Kenneth Josephson

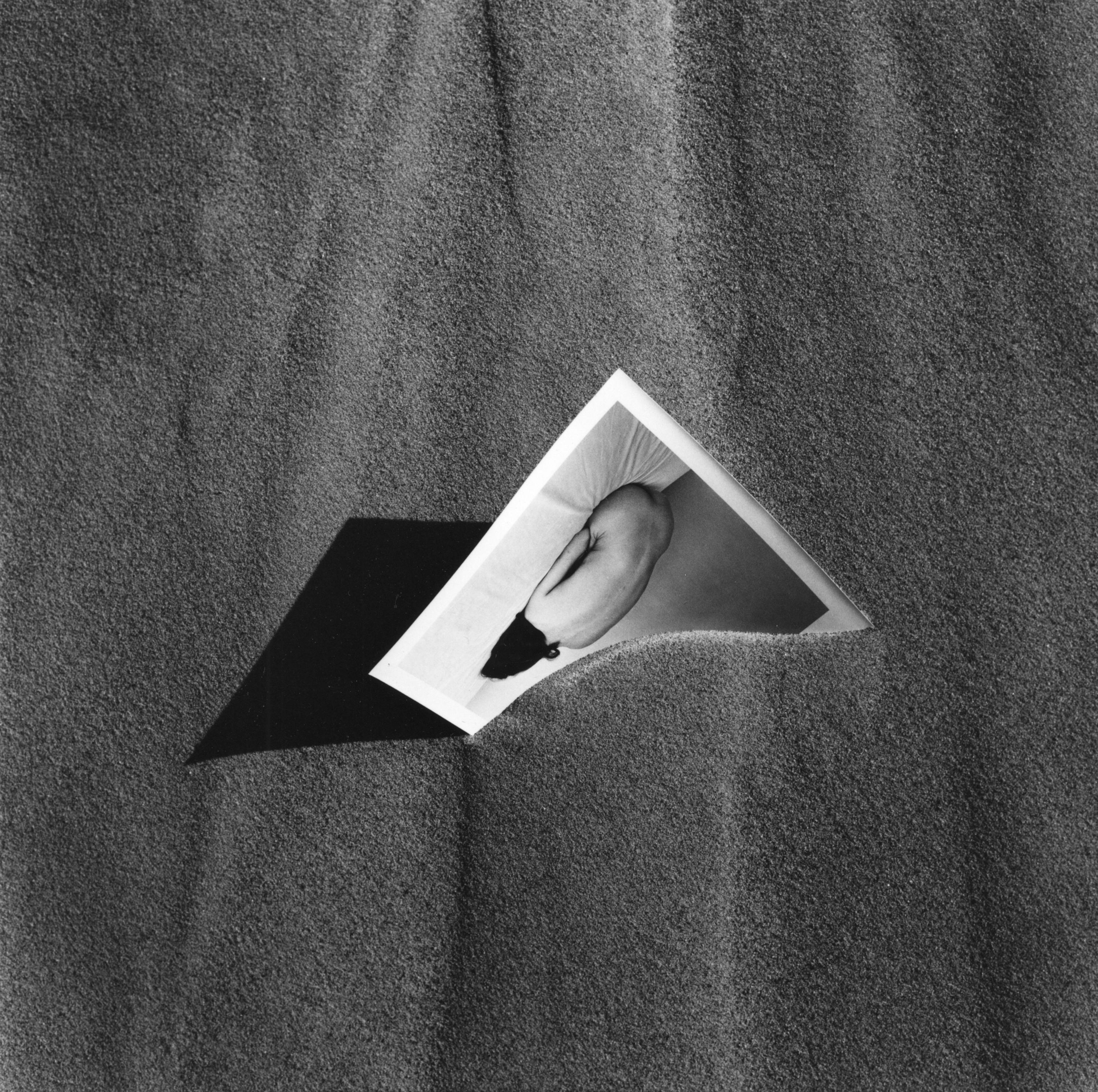

Kenneth Josephson, Chicago, 1973, 1973. Gelatin silver print; 6 1/32 x 9 1/16 in. (15.3 x 23 cm). Courtesy of the artist and Stephen Daiter Gallery, Chicago

Kenneth Josephson by Lynne Warren

Chance favors the prepared mind.

—Louis Pasteur

KENNETH JOSEPHSON IS TALL, and in his ninth decade still stands straight. He has worn his hair long and tied back for years even as it has thinned and turned white. His gaze is steady, and often holds a slant of inquiry, as if he's thinking deeply while he listens, and even more deeply while he speaks in his soft, deliberate voice with the flat tones of his midwestern heritage. He favors cowboy boots and hats; some of his self-portraits show his behatted shadow.[[1]](#ref-1)

While I have known Josephson for over forty years, and he is friendly and open, there is an essential mystery about him, as there is about any true artist. I have long known of his Detroit origins and the path to his art form: a childhood interest that caused him to pursue an education as a commercial photographer at the Rochester Institute of Technology, followed by his enrollment in the now-legendary graduate program at Chicago's Institute of Design (ID).[[2]](#ref-2) With Josephson in his eighties, still vital and still making photographs, contemplating his journey to success as a seminal, world-renowned photographer evokes faraway and perhaps mysterious times and places, especially for his younger admirers, bred as they are on digital photography shaped by the conceptualism that Josephson in large part brought to the medium. For those of us who are longtime admirers, Josephson's story, given that he emerged in an era of limited choices and significant barriers to establishing a life in the arts, has a bracing, optimistic quality.

What was it to be interested in photography coming up in Detroit in the 1950s? The city, at that time, was a potent symbol of American know-how and industrial might but hardly a cultural powerhouse, although it had produced one of the twentieth century's most extraordinary artists in Josephson's mentor, Harry Callahan.[[3]](#ref-3) As a boy, Josephson had recognized how "wonderful"—to use his own word—it was to shoot and print photographs in his own darkroom. Pursuing his interest in photography, he attended the only photography school he'd then heard about, the Rochester Institute of Technology (RIT) in upstate New York.[[4]](#ref-4) At the time of Josephson's attendance, RIT offered only a two-year program. Upon graduating with an associate's degree in applied science, he was drafted into the army and spent much of the obligatory two years working in a darkroom in Germany. It was mere happenstance that, during the period of Josephson's military service, RIT's offerings in photographic education expanded to include a four-year degree program that featured on its faculty such well-known fine-arts photographers as Minor White. This development drew Josephson back to Rochester, and it was from the contacts made in Rochester the second time around that Josephson heard about ID.[[5]](#ref-5) Armed with RIT's newly bestowed bachelor's degree, he was able to be admitted to the only graduate program in fine arts photography in the United States. He relocated to Chicago, where he thrived under the tutelage of instructors Callahan and Aaron Siskind, and obtained his MS in 1960, becoming part of the famous "Chicago School.” The G.I. Bill—a benefit afforded by his service in the army—had allowed Josephson to pursue an unlikely career for a man of his time: fine-arts photographer.[[6]](#ref-6) Not only was he entirely successful in that pursuit, as evidenced by his outstanding international career, he was also a pathfinder for another unlikely vocation, that of professor of photography. After founding the photography department at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago (SAIC) in 1961, he taught there for thirty-seven years.[[7]](#ref-7)

Contemplating this chain of events, it is not surprising to learn that Josephson is drawn to the words of the scientist Louis Pasteur: Chance favors the prepared mind. He cites this concept as a guiding principle for his life and art, and on the matter of how he works, Josephson is absolutely clear: “The idea is most important. . . . I 'make,' not take, photographs."[[8]](#ref-8)

Despite all the change Josephson has seen during his lifetime, in the world and in his field, he still uses film and develops photos in his own darkroom. And even a cursory overview of his formidable oeuvre reveals his dedication to making photographs that accurately describe but at the same time intrigue; photographs that capture the world but cannot be said to document it; images that please the eye while exciting the brain. This cerebral approach of “making, not taking” photographs casts Josephson as one of the first conceptual photographers. He is an artist who creates photographs that are best understood by acknowledging and exploring the ideas presented by the images. Yet, despite being idea-driven, the images are visually interesting and often exquisite in their composition, tonality, and clarity.

Even when Josephson was producing photographs that are today classified as street photography, a genre seen as occupying many who studied at ID in the 1950s, it is clear that the ideas behind the making of the images were predominant. His ID training, like that of his fellow students—Joseph Sterling, Yasuhiro Ishimoto, Joseph Jachna, Ray Metzker, and Charles Swedlund[[9]](#ref-9)—centered on the exploration of techniques (such as in-camera multiple exposure) and themes (such as city life). At sixty years' remove, there is an undeniable fond nostalgia for the inky blacks and shrapnel whites of street photography, in which the gloom and grit and bleak anonymity of the midcentury industrial city are preserved, shrouding in shadow people with masklike, expressionless faces or illuminating them with harsh light. But these photographs speak of more than romance for a bygone era. They also speak of the demographic of Josephson's generation: postwar, mostly male, and seeking a very different vision than the precision of the f/64 school, as typified by the early-twentieth-century masters Ansel Adams and Edward Weston. Fame was never a consideration for the photographers making their way in the 1950s, because fine-arts photography was a rarefied field and few made a living at it unless they taught or did commercial studio work on the side. Although Josephson's work clearly shares formal similarities with that of many of his ID contemporaries, even at this early stage in his development he was not merely documenting his surroundings. His images were not only carefully crafted, but carefully thought out.

At this time in his career Josephson alternated between the example of his teacher, Harry Callahan, who experimented with light and multiple imagery and sensitively photographed the city and its people—including his wife and daughter—and the example of Aaron Siskind, who is best known for pulling the urbanscape in for close-ups of peeling paint, walls layered with posters, graffiti, and grime.[[10]](#ref-10) Like most of his peers, Josephson set out into the city and made pictures of seemingly meager circumstances: people under the El, boys playing on piles of rubble. But they are also beautiful and sensitive pictures, personal in a way that the great mountain ranges and elegantly posed nudes of his f/64 school predecessors are not. By the late 1950s, however, as the economic growth of the postwar era offered stability and more options for a rapidly growing, consumerist middle class, opportunities emerged for artists to both make a living and make a difference in the visual culture. The photo community, though it remained small and tightly knit, was beginning to feel the urgent necessity of change.

But for the moment, the world as pictured by Josephson was still dark, with an elegiac, closed-in quality. One of his early masterpieces is the poetic Chicago, 1961. This photograph shows a Callahan-esque frieze of bodies under Chicago's famous El. The poses of the subjects and rhythms of this photograph are so astonishing that it is hard to believe the figures weren't posed or choreographed, but they were not. The picture, a masterful melding of the photographer's attuned eye and the chance occurrences that continually occur, demonstrates Josephson's method. This "eye" is evident in the precise geometry of the lines of the pavement and the streaks of sunlight on it: the central vertical line falls virtually in the center of the image as it joins the black band that runs across the image's lower edge. The chance occurrences of the world are represented by the "spotlight" that falls on the two men and two women: that is, the strong summer sunlight penetrating the deep shadows of the iron and wood structure of the elevated tracks and platforms and highlighting the perfect, balanced posture of the woman on the left; the graceful arc of the man's body on the right; and the man in the midstride, swinging by the woman in the center whose stance is a less composed reflection of the poise displayed by her female counterpart. And then there is that astonishing bit of frivolity on the back of the man at the right as the sunlight illuminates a vertical pattern on his shirt fabric. This isn't the magic of the darkroom, this is eye magic.

Given the immense poetry of an image such as Chicago, 1961, the matter-of-fact way that Josephson has spoken about the making of these works can be startling. In his early years of employment at the School of the Art Institute—Josephson was hired shortly after obtaining his degree from ID on the strength of his graduate thesis—he was kept quite busy by his classes. But, dutiful to both his job and his craft, Josephson used his lunch breaks and his moments before heading home to expose film. SAIC is situated just east of that area of downtown Chicago called the Loop, so named because it is encircled by the elevated train. The structure that provided a visual environment so appealing to Josephson—his beautiful images made under the El belie the hectic pedestrian traffic, the ear-splitting noise of bare metal on metal, and the often overwhelming pigeon filth—was a convenient five-minute walk from his workplace. It was also a familiar environment in which he was comfortable. The Institute of Design, where he had spent the previous two years, was located near the El tracks on Chicago's near-south side.[[11]](#ref-11) Furthermore, the theme of bodies struck by light was an important aspect of "An Exploration of the Multiple Image," the thesis Josephson had submitted in June 1960 as a requisite for receiving his master's degree.[[12]](#ref-12) In the thesis, an in-camera multiple exposure of children jumping titled Chicago, 1960 shows wildly distorted black shadows. These were cast by the nearby El tracks (now known as the “Red Line"), falling across the steep sandy mounds of a vacant lot across the street from ID.[[13]](#ref-13) Another version of this image is Chicago, 1960, which is not a multiple exposure and which more clearly shows the boys in winter coats gleefully clambering up, and then throwing themselves off, the hillocks. The boy silhouetted against the horizon line of the mounds eerily recalls Robert Capa's famous "The Falling Soldier" (Loyalist Militiaman at the Moment of Death, Cerro Muriano, September 5, 1936). But a photographic reference much closer to home would be Aaron Siskind's renowned body of work, Pleasures and Terrors of Levitation, the series of men caught in midair that he undertook between 1953 and the mid-1960s.

