Moving the Medium Forward

Featured image

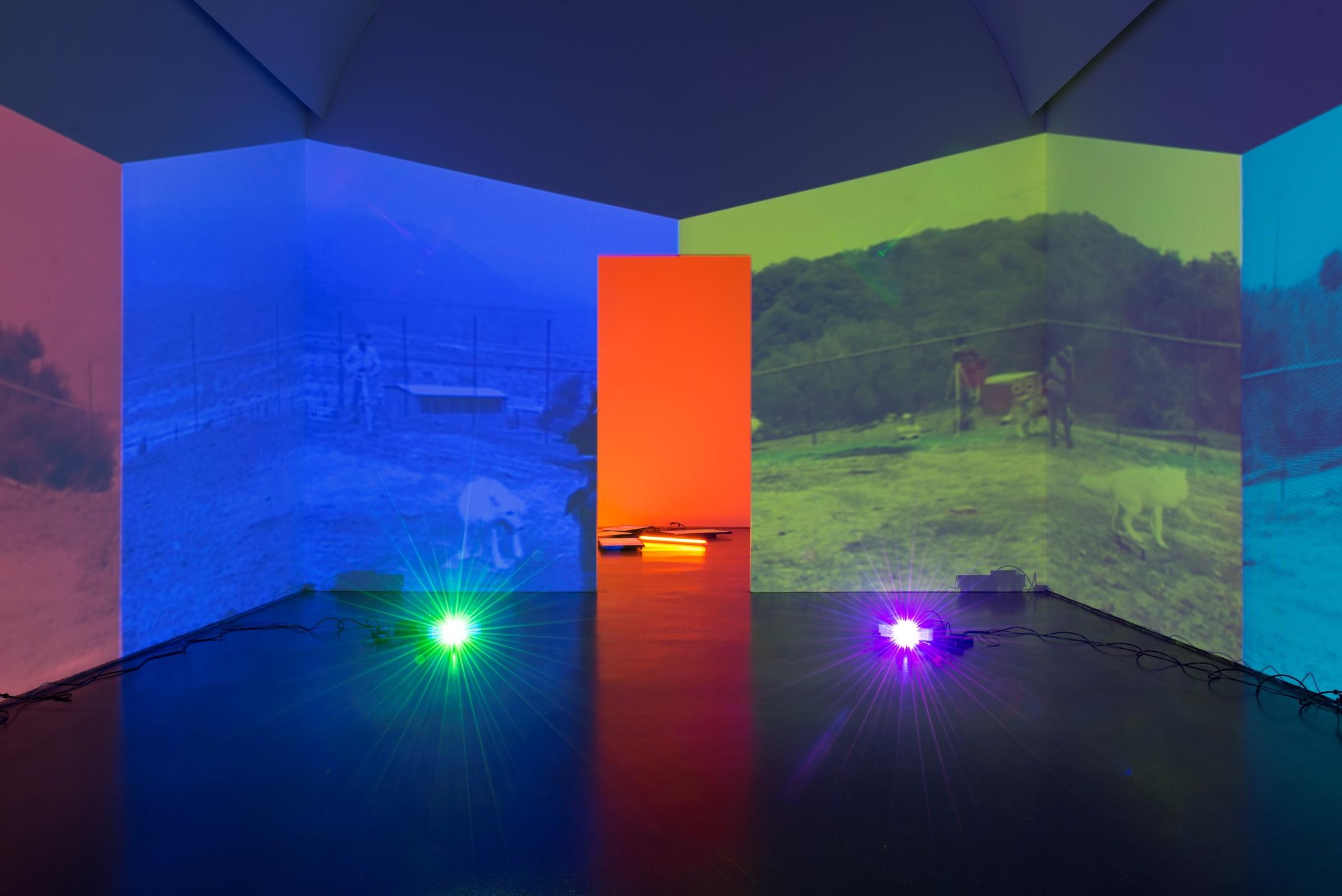

Installation view, Diana Thater: The Sympathetic Imagination, MCA Chicago, Oct 29, 2016–Jan 8, 2017

