Uncovering the MCA’s History: A 16mm Film Preservation

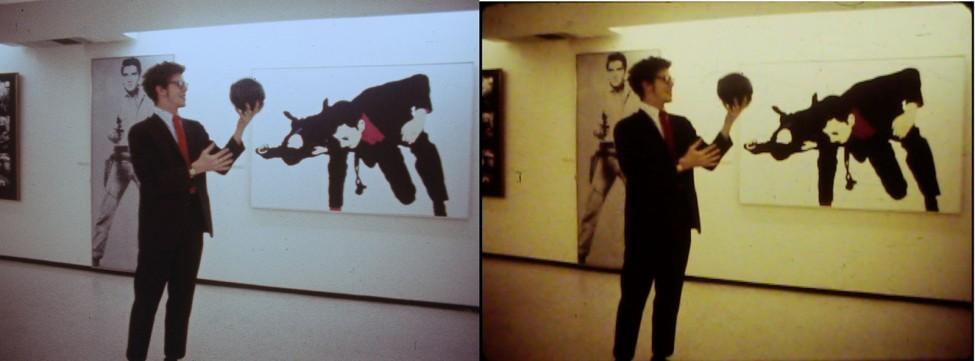

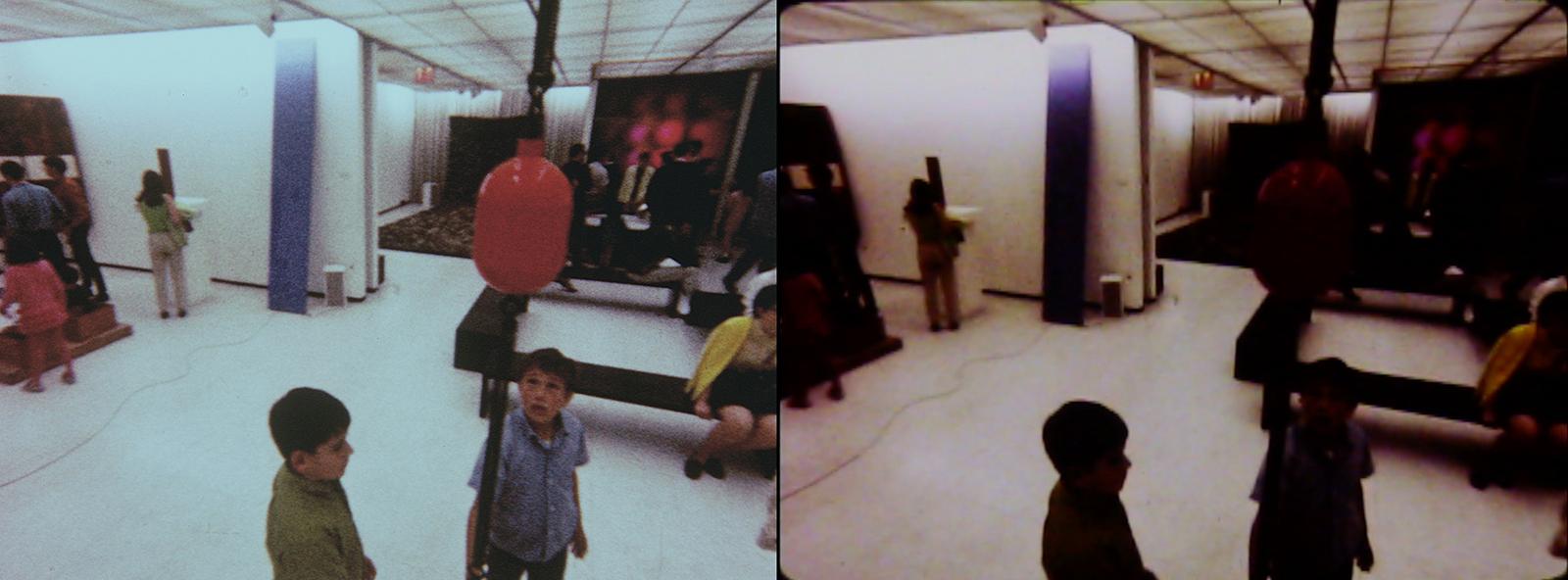

Comparative frame grab from David Katzive's 16mm film

All photos © MCA ChicagoAbout

With the conclusion of [](http://www2.archivists.org/initiatives/american-archives-month/american-archives-month-2014) National Archives Month at the end of October, Curatorial Fellow Michelle Puetz shares the details of a conservation project that she has been working on for some time with a number of insights into conservation practice for archivists, librarians, and conservators.

