Paris Dupree, the event brought together fashion designers, celebrities, and figures from the ballroom scene to raise money for people affected by the ongoing HIV/AIDS pandemic in the United States. Goldin's photograph vibrantly captures an individual's contribution to a collective history.

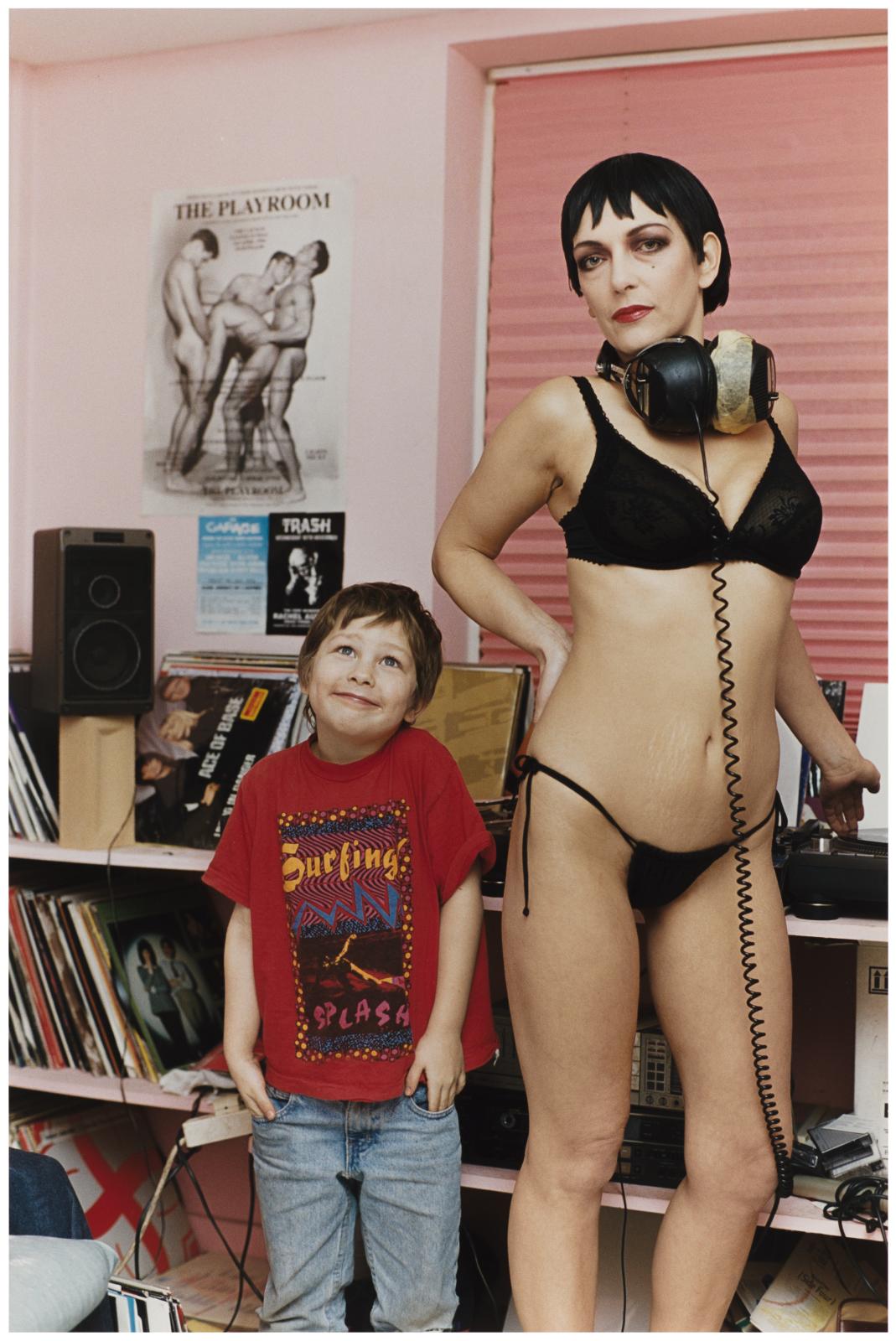

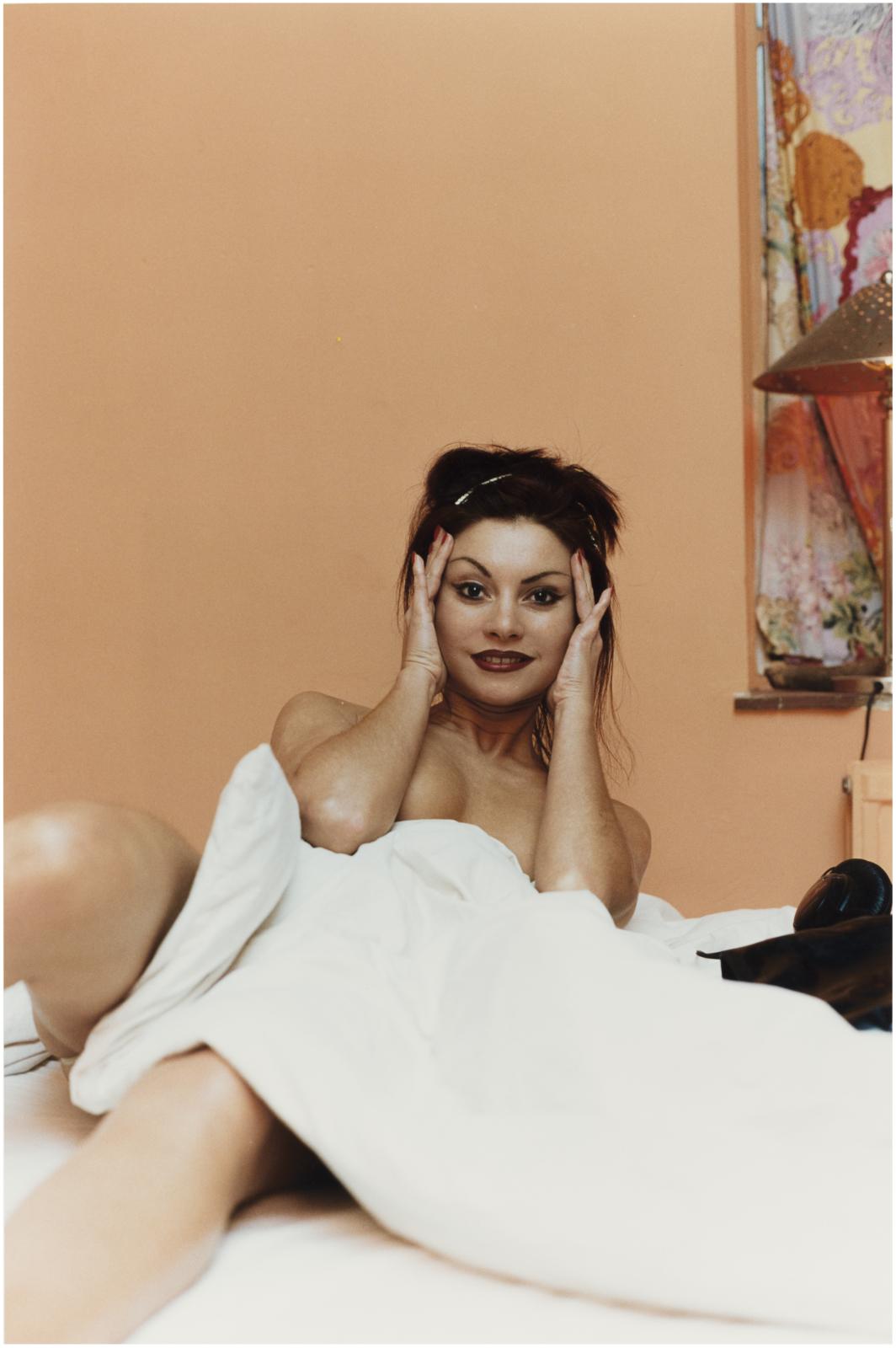

Princess Julia & Rachel Aubern

Wolfgang Tillmans

Rachel Auburn, 1995

Chromogenic development print; 22 × 15 in. (55.9 × 38.1 cm)

Collection Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago, Gift of Martin Fluhrer, 2011.49

Wolfgang Tillmans

Princess Julia, 1995

Chromogenic development print; 22 × 15 in. (55.9 × 38.1 cm)

Collection Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago, Gift of Martin Fluhrer, 2011.50

A few years later and across the pond, photographer Wolfgang Tillmans (German, b. 1968) created a series of portraits depicting London's premiere female DJs. The London club scene of the mid-90s was dominated by the sounds of acid house, and served as a refuge for queer people and other partygoers in an otherwise conservative political era. Tillmans's Princess Julia and Rachel Aubern (both 1995) are intimate images of each woman in her respective home. Notably, when the pictures were first printed in Andy Warhol's Interview magazine in 1995, “The Playroom” poster on Aubern's wall was censored.

