Chicago Works:

Deborah Stratman

This digital brochure was published on the occasion of the exhibition Chicago Works: Deborah Stratman, organized by Jack Schneider, Curatorial Assistant. It is presented in the Dr. Paul and Dorie Sternberg Family Gallery and Ed and Jackie Rabin Gallery on the museum's third floor.

Vox Terra: On Deborah Stratman's The Illinois Parables Suite

Written by Jack Schneider

“Let’s face it. What counts is knowledge. And feeling. You see, there is such a thing as feeling tone. One is friendly and one is hostile. And if you don’t have this, baby, you’ve had it. You’re dead.”

—Nancy Dickerson in Studs Terkel’s Division Street: America

I

Deborah Stratman, Opening shot of The Illinois Parables, 2016. 16mm film or DCP; 60 min. Image courtesy of the artist.

Deborah Stratman's The Illinois Parables (2016) opens with a panoramic shot, the camera floating above a great plain. Winding roads and rivers cross rectilinear patches of grey, green, and brown vegetation. This birds'-eye view marks the beginning of Stratman's expansive film, which is the focus of the artist and filmmaker's exhibition, Chicago Works: Deborah Stratman, at the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago.

Across eleven chapters (or "parables"), Stratman chronicled the history of the state, guided by an understanding that people are not separate from the environment but are part of it. In making the film Stratman traveled to what she describes as "thin" places, sites where the depth of history is palpable, where the boundary between present and past—as well as nature and culture—is indeed thin. The Parables can be understood as a case study of the so-called Anthropocene, the proposed geological epoch wherein humans have become the primary force changing the Earth's landscapelink. Throughout, Stratman's film shows how people have marked the landscape of present-day Illinois, her home state, and how this landscape has in turn marked those who have called it home.

On the occasion of the MCA exhibition, Stratman created an extension of the film—a twelfth chapter, annex, or coda—in the form of a sculptural installation and audio program titled Feeling Tone (2020). The installation is a replica of Louis "Studs" Terkel's radio booth from the WFMT headquarters in downtown Chicago and is accompanied by a selection of 143 of the oral historian's interviews. With Feeling Tone, Stratman layered a multitude of voices atop the landscape seen in The Illinois Parables, prompting us to consider the land not simply as a physical object but also as a collection of subjectivities. While broad in scope, between the film and audio program, Stratman's historical account of the land known as Illinois is still necessarily a partial one—an eclectic and idiosyncratic anthology of stories. In this essay, I will briefly summarize each chapter of The Illinois Parables, analyzing individual shots and unpacking Stratman's historical references, and conclude by considering how Feeling Tone expands upon the topics and themes of the film.

Deborah Stratman, Cahokia Mounds as seen in The Illinois Parables, 2016. 16mm film or DCP; 60 min. Image courtesy of the artist.

One of the first images we see in chapter I is a grand earthen mound, shot from an asphalt lot with the banal outlines of parking spots bisecting the frame. Like a palimpsest, the marks of paved roadways overwrite the marks left on the landscape by some of Illinois' Indigenous inhabitants: the Mississippians. In chapter I, Stratman focused on what remains of the Mississippian's civilization in the landscape; namely, the Cahokia Mounds. Estimates place the ancient city's population between 1150 and 1200 AD in the tens of thousands, by some accounts larger than contemporaneous London and Paris link link. Central Cahokia's architecture consisted of more than one hundred rammed-earth mounds, several of which we see in Stratman's film, laid out over approximately six square miles near Horseshoe Lake in what is now southwestern Illinois. Cahokia served as an economic, political, and cultural center for Mississippians who lived throughout the region. link Cahokia's population began to decrease in the thirteenth century, and while the reason for this change is unknown, one recent hypothesis suggest that climatic shifts resulted in increased flooding in the region, disrupting Cahokia's agricultural systems. link The site's current name comes from the Cahokia, an Illinois Confederacy (Illiniwek) tribe that lived in the area at the time when French settler-colonial explorers arrived in the seventeenth century. link Across the first three chapters of her film, Stratman shows how the American landscape is inextricably entangled with its settler-colonial history.

II

Deborah Stratman, Still from The Illinois Parables, 2016. 16 mm film or DCP; 60 min. Image courtesy of the artist.