on the MCA’s exhibition history project

When I began my Andrew W. Mellon Postdoctoral Curatorial Fellowship in February 2012, one of the first projects I proposed emerged directly from the work that the MCA’s Library and Archives staff had been doing to organize, archive, and digitize materials related to the museum’s exhibition history. The project I’ve been working on is collaborative at its core, and illustrates the close connection between curatorial work and the various archival projects taking place in the MCA Library and Archives.

Currently unnamed (I refer to it as plainly the “MCA Exhibition History Project”), this collaborative effort will make the MCA’s exhibition history prior to 2000 available in a dynamic format on the museum’s website. In anticipation of the museum’s 50th anniversary in 2017, I’ve been working closely with the Library and Archives staff, as well as a couple of curatorial interns, to compile a comprehensive list of the museum’s exhibitions, write exhibition descriptions, and locate photographic documentation in the museum’s archives.

For a historian and researcher like myself, the museum’s exhibition files and ephemeral material are a real treasure trove. There are few things more exciting than working with primary materials and original documents, and the MCA’s exhibition records often contain notes and correspondence that complicate the more straightforward narratives published in exhibition catalogues.

When I was working on my PhD, I spent a lot of time doing primary research at a variety of film and museum archives including MoMA, the Burchfield Penney Art Center in Buffalo, and Anthology Film Archives in New York. I was always thrilled to locate audio or moving image documentation of the artists I was writing about. Hearing an artist speak about their work to an audience, answer questions during an informal chat with curators, or introduce a screening all provide invaluable insights into their work, influences, and thinking at the time of the recording. I was incredibly excited to discover that the MCA has a long history of interviewing exhibiting artists, and that many of these tapes have survived and are now housed in the archive.

Video

About

Because I have a background in film archiving and preservation, one of my concurrent and connected projects has been to gradually start digitizing these artist interviews, most of which were mastered onto ¾” Umatic tape, a videotape stock that is rapidly deteriorating. The interviews—with artists including Nam June Paik, Sol LeWitt, Magdalena Abakanowicz, Jeff Koons, Alice Aycock, and Max Neuhaus, among many others—are fascinating portraits and documents of the MCA's early exhibitions. When the project is completed, these digitized interviews will be made available to researchers and integrated into the MCA's online exhibition history. Check back for future blog posts containing excerpts from some of these video interviews!

With the hope of locating more documentation of the museum's early history, the Library and Archives staff and I made a few trips to the MCA Warehouse last spring. (For more information on the visits and discoveries made there, read page 13 of the MCA Magazine online PDF.) We were specifically looking for two cases of audio cassette tapes that contained artist interviews and recordings from performances and lectures in the 1970s and 1980s, as well as 16mm film footage that we heard included documentation of the MCA's earliest exhibitions. We were incredibly excited to find both the audio cassettes and the 16mm film, and quickly started the process of inventorying the collections and preparing them for digitization.