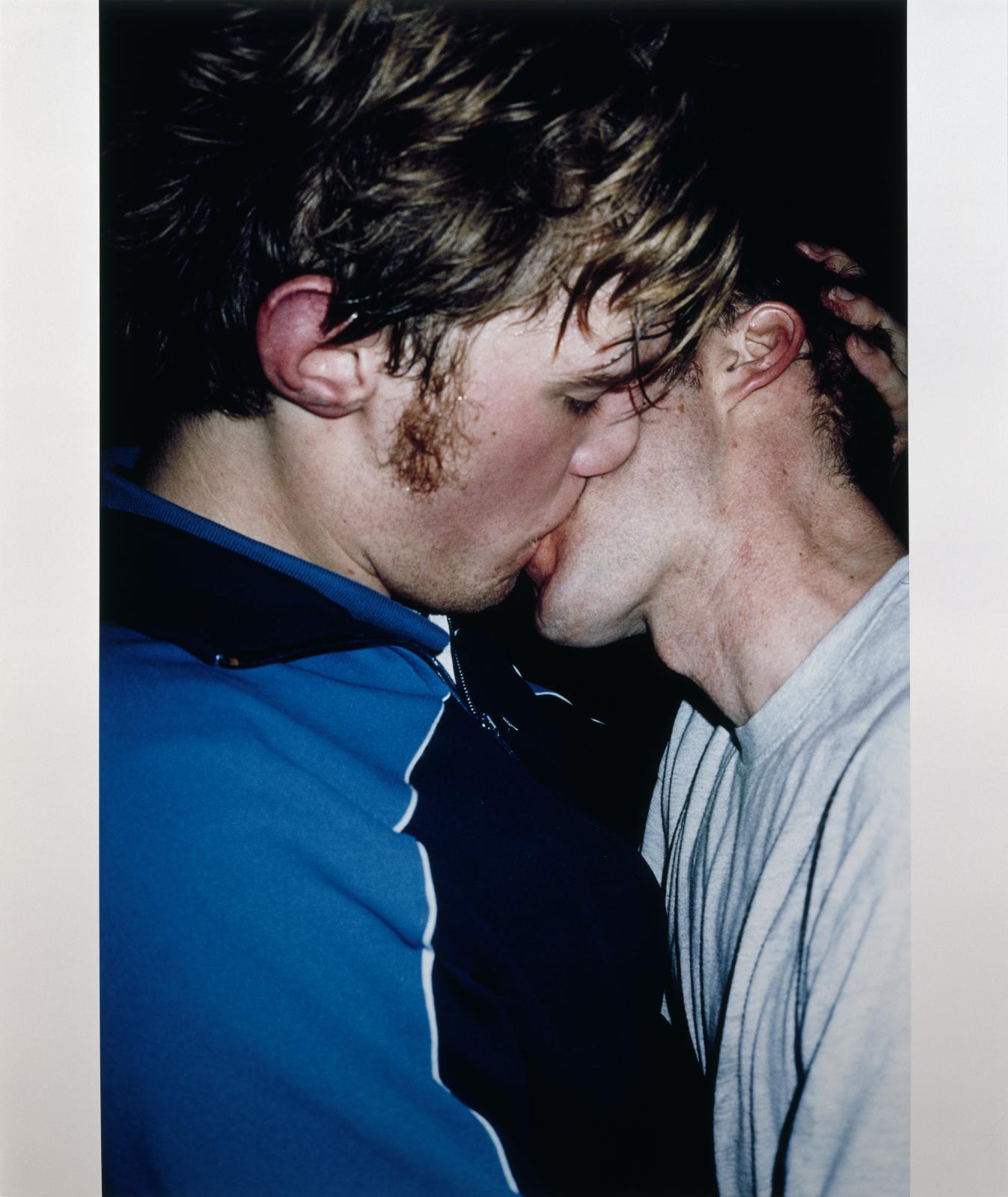

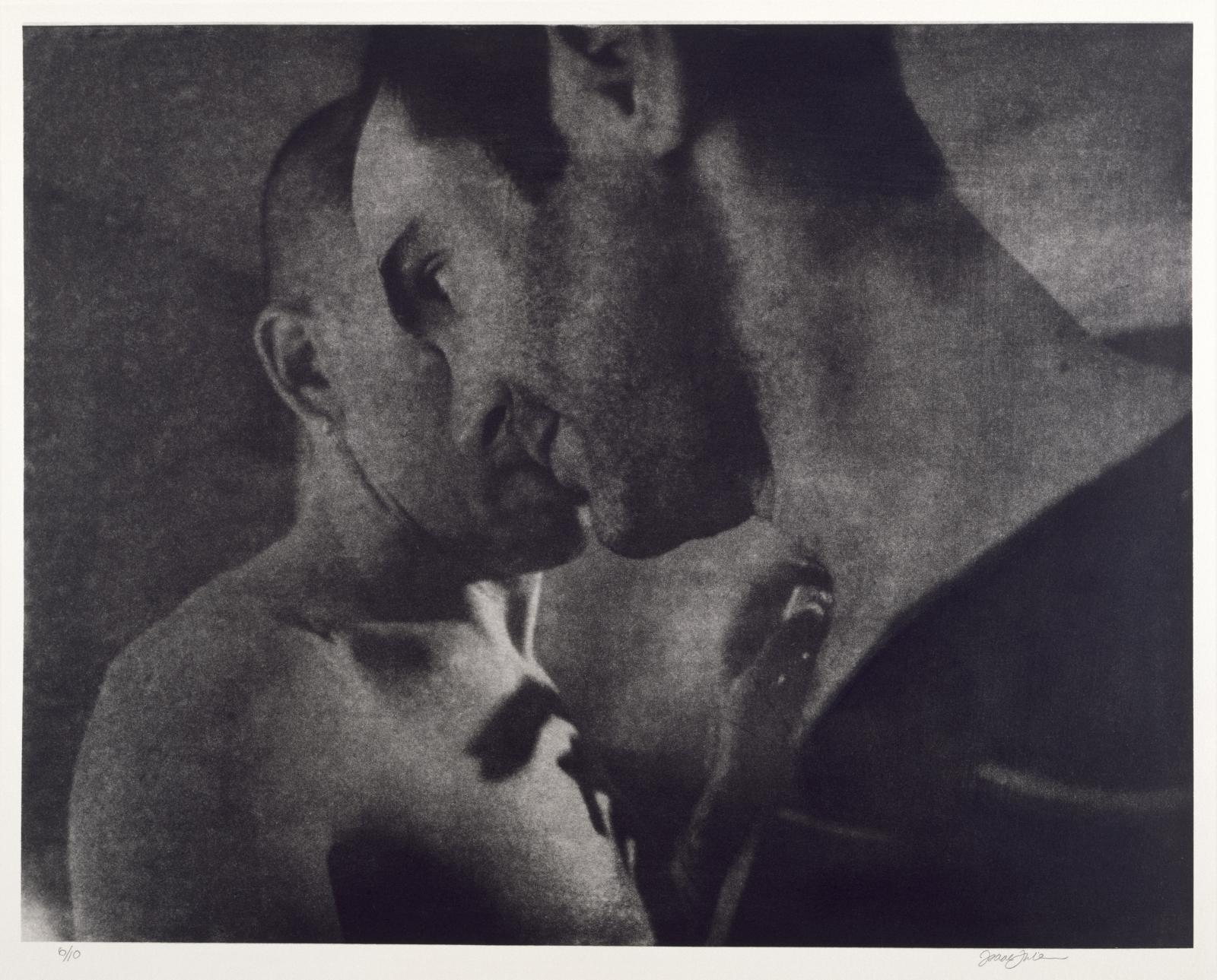

The Cock (Kiss)

Wolfgang Tillmans, The Cock (Kiss), 2002.

Chromogenic development print; 24 × 20 1/8 in. (61 × 51.1 cm). Collection Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago, Joseph and Jory Shapiro Fund by exchange, 2006.15.

Many of Wolfgang Tillmans's iconic images come from the artist's engagement with the London club scene. The Cock (Kiss) (2002) was shot during the queer electroclash party of the same name at The Ghetto, a club in central London. Apart from its visceral beauty, the image gained notoriety for being slashed and vandalized while on view at the Hirshhorn Museum in Washington, DC. Speaking on the incident, Tillmans said, “Beauty is of course always political, as it describes what is acceptable or desirable in society. That is never fixed, and always needs reaffirming and defending.”[5] The Cock (Kiss) was also shared widely on social media in the wake of the Pulse nightclub attack in 2016. In the attack, 49 people (many of whom were queer clubgoers) were massacred in Orlando by a young man who had reportedly become enraged at the sight of two men kissing at a bar in Miami the week prior. By lending visibility to the subcultural activities of queer people, Tillmans—like all of the artists discussed here—does the vital work of normalizing queer life for a broader audience.

After Mazaltan

Isaac Julien, After Mazatlan, 1999/2000.

Black-and-white photogravure on Arches paper; 22 × 30 in. (55.9 × 76.2 cm). Collection Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago, Gift from The Howard and Donna Stone Collection, 2002.37.