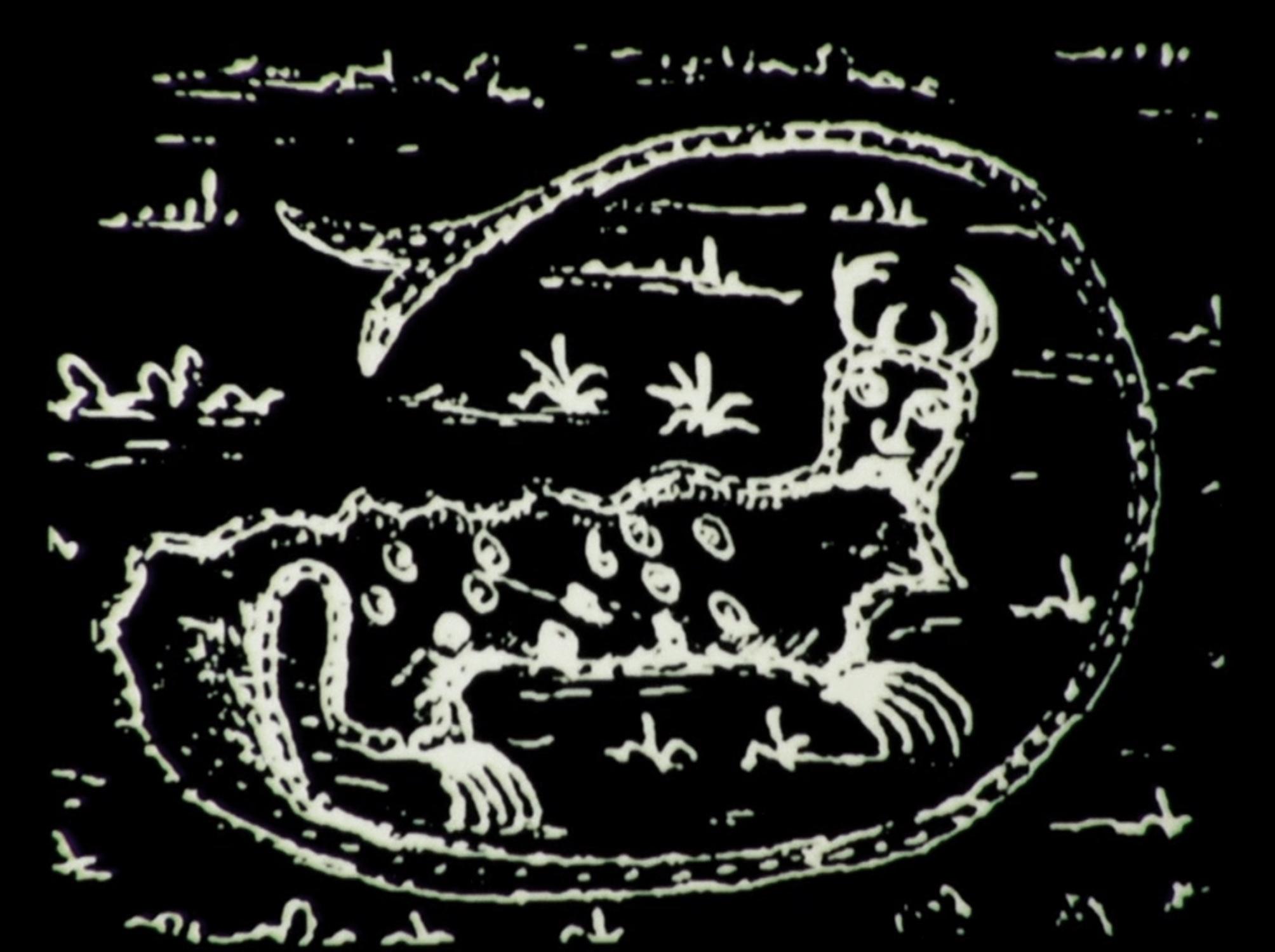

Deborah Stratman, Louis Joliet's sketch of the mural and an amateur restoration of the mural in Alton, IL, as seen in The Illinois Parables, 2016. 16mm film or DCP; 60 min. Image courtesy of the artist.

Inasmuch as The Illinois Parables is an examination of a history-laden landscape, it is also an examination of historicity—or the authenticity of representations of the past. In chapter II, Stratman presents a montage of several historic documents that ostensibly depict the same thing but at times contradict one another, calling their authenticity into question. At the outset of this chapter, we see a sketch made by French settler-colonial explorer Louis Joliet. The sketch documents a mural of a composite, chimera-like creature painted on a limestone bluff. Joliet and Jacques Marquette encountered the mural on their 1673 expedition down the Mississippi River. In a journal description, which Stratman included as a voiceover in her film, Marquette described the sight:

They are as large As a calf; they have Horns on their heads Like those of a deer, a horrible look, red eyes, a beard Like a tiger’s, a face somewhat like a man’s, a body Covered with scales, and so Long A tail that it winds all around the Body, passing above the head and going back between the legs, ending in a Fish’s tail.

In Stratman's film, Joliet's sketch is followed by an image of the present-day historical site in Alton, Illinois, which includes a crude re-creation of the original mural. This re-creation differs from Joliet's sketch and Marquette's description in numerous ways: most notably, the creature has sprouted wings. In an 1863 publication, Alton resident John Russel popularized the idea that the original mural depicted a Piasa, which according to Russel's fabricated account was a "bird that devours men" in Illiniwek folklore. link However, the wingless creature depicted in Joliet's sketch of the original mural is in fact far more consistent with Anishinaabe iconography of the underwater panther, a supernatural being that lives in the deepest parts of lakes and rivers. linklink. Regardless of the historical inaccuracy, today the mural is popularly known as the Piasa Bird. In chapter II of the Parables, we see how multiple layers of historical interpretation—by settler-colonial invaders, fraudulent storytellers, and amateur conservationists—amounts to a misunderstanding of the original mural. This is one specific example of the systemic misrepresentation of Indigenous peoples and their cultures. link

III

Chapter III opens at the Illinois State Museum in Springfield, where we see dioramas with dusty, plasticky, life-size replicas of plants, animals, and people against trompe-l’oeil painted backdrops. While intended as a tool to educate about the land's Indigenous peoples, the exhibit incorrectly suggests that the people and culture on display are gone—as evidenced by the exhibit's title Peoples of the Past.link These dioramas, which debuted at the Museum in 1984, follow a familiar format for the display and collecting of sacred Native American materials at museums throughout the United States. link The violence of such exhibits is their symbolic erasure of contemporary Indigenous peoples, descendants of these "peoples of the past," who continue to live throughout the state, the country, and the world despite ongoing settler-colonial subjugation. link link link Furthermore, these displays—especially when presented in the context of natural history museums—ontologically position Indigenous peoples alongside animals and plants. These groups then are set opposite Western people on the archaic nature vs. culture divide, effectively reifying the racist colonial distinction between "savage" and "civilized" societies. link link

Deborah Stratman, A diorama at the Illinois State Museum in Springfield, IL as seen in Deborah Stratman's The Illinois Parables, 2016. 16mm film or DCP; 60 min. Image courtesy of the artist.

This racist worldview served as justification for a wide array of atrocities throughout US history. Ponca scholar Roger Buffalohead discussed the myth of the “savage” in an interview with Studs Terkel—one of the interviews that Stratman included in Feeling Tone (2020). Buffalohead said, "The myth served a function in American society as it developed, it provided a rationale for the dispossession of Indians of their lands." Part of this larger history of dispossession is the United States government's forced removal of Cherokee people from their ancestral homelands, across the Midwest to Indian Territory in present-day Oklahoma. Stratman addressed this United States–sanctioned genocide in chapter III.

