Chicago Comics: 1960s to Now Exhibition Tour

Video

Join guest curator Dan Nadel on a tour of the exhibition Chicago Comics: 1960s to Now. The exhibition features more than 40 artists including Charles Johnson, Jay Lynch, Lynda Barry, Chris Ware, Kerry James Marshall, and many more.

Transcript

[MUSIC PLAYING]

DAN NADEL: Hi. I’m Dan Nadel, curator of the exhibition Chicago Comics: 1960s to Now at the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago. The exhibition celebrates the city’s legacy as home to some of the most important cartoonists of the past century, forty of which are featured in the show. Today I’ll take you through the exhibition while talking about the different movements, cartoonists, and aspects of the great tradition of Chicago cartooning.

What made Chicago into a hub for comics? Many factors played into the growth of the city’s cartooning culture, including the fact that it was a major hub for the nation’s color printing industry in the early twentieth century. For decades, Chicago produced some of the most popular comic sections in the country. You can see a few iconic strips here, including Chester Gould’s Dick Tracy and Dale Messick’s Brenda Starr, both of which were published by the Chicago Tribune, and continued well into the sixties and seventies.

Like the city itself, the industry was clearly divided between Black and white newspaper publishers. The Chicago Defender and The Pittsburgh Courier published Black Chicago cartoonists like Jackie Ormes and Jay Jackson, both of whom imbued their work with racial critique in 1940s and fities America. Through their focus on the daily experience of being Black in Chicago, these artists laid the formal and thematic foundations for the often-radical work of the cartoonists who would follow them.

Before he wrote Middle Passage, Charles Johnson was an aspiring cartoonist. He produced a remarkable book of cartoons about the Black experience in America— Black Humor, published by the Johnson Publishing Company, who also published Jet, Negro Digest, Ebony, and other magazines and books.

Cartoon— It’s Life As I See It— encapsulates the humor, the biting edge, and the wisdom of Johnson’s cartoons. It’s also the title of the accompanying book for the show. Johnson was kind enough to loan numerous cartoons for this exhibition, some from the early 1970s. Here, the satires on both the Black Power movement and the Black experience in Chicago remain as relevant now as they were then. Over here, Johnson decided to redraw numerous cartoons from Black Humor for the purposes of exhibiting these works.

There are lots of details in this show. One very important detail is right here. Jay Jackson was one of the great Chicago cartoonists of the twentieth century— also, interestingly, did a lot of advertising work for Valmor and Lucky Brown’s hair products. These were products aimed at the Black population and advertised on the same page that his comics would appear.

So in a case like this— "Lucky Brown hair dressing: go to town with Lucky Brown"— the ways in which hair was depicted in these packages was later adapted by some of the great Chicago artists of the sixties and seventies— Christina Ramberg, for example, Karl Wirsum, Jim Nutt, Roger Brown. All of these artists avidly collected these packages, and adapted the way in which the hair sheen was drawn into their work and into their ideas about how hair, and the body, and the face could be presented. So just by thinking about Jay Jackson and the work he did for an advertisement on the same page of his comic, you can trace a history of twentieth-century rendering, drawing, design right in this object.

By the 1960s and seventies, the city had evolved into the epicenter for an art form that was rapidly expanding beyond the pages of newspapers and being reshaped by the radical politics of the era. The sixties saw the rise of the underground press in Chicago. Papers like The Seed and comic books like Bijou Funnies began to popularize the transgressive work of names that are now legendary in comics: Jay Lynch, Skip Williamson, Grass Green, Robert Crumb, and Daniel Klein.

These artists made comics that addressed everything from race and class to drugs, sex, rock and roll, mysticism, and anarchy. All of these artists were pushing comics into radical new territory, building a creative community that still flourishes in Chicago today. By the late 1960s, comics for adults were so popular that they could take on all kinds of topics. Tom Floyd, an illustrator, designer, and cartoonist at Inland Steel, chronicled his entrance into the white-collar workforce as the sole Black man at the company in a pioneering graphic novel called Integration is a Bitch.

Jay Lynch, who lived in Chicago for decades, was seen by many as the great connector of the underground. Lynch produced a wonderful comic strip called Nard n’ Pat. He was the editor and publisher of the fantastic underground anthology Bijou Funnies. He also lectured at the Art Institute about the history of comics in the early 1970s. Lynch was really the hub in the Midwest for underground comics.

Nard n’ Pat is a great example of this. In this strip, Nard and Pat get tired of the way Lynch is drawing them, so they suggest that perhaps other underground cartoonists could draw them instead. And so Lynch brought in all of his friends. The royalty of underground comics at the time all contributed their version of how Nard and Pat might look if another cartoonist was employed to render them.