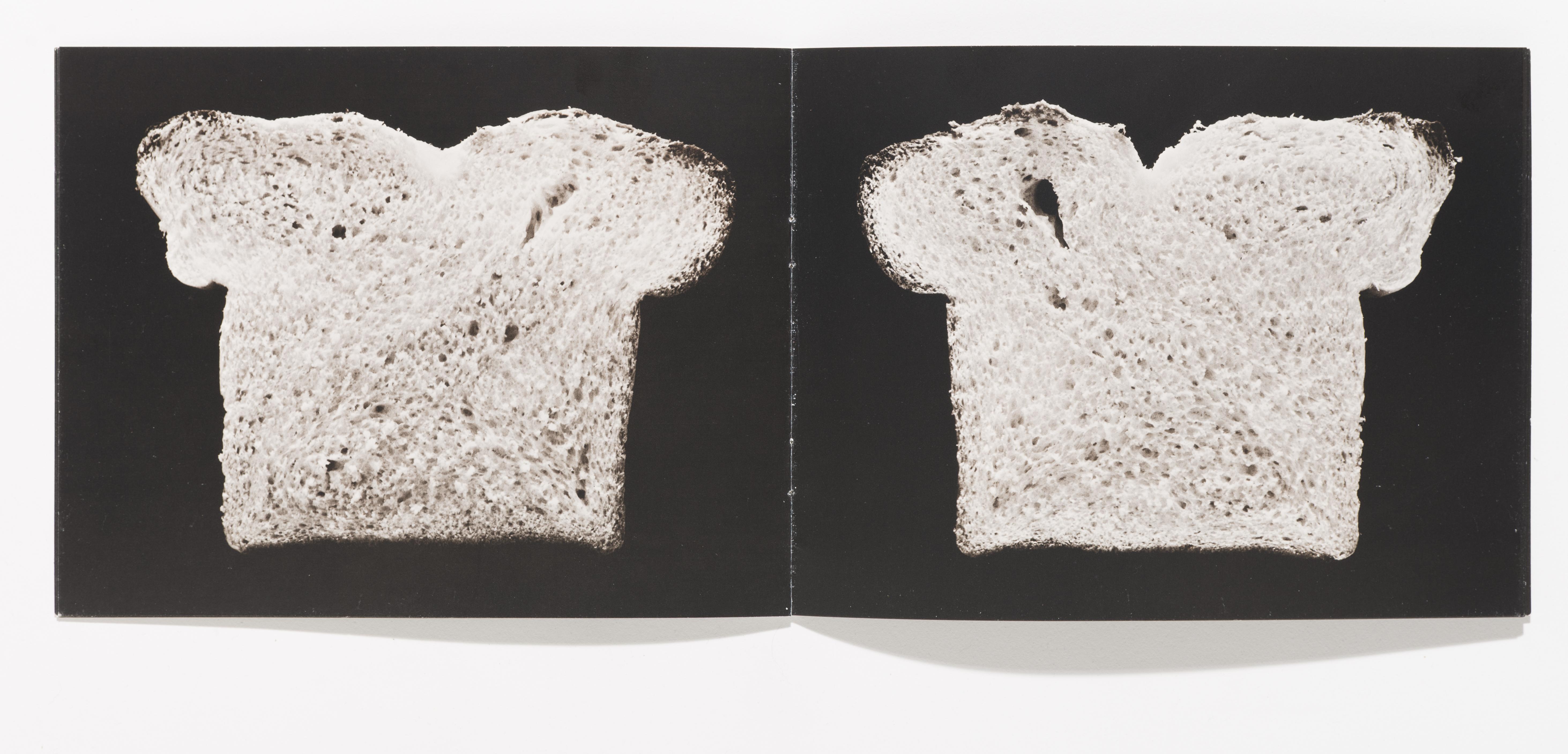

Josephson's chronicling of Chicago's urban environment forms an essential component of his oeuvre and was continued in subsequent decades. He again photographed the glaring light and dark shadows beneath the El tracks in the virtually rococo Chicago, 1964, and returned to this seminal subject matter in Chicago, 2012. By the mid-1960s, however, he had begun to have deeper insight into what he was achieving as a photographer. His subject matter expanded as he realized an essential truth about his undertaking, “The photograph describes very little, actually. Photography can only describe surfaces,” Josephson told an interviewer in 1979, and then added the important caveat, "but it depends how you describe those surfaces."[[14]](#ref-14) As his career unfolded, those surfaces included the urbanscape captured in unexpected juxtapositions, nature as touched by man, as well as his children and his wives and lovers, clothed or nude. With this highly conceptual approach, Josephson was able to realize in his work his maturing ideas about photography and the nature of photographic representation. Seeing the world as surfaces that photography was able to depict changed how he began to describe these surfaces. Josephson began to photograph his own arm extended into the picture plane, holding a postcard, a contour gauge, or a photograph. He began making photographs of photographs by placing his own images back into a setting that had been subsequently documented. Josephson employed not only traditional black-and-white photography but also the techniques of collage and assemblage. He created a genre-defining artists' book, The Bread Book (1973), which documents the slices of a loaf of white bread in a deadpan progression of photos, and experimented with "instant photographs” using the Polaroid SX-70 camera. Over the years, Josephson has continued to pursue all of these subjects and methods of working.

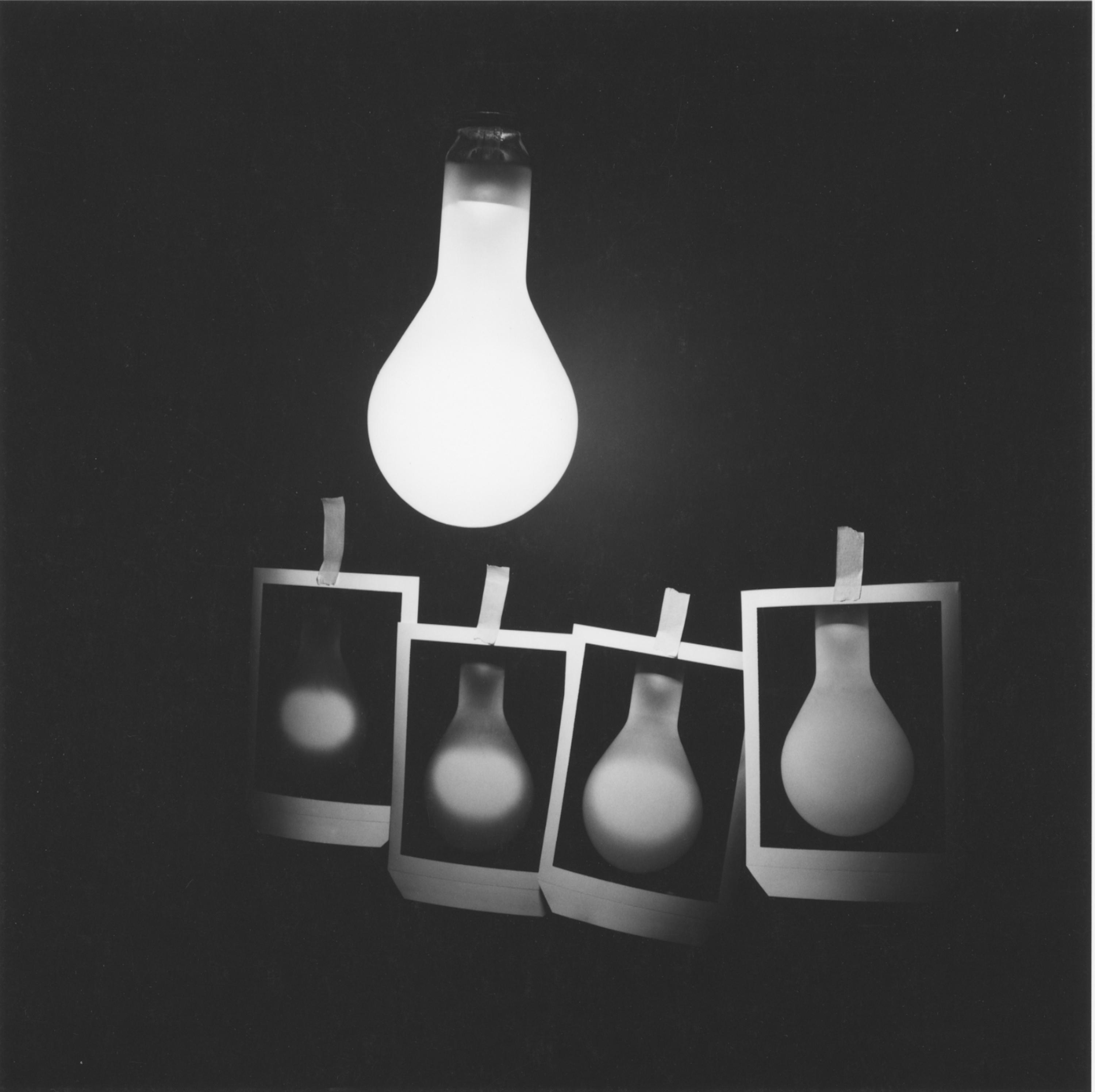

While it is not unusual for photographers to work in series, it is much less common for an artist to work in decades-long, ongoing series punctuated by other, more singular, explorations. In 1961 and 1962, perhaps as a break from the multiple-image landscapes and urbanscapes of his graduate portfolio work, Josephson photographed in-studio still lifes of paper bags. Possibly because this work was so different, it was not widely known until it was published in the catalogue for his 1999 retrospective at the Art Institute of Chicago. Years later, after making numerous photographs for his seminal Images within Images, History of Photography, and Marks and Evidences series, Josephson photographed lightbulbs, exploring the presentation of a sequential image within a singular picture (Polapans, 1973), a theme originally handled very differently in the breakthrough images-within-images Chicago, 1964. Then, in the late 1980s, he produced elegant studies of books, includingChicago, 1988, that clearly refer to the paper bag images insofar as the pages have been folded into geometric shapes and photographed against a black background.

What is consistent over the span of his sixty-year career is that almost all of Josephson's images are made out of doors or inside his home, which he often transformed into a "studio" through the use of backdrops and/or props, but that never became, in any sense, a traditional photography studio. The only time Josephson photographed interiors outside his own home was in 1956 for his undergraduate RIT portfolio, "Front Street, Rochester," which documents dimly lit, rundown shops and bars as in Front Street, Rochester, N.Y., 1956–57. And although he is strongly associated with Chicago, many of Josephson's best-known works were photographed in other places in the United States; in various countries of Europe, including Sweden, England, and France; and in India, where he traveled in 1975 and 1983.

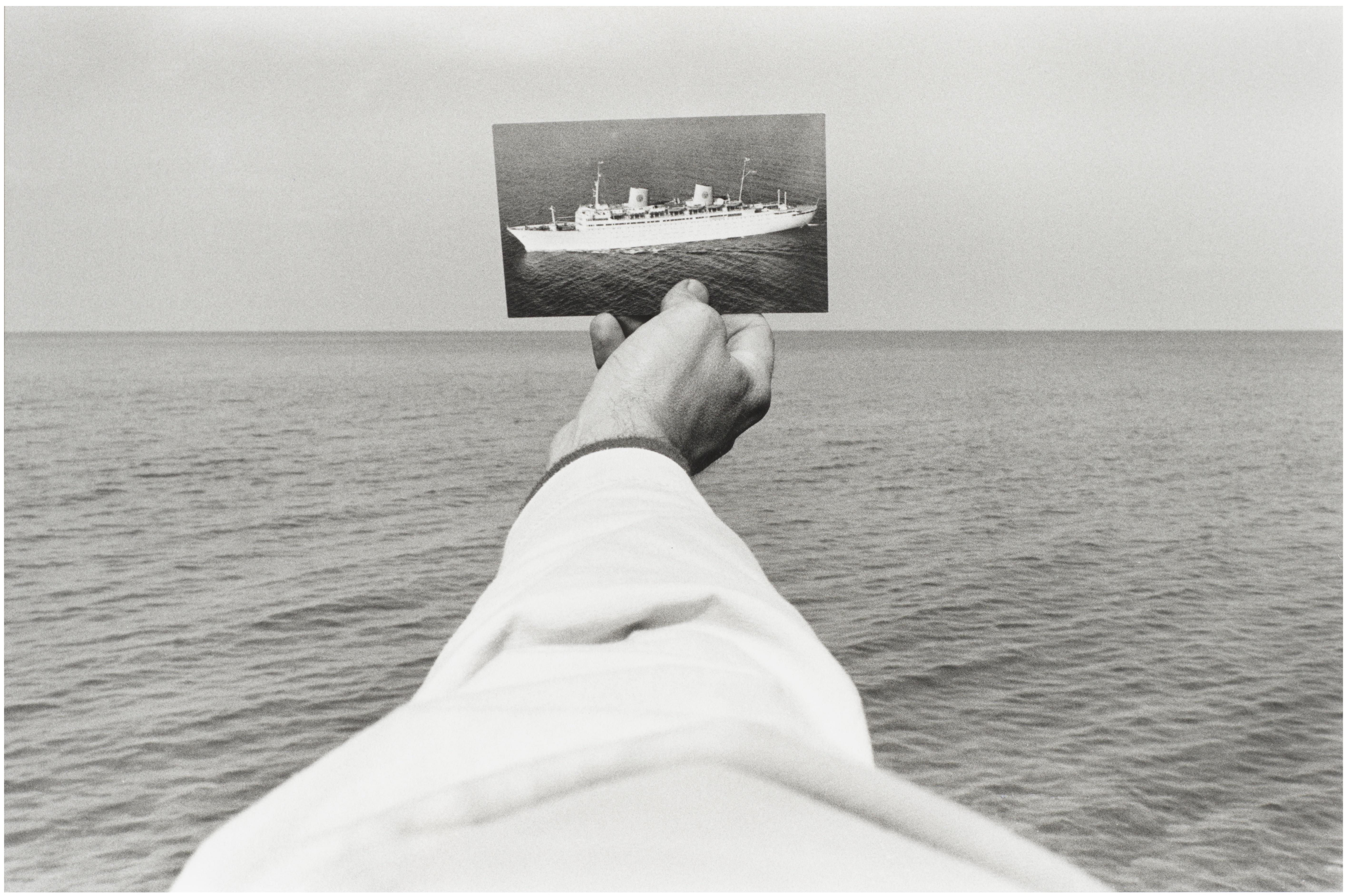

By the 1980s Josephson's reputation as an important and innovative photographer was secure, but his work had been little seen outside photography venues.[[15]](#ref-15) Also by the 1980s, conceptual art was emerging as a mainstay in contemporary art. The happy combination of my having gotten to know Josephson and his work, as I had been his student in the early 1970s, and my position as a curator at the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago prompted a mid-career retrospective there in 1983. Coming to Josephson's work from the dual perspectives of the history of photography and recent developments in contemporary art, I considered it imperative that New York State, 1970, the now-iconic image of Josephson holding a postcard of an oceangoing ship out over Lake Ontario, be on the catalogue's cover. This photograph spoke eloquently of Josephson's vision and illustrated the essence of conceptual art—that the idea structures the artwork and is the starting point for understanding the work. New York State, 1970 was first among equals, so to speak, in demonstrating Josephson as one of the first makers of conceptual photographs.