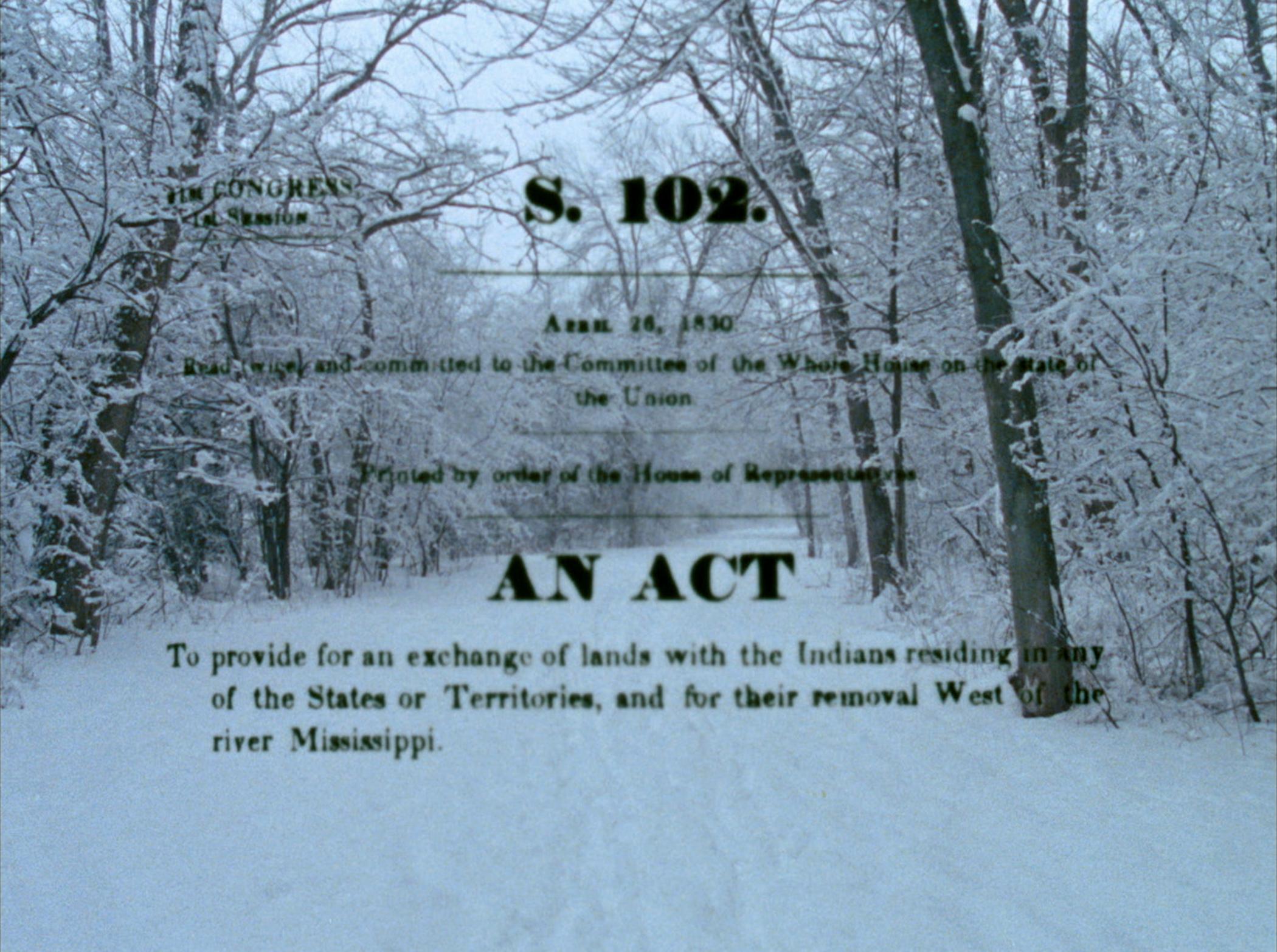

Deborah Stratman still from The Illinois Parables, 2016 16mm film or DCP 60 min. Image courtesy of the artist

Driven by ideologies of American exceptionalism and rumors of gold, in the early nineteenth century the state of Georgia sought to extend their rule over Cherokee territory in order to allow white miners to settle there. The Cherokee responded with legal action against the state link. In a ruling on the Cherokee's second case argued by the Supreme Court, Worcester v. Georgia (1832), Chief Justice John Marshall's decision affirmed the legitimacy of existing Cherokee treaties with the United States and denounced Georgia's legislation over the Cherokee as unconstitutional. 10 Recounting the event in an interview with Studs Terkel—which Stratman includes in Feeling Tone—Dakota scholar and activist Vine Deloria Jr noted, “When John Marshall made the decision that the United States had to guarantee the political existence of the Cherokees, [President] Andrew Jackson just said, 'Well, he's made his decision, let him enforce it.'" Empowered by the Indian Removal Act of 1830—a portion of which Stratman includes as an intertitle in her film—Jackson refused Marshall's mandate to uphold existing treaties with the Cherokee and proceeded to ratify the Treaty of New Echota in 1836. 11 The new treaty gave Cherokee people two years to leave their ancestral homelands, despite the fact that neither Cherokee leadership nor the vast majority of Cherokee people signed or supported it. As most Cherokee understood the treaty to be illegitimate, most remained. In 1838 7,000 US troops invaded their land, marking the beginning of what the Cherokee call "Nunna daul Tsuny," which translates to “the trail where they cried,” and has become known as the Trail of Tears. 12

IIII

Deborah Stratman, Still from The Illinois Parables, 2016. 16 mm film or DCP; 60 min. Image courtesy of the artist.

Deborah Stratman, Trail of Tears Road as seen in The Illinois Parables, 2016. 16mm film or DCP; 60 min. Image courtesy of the artist.

