4 Things

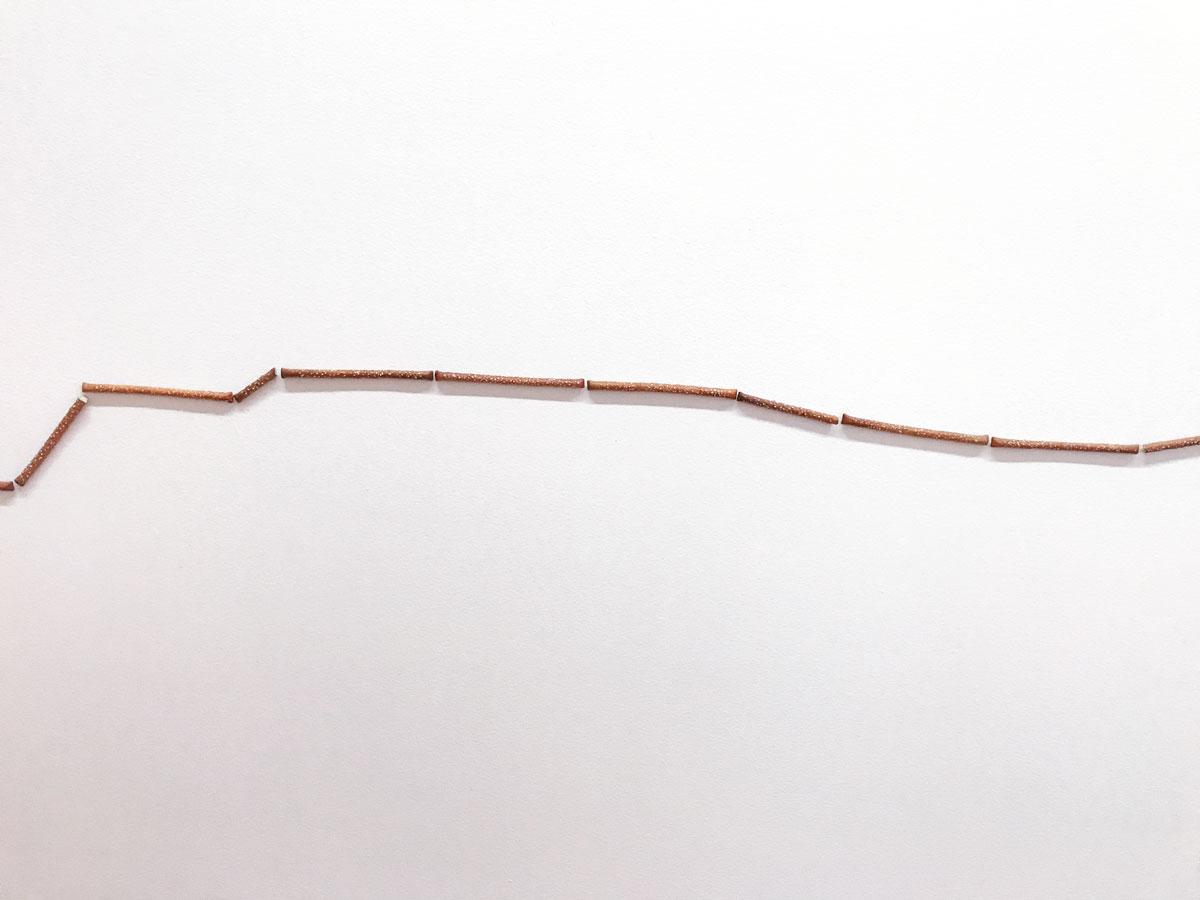

Chris Bradley, Horizon (detail), 2017. Cast bronze, paint, and hardware; dimensions variable

Photo © MCA ChicagoAbout

Chris Bradley participates in our 4 Things series by sharing four things that influence his art and practice. See his work in the current Chicago Works exhibition, on view through July 2.

