David Bowie Is Always Evolving

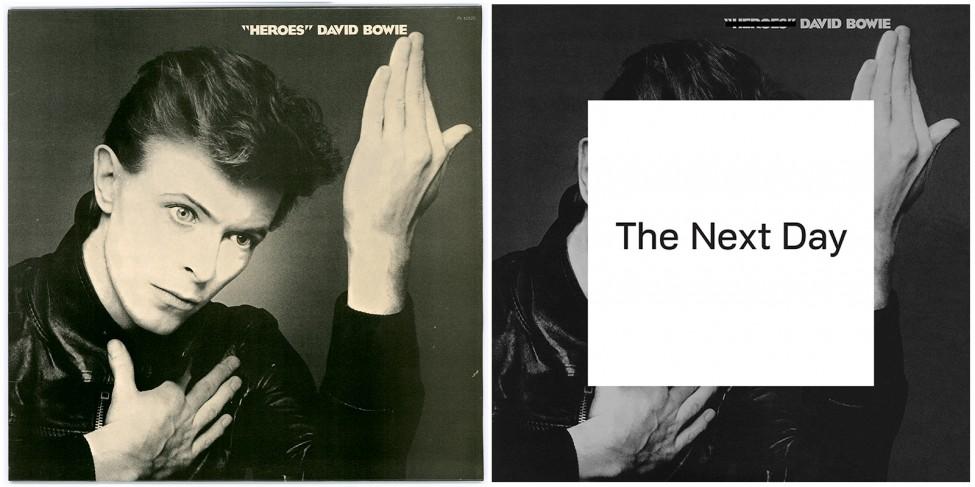

Left: “Heroes” album cover, 1977, Photo: Masatoshi Sukita, Courtesy of the David Bowie Archive

Right: The Next Day album cover, 2013, Cover design: Jonathan Barnbrook, Courtesy of Sony Music Entertainment Inc.

About

In January of 2013, with virtually no advance publicity, David Bowie released The Next Day, his first album in a decade. Not only was the record unexpected since its creation was kept secret, but following the singer's serious heart attack and subsequent surgery in 2004, many assumed he'd retired from music altogether. After decades of relentless reinvention—both musically and visually—he appeared burned-out. In fact, the cover art for The Next Day seemed like a metaphoric admission that Bowie had reached the end of the line as feverish groundbreaker; a white square with the title plainly running across its center was dropped over the original artwork for his brilliant 1978 album “Heroes”, a thick black line through the original album title, as if the singer no longer cared about his image now. The answer might be that the music inside, arguably his finest effort in three decades, summons the spirit of experimentation and emotional torpor of his celebrated Berlin phase in the late 1970s, when he worked with producer Brian Eno.

Between his emergence in the late 1960s and the release of his 1980 classic, Scary Monsters, Bowie and his reserve of ideas—musical and visual—appeared inexhaustible; few musicians have ever delivered such potent and peripatetic work in such a concentrated period. He was an artistic sponge, sucking up the sounds, visions, and ideas all around him, and reshaping them in his own image with unparalleled brio and creativity. In this period Bowie was the ultimate chameleon, famously changing his image at breakneck speed—a true fashion icon fully grappling with his next challenge just as the public was coming to terms with his last phase. He was way ahead of the curve in understanding the volatile, variable nature of pop culture. His music changed shape and complexion just as rapidly and vigorously, and without the musical shifts his image transformations wouldn't have had nearly the same impact. As he told a reporter for Melody Maker in 1977, “generally my policy has been that as soon as a system or process works, it's out of date. I move on to another area.”

His work bears out that ethos. After several years in which he struggled to find an identity, he struck gold as the 1960s ended with his song “Space Oddity,” a chilling portent of modern alienation inspired by Stanley Kubrick's 2001: A Space Odyssey

Video

About

Bowie had already established this pattern of quickly moving on, and as Hunky Dory hit record store shelves he was already perfecting his alter ego Ziggy Stardust: the flamboyant, sexually ambiguous, and excessive glam-rock icon. Enlisting the talents of designer Freddie Buretti who crafted wildly colorful, form-fitting quilted uniforms, Bowie and his crack band the Spiders From Mars morphed into alien androgynies, with Bowie's shaggy blonde mop transforming into an angular, bright orange spiked cut. Adapting the vibrato-heavy croon of British actor and singer Anthony Newly, he reached toward fizzy feminine highs over the metallic rock 'n' roll riffery of guitarist Mick Ronson, all of the performances injected with a supreme sense of drama and artifice. On the cover of 1973's Aladdin Sane, he had morphed fully into an alien, with the iconic lightning bolt makeup bisecting his face and a globule of some otherworldly liquid pooling in one of his shoulder blades. As songs like “Starman,” “Sufragette City,” and “The Jean Genie” helped propel Bowie to stardom, he dismantled the Ziggy persona and his band, announcing his retirement from live performance. In the meantime he produced classic albums by some of his American heroes—Lou Reed and Iggy Pop and the Stooges—and watched one of his songs, “All the Young Dudes,” become a major hit by Mott the Hoople.

Following a palate-cleansing covers album in 1973, Pin-Ups, he made Diamond Dogs, a concept album based on George Orwell's 1984 with an all-new band—the hyperactive glam sound was transformed into something more restrained but equally hard rocking, producing indelible hits like the title track and “Rebel Rebel.” In the middle of touring the record in the US he embarked on his next transition, fully embracing American R&B, entering Philadelphia's iconic Sigma Sound with yet another group of musicians, including guitarist Carlos Alomar, a former James Brown sideman, and future soul legend Luther Vandross as a back-up singer. On the cover of 1975's Young Americans, his image had fully transformed into a suave crooner in high-waisted pants and double-breasted coats, his shock of orange hair now slicked back and blonde. Opening with the slinky, saxophone-soaked title track and closing with “Fame,” Bowie's first number one hit in the US, the singer had affected his most radical change yet. He carried on with that so-called “plastic soul” sound on Station to Station the following year, but his most adventurous and fertile period arrived next, when he moved to Berlin, and repurposed the sounds of Krautrock groups like Neu! and Kraftwerk and experimented with the cut-up technique of William Burroughs, producing three bona fide classics: Low, “Heroes”, and Lodger. With the help of producer Brian Eno, inventive sound processing warped the feel of the drums and turned electric guitars and keyboards into fluid textures and swirls of color, but ever the master syncretist, Bowie guaranteed gripping results no matter how outward-bound the process.

Video

About

He returned to New York to make Scary Monsters, his final masterpiece of the decade, where he fully embraced the nascent form of music videos, demonstrated by his memorable clip for “Ashes to Ashes.” He soon retreated from the public eye, emerging three years later in 1983 with Let’s Dance, the funked-up record that asserted his ongoing dominance for another decade. Over the next twenty years Bowie continued to change, absorbing ideas from reggae, electronica, and more, always plugged into evolving sounds around him, and while his image grew less chameleonic than it was during the 1970s, fashion and image remained crucial to his work, part and parcel, just as his engagement with acting on stage {bio: (Elephant Man [1980]) and screen (The Man Who Fell to Earth [1976], Merry Christmas Mr. Lawrence [1983]). Tastes and trends have never moved faster than today—Bowie anticipated this rapid cultural cycling—but his transformations were never hollow or glib, and that rigor rings truer and more meaningful than ever.

*This post first appeared in MCA Chicago (Fall 2014)}.