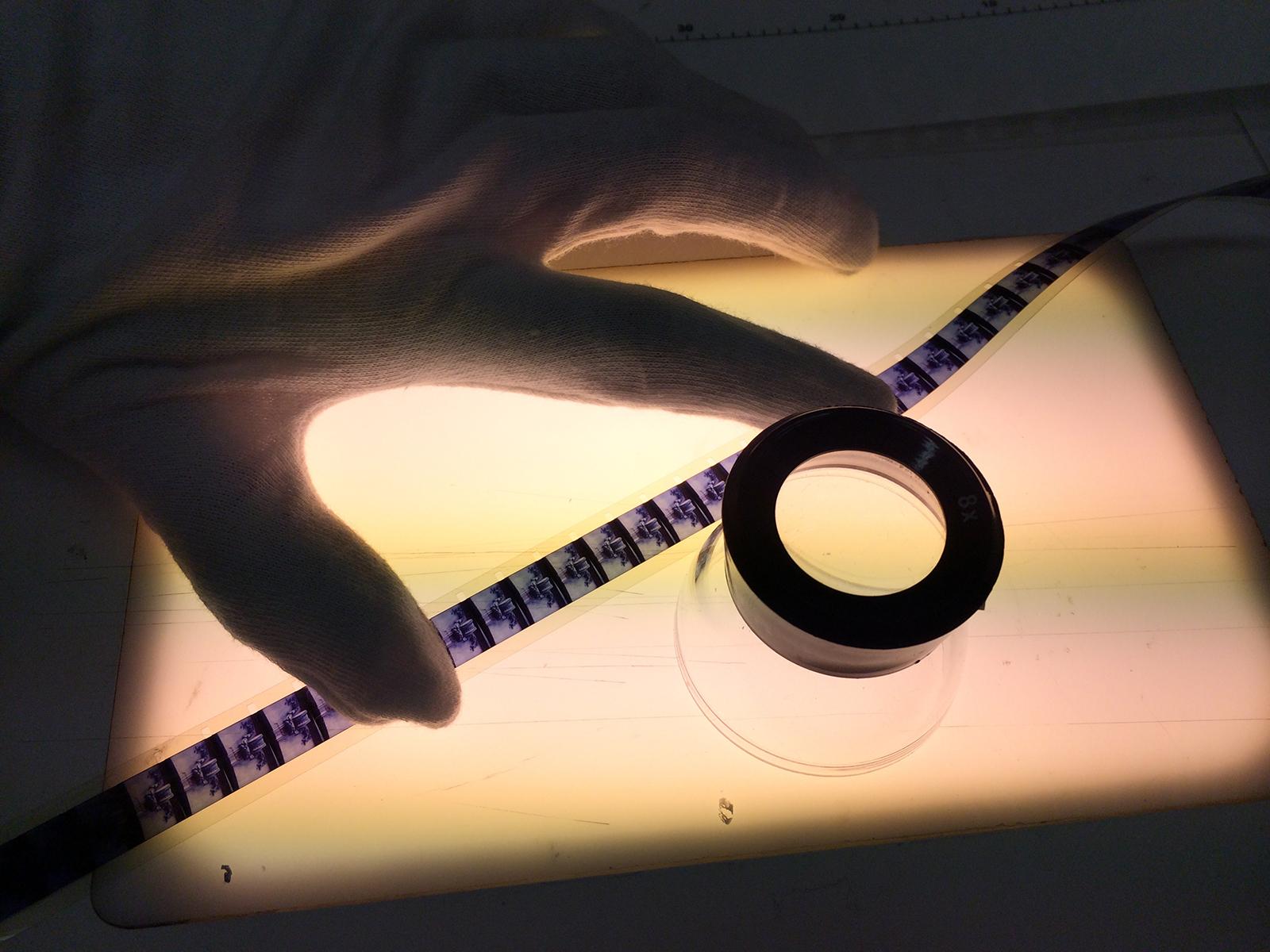

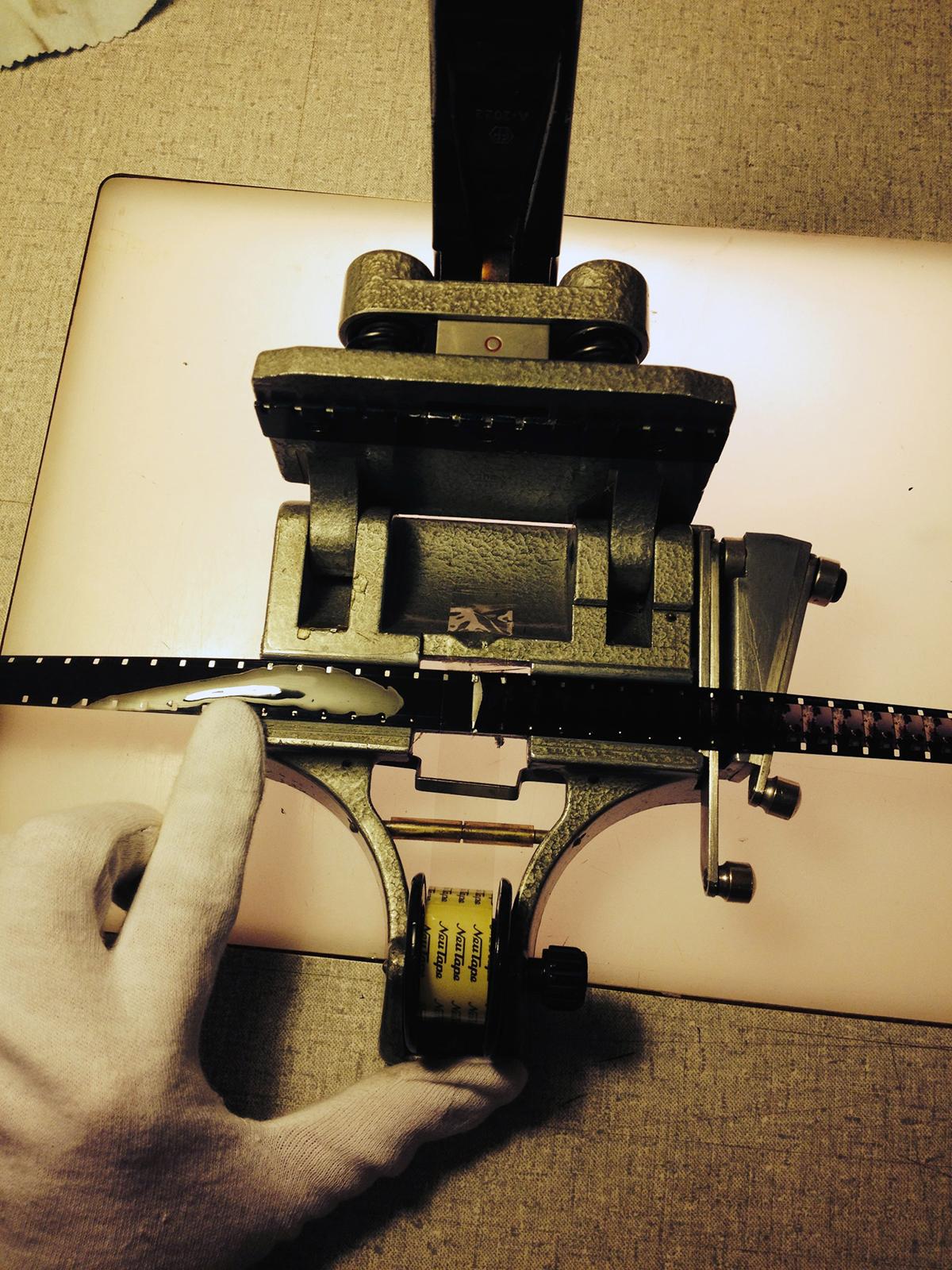

The weekend following our discovery, I spent a day inspecting and making very minor repairs to the film reel, which was covered in dirt and dust.

The film was on a rusty 16mm metal reel that had not been stored inside a can, so it required a lot of gentle surface cleaning and careful handling

Because the film was loosely wound around the reel, it was torn and damaged in a few spots

About

It was clear that the reel was a composite of many films spliced together—some of the footage included title sequences and soundtracks, some appeared to be documentation of exhibitions both in the installation process and on view, and others were creative responses to the exhibitions {bio: (one really remarkable example of this is a single-frame animation sequence created using the individual panels of Warhol's famous Flowers piece [1964]).