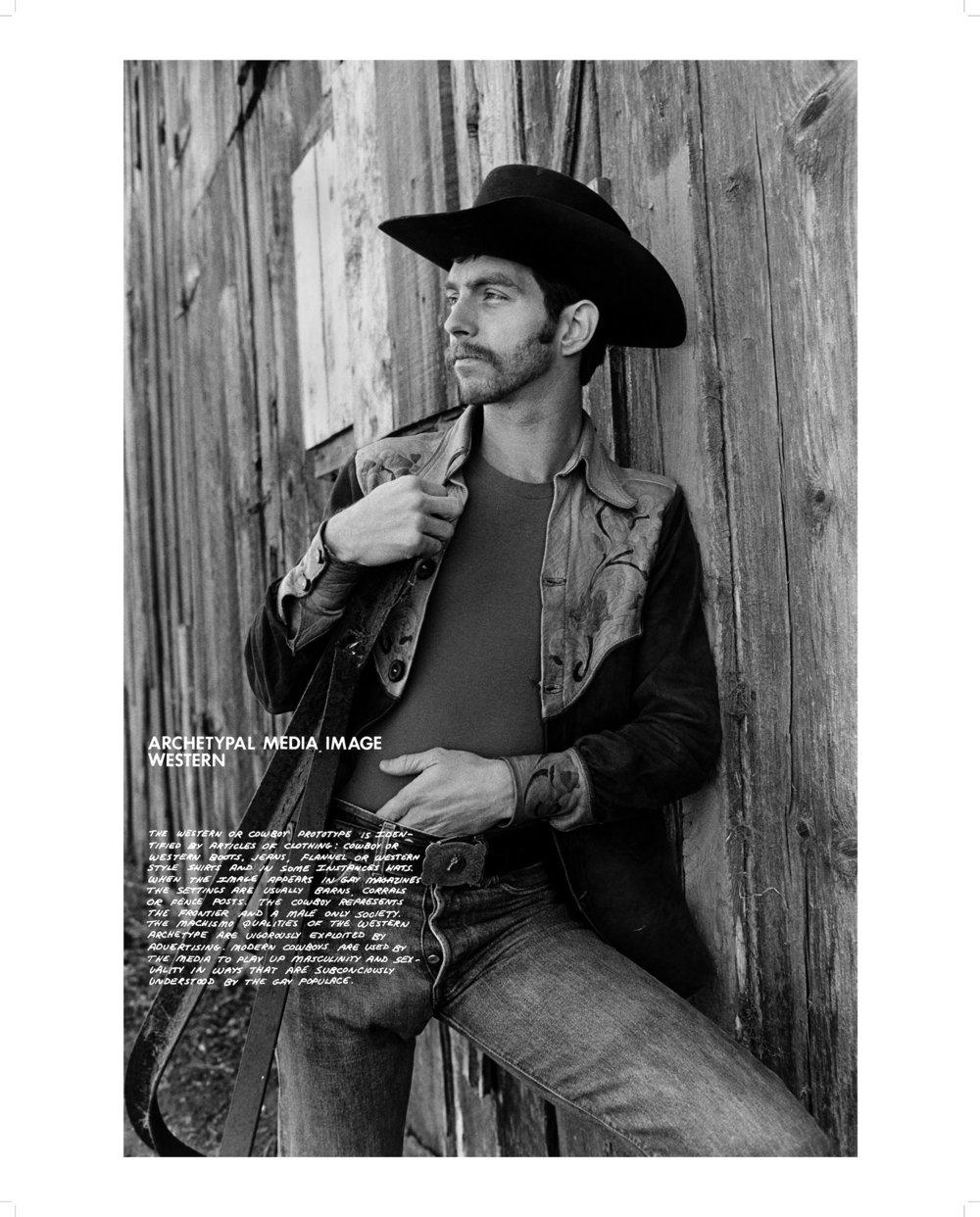

Back stateside—After Mazaltan (1999/2000) is a photographic print by artist Isaac Julien (British, b. 1960), made while he shot his three-channel video The Long Road to Mazeltan (1999) in and around San Antonio, Texas. Created in collaboration with choreographer Javier de Frutos (Venezuelan, b. 1963), the video work explores the iconography of the American Southwest. Specifically, Julien examined the cowboy as both a symbol of hyper-masculinity popularized by Hollywood and a gay subcultural archetype. In the film and photograph alike, two cowboys—one of which is played by de Frutos—engage in a homoerotic dance of glances, destabilizing both the pop-cultural and queer readings of the figure. As with all of Julien's films, Mazatlan challenges the racial and sexual stereotypes present in popular media.