The MCA, as a museum of contemporary art, was not overly interested in traditional photography, and it is gratifying to look back and recognize that my colleagues also saw something very different in Josephson's work; otherwise, the exhibition would never have occurred. This “something different" was exactly what had caused Josephson, in his Rochester years, more than a bit of trepidation. As accepted as it is now, the idea of making a photograph was once revolutionary. Josephson's own words illustrate this point: "Contriving the image was seemingly a mortal sin; I felt uneasy doing it at first.”[[16]](#ref-16) It was Siskind and Callahan who encouraged him to look at the photograph for what it was—a two-dimensional image that was also capable of curling at the edges to become a three-dimensional object. At ID, founder László Moholy-Nagy taught that the image captured by a photograph was inherently objective given that it accurately recorded lights and darks. Supported by his own innovations and experimentations with photograms and his famous Light-Space Modulator in the 1920s, Moholy-Nagy looked at photography in the most basic way: “It must be stressed that the essential tool of photographic procedure is not the camera but the light-sensitive layer."[[17]](#ref-17) This, of course, reminds all who think deeply about the field that the word "photograph” means “light-writing.” But the popular view of photography was that the content of a photograph in one way or another documented the “real world," a very different idea than that of Moholy-Nagy's, and this belief was deeply ingrained. As recently as 1989, Merry Foresta, in a catalogue for an influential traveling exhibition, The Photography of Invention, penned an essay that was basically a long plea for our understanding that photographs can be “made."[[18]](#ref-18)

As Josephson began his career in the 1960s, he faced interesting times. As evidenced by numerous exhibitions at such venues as the Museum of Modern Art, New York; the Art Institute of Chicago; and the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, fine arts photography was enjoying considerable popularity. Articles on the medium were routinely featured in the New York Times and other big-city newspapers. Perhaps in part because of this new popularity, it remained intimidating for photographers to throw off the traditional beliefs that shaped the medium. At the same time, the newly emerging discipline dubbed “contemporary art" encouraged radical experimentation and the use of photography to document some of this experimentation.

It is difficult to overstate how small, how segmented, and how insular the contemporary art world was as Josephson was beginning his career. Due to timeworn prejudices, photography was cordoned off from the “fine arts”—painting and sculpture.[[19]](#ref-19) Even when photography, as practiced by those with traditional training, received attention from the more broad-minded within contemporary art circles, it remained in the shadow of the rapidly developing "new media" of video, performance, installation, and earthworks. During the 1960s, Marcel Duchamp's anti-retinal stance had fired the intellects of numerous young artists—including Sol LeWitt, Joseph Kosuth, Robert Smithson, Ed Ruscha, and Dan Graham—who established themselves, in what was considered a great advance from Modernism, as conceptual artists. They created works in which, to use LeWitt's famous phrase, “the idea is the machine that makes the art.” Some of these conceptual artworks were in part or solely realized as photographs by individuals with no formal training in photography, including Ruscha's Every Building on the Sunset Strip (1966) or Graham's Homes for America (1966–1967), which was first shown as a slide presentation and later as an illustrated essay published inArts Magazine. Yet for those with traditional photographic backgrounds, even when they engaged with the new visual culture, their efforts remained cloistered within departments of photography, promoted by a relative handful of tastemakers, including curators John Szarkowski at the Museum of Modern Art in New York and David Travis at the Art Institute of Chicago.[[20]](#ref-20)

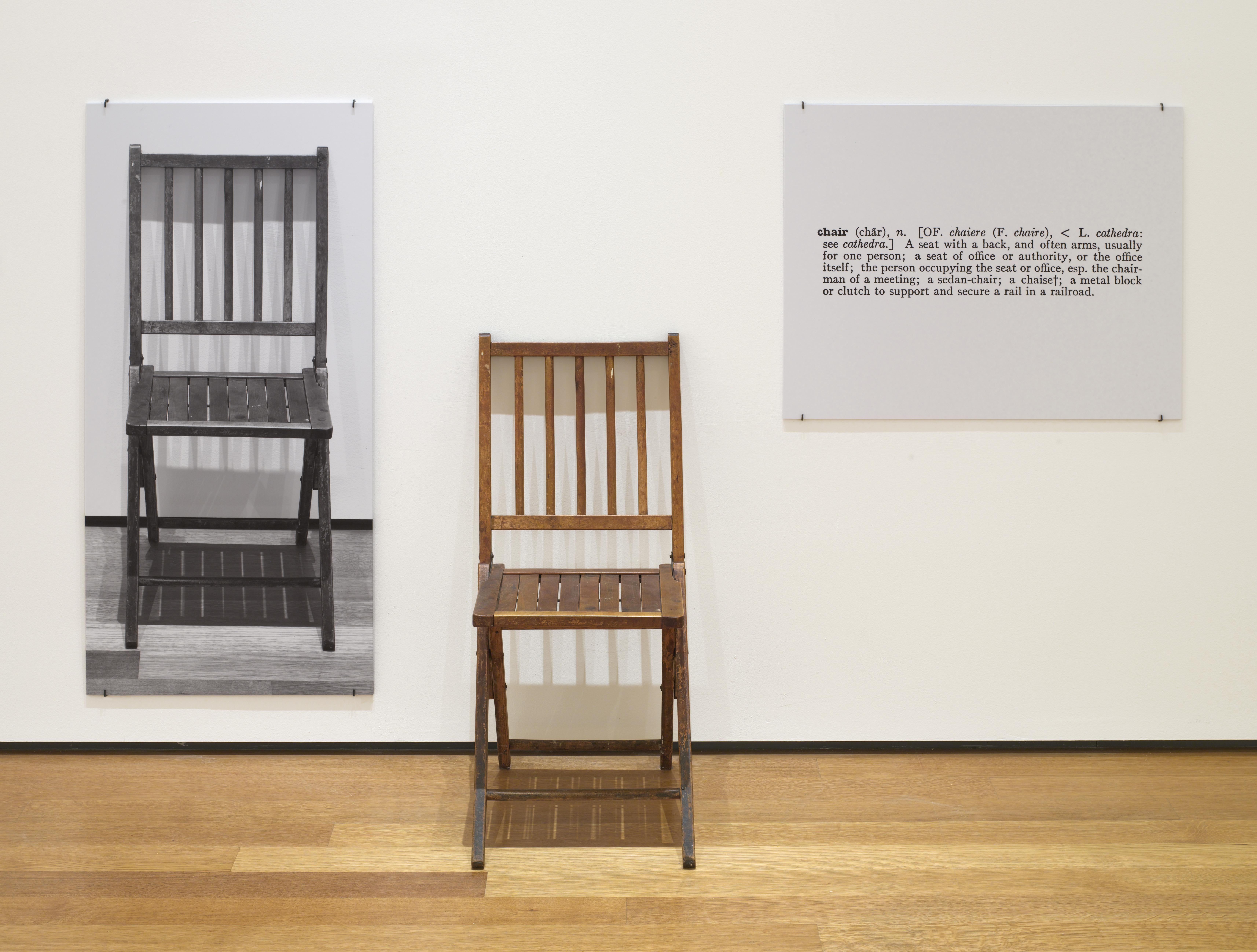

It is instructive to compare the timeline of Josephson's development with that of conceptual art. As Josephson was completing his graduate portfolio at ID, the early projects of the 1960s Fluxus artists—a group that included media innovators Nam June Paik and Yoko Ono, whose performances and happenings were documented by photographs—were in the avant-garde of contemporary art, introducing new ideas into an artworld long dominated by painting. By the time Josephson was completing and exhibiting some of his most compelling and now classic works—Chicago, 1964;Drottningholm, Sweden, 1967; and the postcard collages of the late 1960s and early 1970s—the early conceptual works and influential writings of Sol LeWitt and others were gaining the attention of the most forward-looking individuals in the art world. Artists who did "investigations” similar to those already undertaken by Josephson, notably Joseph Kosuth with his seminal One and Three Chairs, 1965,[[21]](#ref-21) or Robert Smithson, whose “Non-Site” works place maps or aerial photographs near objects taken from the site documented by the images, were also receiving widespread attention.[[22]](#ref-22) The various strands of conceptualism, however, would not gather together until a new generation of artists who used the camera came on the scene in the late 1980s.[[23]](#ref-23) “Conceptual photography," a term freely used today and one that so well describes Josephson's work, elicited only puzzled stares outside a small coterie of artworld insiders until, in the 1990s, it was validated by the success of artist-photographers such as Andreas Gursky and Thomas Struth.

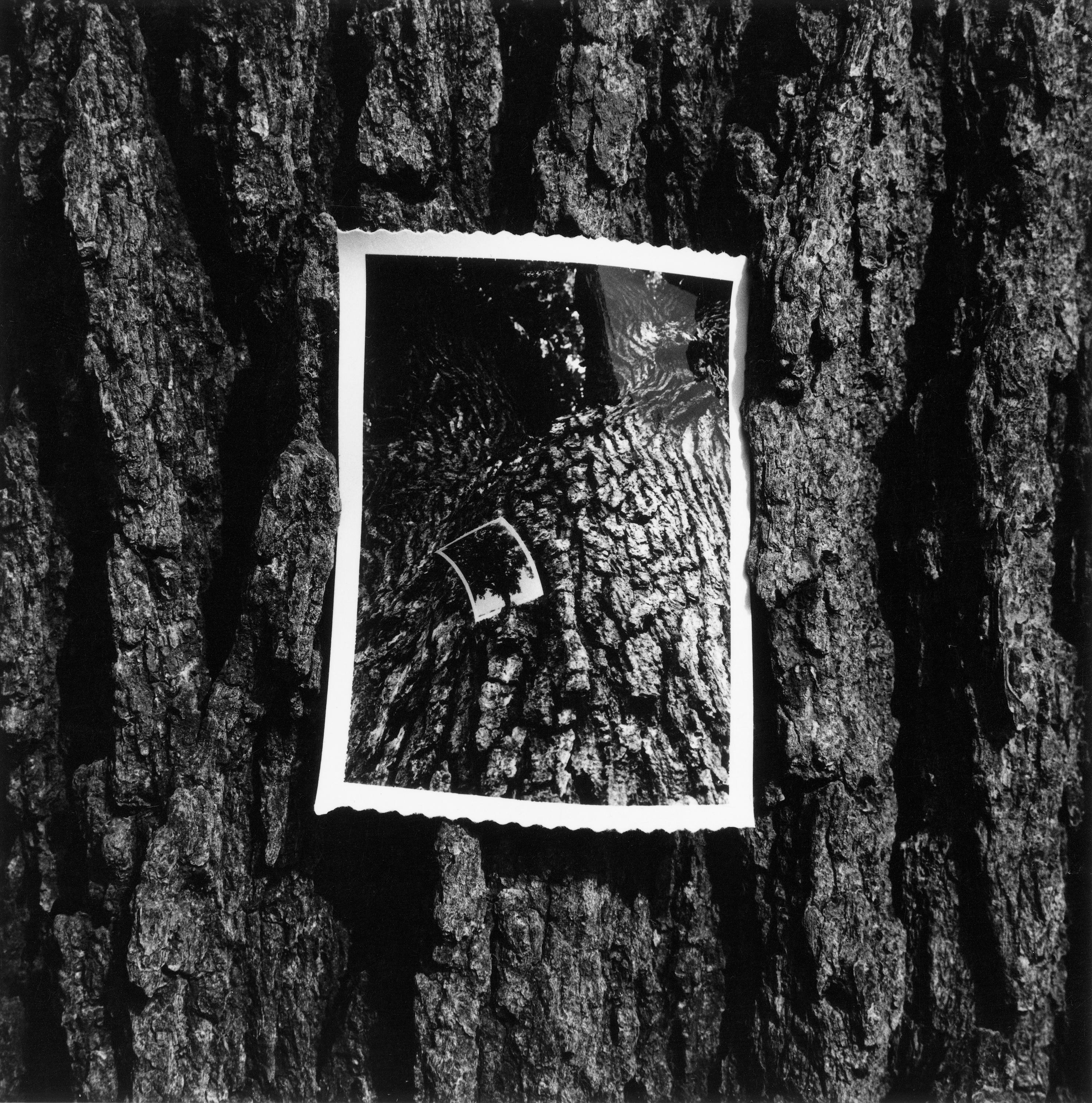

Josephson had very different influences from those of the emerging conceptual artists in Europe and New York. He had been moved by the example of painter René Magritte, among others, and by his own experimental film 33rd and LaSalle from 1960–1962, which shows a building that sported billboards advertising the films Solomon and Sheba and West Side Story in the process of being demolished.[[24]](#ref-24) It was these things that pushed him to explore ideas about photographic representation in the form of “images within images." Chicago, 1964 forcefully announced this breakthrough: a tiny curled photo of the crown of a tree is stuck in the bark of the tree's trunk in a deckle-edged photo of that trunk, which itself is shown wedged between the rough edges of the bark in the final close-up: an image within an image within an image. Josephson explains, "One of the main reasons I conceived this photograph is that I wanted to deal with the idea of a contained sequence of images rather than the usual serial progression. In other words, I wanted to find a way of containing seriality within one image, and move through space and a period of time in one image."[[25]](#ref-25) Although the “image within an image” concept was fully realized in Chicago, 1964, Josephson had explored this subject matter before being entirely conscious of doing so. In a student work that depicts his then-roommate Joe sketching at an easel, the photograph shows not only Joe and the self-portrait he is rendering but his image in the mirror that he is employing to render the self-portrait (Joe, 1959).