While making the Parables, Stratman visited sites along the westward route US soldiers forcibly marched Cherokee people on, such as Golconda, the town where Cherokee people crossed the Ohio River into Illinois on December 3, 1838. In the film, we see a depiction of this event in a mural painted on a levee in Golconda. Elsewhere in chapter III, we see a road sign that reads “Trade of Tears Rd,” marking how portions of the historic route have been inscribed with concrete and asphalt into the landscape. Stratman also includes shots of snow-covered expanses, alluding to the particularly frigid winter the Cherokee suffered through 178 years ago on their forced march across the Midwest. Many of the 4,000–8,000 deaths that occurred along the Trail of Tears due to exposure, disease, starvation, and wounds inflicted by US soldiers happened in the three months Cherokee people spent crossing Illinois.13

Stratman uses historical documents and the marked traces of the Trail of Tears in the landscape to tell this story of genocide. That said, she did not consult members of the three contemporary Cherokee tribes—the United Keetoowah Band of Cherokee Indians, the Cherokee Nation, and the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians14—while creating her film. The Trail of Tears is part of the ongoing systemic dispossession of Indigenous peoples perpetuated by the United States government. While Stratman does not include it in her film, the Trail of Death tells another part of this story, wherein Potawatomi people were violently removed from their lands in present-day Indiana and forced to move hundreds of miles westward, passing through present-day Illinois, Missouri, and Kansas, leading to dozens of deaths.15 Present-day Illinois is situated within the ancestral homelands of many Native nations, including the Council of Three Fires (Potawatomi, Ojibwe, Odawa), Ho-Chunk, Menominee, Meskawki, Sauk, Miami, Wea, Piankashaw, Kickapoo, Illinois Confederacy, Peoria, and Shawnee. Members of these nations and more continue to live and thrive throughout Illinois.16

IV–V

Deborah Stratman, Still from The Illinois Parables, 2016. 16 mm film or DCP; 60 min. Image courtesy of the artist.

Deborah Stratman, Carl Christian Anton Christensen's painting Burning of the Temple (c. 1878) and the rebuilt Mormon Temple in Nauvoo as seen in The Illinois Parables, 2016. 16mm film or DCP; 60 min. Image courtesy of the artist.

Throughout her film, Stratman shows how present-day Illinois is contested territory. Chapter IV of the Parables tells the story of a group of white settlers: the Church of Latter-day Saints in Nauvoo, Illinois. Nauvoo was founded by Mormon prophet Joseph Smith Jr. as a refuge following the Mormon War of 1838, which forced the church and its people out of Missouri. By 1845, the population of Nauvoo had ballooned to an estimated 12,000 people, about the size of contemporaneous Chicago. According to local historians Elder Everest and Sister Everest, whose account is included as voiceover in the film, around this time the Mormons began voting as a bloc which "began to take the accustomed political power of the old settlers of Hancock county away from them, and that aroused more than just curiosity, that aroused anger." Anti-Mormon sentiment flared in neighboring communities and church leaders were jailed in nearby Carthage, Illinois. Shortly thereafter an angry mob stormed the jail, assassinating Smith and his brother.

Following the assassination of Smith, arsonists burned buildings throughout Nauvoo, including the Mormon temple which is illustrated in the Parables with C. C. A. Christensen’s (Danish, 1831–1912) painting Burning of the Temple (c. 1878). By 1846, the Mormons were forced out of Nauvoo. A century and a half later in 2003, the Mormons rebuilt their temple.

As the Mormons departed, they left a political and spatial vacuum in their wake—chapter V tells the story of those who filled it. Two years after the Mormons left Nauvoo, a contingent of French colonists led by political theorist Etienne Cabet settled in the town. Cabet renamed it Icaria after the fictional utopian society he wrote about in his 1840 novel The Voyage to Icaria. Cabet’s novel described a society wherein all things were shared communally, including property and food; even children were raised collectively by the community. Icaria was to be the real-world manifestation of Cabet’s dream society.

While the Icarians successfully developed a functional society, their population never reached the numbers that their Mormon predecessors had. Despite their unusual ideas and values, they never became a serious political threat to the neighboring communities the way the Mormons had. Rather than being forced out, the demise of the Icarians was due to internal discord.

VI–VIII

While many historical accounts might consider land to be an inert stage upon which struggles between human actors play out, in the Parables Stratman shows that nonhuman forces are not to be discounted as active agents in shaping history. This is most evident in chapter VI, which describes the Tri-State Tornado, a mile-wide monster that tore through southwestern Missouri, southern Illinois, and southwestern Indiana in 1925. Archival footage of the aftermath included in the Parables shows how the tornado scraped across the landscape, destroying nearly everything in its path. A voiceover of a woman describes how her pet parrot was found perched upon the ruins of her former home, covered in soot "as black a crow" and singing the hymn "Sweet Hour of Prayer," a version of which Stratman also included in the film. The disaster claimed the lives of over 800 people and left 15,000 more homeless. It was a karmic dispossession of life and land by the nonhuman force of the weather.

A tornado is a particularly explicit—and particularly Midwestern—example of how nonhuman forces shape history. But nonhuman forces govern our lives from the macrocosmic scale of weather and climate to the microcosmic scale of atomic physics. Chapter VII of the Parables focuses on how the Atomic Age began with an experiment in Illinois.

Featured images

Deborah Stratman, Archival footage showing the aftermath of the 1925 Tri-State Tornado as seen in The Illinois Parables, 2016. 16mm film or DCP; 60 min. Image courtesy of the artist.

Deborah Stratman, Archival footage showing the aftermath of the 1925 Tri-State Tornado as seen in The Illinois Parables, 2016. 16mm film or DCP; 60 min. Image courtesy of the artist.

Deborah Stratman, Archival footage showing the aftermath of the 1925 Tri-State Tornado as seen in The Illinois Parables, 2016. 16mm film or DCP; 60 min. Image courtesy of the artist.