About

I once spent a few weeks studying abroad in Ireland. While attempting to contextualize the stories of my Irish-American grandfather, I made art in and about the unique geographical area called the Burren. One project I explored on this trip involved carrying a potato to different sites, tossing it into the air as high as I could, and then quickly snapping a photo of the flying potato amid the Irish countryside. Despite its ridiculous nature, this potato-tossing act yielded interesting results. In some of the better photos, the potato is believably a massive flying object, floating across the distant landscape by its own will. I returned to the States with a refreshing perspective on the potential of something as basic as a potato. Soon after, I went on to make the first iteration of the moving potato sculpture that is in my Chicago Works exhibition.

About

Two friends and I traveled north from New Jersey to spend a long weekend on a thawing lake in the Adirondack region of New York. Upon our arrival, the ice on the lake had begun to recede from its shoreline, revealing a thin ribbon of water that separated us on shore from this freshwater berg. The seasons were in flux, and the weather was kind. There was sun, then steam, and the ribbon began to grow. Soon, the ribbon was wide enough for a rowboat. We clumsily propelled ourselves between ice and shore. A cooler of food and refreshments bobbed in tow. We rowed in circles for three days. In this time, the ribbon became lake, and the berg reduced to a cube. We witnessed the lake come alive for another year. It was spring.

About

From age one to six, I lived in a suburb in northern New Jersey that was well known for its small, manmade lakes. There, my family spent a lot of time swimming, fishing, and, my favorite, searching for turtles. We’d see turtles while canoeing around the lakes, but I never successfully caught one despite being outfitted with various nets that I had engineered specifically for this event. One day, my prayers were answered, and a turtle came to us. We found it crawling up the walkway toward our front door. I picked it up and it peed on me. Quickly the kiddy pool became its new home. We fed it anything and everything, even ground beef. It was more than a pet. He was our guest. Eventually, it became clear that we needed to bring him back to one of the lakes. Setting him loose was a sad, but worthwhile lesson. A few days later, our doorbell rang. It was our neighbor asking if we had seen the exotic turtle that he had recently purchased for his backyard pond. We said, “No.”

In 2011, I purchased a red-eared slider from Chicago’s Chinatown neighborhood. This breed is the most commonly sold turtle in America, and in turn is considered invasive due to their frequent release into the wild. (I haven’t any such plan.) I named him Fangs. Later that year, Fangs made an appearance in my solo exhibition at Shane Campbell Gallery as the occupant of a large fountain sculpture that represented an artificial oasis with palm trees made of painted cast bronze pretzel rods. He and I have been best friends ever since.