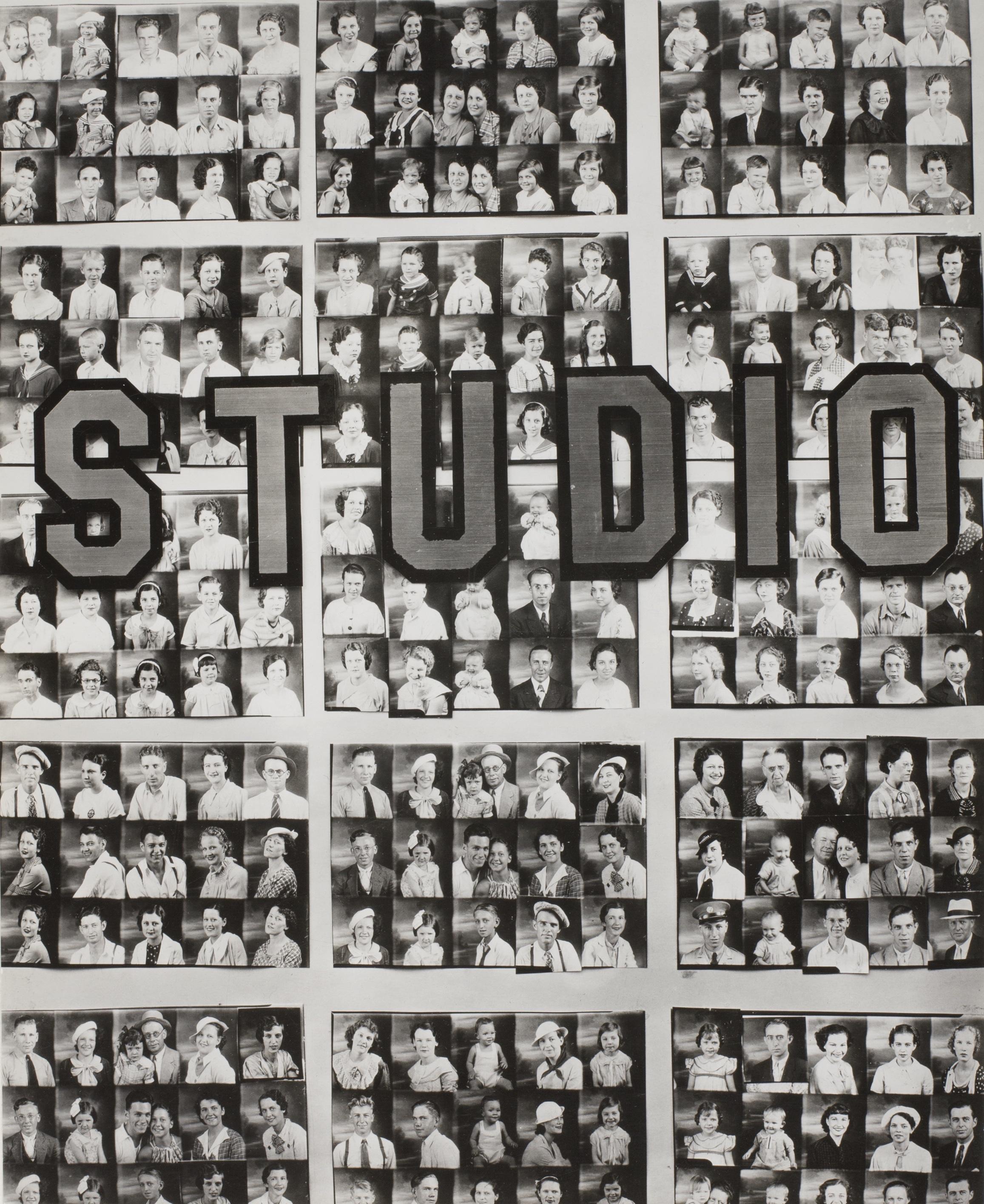

Within the history of photography, there had long been “images within images," most notably Walker Evans's Penny Picture Display, Birmingham, 1936, which shows a photography studio window displaying dozens of examples of its wares, or Margaret Bourke-White's 1937 Louisville Flood Victims, which showed African Americans queuing for relief supplies against the backdrop of a huge billboard that showed an exuberant white family in their new car and proclaimed “World's Highest Standard of Living.”[[26]](#ref-26) Yet these images were made to capture existing situations remarkable for their visual qualities and complexities, and often were intended to be social documents. Prior to Josephson, there was no such thing as the conceptual exploration of what it meant to present an image within an image, or, as Josephson explained in a 1984 interview, “to photograph not entirely just for the image but as an object existing in this other space."[[27]](#ref-27)

Another conceptual breakthrough for Josephson was that he began depicting his own body through cast shadows or reflections in glass or water or by placing an outstretched arm into the composition. Although earlier photography did present images within images, albeit with a different purpose, the appearance of the photographer's arm or shadow as an integral part of the composition had not been generally seen, as such things would be considered mistakes made by amateurs. As early as 1961, Josephson had placed himself in a photo by capturing a silhouette of his arm against a warping grid of darks and lights, in Chicago, 1961. The trope of appearing in one's own photo by means of a reflection in glass or a cast shadow was further explored in such images as Stockholm, 1966, which shows the photographer's full shadow through a window, cast against the contents of a magazine shop, and Matthew, 1963, in which Josephson's shadow falls over his infant son.[[28]](#ref-28)

Josephson's Drottningholm, Sweden, 1967, however, was the first instance of what came to be a trademark: the inclusion of his arm thrust into a photograph, holding an image or object. Drottningholm also reveals Josephson's long-standing interest in “vernacular photography," a category that includes movie posters, snapshots (thus, the deckle edge in Chicago, 1964), and postcards. Locating the exact view snapped years before by a postcard photographer resulted not only in a double-portrait of the private residence of the Swedish royal family inDrottningholmbut also in a number of other classic works that are what Josephson calls “collaborations with anonymous colleagues.” These collaborations include works in which he cut up color postcards to embellish his black-and-white photographs realized from the same angle of view as the postcards, as in the collaged Greyhound bus station inChicago, 1969. This tour-de-force work of art, documentation, and sociology recently found a fitting use as the signature image for the Art Institute of Chicago's 2014 exhibitionThe City Lost and Found. Clever and seemingly effortless, Josephson's postcard collages actually required precise planning and exacting execution, resulting in complex works that utilize the photograph as a tool to create statements about art as they explore and comment on the nature of perception.

Once it became clear to Josephson that the ideas were the most important aspect of his photography, the ideas came quickly. Individual explorations became ongoing series. In Marks and Evidences, which began with the serial examination of a tree (Chicago, 1964), he presented situations that raised the immediate question "What exactly is going on here?" One of the best known and most visually compelling photographs from this series is Stockholm, 1967, which shows a Volvo sedan with a white "shadow." Those who live in southern climes may never decipher the image.

With the History of Photography series, the earliest examples of which were completed in the 1970s, Josephson began to overtly comment on the history and nature of his chosen medium, a complex visual and intellectual endeavor that is in fact a mainstay of conceptualism.[[29]](#ref-29) This series also displays considerable humor, an attitude that, interestingly, art historian Lucy Lippard associates with conceptual art.[[30]](#ref-30) No one prior to Josephson, as photography historian Andy Grundberg has pointed out, had dared to skewer the towering figures of twentieth-century photography.[[31]](#ref-31) In works such as Thinking of E. W. [Edward Weston), Chicago, 1976, which shows an erotically rounded eggplant in front of the groin of a nude man (Josephson himself), or Chicago (History of Photography Series), 1977, which alludes to Edward Steichen's iconic portrait of veiled movie siren Gloria Swanson by portraying naked buttocks behind black lace, Josephson demonstrates, with ribald humor, his knowledge of the history of photography. Yet as Grundberg (and Lippard) point out, this humor was serious business. It is clear that Josephson, while honoring the accomplishment of these photographers, has a more contemporary and conceptual mindset: “The approach I like doesn't ridicule; it makes you think about underlying concepts and pulls you in with humor."1

One of the most subtle allusions in this series is in Chicago (History of Photography Series #2), 1973, which shows a globe-shaped refinery storage unit that almost preternaturally duplicates the ten zones of Ansel Adams and Fred Archer's famous system for the optimal shooting and printing of photographs. Josephson had struggled mightily to learn and properly practice the zone system at the Rochester Institute of Technology. Out of this struggle came an important insight: that a photographer had to have control over every aspect of his craft in order to be successful in producing images using all the required procedures dictated by the zone system. This control simply was not attainable in a school environment of shared darkroom chemicals and equipment. Josephson decided not to completely follow the "system," but to put to use the core principle of understanding the relationships between film exposures and development and the resulting values obtainable on printing papers. No doubt this was a liberating realization given the tyranny of the zone system in midcentury American photography, and one can only imagine how gratifying it was, years later, for Josephson to discover, Duchamp-like, a "ready-made" zone system out there in the real world.

One of the more recent images in the History of Photography series is even more difficult to decipher than the zone system reference in Chicago (History of Photography Series #2), 1973, unless one knows that it was made at the site of one of the world's most famous photographs, Ansel Adams's 1941 Moonrise, Hernandez, New Mexico. Following his own dictum of trying to avoid influencing the viewer with information in a title unless such information is essential, Josephson helpfully called this workCemetery, Hernandez, N.M., Site of “Moonrise" Picture, 1993.[[33]](#ref-33) Finding himself in Albuquerque, Josephson realized he was not far from the Hernandez site. He originally intended to document a sunrise instead of a moonrise, but through a series of misadventures, which included driving past the site because the road sign identifying the town had been removed by locals to misdirect photography tourists, he arrived too late to photograph the sunrise. The resulting image of a ramshackle building with the iconic, now sad-looking, cemetery close at hand is masterful in demonstrating how photography is a medium that can be highly manipulated by the choice of perspective and by how much detail is offered. The romance and mystery of the grand landscape of Adams is replaced by a more contemporary skepticism.

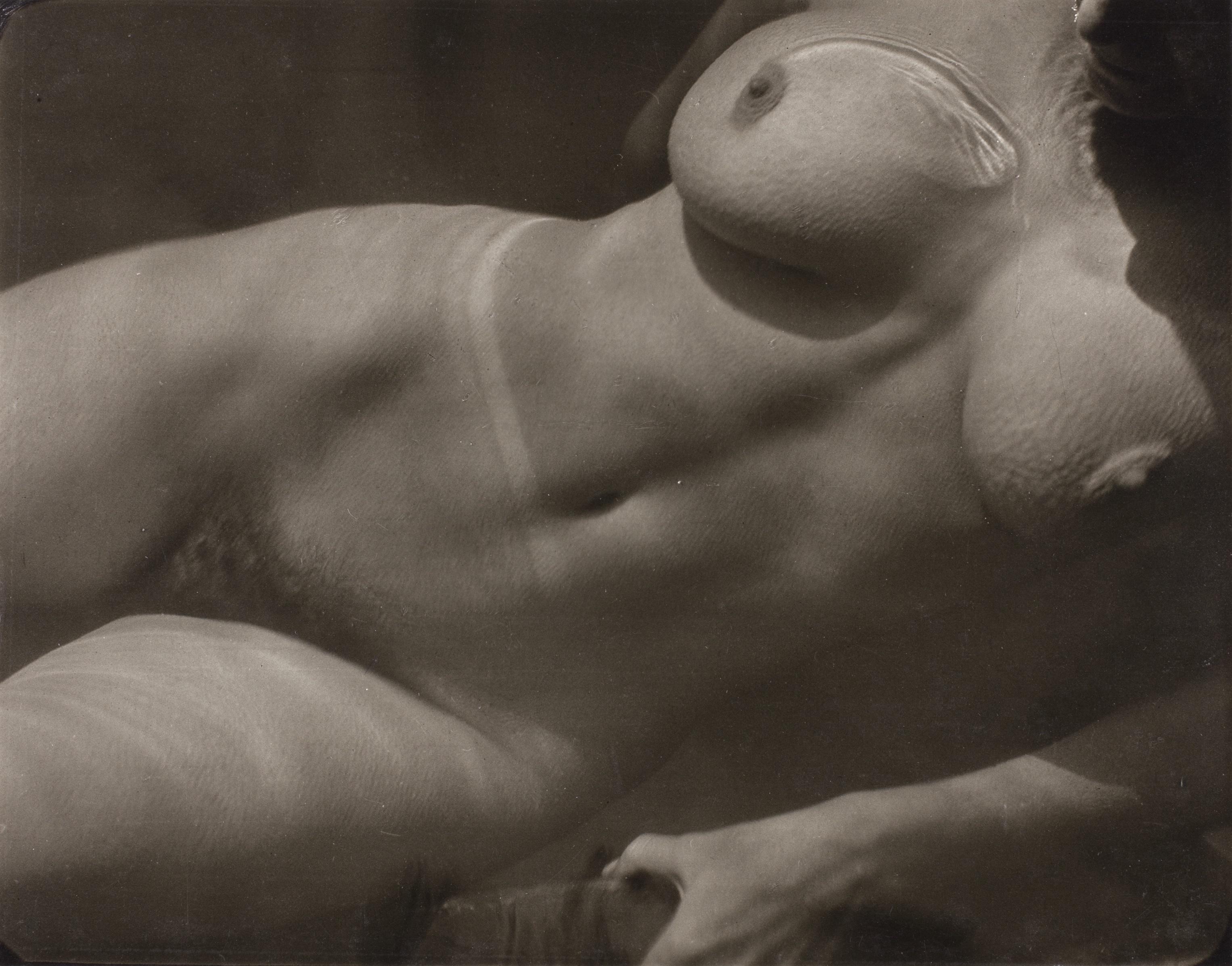

Josephson threw off many of the strictures of twentieth-century photography, but in one regard he remains a traditionalist: the time-honored subject of the nude makes a frequent appearance in all his series. Historically, for feminists and others, the nude as a subject has been a highly contentious issue, with concerns centering on the exploitation of women and the tyranny of the male gaze. Yet Josephson's nudes consistently signal collaboration with the model (most are photographs of his wives or girlfriends), and the resulting images are not presented merely for their erotic or sensual qualities. As always, the idea behind the image predominates. Josephson's use of women as models who are familiar to him resembles that of the great practitioners of nude photography, such as Alfred Stieglitz, who did his best work with wife Georgia O'Keeffe, or Edward Weston, whose two wives and mistresses—including Margrethe Mather, Tina Modotti, and Charis Wilson—were memorialized in extraordinary images. For Josephson, however, the eroticism of the female nude was largely conceptual. One of the early History of Photography works, Michigan (History of Photography Series), 1970, shows a Weston-like nude lying on a bed (also presented as an independent work,Chicago, 1961). This photograph is inserted, upside down in an expanse of sand and rephotographed in these new surroundings. It is a clear reference to Weston's famous 1936 series of Charis Wilson lying in the sand in Oceano, California; the sensuous nude depicted in Josephson's work makes the point that the sensuous nude in the Weston is also merely a photographic image. Michigan (History of Photography Series), 1970 calls to mind Josephson's highly disciplined working habits. As he prepares to photograph, Josephson habitually carries images of made photographs with him that he thinks he might wish to employ in creating a new piece. He had obviously been thinking about the image inChicago, 1961 for a good length of time given the nine-year gap between the two related photographs.

Like Weston and Stieglitz, Josephson had wives and lovers as muses. His first wife, Carol, tragically died from a brain tumor only a few short years into their marriage. A haunting portrait remains (Carol, 1957) that features her face tilted up against a dark background, transformed into a virtual Noh mask. Judy, a later muse, appears in Girl Combing Hair, Chicago (Judy), 1960. In this work, a wire grid captures “screens" of water droplets that reflect multiple tiny versions of the woman posing behind the grid. The transformative quality of water is further explored in Nude in Water, 1963. Sherrill, the mother of Josephson's three children, whom he wed in 1960, is in the bathtub, her rounded belly breaking the water line, forming a brilliant circle of reflected light. This work is all the more poignant because she is pregnant with Matthew, their first child, and thus it marks the beginning of Josephson's extraordinary photographic collaboration with this son. For Josephson, the work also connects to Rebecca Salsbury Strand (1922) by Alfred Stieglitz, a portrait of the wife of Stieglitz's friend, photographer Paul Strand—an image Josephson greatly admires. In this erotic masterpiece, the fulsome torso floats, mostly submerged, the delicate tones of gray barely revealing the water line.

