The Community of Everybody and Nobody

Featured images

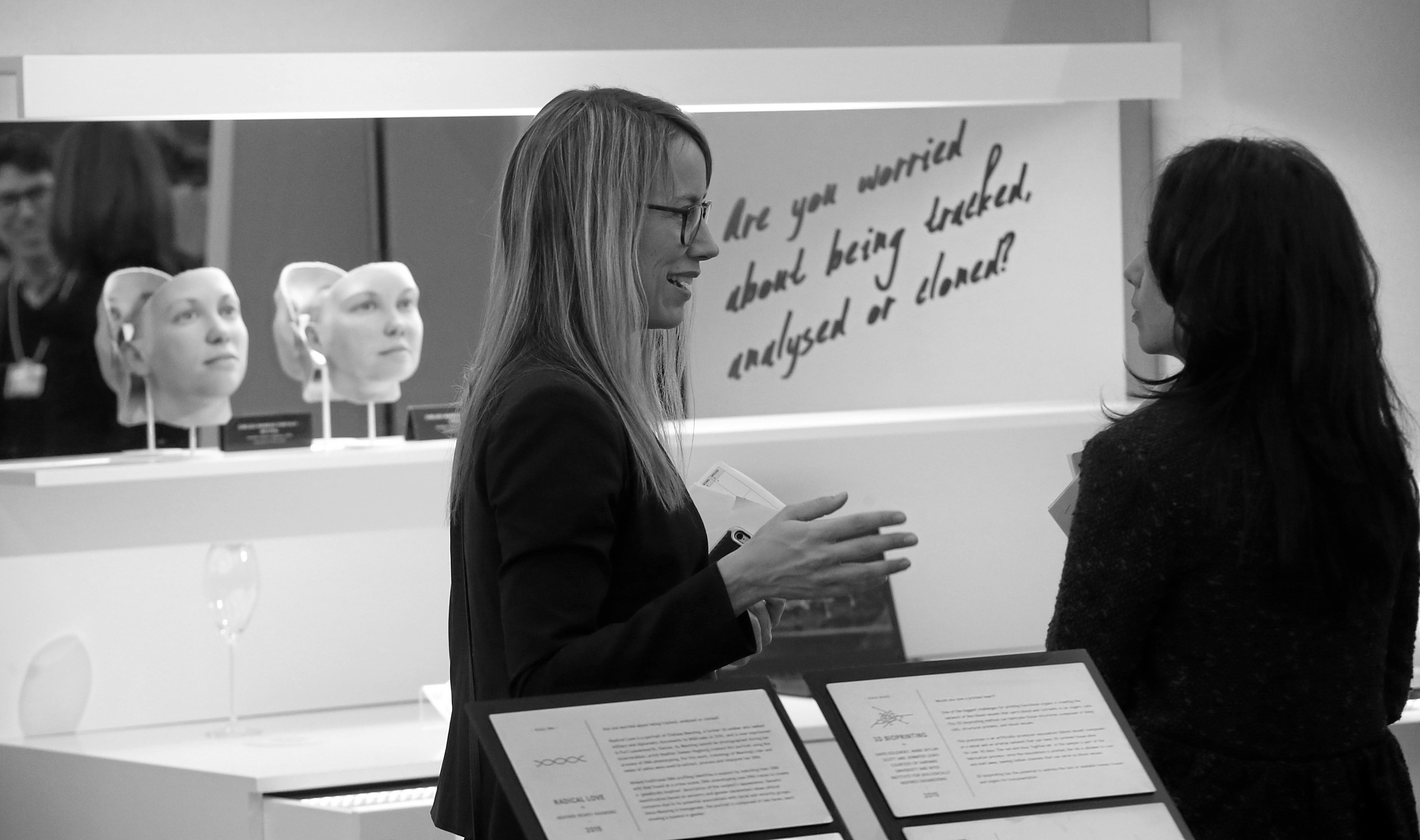

Installation view of Heather Dewey-Hagborg, Radical Love: Chelsea Manning, 2015. Biel Bienne Photography Festival, Switzerland, 2016

Intro Text

To accompany our I Was Raised on the Internet exhibition on view through the end of the summer, the MCA is publishing a print collection of writings from industry experts on various internet-related topics. With subject matter ranging from autonomous image interpretation to the presence of pets on the web, the I Was Raised on the Internet reader explores the complexities of internet culture—in the past, present, and future.

Joanne McNeil, one of the contributors to the upcoming publication, is a writer interested in the ways that technology is shaping art, politics, and society. For her piece, “The Community of Everybody and Nobody,” McNeil explores how “communities” manifest online on sites ranging from Wikipedia to Facebook.

This excerpt from the I Was Raised on the Internet reader, available for purchase this fall, provides a glimpse into one of the text's complex explorations of the ways the internet has changed our experience of the world.

It has become cliche to talk about how old “new media” really is. (“Card catalogs were the first search engines!” “The phone book was the first social network!”) This is because our behavior with new products is usually an awkward transition, picking up where habits with the last dominant form of media left off rather than approaching technology as a blank slate. But something truly unusual about our time—our lives after the internet—is how often people use “community” to refer to a collection of total strangers.