The underground comics culture of the 1960s and seventies, along with cheap rent in many schools and universities, drew tons of young cartoonists to Chicago. By the 1980s and ‘90s, comic strips, and alternative weeklies, and comic books published by independent houses became venues for all manner of personal expression. Young cartoonists, like Lynda Barry, Dan Clowes, Chris Ware, Gary Leib, and many, many others gathered in Chicago to pioneer new forms of comics, telling surreal, empathetic, personal, funny, and highly sophisticated stories in their comics.

This recent work by Dan Clowes is a great example of how comics were made. In this comic, Dan actually explains each of the production techniques that he moved through as a cartoonist starting out in the early 1980s. So for example, he talks about rubylith, cutting a screen to achieve a color. He also talks about zipatone, an adhesive applied to the comics page to get tone. He also talked about the move to digital so that comics became drawn in black ink and blue pencil, and then the color was filled in in Photoshop. All of these production techniques are woven into one narrative here on this page.

Nicole Hollander is one of the great cartoonists to come out of Chicago. Her syndicated strip Sylvia ran nationally from 1980 until 2012. She started out working for The Spokeswoman, a feminist magazine in the 1970s. Here we see her iconic character Sylvia just having a beer asking, where’s the man can ease the pain like a satin an gown— a wonderful quote from Dorothy Parker that epitomizes Sylvia’s tough, funny, ironic, hard-living self. Throughout, we see Sylvia, as usual, with her beloved cats, her beloved booze, coffee, her hated Ronald Reagan, and innumerable, uncountable doofuses. But there she is, Sylvia.

Over the last two decades, comics have exploded, not only in Chicago, but around the globe. Cartoonists have embraced all subjects and formats, from graphic novels, to DIY zines, to Instagram stories. Their subject matter is just as diverse, focusing on identity, bodies, architecture, and history. Cartoonists have also made the welcome return to the political commentary of their forbearers, producing work that is sharp, critical, and urgent. Meanwhile, multiple generations of cartoonists continue to teach at the city’s many colleges and universities, bolstering its reputation as the educational center and heart of the medium.

Comics is a medium that really encourages worldbuilding. You see it in superheroes. You see it in the literary fiction of Chris Ware. You see it in this installation by Emil Ferris. Karen is a young cartoonist, illustrator, artist finding her way. Here we see her briefcase filled with samples of art, her sketchbook, her favorite stuffed animal, pens, and so much more. For Emil, the life of Karen, the life of My Favorite Thing is Monsters— one that needs to be experienced in the book, but can also be seen in three dimensions, in space, and brought to life in a different way entirely.

Ivan Brunetti grew up in Chicago. His comics began with a scathing autobiographical series called Schizo in the 1990s. He went on to draw numerous New Yorker covers. He’s edited lots of important anthologies about the history of comics. And his legacy is extended, because he has taught some of the great cartoonists of the twenty-first century. Here you can see things that Ivan makes for fun, and to also release some of the energy pent up in the drawing of comics. You can see three-dimensional versions of the way that he draws figures. Ivan is applying very simple shapes— circles, squares, triangles— to tell profound stories about the human condition.

Chris Ware is practically synonymous with Chicago comics. For this exhibition, Chris designed his own installation. He worked closely with the architects, Norman Kelley, who designed the show— and Chris brought out things that he’s never shown before, sculptures that he made to personify the characters in his comics, new work meant to help elucidate the relationship between the page and three-dimensional space, and an entire comic strip shown as a whole: Joanne Cole from his graphic novel Rusty Brown.

Cartoonist Bianca Xunise caused quite a stir last year with her comic Mask, which we see blown up on the wall here. In her syndicated strip, Bianca just illustrated an actual event from her life. Bianca’s strip received numerous reader complaints from people who did not like the message. She stuck by it, her editor stuck by it, and we present it here as an homage to the spirit of perseverance inherent in comics and in her work.

Over here, Kerry James Marshall, the renowned painter, has been drawing comics for over 25 years. His graphic novel Rythm Mastr is excerpted here, with a section drawn especially for this exhibition. Kerry employs dioramas and models to draw from. And he makes his drawings on large sheets, which he then scans, letters digitally, and then prints and installation form like this, as a comic strip. Eventually, this strip and numerous others will make up the full graphic novel Rythm Mastr.

Though the exhibition is organized chronologically, as you move through time, you’ll find individual presentations by some of the master cartoonists of Chicago. You’ll see presentations on Lynda Barry, Nicole Hollander, Kerry James Marshall, Chris Ware, Emil Ferris, Edie Fake, and many, many others. All told, these cartoonists are bound by the desire to use the medium to express anything they desire.