Almost fifty years later, Josephson returned to the theme of a woman in a bathtub in M.Z, 2014; the subject is his companion, Marilyn Zimmerwoman. This photograph especially speaks to Josephson's debt to surrealism, an influence he has freely cited over the years but which has garnered scant critical attention. It is easy to see why, given René Magritte's images-within-images and his deadpan, near-photorealistic painting style, Josephson looked to him as he developed. Josephson's work, however, diverges considerably from classic surrealist photography, which is largely defined by the use of photographic techniques, including photograms and solarization, in the creation of bizarre or dreamlike imagery. InM.Z., 2014, the female presence is contemporary while the costume and play-acting evoke what surrealist instigator André Breton described as a "chance meeting on an ironing board of a sewing machine and an umbrella."[[34]](#ref-34) Although most of Josephson's work is not as overtly surrealist as this piece, the juxtaposition of perfectly ordinary things in unexpected ways is a constant theme. A recent example is a new entry in theImages within Imagesseries,Marilyn, 2009, in which Marilyn Zimmerwoman appears to merge almost magically with the image of Marilyn Monroe on a large poster.

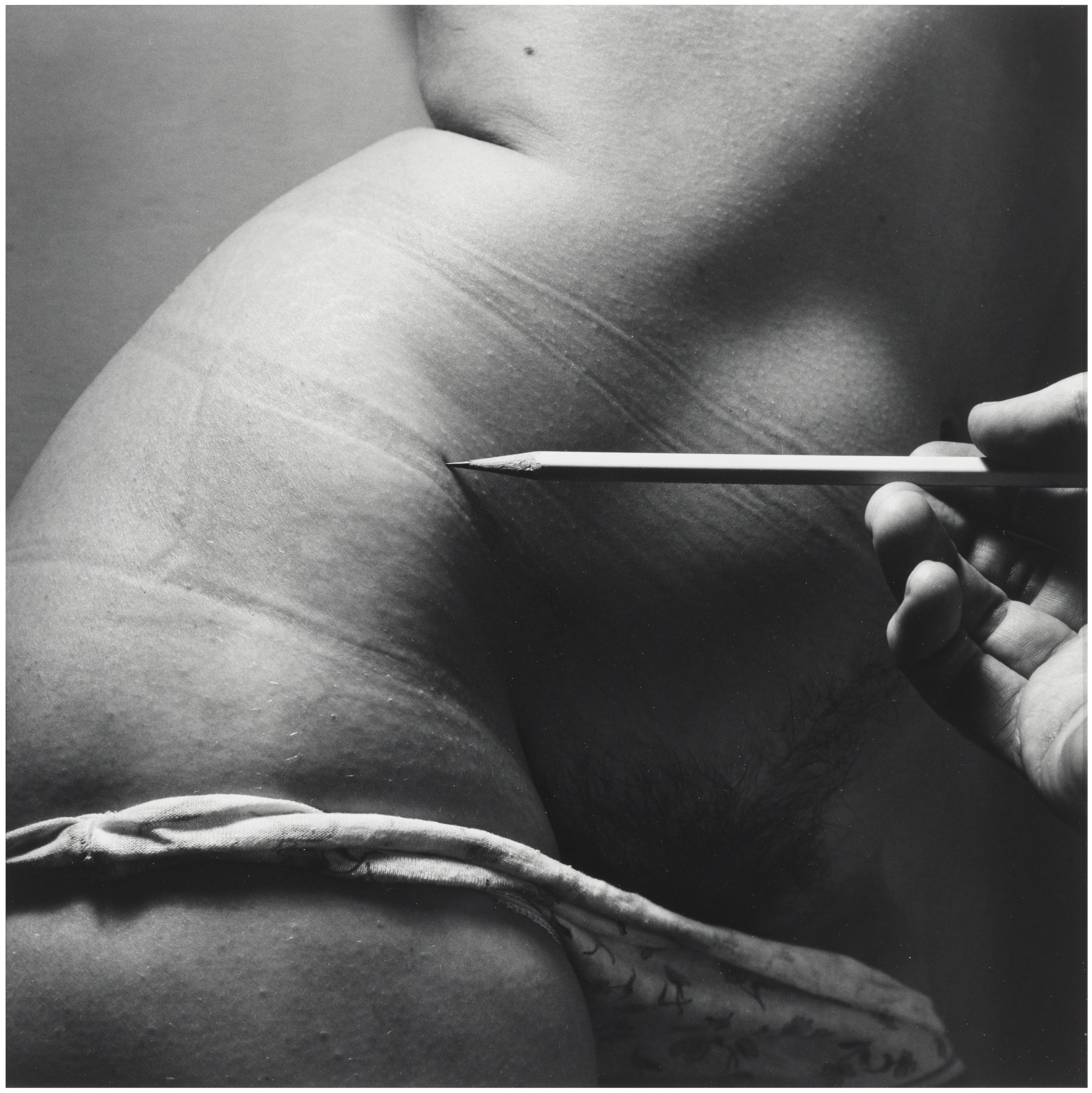

Josephson's third wife, Sally, appears in a number of works, including the naughty Polapan, 1973. In this work, the photographer placed a Polapan Polaroid of Sally's naked crotch over her lying fully clothed on a bed, granting the viewer the adolescent male fantasy of possessing X-ray vision. In Chicago, 1976, from the Marks and Evidences series, Sally's breasts are outlined by a contour gauge (a tool used in wood- and metalworking), and in Chicago, 1976, from the same series, a lightly held pencil, in a sort of archeological investigation, points out the lines of her underwear on her skin. Sally holds an empty photo mat inSally, 1976, creating an image within an image through this simple framing device. One of the most unusual, and surreal, of the images with Sally as a subject, however, isChicago, 1976, which shows a pair of legs, with sandals on the feet, emerging from a gigantic book, a windblown page forming a sensuous curve in the center of the composition. This image was produced long before Laurie Simmons made her career showing works such asWalking Camera (1985), which featured mock-ups of everyday objects with human legs.

While many of the people who appear in Josephson's works are those he knows well—family members, lovers—a significant number feature anonymous people on the street. One of the most striking examples is Chicago, 1964, which captures a man in profile, his head perfectly framed, walking in front of a painted Red Cross logo. The subject's light-colored hat and shirt form sensuous passages of white within the dark cross and background. Other anonymous subjects include the veiled figure in Delhi, India, 1975; the shadows of anonymous passersby reflected in a store window in Chicago, 1972; and a female pedestrian's head, framed by a photo mat held up by Josephson, as she walks past a mural featuring a distorted skyscraper in Chicago, 1980. A unique street shot is the diptych Honolulu, 1968, in which the photograph on the right shows an empty pedestrian crosswalk, the white lines forming a striking “V” shape, while the photograph on the left shows a group of white-uniformed sailors occupying the same crosswalk.

What we gain from [Josephson's] work is no less than the ability to see beyond the apparent reality of photographic description into the realm of photographic representation.

—Andy Grundberg

I was at a New Year's Day gathering in 2015. A gentleman of pre-digital origins was standing, beaming with delight, amidst a cadre of old-timers like himself. “Look what Siri said!” he exclaimed, and I realized he was holding—delicately, respectfully—his iPhone for all to see. Despite listening as hard as she could, I'm sure, Siri had answered the command “Find the restaurant Nookies” with a recipe for the Italian dumpling gnocchi. I thought immediately of Ken. If he'd witnessed this, his laughter would have burst forth like a rumble of thunder on a late summer's afternoon. Gnocchi indeed. This crack in the flow of human endeavor, in “reality," in the way things are and the way they come back to you, is quintessential Josephson territory. How do we capture, process, and make sense of our existence, and perhaps most importantly, how do we remember it? More and more, it seems the answer is by using photography. Kenneth Josephson couldn't have envisioned, as almost none of us could have, an era in which the "selfie" would contribute millions of new images to our collective visual inventory every minute. Nor could he have predicted that people would document their meals on Instagram, or post every snapshot that they take on their Facebook pages, or search the Internet for interesting, inspirational images to "pin" on their Pinterest boards.

Indeed, it used to be hard, a technical challenge, to make a photograph. Josephson admits that one of his main reasons for working in black and white was the difficulty of developing and printing color film. "Studying dye-transfer at RIT made me never want to do color," he said recently.[[35]](#ref-35) It was also expensive making, or for that matter taking, photographs. A serious photographer needed cameras, various lenses, flash equipment, film, darkroom equipment, chemicals, photo paper, a tripod, filters, light meters, and other photo gadgets. Josephson said, in a 1979 interview, that he had purchased a great deal of equipment through the years."[[36]](#ref-36) So when the inexpensive, easy, "instant" color photography of the SX-70 came along in the early 1970s, Josephson was quick to use it in a series that exploited the intimate, snapshotty nature of the three-by-three-inch images. He had little trouble "seeing in color" after years devoted exclusively to black and white. As he explained in a 1984 interview, when he is working in black and white, the colors in the scene he is contemplating don't influence him; he "sees" in terms of value, a habit developed over a period of time. When working in color, however, his ideas center on color.[[37]](#ref-37) A prime example is Anissa’s Dress, 1970, one of Josephson's important, but relatively rare, works of assemblage. Josephson's toddler daughter, wearing a floral printed dress, is shown in a straightforward black-and-white image surrounded by a simple black frame, and both are mounted in the center of the actual dress hanging on a white plastic hanger. The entire assemblage is presented in a shadow box. The deep blacks of the flower-print fabric in the photo are revealed to be bright red "in reality." Indeed, the piece asks, which “reality"?

The SX-70 subjects tend to be casual, explorative. A number of them feature translucent orange drafting triangles that cast equally translucent shadows, as in Chicago, 1979. (These same triangles figure in a number of black-and-white images, such as Chicago, 1979.) Other works feature the nude in a more active and performative mode than in many of the black and whites, as in Untitled, 1979, which shows a piece of fabric streaming up and out from a model's crotch.

Photographs have a way of replacing memory.

—Kenneth Josephson

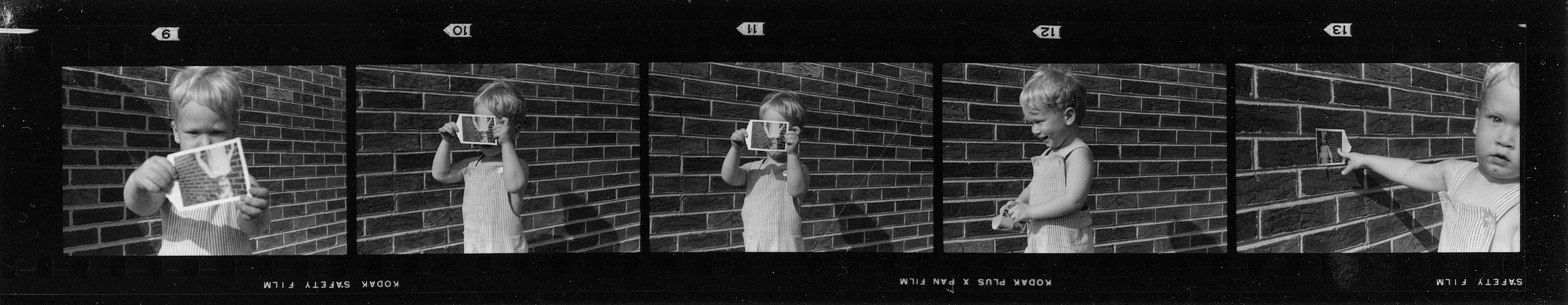

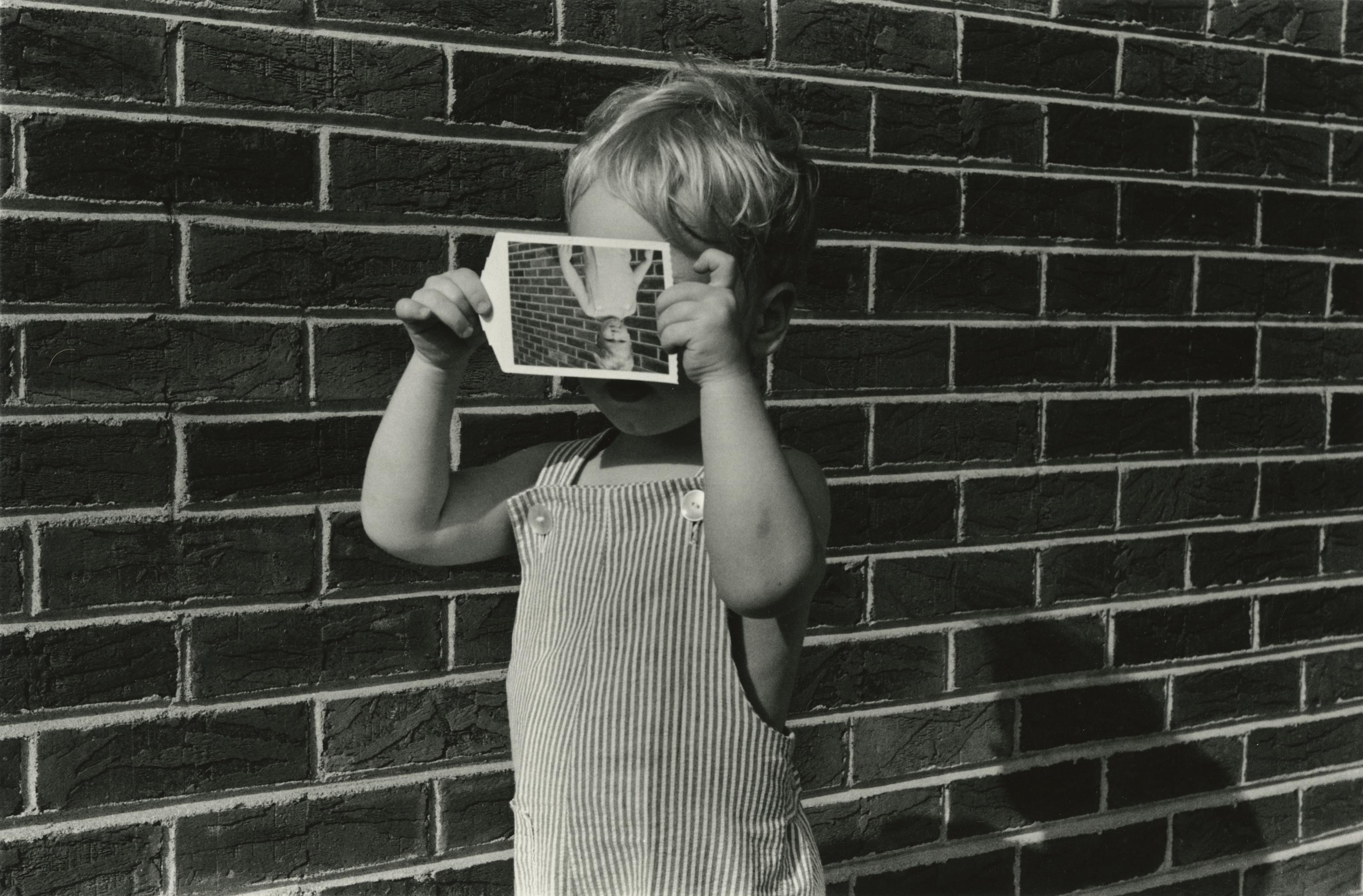

This quote by Kenneth Josephson comes at the end of his personal reminiscences about his firstborn, published in the evocative and poignant 2012 book Matthew. He goes on to say, "I only know Matthew through photographs now."[[38]](#ref-38) Matthew is the newborn infant laid down on the grass, his photographer-father's shadow cast possessively over him, in Matthew, 1963. He is the small boy fitted into a rectangular box in Matthew, 1966 and swinging on a door handle in Matthew, 1965, both widely published images. He is the little blonde boy in pinstriped overalls in the seminal Matthew, 1965. The images in the book demonstrate that Matthew was a collaborative model for some of the photographer's best-known and most personal works. Tragically, Matthew was killed in a car wreck when he was seventeen—thus Josephson's haunting, and hauntingly accurate, observation that “photographs have a way of replacing memory.”