About

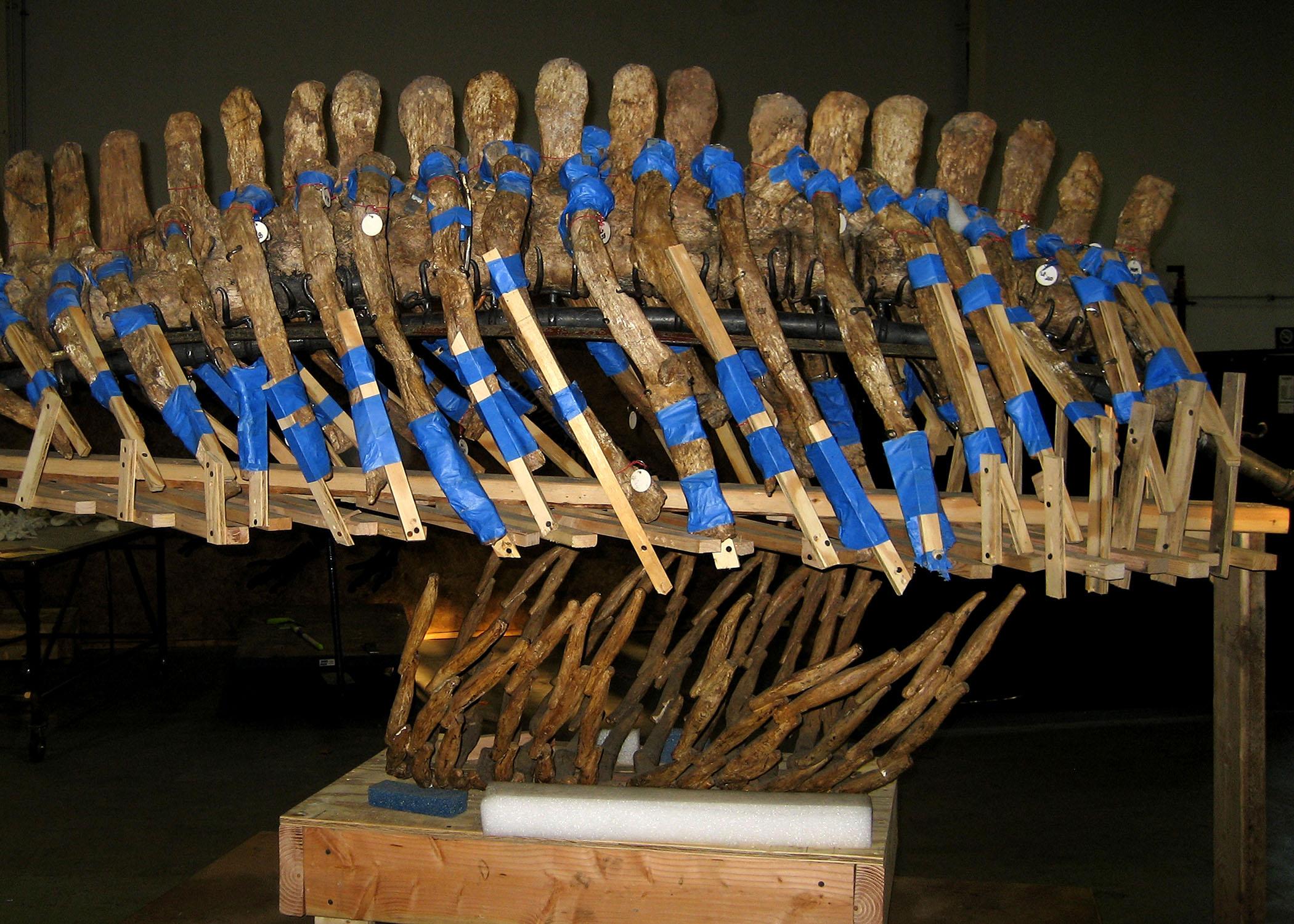

My first job as a postgraduate was with a company in New Jersey that specialized in preparing dinosaur displays for museums—the same company that prepared the great Tyrannosaurus rex named Sue at the Field Museum. I started in fossil restoration and moved on to mount making, which involves forming steel to safely cradle and accurately position the skeletal elements. Paleontologists would occasionally visit the warehouse to advise on our progress. Each part of the skeleton required a slight variation in mount making to accommodate its specific anatomy. Ribs were especially difficult given the fragile nature of what is essentially a long, slender, and heavy rock. During one hot summer, we spent weeks mounting the ribs of a Diplodocus. To survive the heat and the tedious task at hand, my colleagues and I jovially yelled “Riiiibs!” in high-pitch voices across the warehouse floor.

A couple of years later I moved to Chicago. Craigslist gave me two roommates. We each had something to offer. Roommate 1 had a hamster that suffered from scrotal elephantiasis. Roommate 2 was a party-throwing virtuoso. I had a car so I was the driver. On a hot summer night, with the windows down, the three of us drove to the grocery store. On the way, I told them about dinosaurs, mount making, the heat, and ribs. At a red light, in the climax of the story, I yelled in the same high-pitch voice as I had done in that warehouse, “Riiiibs!” We laughed. I yelled it again. Then, from the car to our left, a woman angrily yelled, “What did you say?” She immediately followed up this question by throwing part of her takeout dinner at us. It was a chicken wing.