Mary Richardson, the MCA's Library Director, and I were able to determine that David H. Katzive, the museum's first curator, shot almost all of the footage on the composite reel. Katzive was not only a talented curator, but a very astute filmmaker. Some of the footage was fairly straightforward documentation of early exhibitions (dating from 1967–1970)}, but the reel also contained two complete films that Katzive made and distributed through Chicago's Center Cinema Coop: Christo–Wrap In–Wrap Out, which documents Christo's legendary 1969 wrapping of the MCA, and Concrete Traffic by Wolf Vostell, which captures the process of creating Vostell's concrete sculpture in 1970. The reel also includes a short film made by Jerry Aronson and Howard Sturges that documents the participatory art exhibition Options, which was on view in the fall of 1968. In addition to these completed films, the reel contains documentation of the museum's earliest exhibitions including 1967's Pictures to Read/Poetry to be Seen 1968's Made with Paper, George Segal: Twelve Human Situations, Robert Whitman: Four Cinema Pieces, and Tom Wesselman: The Great American Nude 1969's Art by Telephone and 1970's Andy Warhol Retrospective.

Our archiving and preservation of the film consisted of multiple stages, and has taken eight months to complete. First, I inspected the film on a rewind bench to identify the content as best as possible.

After this initial work was completed, we had a quick telecine made of the entire reel, which allowed us to see a low-quality transfer of the film. I can't even begin to explain how excited I was to see everything that the reel, almost an hour in length, contained. Because I spent years working at the Chicago Film Archives with unique 16mm film material, specifically amateur and home movies, I knew that the film reel was not only irreplaceable {bio: (it is the only extant copy), but that it was essential to quickly make plans to preserve both the original film and make access copies available to researchers.

It was clear that the reel was a composite of many films spliced together—some of the footage included title sequences and soundtracks, some appeared to be documentation of exhibitions both in the installation process and on view, and others were creative responses to the exhibitions (one really remarkable example of this is a single-frame animation sequence created using the individual panels of Warhol's famous Flowers piece [1964]).

Mary Richardson, the MCA's Library Director, and I were able to determine that David H. Katzive, the museum's first curator, shot almost all of the footage on the composite reel. Katzive was not only a talented curator, but a very astute filmmaker. Some of the footage was fairly straightforward documentation of early exhibitions (dating from 1967–1970)}, but the reel also contained two complete films that Katzive made and distributed through Chicago's Center Cinema Coop: Christo–Wrap In–Wrap Out, which documents Christo's legendary 1969 wrapping of the MCA, and Concrete Traffic by Wolf Vostell, which captures the process of creating Vostell's concrete sculpture in 1970. The reel also includes a short film made by Jerry Aronson and Howard Sturges that documents the participatory art exhibition Options, which was on view in the fall of 1968. In addition to these completed films, the reel contains documentation of the museum's earliest exhibitions including 1967's Pictures to Read/Poetry to be Seen 1968's Made with Paper, George Segal: Twelve Human Situations, Robert Whitman: Four Cinema Pieces, and Tom Wesselman: The Great American Nude 1969's Art by Telephone and 1970's Andy Warhol Retrospective.

Our archiving and preservation of the film consisted of multiple stages, and has taken eight months to complete. First, I inspected the film on a rewind bench to identify the content as best as possible.

About

This was followed by a gentle cleaning and minor repairs made to torn perforations and old splices.

After this initial work was completed, we had a quick telecine made of the entire reel, which allowed us to see a low-quality transfer of the film. I can't even begin to explain how excited I was to see everything that the reel, almost an hour in length, contained. Because I spent years working at the Chicago Film Archives with unique 16mm film material, specifically amateur and home movies, I knew that the film reel was not only irreplaceable (it is the only extant copy), but that it was essential to quickly make plans to preserve both the original film and make access copies available to researchers.

It was clear that we had found an incredibly valuable document of the MCA's early history, and I began to research the options available to us for archiving the unique and original 16mm (analog) print, preserving the original material and any copies (both archival master transfers and access files) that we might make, and the best quality preservation options currently available. Rapid changes are taking place in the world of film preservation—in particular, new options for extremely high-resolution digital scans of analog originals. After consulting with several film archivist colleagues, I determined that rather than pursue what, until just a few years ago, had been considered the best option for film preservation projects (which involved making an archival master copy on 16mm film, new 16mm intermediary and printing elements, a 16mm film access copy, and, finally, digital access copies), we would work with one of the premiere film preservation labs in the US, Colorlab, on a digital preservation of the 16mm original.