Matthew, 1965 is one of those images that seem like they must have been staged, at least in part. The contact sheet of the negative strip, however, shows the clear progression Josephson nimbly captured, being well prepared for such situations as they arose. In the first frame, Matthew appears to be puzzling over this thing in his hands, a Polaroid of him just made by his father. In the next two frames, he is shown holding the Polaroid up to his eye, using it as a camera, and cocking his little index finger in imitation of snapping a picture. In the next frame he laughs, as if he is in on the joke of taking a picture with a picture. In the last frame he puts the photo right side up against the brick wall that forms the backdrop for all the shots, and points to himself, his face now serious in the way only a young child's can be when figuring out the world. Given the fact that children imitate their parents, it is not surprising that this toddler would have behaved this way around a father who constantly had a he camera obscuring his face, snapping away with his index finger. It was serendipitous that Matthew held the Polaroid backwards and upside down to use it as a “camera," as that made for a superior image, even more so because, in the camera, the picture the lens projects is turned upside down. Josephson also explains that the photograph would have been translucent and that Matthew would have been able to see through it, to some degree.

Frankly, for those familiar with Josephson's oeuvre, his being a family man is not what immediately comes to mind, certainly not in the way one thinks of that great chronicler of childhood, Sally Mann, or of Josephson's mentor, Harry Callahan. But collected together as they were in the book Matthew, the photos of Josephson's firstborn are revealed to be remarkably tender, and they perceptively record what it is to be a child. Matthew rolls on the floor with newspaper comics in Matthew, 1965, and holds up a translucent piece of paper on which he's done a drawing in Matthew, 1967. Josephson's “images within images” are extraordinary explorations of light on surfaces as well as affectionate family photographs. Josephson's daughter Anissa also appears in iconic works, such as Anissa, 1969, which places a snapshot of the baby reaching toward the camera, her face slightly out of focus, atop a photo of her being snapped. It takes a few moments to realize that the snapshot that obscures the photograph is in fact the image that was being captured at the time of Josephson's recording of the scene between mother and child.

This tenderness without sentimentality is a rare thing, a value transmitted to Josephson by Harry Callahan (seen in his extraordinary photographs of his wife and daughter, including Eleanor and Barbara, 1954). Chicago in the 1950s was a bleak place. When not deep in shadows, the city was an unremitting gray. The brick and stone and metal of the buildings and the bridges and the elevated tracks provided a harsh counterpoint to human flesh, and that flesh was typically encased in dark, thick clothing: hats on the men and gloves on the women, overcoats that protected against the seemingly endless cold winds. In this cold, bleak world, Callahan posed a young wife and toddler child against the background of a pipe and slabs of concrete. At that moment, Callahan apparently found the shades of gray provided by the cold concrete backdrop more interesting than the beloved flesh of his family, as the figures are tiny within the composition. Yet the warmth and trust the subjects felt for their chronicler shines out in the face and posture of Eleanor. The casually deposited bag to her left further humanizes what otherwise would be a formal study of lights and darks.

In 1974, paralleling Callahan's work, Josephson photographed his wife Sally, sons Bradley and Matthew, and daughter Anissa, along with the family pet, Zorba, against a geometric concrete background. But it was summer, judging from the sitters' clothing, and the bright sunlight cast deep shadows. The poses are much less formal than those of the stock-straight Eleanor and Barbara in Callahan's photo. Anissa tilts to one side and Zorba perhaps is scratching himself because he's rather blurred. Flat on her back, Sally relaxes, her gaze turned to the sky, and the boys seem to be in the middle of trying to slide down the concrete slabs on which their father has asked them to pose. As in the Callahan photograph, this is a rather anonymous urban space. But, tiny on the horizon, an iconic Chicago water tower can be seen, signaling, “This is my home, my family." Callahan's conflating of the formal and the personal is touchingly and expertly carried forward by Josephson.

Since Kenneth Josephson relocated from Detroit to attend the Institute of Design in 1958, he has not lived anywhere but Chicago, except during yearlong guest-teaching stints, notably in Stockholm in 1966, Honolulu in 1967, Los Angeles in 1981, and Saint-Etienne, France, in 1995. During his student days, and after separating from his wife Sherrill, he lived on Chicago's south side, near ID. When he and Sherrill were raising their family, they had relocated to Riverdale, a far-south suburb near the Indiana border. In recent decades he has moved around a bit, but since the 1980s he has made his home in Chicago's Bucktown-Wicker Park neighborhood. For a while he lived on Wabansia, a street made legendary by Nelson Algren as the place where he carried on his “transatlantic love affair" with Simone de Beauvoir (roughly around the time Josephson was a student at ID). Josephson’s friend, the great image manipulator Robert Heinecken, settled in down the street after retiring from the University of California, Los Angeles, in the 1990s. They shared a love of jokes and humor, of women, and of teaching. Heinecken moved to New Mexico not long before his death from Alzheimer's in 2006. Five years later, at a campsite, Josephson stumbled across an extraordinary object: a whorled fragment of burnt newspaper with the faces of young women still clearly visible, smiling out at varying angles and in varying directions. Titled Thinking of Robert (History of Photography Series), 2014, it documents an uncanny “readymade” that encapsulates important tendencies in Heinecken's art.

Now Josephson lives on the eastern fringe of Wicker Park. During the years he has lived in the neighborhood, Wicker Park-Bucktown has transformed from a marginal working-class enclave of corner bars and streets deserted after sundown into a hipster’s playground, full of brunch spots, vegan restaurants, upscale donut shops, vaping bars, and clothing boutiques. Though so much has changed around him in Chicago, and much has also changed in photography, Josephson remains largely unaffected, living modestly on a still-quiet street and still producing his work himself without the help of assistants.

What is real, Josephson says, is what happens between engaged minds.

—Carl Chiarenza

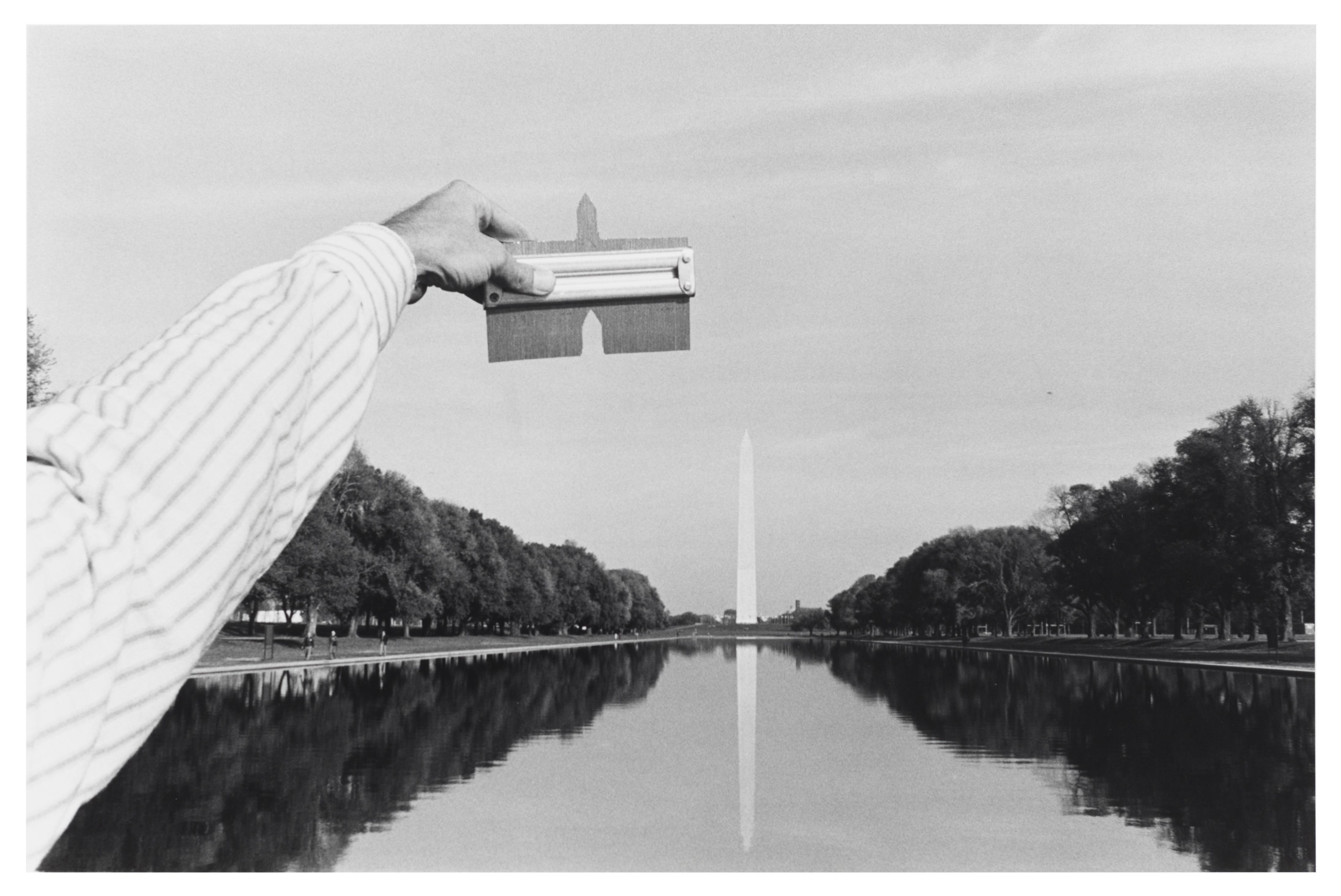

While his reputation as an originator of conceptual photography was being established in the mid-1980s and 1990s,[[39]](#ref-39) Josephson turned his eye to traditional photographic genres, including landscape and travelogue—themes he had explored, albeit in a more rigorous manner, in the 1960s in his Marks and Evidences and Archaeological series. Examples include Wisconsin, 1964, which shows a grassy expanse with a mysterious rectangular form bisecting the image (the result of a piece of wood having been removed from the landscape), and Washington, D.C. (Archaeological Series, Six-Inch Contour Gauge), 1975, showing Josephson's outstretched arm holding a contour gauge set in the distinctive shape of the Washington Monument, which appears in the distance. These more recent works are not as well known, perplexing those who view artists' careers as inevitably linear and forward-moving. Josephson has been unfazed, explaining simply, “I made several trips to Europe. I wanted to change my work in some way, to do something different.” He realized lovely landscapes and poetic images, as inEngland, 1990, in which a Warhol-esque flowered cloth billows off a clothesline, adding confusion to the background scene of hedgerows and gently rolling hills. During a residency in France in 2003, he produced a number of pieces in which, referring to his own earlier mirror works as well as Robert Smithson's, he placed mirrors in various environments with witty results. An example isNear Lectoure, France, 2003, in which meticulously angled mirrors placed along the risers of an ancient stone staircase reflect the identical knotty twist of tree branches.[[40]](#ref-40)

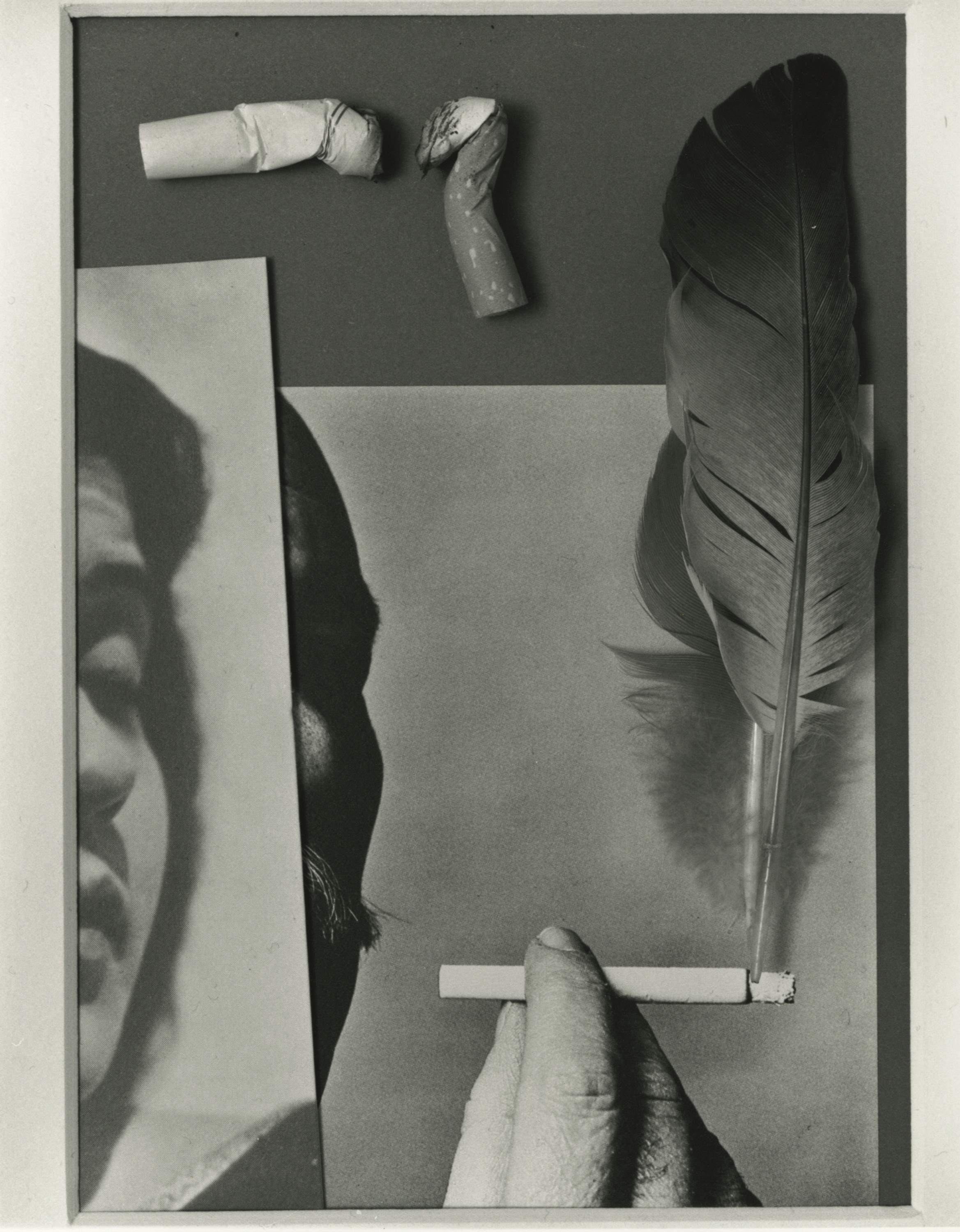

By no means were all the "different" works created during this period landscapes. Harkening back to his assemblages, even though it involved rephotographing of images and photographing of objects, Untitled (History of Photography Series), 1991 features two famous portraits: Irving Penn's study of the painter Barnett Newman, languidly holding a lit cigarette, and Edward Weston's portrait of Tina Modotti, her eyes heavy, her lips pursed. The similarities between the two iconic images are startling, and Josephson plays up the parallels by laying the Weston atop the Penn, aligning their almost identical silhouettes. The structure makes it apparent that it could have just as easily been Modotti's pursed lips reaching for the cigarette held in Newman's hand. Adding a further complication to the montage, atop the smoke plume of the cigarette Josephson laid a plume of an entirely different sort—an actual feather. Cigarette butts, in an homage to Penn's 1970s series featuring the lowly subject matter, litter the top of the image, as these iconic portraits are revealed to be mere pieces of paper, and not in good shape either. The lower corner of Modotti's portrait is dog-eared and, as an object, is clearly subject to the vicissitudes of the world.