VII

In the Parables we see a series of stone markers from the United States Department of Energy in the Red Gate Woods of southwestern Chicago. Part commemorative plaque and part warning sign, the markers tell the story of Chicago Pile-1, the reactor that created the first sustained artificial nuclear chain reaction. The reaction occurred at the University of Chicago in 1942, under the direction of American-Italian physicist Enrico Fermi. Audio included in the Parables from a 1960s educational film describes the experiment in utopian terms: "CP-1: The Day Tomorrow Began." The experiments were a crucial step in the Manhattan Project, the US government's effort to develop nuclear weapons during World War II. The markers in Red Gate Woods note that potentially dangerous radioactive remains from CP-1, as well as the subsequent CP-2 and CP-3 reactors, are buried at the site.

Tellingly, the words of warning carved into the stones are only in English, as if their creators couldn’t imagine a future where non–English speaking people would encounter the site. But if there’s any lesson to take away from Stratman’s film, it’s that in a country marred by the ongoing legacy of colonialism, inhabitancy isn’t fixed. With the existential threats of climate change and a renewed nuclear arms race, the likelihood of this particular ruin outlasting Western civilization seems more than possible. While nothing is truly permanent, the materials buried at the site are remarkably close—at least from a human perspective. Some of the nuclear waste buried here will remain radioactive for at least 24,000 years.

The initial optimism over the so-called Atomic Age mutated into pessimism and paranoia following the United States' bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in Japan, the Cuban Missile Crisis, and the nuclear meltdown at Chernobyl, among other events. In the Parables we see evidence of ongoing nuclear suspicion in an act of vandalism on one of the stone markers: the word "no" has been chipped out of the sentence "There is no danger to visitors."

Deborah Stratman, Stone marker in Red Gate Woods as seen in The Illinois Parables, 2016. 16mm film or DCP; 60 min. Image courtesy of the artist.

VIII

From the burial site of CP-1, Stratman moved to another military-industrial graveyard. In chapter VIII we see a series of small hills popping out of the otherwise characteristically flat Midwestern landscape. These mounds are, in fact, ruins from the former Joliet Army Ammunition Plant, a military facility that produced explosives during World War II, the Korean War, and the Vietnam War. In 1996, the area became the Midewin National Tallgrass Prairie, the country's largest prairie reserve, named after the Potawatomi word for "healer." From the end of the last ice age roughly 13,800 years ago, prairies covered 60% of Illinois and supported a biodiverse ecosystem. The arrival of settler-colonial invaders some four hundred years ago marked the beginning of the rapid transformation of the land, which was thoroughly reorganized under the logic of capitalism to become a patchwork of mostly privately owned lands used for agricultural, industrial, and residential purposes. Because of this, Illinois has lost 99.999% of its prairieland.17 Midewin is an essential project as a refuge for numerous rare and endangered nonhuman animal and plant species, such as Upland sandpipers, Eastern Prairie Fringed Orchids, and Blanding's turtles.18 Midewin can also be understood in the larger historical context of the racist conservation movement, which privileges the existence and livelihood of animals and plants while disregarding the many Indigenous peoples who have and will continue to call this land home.19

Deborah Stratman, Still from The Illinois Parables, 2016. 16mm film or DCP; 60 min. Image courtesy of the artist.

IX

Deborah Stratman, Reenactment of the mysterious fires at the Willey Farm in Macomb, IL as seen in The Illinois Parables, 2016. 16mm film or DCP; 60 min. Image courtesy of the artist.

Deborah Stratman, Still from The Illinois Parables, 2016. 16 mm film or DCP; 60 min. Image courtesy of the artist.

While things beyond what we might consider "natural" are addressed throughout Stratman's film, chapter IX takes a distinctively supernatural turn. In the summer of 1946, a series of mysterious fires broke out on a farm in Macomb, Illinois. The blazes started out small: little brown spots on the farmhouse walls that smoldered for several minutes before bursting into flames. In the following weeks, hundreds of small fires inexplicably broke out around the property—one of which burnt out of control, destroying the farmhouse before fire trucks arrived. By this point, the mystery fires were big news; even the United States Air Force was brought in to investigate, but they left just as baffled as everyone else. One theory claimed concentrated radioactivity caused the fires—more evidence of America's Atomic Age paranoia.

Another popular theory centered on a thirteen-year-old girl named Wanet MacNeill who lived on the farm, Stratman dramatizes this theory in the film. It was suggested that MacNeill was pyrokinetic, causing the fires solely with the power of her mind. The actual cause turned out to be far more banal. MacNeill eventually confessed under pressure to starting the fires with kitchen matches while no one was looking, stating dissatisfaction with her life on the farm as reason for the arson. The explanation satisfied authorities and reporters; however, to this day paranormal investigators remain unconvinced. In the Parables Stratman seemed to side with the skeptics.

Stratman's inclusion of MacNeill's story in the Parables speaks to the multitude of smaller, personal-scale stories that cumulatively shape landscapes everywhere.

X

Deborah Stratman, Still from The Illinois Parables, 2016. 16 mm film or DCP; 60 min. Image courtesy of the artist

In chapter X we see how life in America is especially precarious when one’s worldview or way of life challenges those in power. The film’s penultimate chapter recounts the case of the police raid of the Chicago Black Panther Headquarters in 1969. The event was a culminating moment in a decade of tension between insurgent political movements and the United States government.

