Responding to Violence: Salcedo and Cytter

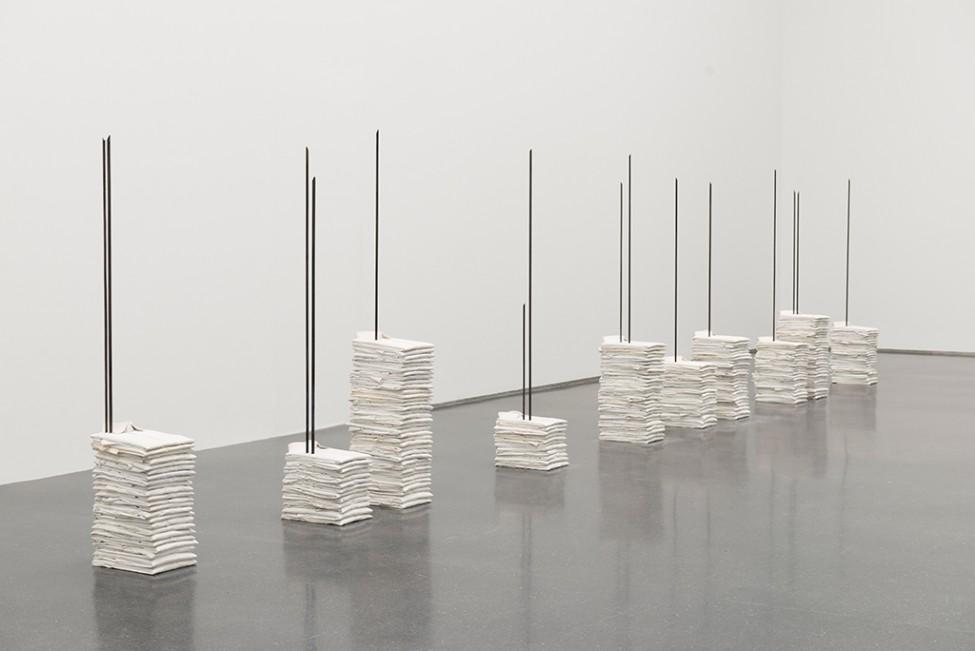

Installation view, Doris Salcedo, MCA Chicago, February 21–May 24, 2015

Photo: Nathan Keay © MCA Chicagoblog intro

With Doris Salcedo’s retrospective closing on Sunday, Editor Michael Kramer compares the work of Salcedo and Keren Cytter, who is currently featured in our Ascendant Artist series. At first, it may seem that these artists and their artwork have little or nothing in common, but Kramer digs into their work a little more deeply to reveal how each artist responds to social problems and violence through their art, though in different ways.

About

Something has gone terribly wrong.

This is where the art of Doris Salcedo and Keren Cytter begins. From there, the work of these two artists, who currently have exhibitions at the MCA, diverges. Salcedo focuses narrowly on specific historical moments of political violence committed against the underprivileged or oppressed; Cytter roams expansively across the vibe and feel of cosmopolitan life in the media-satured worlds of relatively affluent urban dwellers. Salcedo’s tone is somber and earnest; Cytter’s is loopy and irreverent. Salcedo’s materials are mostly sculptural and tangible, even when they reach to outline the contours of the vanished, the lost, the remembered, the murdered. Cytter’s materials are largely intangible. With Salcedo, we experience wooden furniture, cement, cloth, dirt, grass. With Cytter, we experience spliced video, cheap computer effects, recycled movie scripts and plots, doodles on paper.

Video

About

It is worth noting that as with Salcedo, murders occur in Cytter's work too. Violence skims across the surface of much of her artworks while, by contrast, it does something more like haunt Salcedo's sculptural installations from deep within. Cytter reminds us how numb to violence media's stale narrative techniques can make us—how unreal media can make violence feel. Her art evokes Susan Sontag’s argument that photography and other forms of media may seem to publicize violence, but in doing so, they generate apathy more than outrage (or sometimes an apathetic mode of outrage and an outrageous level of apathy). Salcedo's art, in comparison, seeks to pierce through this numbness, to make real even what can never be recovered after political violence: lost love ones, safety and security, bodily and material wholeness. Her work trims away at the excess in search of an intensified core of loss, which in order to be experienced as loss, must also be experienced as survival. Keren Cytter adds and adds to her work in search of an intensified feeling of eerie absurdity. Her videos move, skitter, jump nonsensically. They have action, but the action ultimately seems to be about paralysis, the ways in which plots move forward but we, the spectators, stay in place. Couch potatoes to a killing.

Keren Cytter, Still from Something Happened, 2007. Digital video (color, sound), 7 minutes. Courtesy of the artist and Nagel Draxler, Berlin; Pilar Corrias, London; and Galleria Raffaella Cortese, Milan

About

Salcedo’s work is also about nonsense, the nonsense of political violence, but it attempts to recover some kind of meaning, some register of understanding in the face of slaughter. If Cytter wants to remind us that our normality as dictated by TV shows, films, and digital media barely masks madness, Salcedo suggests that even our most material and basic things—tables, chairs, dressers, shoes, dolls, shirts—terrify but also bring us back to the sanity of the real in the face of the untenably horrible. Both artists ask us to look, and most of all not to look away, in the aftermath of traumas big and small; to sense senselessness; to be a spectator while also questioning what spectatorship involves—and what it demands.

Doris Salcedo, Plegaria Muda (detail), 2008–10. Wood, concrete, earth, and grass; 166 parts, each: 64 5/8 x 84 1/2 x 24 in. (164 x 214 x 61 cm); overall dimensions variable. Installation view, Doris Salcedo, MCA Chicago. Inhotim Collection, Brazil

Photo: Nathan Keay © MCA ChicagoAbout

These are exhibitions that project extremely different tones and put the viewer in almost opposite moods. To get to witness them together at the MCA is a reminder both of how widely very different styles of art can range across shared themes—and also how sometimes they converge on one compelling topic, in this case the pressing issue of how we respond to violence in the modern world.