[FIG. 11. Xaviera Simmons (American, b, 1974), On Sculpture #2, 2011. Color photograph; 40 x 50 in. (101.6 x 127 cm). Edition of 3. Courtesy David Castillo Gallery, Miami, and Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago.]

Kenneth Josephson retired from teaching in 1997 and has no direct protégées. Yet his influence is discernible in the work of the rising generation of artists who use photography. A clear example is the young American artist Xaviera Simmons, who riffed on Josephson's New York State, 1970 in her work On Sculpture #2, 2011, which substitutes a wrinkled tear-sheet showing numerous people jumping off a boat for Josephson's postcard of a passenger ship.[[41]](#ref-41) Jimmy Robert, a Guadeloupe-born, Brussels-based artist, photographs scraps of paper on his studio floor, rephotographs the images along a baseboard, and places images of himself performing various actions either scrunched into a box or rolled into the pages of a book. Lisa Oppenheim, a New York-based artist, culled snapshots of sunrises posted on the Internet by troops in Iraq and held these images up against the horizon of sunrises in New York for her 2006 slideshow The Sun Is Always Setting Somewhere Else. And Josephson's vision pervades the larger image world of advertising and the Internet. Chevrolet produced a commercial some years ago showing people's arms holding vintage photos of classic Chevy vehicles against current views of the same setting. Young image makers post photos on their websites and Instagram pages "in the style of Kenneth Josephson”: images atop images, hands and arms holding up images (some on tablets) and objects. Numerous others “pin” his images to their Pinterest boards, indicating their admiration.

[FIG. 12. Jimmy Robert (French, b. Guadeloupe, 1975), Untitled, 2010. Archival ink-jet print and medium-density fiberboard with beech veneer frame; print 31 1/2 x 31 1/2 in. (80 x 80 cm), frame: 12 x 24 x 36 in. (30.5 x 61 x 91.5 cm). Courtesy Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago. © Jimmy Robert, courtesy Stigter van Doesburg, Gallery, Amsterdam.]

Josephson has certainly shaped our world with his photographs. His long career in the medium has produced a visually coherent and always interesting body of artworks that strongly reflect a time and place while paradoxically remaining uncannily timeless. Even though the images were made in a different era, one with fewer options and with analogue means, they are startlingly contemporary and full of ideas that interest the digital generation: ideas about the nature of seeing, “reality," human aspirations, and what it means to be a human observing the world.

This essay was originally published in The Light of Coincidence: The Photographs of Kenneth Josephson, (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2016).

NOTES

- One of his few straightforward still lifes, Self-Portrait, 2004, shows Josephson at eighteen in front of a bronzed cowboy boot being “stepped on” by a bronzed stiletto high heel.

- Originally the New Bauhaus, the Institute of Design was set up as an autonomous school by László Moholy-Nagy in 1937; in 1949 it was absorbed into the Illinois Institute of Technology. Educator and photographer John Grimes, long associated with ID, described the photography program as isolated "within a school of design, which was itself a neglected and misunderstood part of a school of engineering”—features that conversely made it strong during the period in which Josephson was studying there.

- Josephson has said Callahan called Detroit in those days “a cultural wasteland," and that he "was from Detroit, too, and knew it well.” Harry Callahan and His Students, A Study in Influence (Atlanta: Georgia State University Art Gallery, 1983).

- Josephson later stated he probably would have preferred to attend ID over RIT, given that the technical and commercial aspects of the field did not interest him, but at that point, he’d never heard of it.

- Besides Minor White, these contacts included photographers Ralph Hattersley and Charles Arnold, and legendary photo historian Beaumont Newhall.

- Josephson had applied for a scholarship to ID, but did not receive it.

- In addition to his influential career as a teacher, Josephson was a founding member, in 1963, of the Society for Photographic Education, which promoted professionalism in the rapidly emerging field.

- Kenneth Josephson, “Thoughts on My Work and Process," in Kenneth Josephson: Selected Photographs (Berlin: only photography, 2013), 59.

- These photographers, except for Ishimoto, received their master’s degrees from the Institute of Design between 1959 and 1962.

- Multiple sources verify that Callahan and Siskind did not routinely present their work to their students, fearing undue influence, but both showed in various exhibitions around the city, and their work would have been known.

- More precisely, it was located in the basement of the famous Mies van der Rohe Crown Hall, 3360 South State Street.

- Besides recommending him for the SAIC job, this impressive portfolio was excerpted in 1961 in the leading photography journal Aperture, a high honor for a journeyman photographer.

- At this time the area surrounding the Illinois Institute of Technology, of which ID was a part, was being transformed by vast urban renewal projects such as the building of public housing (the now-demolished Robert Taylor Homes). Josephson chronicled the urban renewal in his film 33rd and LaSalle, which documents the razing of a building. John Grimes, “Photography on Its Own," in David Travis and Elizabeth Siegel, ed., Taken by Design: Photographs from the Institute of Design, 1937–1971 (Chicago: Art Institute of Chicago, 2002), 155.

- Unpublished interview with Michael Anisfield, 1979.

- Josephson had had an important solo show in 1971, organized by the Visual Studies Workshop, Rochester, which had traveled widely throughout the United States and Canada. And, as happens with many Chicago-based artists who are underappreciated in their hometown, he had shown in Stockholm, Milan, Vienna, Liverpool, Hamburg, and Kassel, largely under the auspices of museum photography departments.

- Josephson, “Thoughts On my Work and Process," 59. Josephson was speaking of his time as a recently graduated RIT student. Yet at the same time, Josephson's ID experience was expansive, for he also has stated, "At I.D. you could use any means that you wanted to get across your ideas.” Sylvia Wolf, Kenneth Josephson (Chicago: Art Institute of Chicago, 1999), 177.

- László Moholy-Nagy, “Photography Is the Manipulation of Light," reprinted in Andreas Haus, Moholy-Nagy: Photographs and Photograms (New York: Pantheon Books, 1980), 47.

- The Photography of Invention, American Pictures of the 1980s, 10, describes the difference between “taken” and “made” this way: “A picture is 'taken' by discovering or selecting an already-existing subject and accurately transcribing it, revealing and exploring a fragment of the real world . . . [in] a record and commemoration of a specific time and place—e.g., a 'decisive moment' (Henri Cartier-Bresson) or a 'supreme instant' (Edward Weston) of reality. This so-called straight or pure photography bears with it the presumption of truth, in part because of photography's scientific origin as light traced on paper, its reaffirmation of Renaissance perspective, and our widely shared cultural proclivity to believe in the verifiable objectivity of photographs. This credibility is ultimately based on the photographer's seeming lack of interference with the subject. . . . In 'made' pictures, the photoartist . . . creates or otherwise affects the subject photographed.” Josephson in fact utilizes both methods, but considers both “making” photographs.

- Andy Grundberg also chronicles the "Tale of Two Photographies” in his excellent essay “Kenneth Josephson: The Photograph and the Möbius Strip," in Wolf, Kenneth Josephson.

- Szarkowski included Josephson in his groundbreaking 1978 exhibition Mirrors and Windows at MoMA. Travis was very supportive of Josephson and all the ID-educated photographers, and the Art Institute holds dozens of his works in its collection.

- Josephson did his own “conceptual investigation" of the chair in France, 1995.

- Smithson's own foray into photographing a scene, printing out the image, and placing it back into the environment he documented—Photo-Markers (from Six Stops on a Section), Laurel Hill, New Jersey, 1968—postdates Josephson's investigations by four years.

- The emergence in the late 1980s of the "Pictures” generation of artists who used photography, including Sherrie Levine and Cindy Sherman, combined with a rising interest in older conceptual artists who had continued to work into the 1980s, firmly established conceptualism. By the early 1990s, supported by an abundance of literature—including Ursula Meyer's Conceptual Art (first published in 1972) and various writings by the critics Benjamin H. D. Buchloh, Rosalind Kraus, Lucy Lippard, Robert Pincus-Witten, and many others—conceptualism was in the mainstream of contemporary art.

- In locating his inspirations for Images within Images, Josephson cites, besides Magritte, Jasper Johns's flag paintings as well as the work of photographer Frederick Sommer, who briefly taught at ID (although before Josephson was enrolled). Interview with the author, October 6, 2014.

- Interview with the author, February 12, 2015.

- As one might expect, the phenomenon of "images within images" can be found in works dating from the earliest years of the medium, often in views of artists' and photographers' studios and art patrons' salons.

- [Interview with Kenneth Josephson](), directed by Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago. Original release by the Education Department at the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago, 1983.

- This aspect of the informed, yet seemingly casual or even accidental, photograph was taken up by Lee Friedlander and others later in the 1960s and promulgated by John Szarkowski as “social landscape," a new, more conceptual, twist on street photography. This new genre was launched in the 1967 Museum of Modern Art exhibition New Documents, which examined “photographers [who] redirected the technique and aesthetic of documentary photography to more personal ends . . . not to reform life but to know it, not to persuade but to understand." The exhibition featured Lee Friedlander, Garry Winogrand, and Diane Arbus. Museum of Modern Art press release, Tuesday, February 28, 1967.

- Josephson revealed in an interview with the author that he didn't always title the History of Photography works, as he wanted to “keep it more open-ended," and this open-endedness is always on his mind: "I wanted to make an interesting photograph. Whether someone 'got it' or not didn't matter as much.” October 6, 2015.

- Lucy Lippard, “The Dematerialization of Art," Art International, Vol. XII, No. 2 (February 1968), 267.

- Wolf, Kenneth Josephson, 14.

- Alan G. Artner, "Josephson: Seeing the world through a lighthearted lens," The Chicago Tribune, Arts and Books section, March 27, 1983.

- Josephson has admitted that he is “not terribly good at combining words and images and the title gives the viewer a direction. I would rather the person not be prejudiced by another thought that [I am] imposing on them.” Interview with Kenneth Josephson.

- Adapted from Comte de Lautréamont.

- Interview with the author, November 27, 2014.

- Kelly Jain, ed., Nude: Theory (New York: Lustrum Press, 1979), 105.

- Interview with Kenneth Josephson.

- Kenneth Josephson, “Matthew: A Collaboration," in Matthew (Chicago: The 2054 Press, Stephen Daiter Gallery, 2012), 5. Courtesy of the artist and Stephen Daiter Gallery, Chicago.

- It is in the 1999 Art Institute of Chicago catalogue that the descriptions of Josephson a conceptual photographer are explicit.

- Smithson is famous for his Mirror Displacements, the earliest of which dates from 1969.

- This was in fact the boat on which Josephson traveled back to the United States following his 1966 stay in Stockholm, and he acquired the postcard while in transit.

Kenneth Josephson on leave from the army, 1953. Collection of the artist

Joseph Kosuth, One and Three Chairs, 1965. Wood folding chair, mounted photograph of a chair, and mounted photographic enlargement of the dictionary definition of "chair"; chair: 32 3/8 x 14 7/8 in. (82 x 37.8 x 53 cm); photographic panel: 36 x 24 1/8 (91.5 x 61.1 cm); text panel: 24 x 24 1/8 in. (61 x 61.3 cm). Larry Aldrich Foundation Fund, The Museum of Modern Art. © 2015 Joseph Kosuth/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Digital Image © The Museum of Modern Art/Licensed by SCALA/Art Resource, NY

Walker Evans, Penny Picture Display, Savannah, 1936 printed c

Margaret Bourke-White, African American flood victims lining up to get food and clothing from a relief station in front of a billboard ironically proclaiming WORLD'S HIGHEST STANDARD OF LIVING/THERE'S NO WAY LIKE THE AMERICAN WAY, 1937

Photo by Margaret Bourke-White/Time & Life Pictures/Getty Image

Ansel Easton Adams, Moonrise, Hernandez, New Mexico, 1941. Gelatin silver print, 14 1/2 x 19 in. (36.9 x 48 cm). Peabody Fund, 1952.203, The Art Institute of Chicago

Photography © 2015 The Ansel Adams Publishing Rights Trust

Alfred Stieglitz, Rebecca Salsbury Strand, 1922. Gelatin silver print; image/paper: 3 5/8 x 4 5/8 in. (9.2 x 11.8 cm), mount: 13 1/8 x 10 1/2 in. (33.6 x 26.6 cm). Alfred Stieglitz Collection, 1949.734, The Art Institute of Chicago. This work is represented by the Artists Rights Society (ARS)

Kenneth Josephson, M.Z., 2014. Gelatin silver print. Courtesy of the artist and Stephen Daiter Gallery, Chicago.