The wonderful thing about the comics medium is that all that stands between you and a comic is a piece of paper and a pen. I encourage you to join me and visit this exhibition, which will be on view through October 3, 2021. Thanks so much for joining me.

Chicago Comics: 1960s to Now

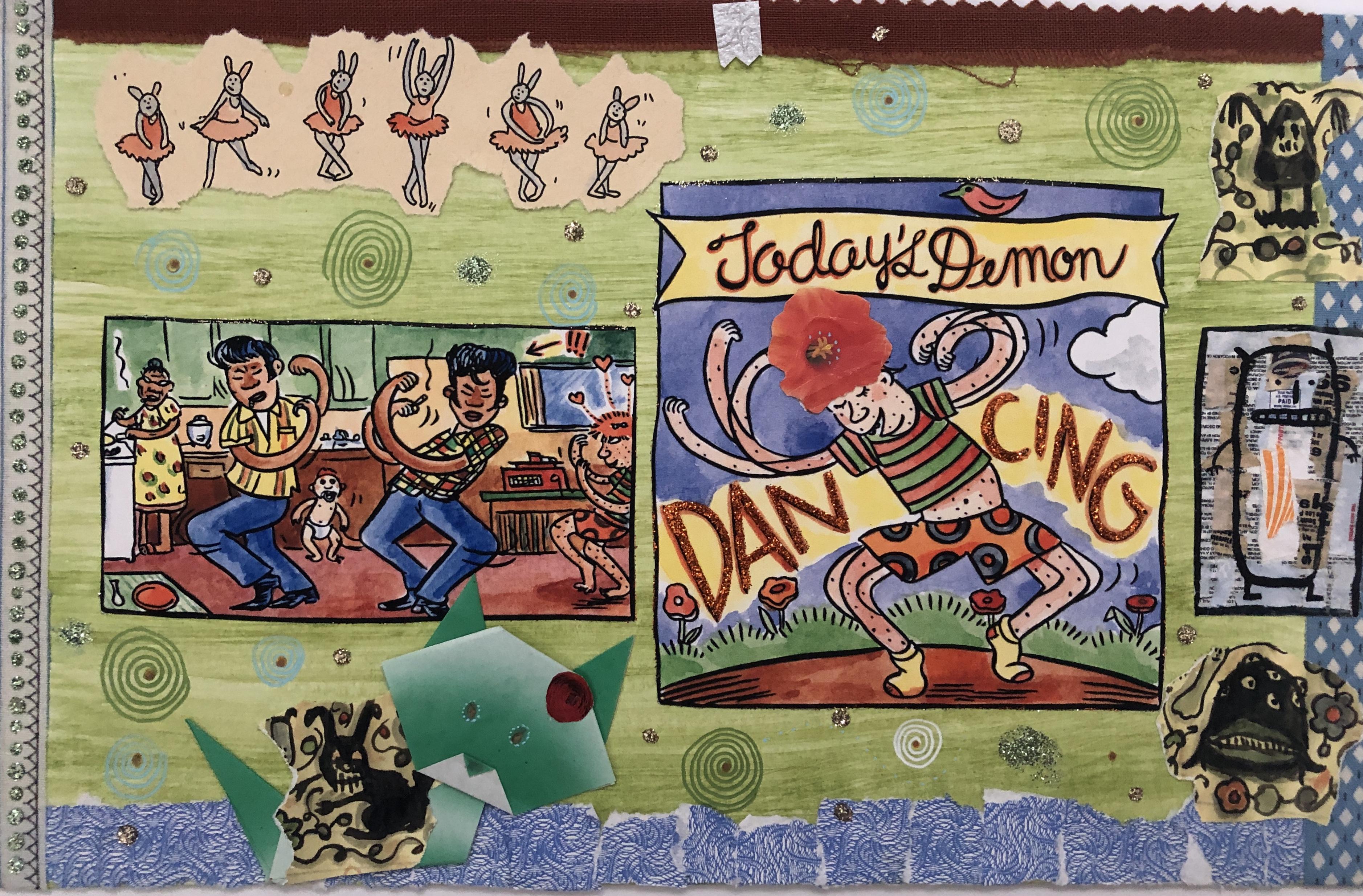

Lynda Barry, 100 Demons: Dancing, 2000–2002. Watercolor on board; 8 x 10 in.

Courtesy of Adam Baumgold Fine ArtChicago has been a center for comics for decades—a haven not only for making and publishing cartoons, but also for innovating on the medium. Chicago Comics: 1960s to Now tells the story of the art form in the influential city through the work of Chicago's many cartoonists: known, under-recognized, and up-and-coming.