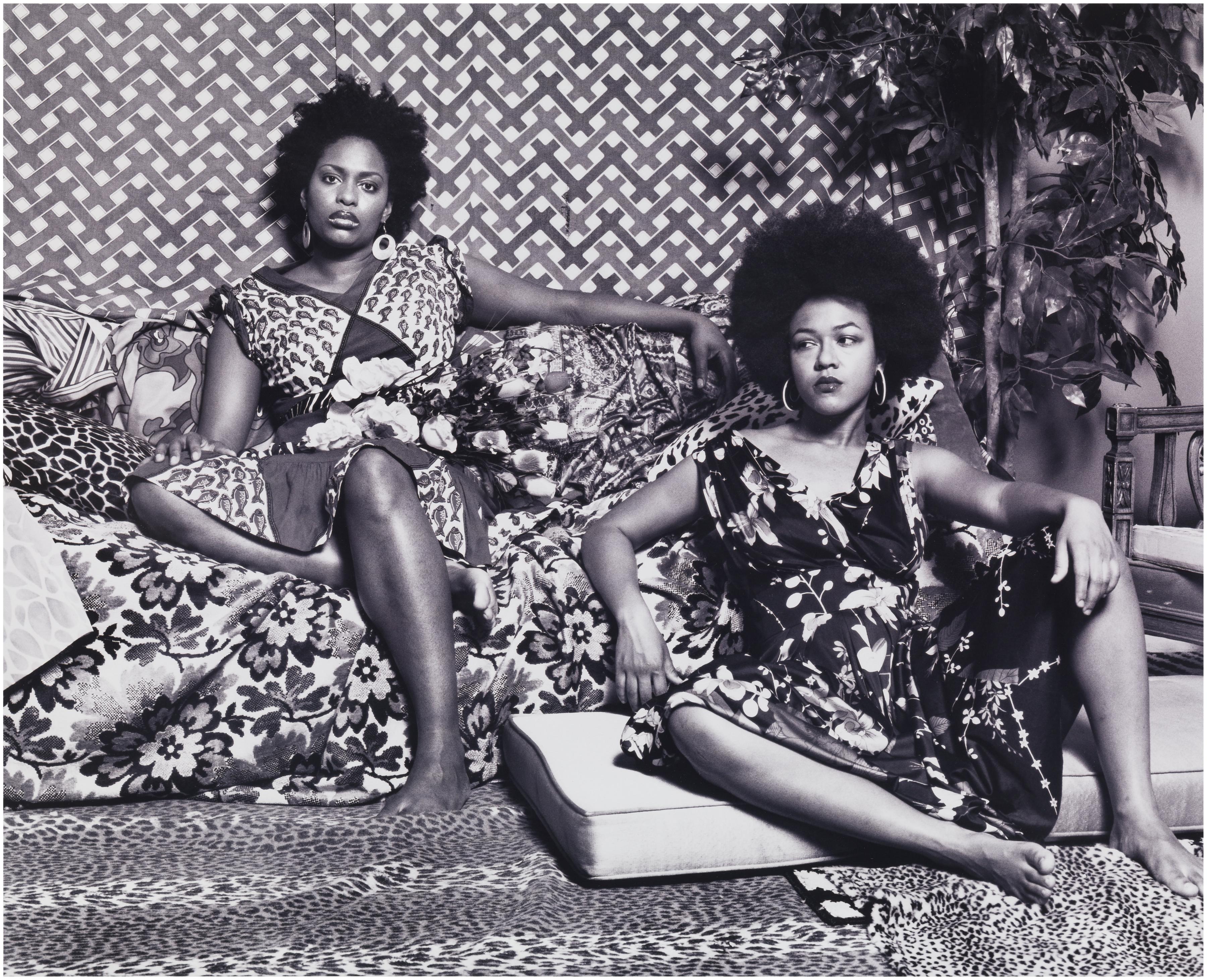

A Moment’s Pleasure

Mickalene Thomas, A Moment’s Pleasure, 2006.

Black-and-white print; framed: 17 3/16 × 21 1/8 in. (43.7 × 53.7 cm). Gift of Jack and Sandra Guthman.

Another artist working through the intersections of race and sexuality is Mickalene Thomas (American, b. 1971), who is best known for her elaborately layered collages and empowering images of Black women. Portraits such as A Moment’s Pleasure (2006) are staged against graphic backdrops of reupholstered furniture, rugs, and textiles reminiscent of her collages. Thomas works with a close circle of muses to create her images, including friends, lovers, her mother, and her partner Racquel Chevremont. Thomas says, “I like to think of the portraits as mirrors . . . We are not validated until we see ourselves, and the mirror is a tangible object that works as an evidence to external appearance. Not only are we present, we demand that we be seen, be heard, and be acknowledged.”[6] Thomas's work firmly establishes representation of queer women of color in the art-historical canon.

Mishima in Mexico

Wu Tsang, still from Mishima in Mexico, 2012.

High-definition video projection (color, sound) and programmed LED light installation, unique. Collection Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago, restricted gift of the Buddy Taub Foundation, 2013.35. © 2012 Wu Tsang.

Wu Tsang's (American, b. 1982) video Mishima in Mexico tells the story of a pair of actor-screenwriters attempting to adapt queer novelist Yukio Mishima's book The Thirst For Love (1950) into a Mexican telenovela. The meta-narrative sees Tsang and his collaborator Alexandro Segade (American, b.1973) shifting between each of the four characters. We see them writing the film's script in their room at the Camino Real Hotel in Mexico City and enacting scenes as if conducting screen tests. In one scene Segade deadpans, “It's so gay.” Tsang replies, “I wouldn't say gay, maybe queer.” Segade responds, “So Japanese”; to which Tsang rejoinders, “That's why we're in Mexico.” The film moves through cultural references with the same irreverence and fluidity with which gender is treated in the film. Mishima in Mexico crosses boundaries between culture, sexuality, and gender with such frequency as to render moot all of these markers of identity.