Photo: Nathan Keay © MCA Chicago

Joyce Pensato, Silver Batman II, 2012. Enamel on linen; 72 1/4 x 64 x 2 in. (183.5 x 162.6 x 5 cm). PG2012.3. © 2012 Joyce Pensato

Photo: Nathan Keay, © MCA Chicagoblog intro

One of the many ephemeral materials created by the Guerrilla Girls was a photocopy of a dollar bill divided by a dotted line into one-third and two-thirds, with the caption, "Women in America earn only 2/3 of what men do. Women artists earn only 1/3 of what men do." While sexism continues to pervade the art world, female artists in two exhibitions currently on view at the MCA are challenging this boys-only sensibility with the mastery, experimentation, and innovation of their chosen medium.

Diana Thater, whose exhibition closes Sunday, is a Los Angeles–based video and installation artist, who revolutionized film and video in the 1960s and 1970s. Rather than working with the technological constraints of the media like many of her contemporaries, she pushed the mediums beyond their limits, pulling projectors out from their hiding places, playing with a limited spectrum of seven colors, and rejecting the rectilinear framework imposed by standard monitors. Thater's works blur the lines between architecture, sculpture, and video, and her installations challenge how video can and should be experienced. Listen to her discuss the role art history played in her artistic choices in the audio excerpt on this page.

Similarly, the 10 artists featured in Riot Grrrls have rejected the masculine associations of abstract art, creating big and unapologetically bold nonrepresentational paintings of their own. Named after the feminist punk movement of the 1990s, the exhibition pairs pioneering artists who worked in the 1970s and 1980s with a younger generation of artists they influenced, continuing a conversation whose spirit is captured in this statement from the Riot Grrrls’ manifesto: "BECAUSE viewing our work as being connected to our girlfriends-politics-real lives is essential if we are gonna figure out how [what] we are doing impacts, reflects, perpetuates, or DISRUPTS the status quo."

Diana Thater Audio

Audio Transcript

I thought that the earliest works made in film and video—made from the early sixties through late sixties—attacked really interesting problems, and because the medium was so imperfect, they dealt with all of its flaws.

If you think about Joan Jonas in Vertical Role, for example, you have an artist dealing with a medium that's been broken or a medium that doesn't work quite right; and Nam June Paik did a lot of things working with repetition and fooling around with equipment and making equipment do things it wasn't supposed to do.

And I was – wanted to go back and pick up that ball and carry it forward. And I felt that people who were working in film and video when I was in school and right after I was in school were not moving it forward. And they weren’t exploring the limitations of what the equipment could do, what the technology could do, what cameras can do.

And they weren’t exploring what I really wanted to explore,

which was time and space—the time signature of video and the sort of spatial signature of art—and I wanted to bring those two things together.

That’s another reason I started working in moving images is because I wanted to intertwine time and space in the work of art, and that’s a very difficult thing to do.

I thought I can do it through installation and through projection and architectural installation. And in that way, I could bring sort of time and space together into a kind of abstract experience for the viewer.

Video

Diana Thater, excerpt from A Cast of Falcons, 2008. Four video projectors, display computer, and two Source Four lights; overall dimensions variable. © Diana Thater. Courtesy of the artist and David Zwirner, New York/London.

Installation view, Diana Thater: The Sympathetic Imagination, MCA Chicago, Oct 29, 2016–Jan 8, 2017

Photo: Nathan Keay © MCA Chicago

Installation view, Diana Thater: The Sympathetic Imagination, MCA Chicago, Oct 29, 2016–Jan 8, 2017

Photo: Nathan Keay © MCA Chicago

Video

Diana Thater, excerpt from Delphine, 1999. Four video projectors, nine-monitor video wall, five players, and four LED Wash Lights; overall dimensions variable. © Diana Thater. Art Institute of Chicago, Donna and Howard Stone New Media Fund, 2005.93.