The preservation process Colorlab used for the digitization of the film entailed the rewash and cleaning of the original reel (which removed a great deal of surface dirt and dust), a flat transfer on a Spirit 2K film scanner (providing a pixel resolution of 2048 x 1536), and DaVinci color correction and image stabilization. It was very important to us that the digital preservation be a preservation (not a restoration, reconstruction, or re-creation) that would retain the quality and feel of the original material Katzive shot. In preservation, these kinds of decisions are ethical ones: How do you maintain the artist's original intent with the work? What do we base our preservation decisions on? With a material like film that was always intended to be duplicated and distributed, what constitutes the original?

While it was important for us to preserve the material as described above—with the intent of making the footage as accessible and available as possible—we also needed to archive the original 16mm reel. This meant rehousing the film in an archival can and on a film core (rather than a projection reel), and storing it flat and in a humidity- and climate-controlled environment.

The film in its new can—what a difference from the original dirty metal reel!

About

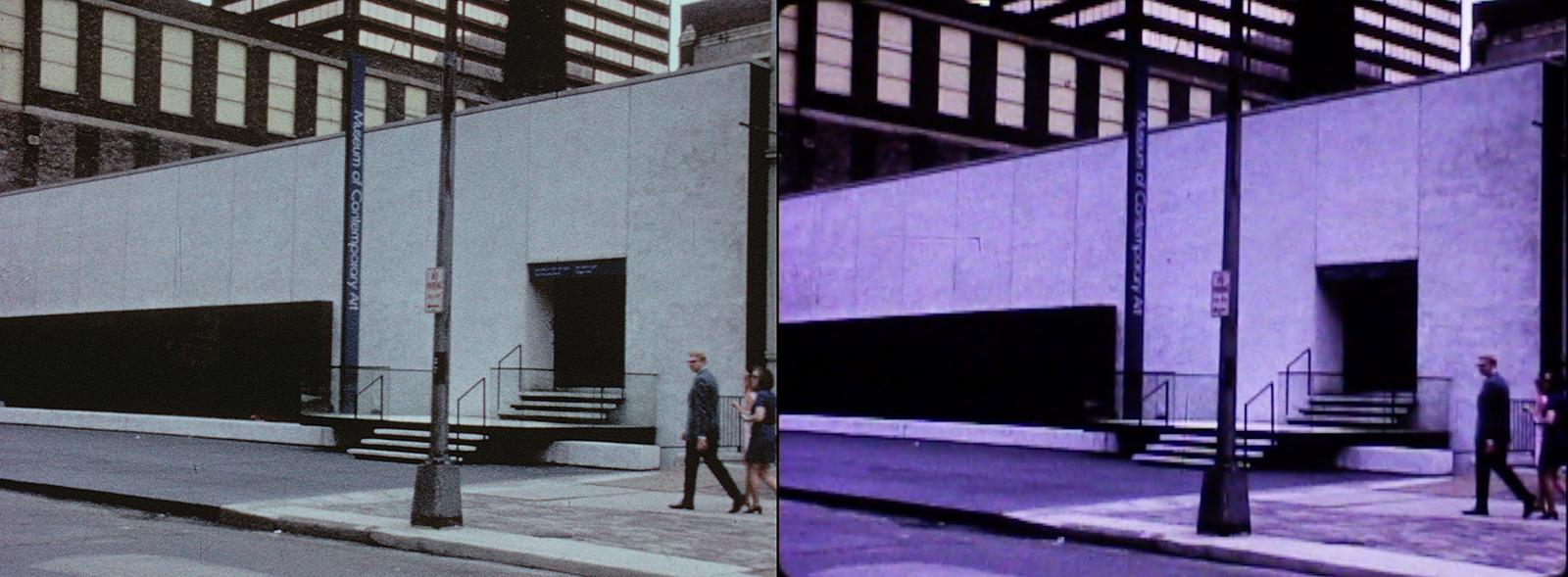

Following are a series of comparative stills that show one frame taken from the archival preservation scan on the left and the pre-preservation telecine transfer of the film on the right.

