4 Things

Mika Horibuchi participates in our 4 Things series by sharing four things that influence her art and practice. See her work in the current Chicago Works exhibition, on view through Dec 2.

Photographs from my Grandmother

At 83 years old, my grandmother Sayoko Yokoyama had never picked up a brush with the intention of creating a picture, but she sought to learn how to paint. I sent her a set of watercolors after she expressed her interest. Shortly after, she returned an envelope in the mail containing photographs of her newly made watercolor paintings.

The subjects of her watercolors are landscapes, still lives, flowers—themes that teach us how to look in new ways through the practice of creating a picture. They speak a familiar language, one that is recognizable as a beginner’s exploration into learning how to paint. Some of the photographed watercolor paintings are painted from life, some mimic other paintings sourced from calendars or postcards, and some are studies of her teacher’s own paintings. As the moment that was captured in the initial form shifts into a different realm of light and time, what was meant to mimic becomes mimicked.

Zeuxis and Parrhasius

Juno and her handmaidens seated before the painter Zeuxis, and Parrhasius rushing to unveil his painting before a group of observers. Engraving by J.J. von Sandrart after J. von Sandrart.

Photo: Wikimedia Commons, Wellcome ImagesIn the fifth century BC, two painters in Greece were considered to be equals, rivaling each other in their fame and skill. Zeuxis and Parrhasius were both at the pinnacle of their abilities. A painting duel was held between the two greats in order to determine who was the more masterful artist. A crowd gathered to observe the spectacle of the competition, and the jurors assembled to view the two newly painted masterpieces that hung hidden behind a curtain.

Zeuxis was the first to be called upon to reveal his work. He pulled aside the curtain in one swift motion to reveal a bowl of fruit rendered so realistically that a bird flew past the enthralled audience, hurtling into the painted fruit. Lured by the grapes, the bird fell, a victim of the illusion. The crowd gasped and Zeuxis exuded glory, sure of his victory.

Zeuxis turned to Parrhasius and demanded that the curtain be drawn aside so that the competitor's painting could be seen. Parrhasius declined to do so. As the beguiled crowd gathered around him, reality began to, at last, slowly unveil. The curtain was not hiding anything but instead revealing itself. The curtain was the painting.

Curtains

Curtains have traditionally served multiple functions and fulfilled a variety of roles within the history of painting. They have been used to protect the surfaces of paintings from light and dust and other environmental irritants. They also serve a theatrical role of dramatizing the object of the painting; the curtain can be a device that creates a view through the act of moving the curtain in front of or pulling the curtain aside, concealing and revealing.

And when an image of a curtain is depicted within the parameters of a frame, the painting becomes a barrier that denies the viewer a view of itself, even as it becomes the picture itself. A curtain is not necessarily supposed to be looked at: rather, when placed in front of us, our natural response is to look through it. We are inclined to ask what lies beyond the curtain.

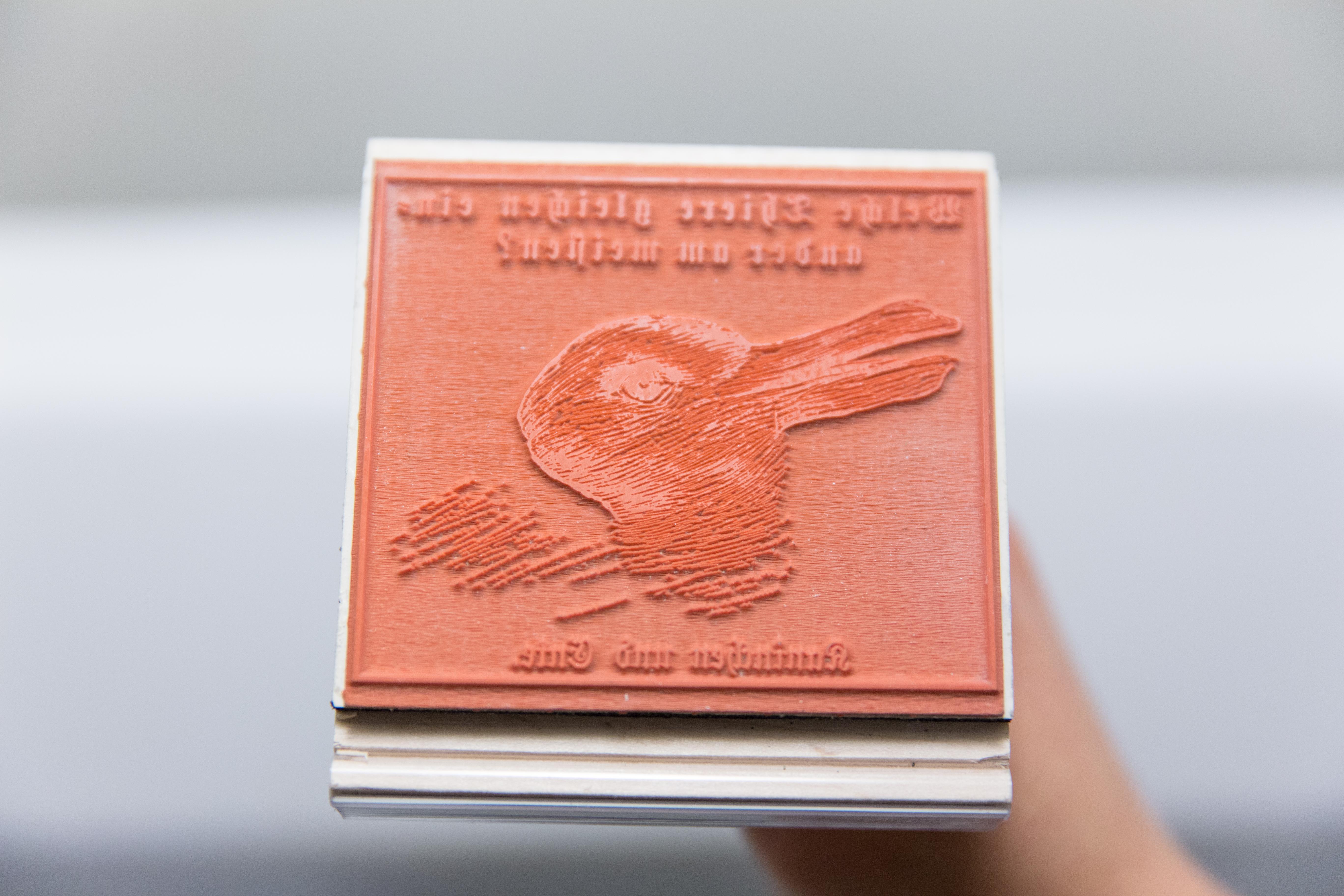

Stamps

A rubber stamp is an illustrative tool that promises to deliver a consistent and uniform mark. It is tricky to look directly at the face of a rubber stamp. In looking at a stamp, my natural instinct is to look to find the illustration that is fixed within the impression and relief of the stamp’s material. I may find myself looking not at the surface of the material object, but rather searching for the image that it promises to depict. Un-inked, the image that is expected of the tool is not yet drawn. As an object, it is a proxy and a stand-in. It suspends an idea beyond its material surface and the image is fulfilled cognitively. The image can be elusive.

Like the duck-rabbit illusion, when shifting from seeing the stamp to seeing the stamp as its intended mark, a cognitive switch happens while the physical object remains unchanged. The perception of the object fluctuates back and forth uncertainly between object and image, the thing itself and the thing that it represents.