In the early morning of December 4, 1969, the Chicago Police Department (CPD) entered the Panther headquarters at 2337 W. Monroe Street, killing two people and wounding several others. In the Parables a voiceover describes the CPD's version of events: they engaged in a "gun battle," initiated by the Panthers, while executing a search warrant on the property. However, out of nearly one hundred bullets fired that morning, only one was ultimately determined to have come from inside the building. Over the course of the ensuing thirteen-year legal battle, it was revealed that the police worked with the FBI to orchestrate the raid, specifically with an agent provocateur and informant named William O'Neal who had infiltrated the Panthers. 20

FBI memos included as intertitles in the Parables reveal the Bureau considered the Panthers to be a "black nationalist hate group," which the FBI sought to neutralize by launching the operation known internally as COINTELPRO. Of particular concern to the agency was the rise of a "messiah" that would catalyze people around the growing political movement. The December 4 raid was designed to neutralize one such messianic figure: Fred Hampton, the young charismatic Chairman of the Chicago Panthers who was killed in his sleep during the raid. Hampton, who was 21 years old at the time of his death, was a rising leader and revolutionary socialist who helped form the Rainbow Coalition, a multicultural organization that brought together Black, Latino, Indigenous, and white working-class people across Chicago to fight police brutality, gentrification, and systemic racism. Hampton's assassination by the US government is a potent reminder of the lengths those in power will go to suppress philosophies contrary to their own. In closing the chapter, we see a mural of Hampton at 2746 W. Madison Street, a physical marker in the urban landscape of his lasting influence and the ongoing legacy of Black radical politics.

XI

Deborah Stratman, Michael Heizer's Effigy Tumuli as seen in The Illinois Parables, 2016. 16mm film or DCP; 60 min. Image courtesy of the artist.

Deborah Stratman, Michael Heizer's Effigy Tumuli as seen in The Illinois Parables, 2016. 16mm film or DCP; 60 min. Image courtesy of the artist.

Following ten earthbound chapters, in the final chapter Stratman again traveled skyward via hot air balloon, mirroring the opening shot of the film's prologue, to film Michael Heizer’s (American, b. 1944) monumental earthwork Effigy Tumuli (1983–85) in Buffalo Rock State Park. Visually, Effigy Tumuli recalls the earthen mounds of Cahokia pictured in the first chapter of Stratman's film. By bracketing her film with the Cahokia mounds in the beginning and Heizer's curious pastiche of Indigenous mound-building cultures in the end, Stratman calls into question the relationship between the two sites. The title of Heizer's artwork references effigy mounds, raised earth structures shaped into the forms of animals and other figures (perhaps the most widely known is the Great Serpent Mound in present-day Ohio created by the Adena people). 21Consistent with the basic visual forms of effigy mounds, Effigy Tumuli depicts several nonhuman animal and plant species endemic to the area, including a catfish, turtle, frog, and snake, as well as a water strider, which we see in Stratman's film. Heizer's title also references tumuli, which are raised earth structures that, like many effigy mounds, contain sacred burial remains. Effigy Tumuli, though, is a misrepresentation of the form, as it contains no such remains. Heizer solely adopted the aesthetic dimensions of effigy mounds and tumuli to create his artwork, evidencing a misunderstanding of the multiple purposes these structures serve for the people who made them.

Art historically, Heizer is often cited as a “pioneer” of so-called land art, a title which denies the long history of Indigenous earthworks in order to position him as the progenitor of a “new” kind of art. 22 23 Speaking on Effigy Tumuli, Heizer said, “It was my chance to make a statement for the Native Americans.” As there is a lack of critical scholarship on Heizer's interest in and appropriation of Indigenous visual cultures, what the particular statement is remains unclear. 24 Heizer's general interest in earthworks is their ability to carry information through time by embedding it in the landscape. In Heizer's words, "[A]rt is a record of civilization and its societies [. . .] As time goes by what interests us will interest those who will examine our historical time." 25 Perhaps Heizer's speculative audience of future historians will take interest in Effigy Tumuli as an example of a time when American artists were interested in appropriating Indigenous visual cultures while their country continued to subjugate Indigenous peoples.

Heizer seemed to be interested in historicizing his artwork in relation to Indigenous earthworks. However, Heizer's historical context and positionality, as a contemporary white non-Native artist working in the lineage of modernism, is entirely disconnected from that of the Indigenous mound-building cultures whose effigy mounds and tumuli he mimics. Beyond simple formal similarities, Heizer's artwork has little relation to Indigenous land-based cultural practices. As with the Illinois State Museum's display depicted in chapter III of Stratman's film, we can understand Effigy Tumuli as contributing to the ongoing and systemic misrepresentation of Indigenous peoples and cultures.

XII

Stratman described the process of winnowing down the stories included in the Parables as "somewhat tortuous." 26 The complex history of any place simply cannot be told by a finite number of stories—especially in a one-hour film. Recognizing this, Stratman created Feeling Tone (2020), a sculptural installation and audio program which expands upon the stories included in the film through a multitude of voices. The replica of Studs Terkel's WFMT radio booth is complete with furniture, recording equipment, and ephemera, some of which came directly from WFMT's archives. The exterior of the structure is left raw: with wood studs, drywall, and electrical wiring exposed as if the booth was ripped from the WFMT headquarters and transported to the gallery intact.

Installation view, Chicago Works: Deborah Stratman MCA Chicago

Louis "Studs" Terkel was a renowned broadcaster, oral historian, activist, and Pulitzer Prize–winning author who made a name for himself with his books such as Division Street: America and his radio show which ran on WFMT for forty-five years. Terkel conducted interviews with a diverse array of luminaries such as James Baldwin, Maya Angelou, and Cesar Chavez, to name just a few, but also with people he affectionately referred to as "the etceteras": the everyday working people of Chicago, Illinois, and beyond. It was in an interview with one such etcetera, a hospital worker named Nancy Dickerson, that Terkel was introduced the idea of the "feeling tone." 27 For Terkel, feeling tone is raw emotional experience, expressed in the sonic character of a storyteller's voice, found not in facts and figures but in inflection and timbre.

Over the course of his career, Terkel amassed over 9,000 hours of recorded interviews. He christened his archive—the totality of his life's work—Vox Humana: The Human Voice.28 For her installation, Stratman chose one interview from Terkel's Vox Humana to play each day of the exhibition. There are 143 interviews in total, a dated list can be found here. Stratman envisions her installation as a spaceship, transporting museum visitors through time and space on the sonic wavelengths of voices.

