What Is Your Murakami Moment?

by Ruida Zhu

Featured image

Installation view, Takashi Murakami: The Octopus Eats its Own Leg, MCA Chicago, Jun 6–Sep 24, 2017. Work shown: Takashi Murakami, And Then, And Then, And Then, And Then, And Then (Red), 1996. Acrylic on canvas mounted on board; two panels, overall: 118 x 118 in. (300 x 300 cm). Collection David Teiger Trust. © 1996 Takashi Murakami/Kaikai Kiki Co., Ltd. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Nathan Keay © MCA ChicagoAs the social media intern at the MCA, I am charged with creating a buzz around the art and events at the museum on some of the most highly-consumed media platforms. However, when entrusted with highlighting Takashi Murakami (who creates his own buzz), I found myself, and many of my friends, slightly unconvinced by the world he has created. Having grown up in China, I saw Murakami as an imposing cultural figure; he appeared in the art world, in pop songs, and in fashion news. While it seemed like most people had embraced him, there was also a large opposition that claimed he was too commercial, simple, and ambitious—total contradictions to traditional Asian values. This impression greatly affected the way I saw Murakami’s exhibition at the MCA. Given the social media task at hand, I needed to know if there was another way in. So, fully equipped with knowledge absorbed from the catalogue and curator-led tour as well as Buddhist memories with my grandmother, I ventured out of the virtual world to prove to myself and the people I know that, in terms of contemporary art, sometimes trying to understand is more important than liking it.

Things did not go as I anticipated though. I never expected to see any spark between the people I brought to the museum and the exhibition.

Video

The first friend/case study I brought to the museum is a typography maniac. He spent most of his time in the education gallery, which presents the process of creating the mammoth arhat painting in the last room. (An arhat is a student of Buddha who travels around the country to save and heal people.) The question he kept asking was, “How can they always get the right color on the right space when applying silk-screen ink many times on such large-scale canvases?” He told me that his failing silk-screen experiences in the past made Murakami’s teamwork almost magical.

Installation view, Takashi Murakami: The Octopus Eats Its Own Leg, MCA Chicago, Jun 6–Sep 24, 2017. Work shown: Takashi Murakami, 69 Arhats Beneath the Bodhi Tree (detail), 2013. Acrylic, and gold and platinum leaf on canvas mounted on board; 10 panels, overall: 118 1/8 x 393 ¾ in. (300 x 1,000 cm). Collection Lune Rouge. © 2013 Takashi Murakami/Kaikai Kiki Co., Ltd. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Nathan KeayThen I brought a friend who is Catholic, but born and raised in a region where most people are Buddhist. She was also extremely interested in the 100 Arhats and 69 Arhats paintings, but for religious reasons. She reflected on hearing that Murakami created as many arhats as possible—far beyond the 16 arhats tradition—to represent his pain and his wish to help the Japanese affected by the 2011 earthquake and subsequent nuclear disaster at Fukushima. She is very versed on the God of Catholicism but looking at this work made her think an ultimate question: who creates the “god” in Buddhism? There began an unavoidable comparison in her head between the two religions and she became flooded by memories of her struggle in the religious choice during growing up.

Installation view, Takashi Murakami: The Octopus Eats Its Own Leg, MCA Chicago, Jun 6–Sep 24, 2017

Photo: Nathan Keay © MCA ChicagoThe third person I brought to the exhibition is a math PhD student at the University of Chicago. While definitely one of my smartest friends, she does not have a special interest in art. As we were viewing the evolution of Murakami's alter ego, Mr. DOB, she stopped at three paintings where Mr. DOB's shape was deconstructed. She blurted out, “Is this Klein’s Bottle?” We looked at the label and the title of the series was Klein's Pot! While she tried to explain the concept of the Klein bottle to me, I was still far from understanding and she dismissed the lesson saying, “Never mind. Klein's bottle is now more like the conceptual art, but not mathematics anymore.”