A community is a group of people organized by some uniting force, usually a common location or a shared hobby or identity. There are church communities, activist communities, communities of birdwatchers, and communities of professionals who get together for cocktails and gossip about their industry. People don’t talk about their workforce as a community. All the citizens of a country are not a community, but they might check out a community theater performance at the community college or community center. An accountant’s clients are not a community; the customers of a department store are not a community. The word implies natural affinity and voluntary participation. (Is the mafia a community? A prison population?) Today the word “community” is stretched out beyond recognition as it is applied to those who use the internet—that is, more than half the world’s population.

In internet discourse, “community” has come to be known as the plural form of “user.” I guess that “users” sounds cold and inactive to the likes of Mark Zuckerberg, who addressed a manifesto-like letter in February 2017 “To our community.” The letter states Facebook's mission of “bringing people together and connecting the world.”<sup>1sup It also contains sixteen references to the “global community,” by which Zuckerberg means the Facebook users who represent a quarter of the world. Struck by the term, I looked up “global community” on Google Ngram Viewer, and it can be found in scarcely 0.0000001% of books in history. The phrase was still an oxymoron in the twentieth century, although it seems to have picked up sometime around 2003, when Bill Clinton wrote in an International Herald Tribune opinion piece that the “great mission of the 21st century is to create a genuine global community.”<sup>2sup

Installation view of Heather Dewey-Hagborg, Radical Love: Chelsea Manning, 2015. World Economic Forum, 2016

Facebook has every reason to try to convince its users that they are a “global community,” since the service has successfully cannibalized actual community functions like community newsletters and community calendars in communities around the world. But what would a real “Facebook community” look like, in the traditional sense of the word? I imagine it would involve people coming together, as they do for community town halls and community school board meetings. Users, as a collective, would advocate for greater privacy protection, a stricter anti-harassment policy, or request further transparency about advertising on the platform, among other activism that would hold the social network accountable for its actions.

We see something like that in the Wikipedia community: a group that does not include its millions of daily readers, but is more intimately formed in groups of editors, meet-up participants, and other activists, all of whom, with the exception of the Wikipedia Foundation’s staff, are volunteers. They are united by a shared interest (Wikipedia) and a shared goal (promoting factual information). To be clear, the word “community” never suggests an altogether positive experience. A community is usually guarded rather than welcome to all, often due to both the implicit and explicit behaviors of its members. Communities have hierarchies and are subject to abuses of power like bullying, blackballing, bigotry, and harassment. Wikipedia’s crowdsourced gatekeeping is a process already structured toward excluding rather than including others. Pedantry is basically required of its participants.

“The way that Wikipedia is totally transparent makes it totally opaque,” Jacqueline Mabey, cofounder of the Wikipedia editing project Art+Feminism, explained to me. It is easy for a new user to feel overwhelmed by the rules and meta-pages, especially if more experienced editors respond to them with “procedural gobbledygook” over simple mistakes. Then again, rules are how a community keeps its members safe. Mabey points out that Wikipedia’s anti-harassment policies help to “create a welcoming community” and make the organization more inclusive where it counts: people interested in promoting factual information, who might also happen to embody demographics (women, people of color, queer and trans) that are underrepresented among editors.

Chelsea Manning digital rendering from DNA, gender parameter assigned female.

Wikipedia editors are semi-anonymous, identified only by usernames or IP addresses. In recent years, researchers have connected some of these IP addresses to organizations and agencies using Twitter bots. For example, the account Parliament WikiEdits updates every time an edit is made from an IP address connected to the Houses of Parliament. There are similar bots tracking changes made at meeting places of elected officials in Australia, the Netherlands, Chile, and several other countries.

In the summer of 2014, CongressEdits updated with particularly inflammatory activity. Someone using a computer at the House of Representatives was vandalizing pages of prominent trans women like Chelsea Manning. Manning herself was incarcerated at the time and unable to defend her reputation on the platform. “An obvious transphobe is using this IP to edit the article on transphobia, justifying it with rhetoric commonly used by transphobes,” wrote a Wikipedia editor who flagged the account. “They claim to be acting with the explicit permission of a US Representative, which is either an outright lie (and therefore more reason to block the IP) or true (and therefore more reason to block the IP).” Another editor then moved to block the IP address for a month. This meant that anyone trying to edit Wikipedia anonymously from that famous building was banned for a month. Members of Congress were now implicated in this troll’s offenses, and all because Wikipedia editors were following procedures.

Here is an example of otherwise anonymous users coming together to kick out a pest and keep a space safe. Maybe they didn’t know one another by name or face, but there’s no greater show of community than that.

Footnotes

- Mark Zuckerberg, “Building Global Community,” Facebook, February 16, 2017.

- Bill Clinton, "A Global Community: Defining the Mission of the 21st Century," The New York Times, November 6, 2003.