Installation view, Chicago Works: Deborah Stratman MCA Chicago

Politically Terkel had socialist leanings and advocated for numerous social causes throughout his life, including civil rights, feminism, LGBTQ rights, and environmentalism. The invention of telecommunications allowed for the capitalist reorganization of nature to extend beyond the landscape and into the airspace, where radio frequencies have been regulated by governmental bodies and sold off to the highest bidders. However, within this privatized airspace, public radio stations like WFMT mostly remain spaces of free thought and expression, uninhibited by corporate interests—like public parks in the sky. As with all media, it's important to consider the motives behind the dissemination of information: in Stratman's words, "We need to care about how the world gets delivered to us."

History can feel objective, distant, and impersonal. In history textbooks, groups of people are often presented as abstractions or statistics through the distant voice of historians. With The Illinois Parables and its sculptural extension Feeling Tone, Stratman offered a different kind of history. She shows how the landscape is an earthen record, containing the marks and scars left by its shifting inhabitants and the ongoing legacies of settler-colonialism, racism, militarism, and capitalism—ranging from mounds, roads, and buildings to ruins and radioactive waste. These physical traces, left behind by humans, are the hallmarks of the Anthropocene, but Stratman also asks us to consider this complex, human-wrought landscape as more than just geology. To truly understand the land, you can't just look. You must also listen. Between the film and installation, Stratman layered music, archival audio, ambient sounds, and the voices of the land's inhabitants within the landscape, reflecting not just a history of Illinois but a particular feeling tone of the land.

Footnotes

- The political implications of the Anthropocene have been debated widely in recent years; for example, the universal framing of humanity (anthopos) on a species level has been criticized for overlooking the ways specific groups of people have subjugated others throughout human history. For an introduction to these debates, see Harraway, Donna, Making Kin: Anthropocene, Capitalocene, Plantationocene, Cthulucene. read.dukeupress.edu/environmental-humanities/article/6/1/159/8110/Anthropocene-Capitalocene-Plantationocene; Yusoff, Kathryn. A Billion Black Anthropocenes or None. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 2018; Todd, Zoe. "Indigenizing the anthropocene." Art in the Anthropocene: Encounters among aesthetics, politics, environments and epistemologies (2015): 241–54.; and Demos, T. J., Against the Anthropocene: Visual Culture and Environment Today. Berlin, DE: Sternberg Press, 2017.

- Kehoe, Alice Beck. "Cahokia, the Great City." OAH Magazine of History 27, no. 4 (2013): 17–21. Accessed December 3, 2020. jstor.org/stable/43797866.

- White, A. J., Samuel E. Munoz, Sissel Schroeder, and Lora R. Stevens. "After Cahokia: Indigenous Repopulation and Depopulation of the Horseshoe Lake Watershed AD 1400–1900." American Antiquity 85, no. 2 (2020).

- Holt, Julie Zimmermann. "Rethinking the Ramey State: Was Cahokia the Center of a Theater State?" American Antiquity 74, no. 2 (2009): 231–54. Accessed December 6, 2020. jstor.org/stable/20622425.

- Munoz, Samuel E., Kristine E. Gruley, Ashtin Massie, David A. Fike, Sissel Schroeder, and John W. Williams. "Cahokia's Emergence and Decline Coincided with Shifts of Flood Frequency on the Mississippi River." Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 112, no. 20 (2015).

- The Cahokia were part of the Illinois Confederacy (also Illini, Illiniwek), which also included the Peoria, Kaskaskia, Tamaroa, Moingwena, Tapouaro, Coiracoentanon, Chepoussa, Espeminkia, Chinkoa, Maroa, and Michigamea, and Miami. See, Bilodeau, Christopher. "They Honor Our Lord among Themselves in Their Own Way: Colonial Christianity and the Illinois Indians." American Indian Quarterly 25, no. 3 (2001): 352–77.

- Russell, John. "The Legend of the Piasa." Central States Archaeological Journal 33, no. 4 (1986): 304–07. jstor.org/stable/43139666

- In a presentation for the East Central Illinois Archaeological Society, Duane Esarey unpacks the history of how and why the landmark was misnamed. He also addresses how representations of the original mural have mutated over time and how the actual site of the landmark has shifted due to industrial activity. See Esarey, Duane. January 15, 2015. youtube.com/watch?v=gP2nR_PqIMk

- Costa, David J., George F. Finley, Elizabeth Vallier, and unknown Shawnee Speaker. "Culture-Hero and Trickster Stories ." In Algonquian Spirit: Contemporary Translations of the Algonquian Literatures of North America, edited by Brian Swann, 292–319. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2005.

- Edits to this essay were made after it was originally published in July, 2020, in response to concerns raised by Indigenous community members over how the genocide known as the Trail of Tears was represented, among other issues. Therefore, this essay is another example of the systemic misrepresentation of Indigenous peoples and their cultures in Western scholarship. For a critical examination of the original version of this text, and the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago's historic lack of support for Indigenous artists, see Andrea Carlson's article Where Are The Native Artists at the MCA?: sixtyinchesfromcenter.org/where-are-the-native-artists-at-the-mca/

- illinoisstatemuseum.org/content/peoples-past

- The Field Museum in Chicago is currently renovating their Native North American Hall in collaboration with Native scholars and community members. See fieldmuseum.org/about/press/field-museum-renovate-native-north-america-hall-open-2021

- For an extended critical examination of museum exhibitions focusing on Native American histories, see Lonetree, Amy. Decolonizing Museums: Representing Native America in National and Tribal Museums. Chapel Hill, North Carolina: University of North Carolina Press, 2012.

- Artists Wendy Red Star, James Luna, and Chris Pappan have been instrumental in critical discourse on museum exhibitions that focus on Native American histories and Indigenous peoples.