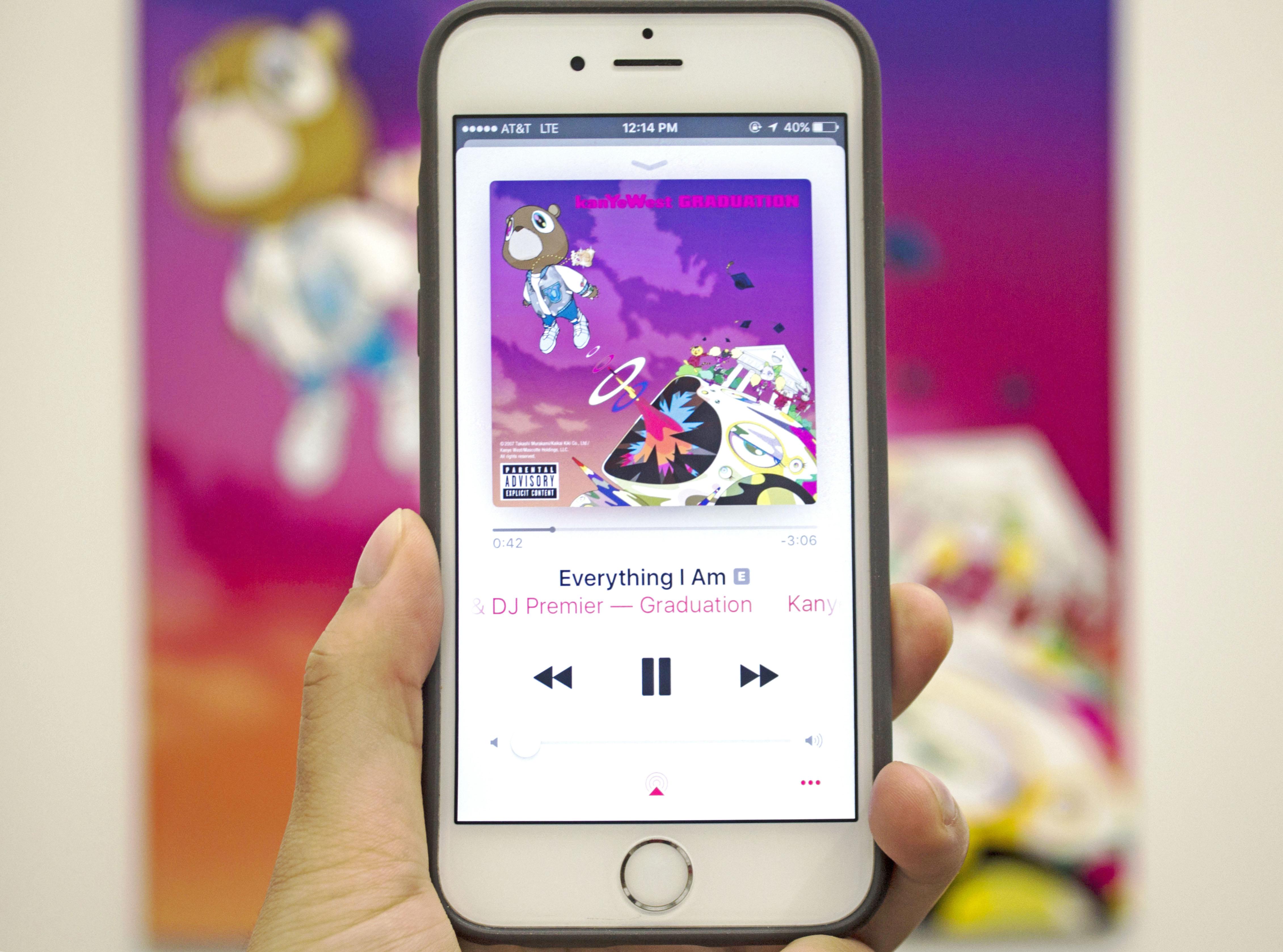

Though I was book smart when it came to the exhibition, I hadn't accounted for personal experience when it came to interpretation. Contemporary art can seem unapproachable, but I discovered that in contemporary art there is an opportunity for anyone to find a moment of enjoyment or a connection. Through my visits I realized how many different ways people with different backgrounds can respond to a work—and you can learn from those differences. Each Murakami moment with my friends gave me new insights into Murakami's work: I had never given much thought to silk screening, but now I pay attention to this technique; as an atheist, I never thought to look closely at a religion, or to compare one to another; and though I might apply the shape of Mr. DOB to Murakami's Superflat theory, I would never have guessed that the title of the work was based on a mathematical theory. My own moment came in the form of his pop culture collaborations—something I was so weary of at the beginning. Murakami designed the Graduation album cover for Kanye West, and that work reintroduced me to Kanye's music at a time I needed it. As I faced my own graduation, and the end of summer and my internship, I found great consolation in his lyrics and melodies as well as in the evolution of the cover—a dropout bear on the bench, to a bear wearing a suit, to Murakami's conceptual bear rocketing to colorful space. Similar to the exhibition's titular work, which points to sacrifice as a form of rebirth, Kanye taught me that on your way to graduation, whatever you are struggling with is indeed what is shaping you.

That must be the beauty of contemporary art. No matter what theory or approach the artist is using, no matter what you are interested in, believe in, or excel at, you can find a connection.

Takashi Murakami, Graduation, 2017, with cover art of Kanye West's Graduation, 2007

Image courtesy of the authorCall to action

What’s your Murakami moment? Share with us on Facebook, Instagram, or Twitter!