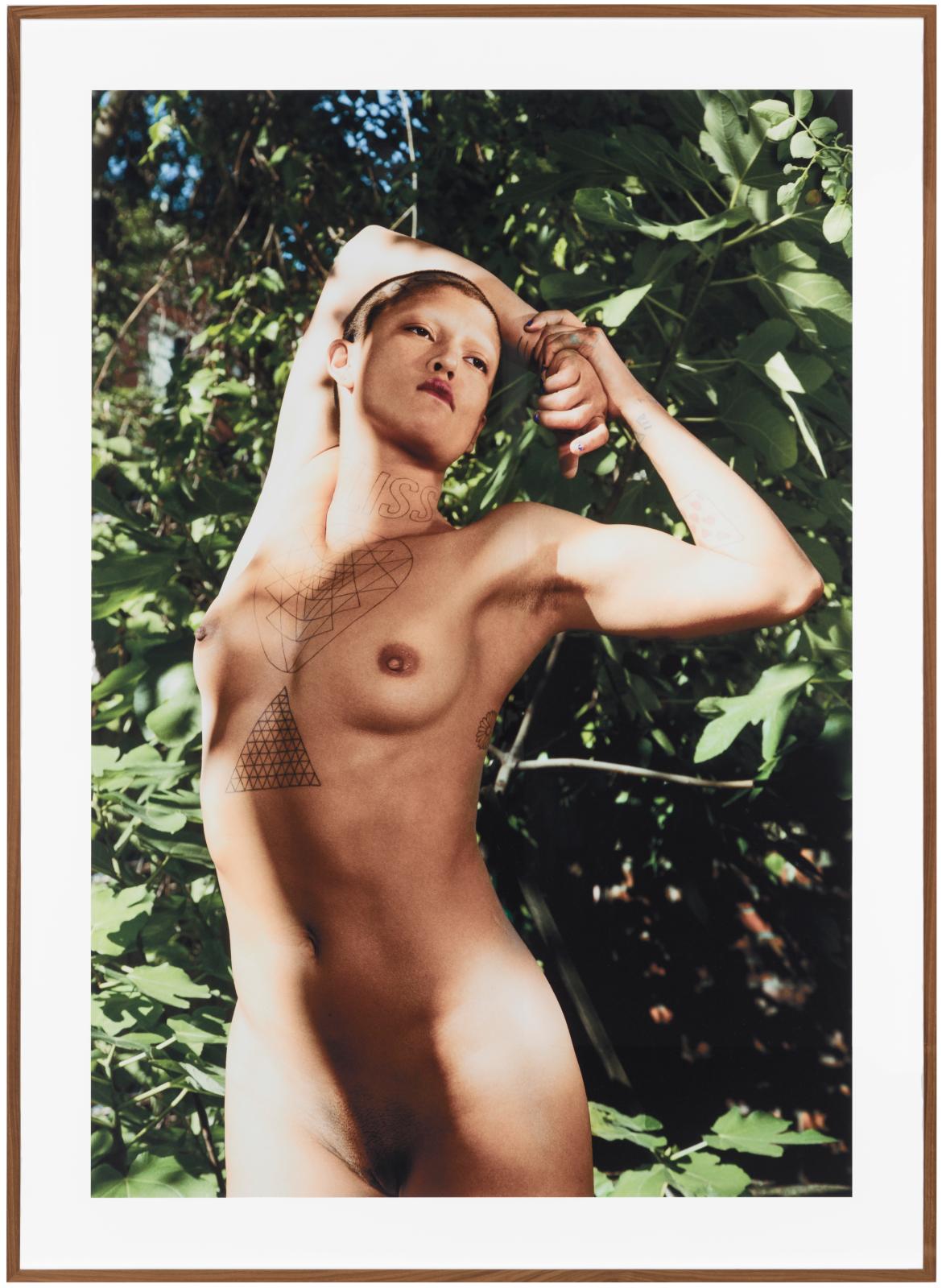

Where are you Going?

Collier Schorr, Where are you Going?, 2013.

Pigment print; sheet: 60 1/4 × 41 1/2 in. (153 × 105.4 cm); framed: 69 1/2 × 50 1/2 in. (176.5 × 128.3 cm). Collection Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago, Gift of Mary and Earle Ludgin by exchange, 2014.39.

Collier Schorr (American, b. 1963) is concerned with the problematic way in which women are “packaged and sold back to women” in popular culture. Throughout her career, Schorr rarely photographed women, tending instead to flip the script on the storied “male gaze” by selecting epicene young men as her models. [7] More recently, Schorr saw “power in taking back the ability to represent femininity as a multi-layered identity.” [8] Her photograph Where are you Going? (2013) portrays transgender performing artist boychild. [9] Schorr says, “I don't think men can take the kinds of pictures I take,” because subjects act differently in the presence of men. For Schorr the macrocosmic gender politics of society are always already present in the microcosmic, political space of the photoshoot.

Darkroom

Paul Mpagi Sepuya, Darkroom (1990407), 2017.

Archival pigment print. Collection Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago, gift of Mary and Earle Ludgin by exchange, 2018.25.

Paul Mpagi Sepuya (American, b. 1982) also questions the politics of the photoshoot. His work expands upon histories of queer studio portraiture by artists such as Mapplethorpe. Sepuya's images deconstruct the photoshoot by both revealing the mechanics of photography—the camera, tripod, and set—and unsettling the traditional relationship between artist, subject, and viewer. At first glance, Darkroom (_1990407) (2017) seems like a conventional self-portrait, but upon closer inspection, it becomes apparent that the image of the artist is actually a fragment of a photograph that was taped to a mirror and then rephotographed. Sepuya's photography reflects on the ways identity is constructed and obscured through representation.