Kenneth Josephson, contact strip of Matthew, 1965. Gelatin silver print. Collection of the artist. Courtesy of the artist and Stephen Daiter Gallery, Chicago

Harry Callahan, Eleanor and Barbara, Chicago c

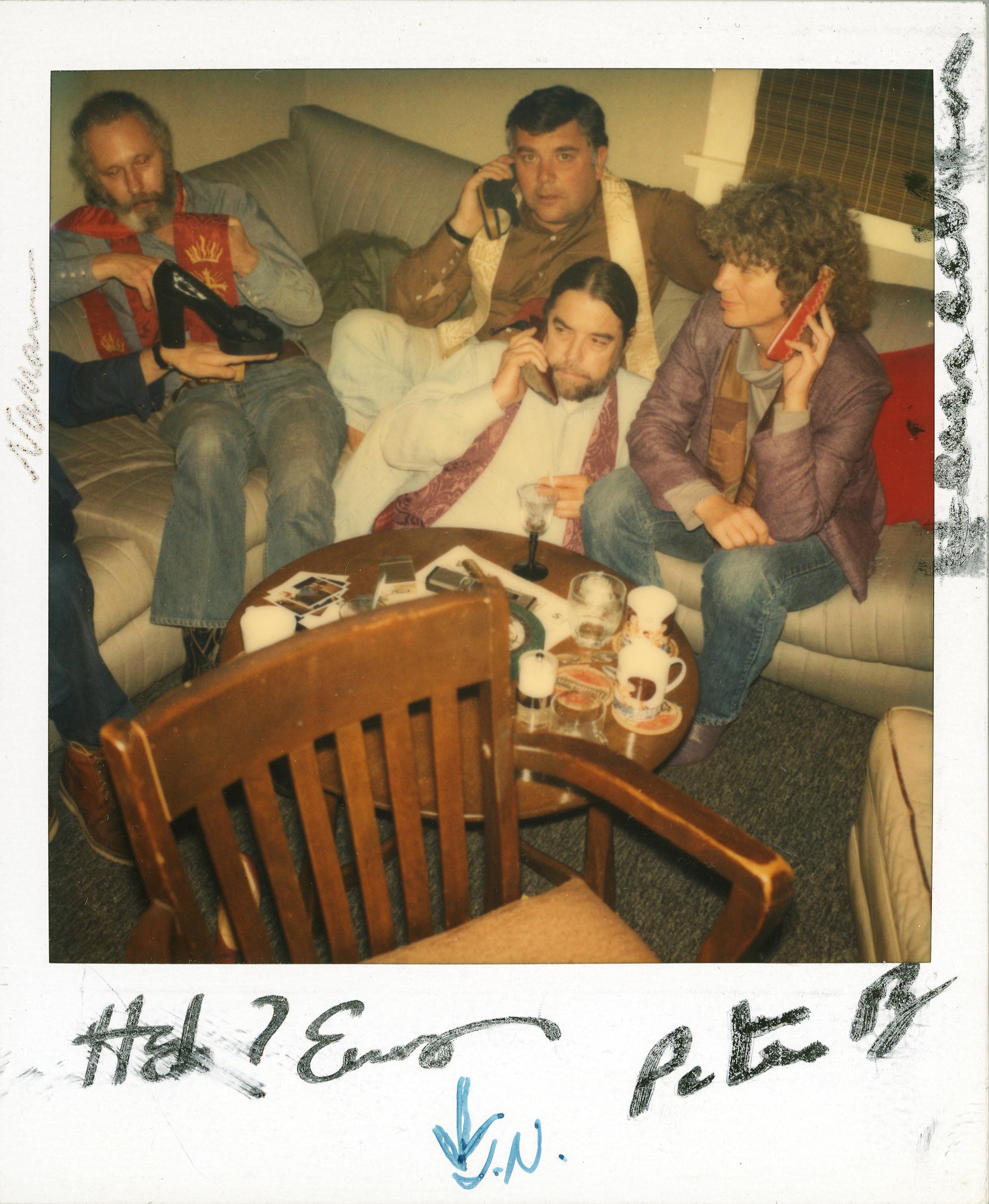

Kenneth Josephson (left) with Robert Heinecken (center, in white shirt), ca. 1980–82. Also in photo are Peter Bunnell (behind Heinecken) and Chris Enos. SX-70 Polaroid; collection of the artist. Courtesy of the artist and Stephen Daiter Gallery, Chicago

Xaviera Simmons, On Sculpture #2, 2011. Color photograph; 40 x 50 in. (101.6 x 127 cm). Edition of 3. Courtesy David Castillo Gallery, Miami, and Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago

Jimmy Robert, Untitled 2010

Kenneth Josephson, The Bread Book, 1973. Offset print on paper; saddle-stitched, softcover. MCA Chicago Artists' Books Collection, gift of the artist, 81.406

Photo © MCA ChicagoPolapans

Kenneth Josephson, Polapans, 1973, 1973. Gelatin silver print; 9 1/16 x 9 1/16 in. (23 x 22.9 cm). Courtesy of the artist and Stephen Daiter Gallery, Chicago

Installation view, Kenneth Josephson Retrospective, MCA Chicago, Mar 25–May 22, 1983

Photo © MCA Chicago

Kenneth Josephson, Chicago, 1964, 1964. Gelatin silver print; 9 x 9 in. (22.9 x 22.9 cm). Courtesy of the artist and Stephen Daiter Gallery, Chicago

Kenneth Josephson, Stockholm, 1967, 1967. Gelatin silver print; sheet: 11 x 14 in. (27.9 x 35.6 cm). Collection Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago, Illinois Arts Council Purchase Grant, 1980.13

Photo: Nathan Keay © MCA Chicago

Kenneth Josephson, Michigan (History of Photography Series), 1970, 1970. Gelatin silver print; 9 x 9 in. (22.9 x 22.9 cm). Courtesy of the artist and Stephen Daiter Gallery, Chicago

Kenneth Josephson, Chicago, 1976, 1976. Gelatin silver print; framed: 19 1/2 x 19 in. (49.5 x 48.3 cm). Collection Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago, gift of Katherine S. Schamberg by exchange, 2014.6

Photo: Nathan Keay © MCA ChicagoMatthew, 1965

Kenneth Josephson, Matthew, 1965, 1965. Gelatin silver print; 7 7/8 x 12 in. (20 x 30.5 cm). Courtesy of the artist and Stephen Daiter Gallery, Chicago

Kenneth Josephson, Thinking of Robert (History of Photography Series), 2014, 2014. Gelatin silver print; 8 3/4 x 12 13/16 in. (22.2 x 32.5 cm). Courtesy of the artist and Stephen Daiter Gallery, Chicago

Kenneth Josephson, Washington, D.C., 1975, 1975. Gelatin silver print; mat: 16 x 20 in. (40.6 x 50.8 cm). Collection Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago, Illinois Arts Council Purchase Grant, 1980.12

Photo: Nathan Keay © MCA ChicagoUntitled (History of Photography Series), 1991

Kenneth Josephson, Untitled (History of Photography Series), 1991, 1991. Gelatin silver print; 12 7/16 x 9 11/16 in. (31.6 x 24.6 cm). Courtesy of the artist Stephen Daiter Gallery, Chicago

The Sun Is Always Setting Somewhere Else

Lisa Oppenheim, The Sun is Always Setting Somewhere Else, 2006. Slide projection of 15 color 35 mm slides, continuous loop, edition of 4, aside from one artist's proof; overall dimensions variable. Collection Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York. Courtesy of the artist and Tanya Bonakdar Gallery, New York

New York State, 1970

Kenneth Josephson, New York State, 1970, 1970. Gelatin silver print; framed: 17 × 21 in. (43.2 × 53.3 cm). Collection Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago, gift of Katherine S. Schamberg by exchange, 2014.4

Photo: Nathan Keay © MCA ChicagoComparative image

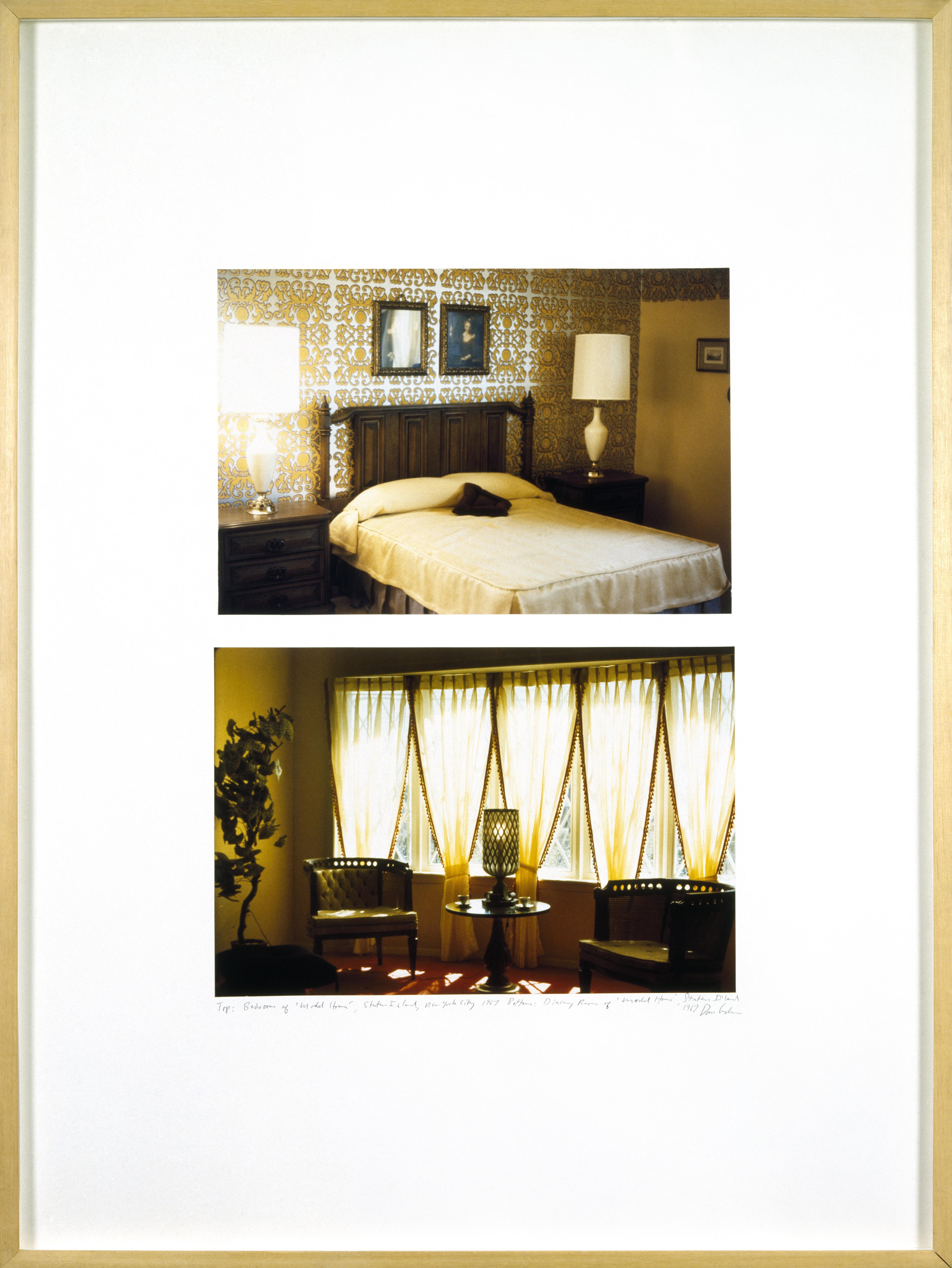

Dan Graham, Bedroom Dining Room Model House, 1967. Chromogenic development prints; sheet: 37 3/4 x 27 5/8 in. (95.9 ?x 70.2 cm), frame: 38 7/8 x 28 7/8 in. (98.7 x 73.3 cm). Collection Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago, Gerald S. Elliott Collection, 1995.42

Photo © MCA ChicagoCredits

Funding

This website is published on the occasion of the exhibition Picture Fiction: Kenneth Josephson and Contemporary Photography, on view Apr 28–Dec 30, 2018, at the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago.

'find' cannot be located

Problem in Kenneth Josephson page: Edit

Picture Fiction: Kenneth Josephson and Contemporary Photography is part of Art Design Chicago, an initiative of the Terra Foundation for American Art exploring Chicago's art and design legacy, with presenting partner The Richard H. Driehaus Foundation.

Picture Fiction is made possible through support from the Terra Foundation for American Art.

Generous support is provided by the David C. and Sarajean Ruttenberg Arts Foundation, Suzette Bross and Allen E. Bulley, III, and Farrow & Ball.

Website

This website has been produced by the Design, Publishing, and New Media Department of the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago in collaboration with the Department of Rights and Images, Curatorial Department, and Library. It is built using the MCA's web content management system.

Design: Alexander Shoup

Editorial: Shauna Skalitzky

Typeface created by Karl Nawrot

- CHIEF CONTENT OFFICER

- Susan Chun

- DIRECTOR OF DIGITAL MEDIA

- Anna Chiaretta Lavatelli

- INTERIM DESIGN DIRECTOR

- Gabriel Melcher

- SENIOR EDITOR

- Sheila Majumdar

- WEB DEVELOPER

- Alexander Shoup

- WEB CONTENT MANAGER AND EDITOR

- Shauna Skalitzky

- PRODUCTION DESIGNER

- Dorothy Lin

- ASSOCIATE VIDEO PRODUCER

- Bridget O’Carroll

- ASSOCIATE EDITOR

- Leah Froats

- MANAGER OF PLANNING AND PRODUCTION

- Lorenzo Conte

- DESIGN AND PUBLISHING ADMINISTRATIVE ASSISTANT

- Christina Stephens

- MANAGER OF RIGHTS AND IMAGES

- Bonnie Rosenberg

- RIGHTS AND IMAGES ASSISTANT

- Elyssa Lange

- JAMES W. ALSDORF CHIEF CURATOR

- Michael Darling

- ADJUNCT CURATOR

- Lynne Warren

- FORMER CURATORIAL RESEARCH FELLOW

- Lauren Fulton

- CURATORIAL ASSISTANT

- Molly Brandt

- DIRECTOR OF LIBRARY AND MUSEUM SERVICES

- Mary Richardson

- LIBRARIAN AND ARCHIVIST

- Erin Matson

Landing page: Kenneth Josephson, Chicago, 1973, 1973. Gelatin silver print; 6 1/32 x 9 1/16 in. (15.3 x 23 cm). Courtesy of Stephen Daiter Gallery, Chicago.

Images found on this site are for educational use and are published under the umbrella of the Fair Use doctrine.