- Additionally, museums such as the Illinois State Museum that are not tribally controlled or partnered are situated on the ancestral homelands of Native nations they help to dispossess, with their collections serving as repositories for sacred objects and ancestral remains stolen from Indigenous lands.

- Williams, Robert A. Savage Anxieties: the Invention of Western Civilization. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2012.

- In his book Playing Indian, Dakota scholar Philip J. Deloria traces how misconceptions of Indigenous peoples created and used by white Americans have shifted over time, and how these misconceptions relate to racialized social and political systems throughout US history and in the present. See Deloria, Philip Joseph. 1998. Playing Indian. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- With Cherokee Nation v. Georgia (1828), the Cherokee asserted that the state of Georgia's attempt to strip Cherokee people of their rights and displace them from their land violated existing treaties between the United States and Cherokee Nation. The Supreme Court dismissed the case. See supreme.justia.com/cases/federal/us/30/1/

- Ostler, Jeffrey. Surviving Genocide: Native Nations and the United States from the American Revolution to Bleeding Kansas. New Haven; London: Yale University Press, 2019.

- Cave, Alfred A. "Abuse of Power: Andrew Jackson and the Indian Removal Act of 1830." The Historian 65, no. 6 (2003).

- Thornton, Russell. "Cherokee Population Losses during the Trail of Tears: A New Perspective and a New Estimate." Ethnohistory 31, no. 4 (1984): 289–300.

- Ibid.

- While the US government forcibly removed some 16,000 Cherokee people from the southeastern United States during the Trail of Tears, some Cherokee people remained on their land. The Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians presently has 14,000 members, who are in part descended from the hundreds of Cherokee who evaded the Trail of Tears, as well as from Cherokee survivors of the Trail of Tears who returned to the southeast after arriving in Oklahoma. See visitcherokeenc.com/eastern-band-of-the-cherokee.

- John P. Bowes. "American Indian Removal beyond the Removal Act." Native American and Indigenous Studies 1, no. 1 (2014): 65–87.

- Neither this essay nor Stratman's film includes Native perspectives on the lives of contemporary Native peoples. For an extended examination of survivance, a term coined by literary theorist Gerald Robert Vizenor (member of the Minnesota Chippewa Tribe, White Earth Reservation) see his book Vizenor, Gerald Robert. Survivance: Narratives of Native Presence. Lincoln, Neb. University of Nebraska Press, 2009. Survivance is active Native presence and the continuation of Native stories beyond and apart from resistance to settler-colonial subjugation, or as Vizenor described it, "Native survivance is an active sense of presence over absence, deracination, and oblivion."

- See dnr.illinois.gov/conservation/IWAP/Pages/FarmlandandPrairie.aspx

- Greenberg, Joel. A Natural History of the Chicago Region. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2004.

- For a brief history of the racism within the conservation movement see newyorker.com/news/news-desk/environmentalisms-racist-history

- Taylor, Flint. The Torture Machine: Racism and Police Violence in Chicago. Chicago, IL: Haymarket Books, 2019.

- Herrmann, Edward W., G. William Monaghan, William F. Romain, Timothy M. Schilling, Jarrod Burks, Karen L. Leone, Matthew P. Purtill, and Alan C. Tonetti. "A New Multistage Construction Chronology for the Great Serpent Mound, USA." Journal of Archaeological Science 50 (2014): 117–25. doi.org/10.1016/j.jas.2014.07.004.

- For example, see Casey, Edward S., and Edward S. Casey. Earth-Mapping: Artists Reshaping Landscape. Minneapolis, MN: Univ. of Minnesota Press, 2005; newyorker.com/magazine/2016/08/29/michael-heizers-city; and tclf.org/pioneer/michael-heizer

- For a critical discussion of Land Art in relation to Indigenous land-based practices, see Emily Eliza Scott's essay "Decentering Land Art from the Borderlands: A Review of Through the Repellent Fence". artjournal.collegeart.org/?p=9819 33. Heizer, Michael, and Douglas C. MacGill. Effigy Tumuli: the Reemergence of Ancient Mound Building. New York, NY: Abrams, 1990.

- Heizer, Michael, Julia Brown, and Barbara Heizer. Sculpture in Reverse. Los Angeles: Museum of Contemporary Art, 1984.

- filmcomment.com/blog/interview-deborah-stratman/

- Terkel, Studs. Division Street: America. New York: Pantheon Books, 1967

- chicagotribune.com/news/ct-xpm-1997-07-10-9707100137-story.html

Artist Bio

Deborah Stratman (American, b. 1967) is a Chicago-based artist and filmmaker who explores the cycle of influence between people and the land.

Credits and Fine Print

Generous support is provided by the Sandra and Jack Guthman Chicago Works Exhibition Fund.

WEBSITE CREDITS

- DIRECTOR of CONTENT STRATEGY

- Kelsey Campbell-Dollaghan

- CONTENT STRATEGY ASSISTANT

- Nora James

- RIGHTS and IMAGES ASSISTANT

- Elyssa Lange

- EDITOR

- Leah Froats

- CURATORIAL ASSISTANT

- Jack Schneider

- WEB CONTENT MANAGER

- Brontë Marsteller

- PROOFREADER

- Anne Walaszek

- DESIGN and PROGRAMMING

- Alexander Shoup

The Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago is a nonprofit, tax-exempt organization accredited by the American Alliance of Museums. The museum is generously supported by its Board of Trustees; individual and corporate members; private and corporate foundations, including the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation; and government agencies. Programming is partially supported by a grant from the Illinois Arts Council Agency.

Free admission for 18 and under is generously provided by Liz and Eric Lefkofsky.

The MCA is a proud member of Museums in the Park and receives major support from the Chicago Park District.

© 2020 by the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means including photocopy, recording, or any other information-storage-and-retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher.

Images found on this site are for educational use and are published under the umbrella of the Fair Use doctrine.

[Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago]()