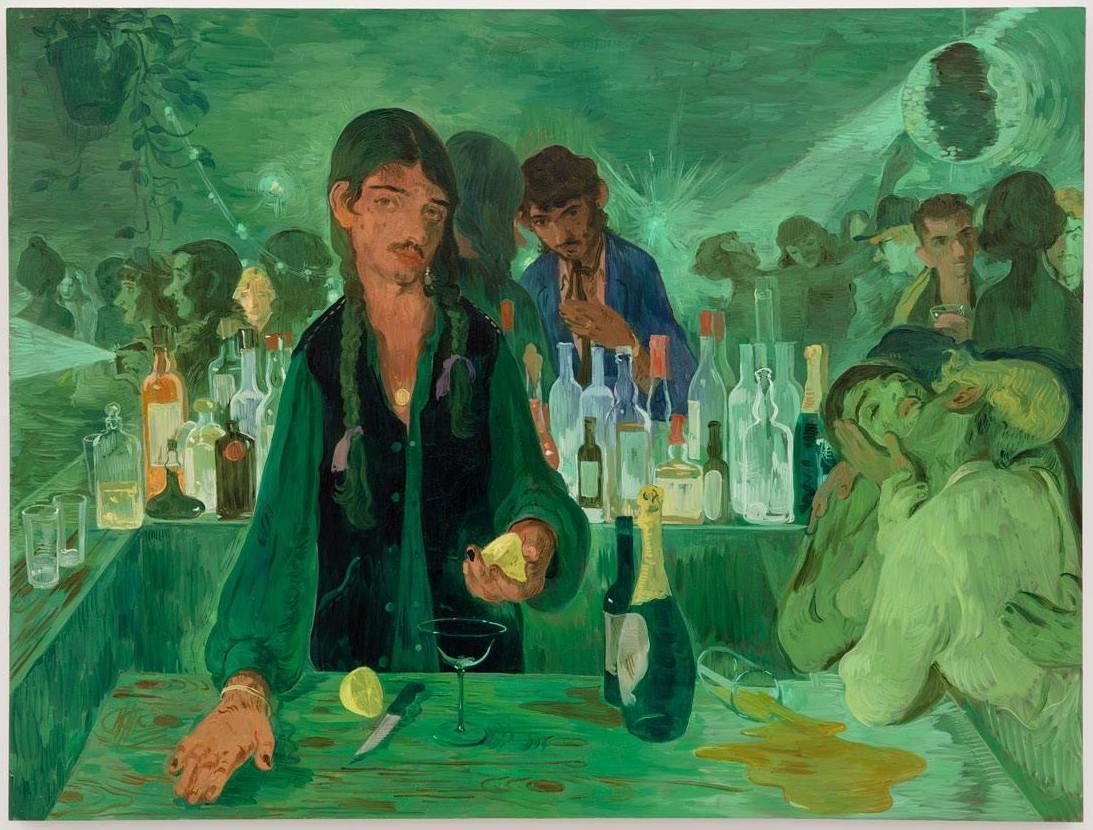

The Bar on East 13th Street

Salman Toor, The Bar on East 13th Street, 2019.

Oil on panel. Collection Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago, promised gift of Keith Fox and Tom Keyes, PG2019.3.

We conclude our cruise at the club. Salman Toor's (b. Lahore, Pakistan 1985) painting The Bar on East 13th Street (2019) is an homage to and subversion of Édouard Manet's (French, b. 1983) A Bar at the Folies-Bergère (1882). Manet's painting depicts a late–19th-century bar filled with patrons politely imbibing beneath crystal chandeliers. In contrast, Toor's painting depicts a raucous nightclub replete with queers enjoying each other's company under a shining disco ball. The subject of Manet's painting is a demure barmaid submitting to the gaze of a male patron seen in the reflection of a mirror behind the bar. In Toor's painting, a genderqueer bartender pauses while crafting a cocktail to meet the gaze of a patron while extending an inviting, manicured hand.

Manet and Toor’s paintings reveal a gulf between the gender politics of the 19th century and today, and all of the aforementioned images are glimpses into a timeline of shifting cultural attitudes towards LGBTQ+ people. While we celebrate Pride this month, we recognize how far we’ve come—but only in tandem with an understanding that our work is not done. Trans and gender non-confirming people, as well as Black, Indigenous, and people of color, continue to face systemic financial, carceral, and interpersonal oppression.

The LGBTQ+ community knows better than most that collective action is the only path to change. Some of us may still be confined to our homes because of the COVID-19 pandemic, others may already be out in the streets in solidarity with #blacklivesmatter—either way, this month we can show our Pride by doing everything we can to support the Black Lives Matter and Black Trans Lives Matter movements.

_________________________________________________________________________________________________________

[1] In addition to George Floyd, protestors were catalyzed by the recent high-profile murders of Breonna Taylor by the Louisville Police Department and Ahmaud Arbery by white vigilantes.

[2] According to the 2019 ILGA World State-Sponsored Homophobia report, being LGBTQ+ is still criminalized to varying degrees in 70 countries.

[3] Mercer, Kobena, “Black Masculinity and the Sexual Politics of Race: True Confessions: A Discourse on Images of Black Male Sexuality with Isaac Julien” in Kobena Mercer, Welcome to the Jungle: New Positions in Black Cultural Studies (New York: Routledge, 1994).

[4] Nan Goldin, The Ballad of Sexual Dependency (New York, NY: Aperture Foundation, 1986).

[5] Wolfgang Tillmans, "Wolfgang Tillmans and His (Almost) All Consuming Eye," AMERICAN SUBURB X, May 18, 2020, https://americansuburbx.com/2015/07/wolfgang-tillmans-lecture-2011.html.

[6] Patricia Martin, "Mickalene Thomas: Layers of Black Womanhood through an Artist's Eyes," The Glam Femme, May 15, 2019, https://www.theglamfemme.com/mickalene-thomas-layers-of-black-womanhood-through-an-artists-eyes/.

[7] Francesca Gavin, "Collier Schorr: Still Chasing the First High," Dazed, February 24, 2014, https://www.dazeddigital.com/fashion/article/18446/1/collier-schorrs-androgynous-youth.

[8] Gavin.

[9] boychild is Wu Tsang's partner and frequent collaborator. The pair presented Moved by the Motion on the MCA stage in 2014.