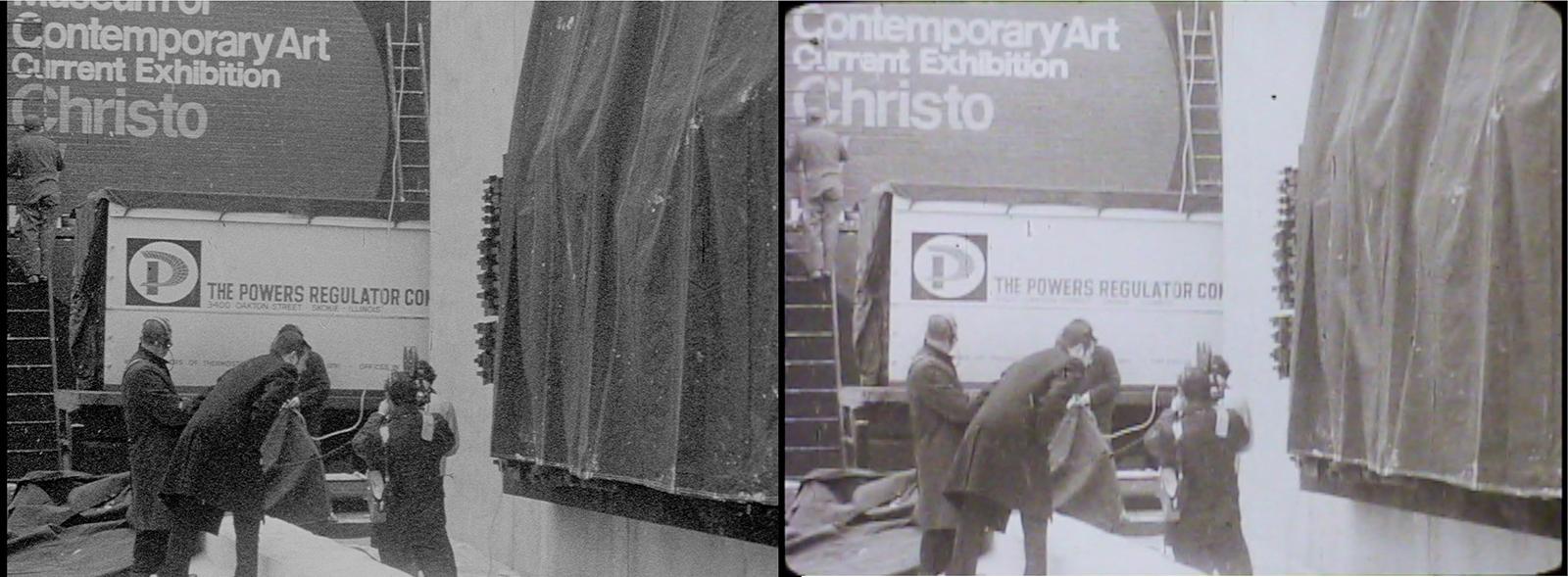

Comparative frame grabs from David Katzive's 16mm film

About

The difference in quality is immediately apparent. After preservation, the original film is much more legible in terms of the sharpness of the image (evident in the visibility of the film grain) and in our ability to recognize key aspects of the artworks shown.

Comparative frame grabs from David Katzive's 16mm film

About

I have also created videos that show both the archival preservation scan {bio: (on the right) and the pre-preservation telecine transfer of the film (on the left). Even though these files are being presented as compressed copies in this post, the difference in quality is remarkable.

The first video clip shows the two transfers of David Katzive's film Christo—Wrap In—Wrap Out (1969)}, which documents the artist's first building wrap in the United States.

Video

About

The second video clip shows two transfers of an excerpt taken from Jerry Aronson and Howard Sturges's film documenting the participatory art exhibition Options

Video

About

The final, silent excerpt contains footage of Claes Oldenberg's mural, Frayed Wires, painted in May 1969. One of three large-scale public art projects that the MCA commissioned Oldenburg to create between 1967 and 1972, the mural was painted on a wall adjacent to the MCA's former location at 237 East Ontario Street. The painting was carried out by a local business, the Arrow Sign Company, which was hired to paint all three of Oldenburg's MCA mural pieces. At the beginning of the video, you can see two men on a scaffolding painting white primer over Oldenburg's first mural project, Pop Tart

Video

About

All photos and comparisons by Michelle Puetz