4 Things

by Andrew Yang

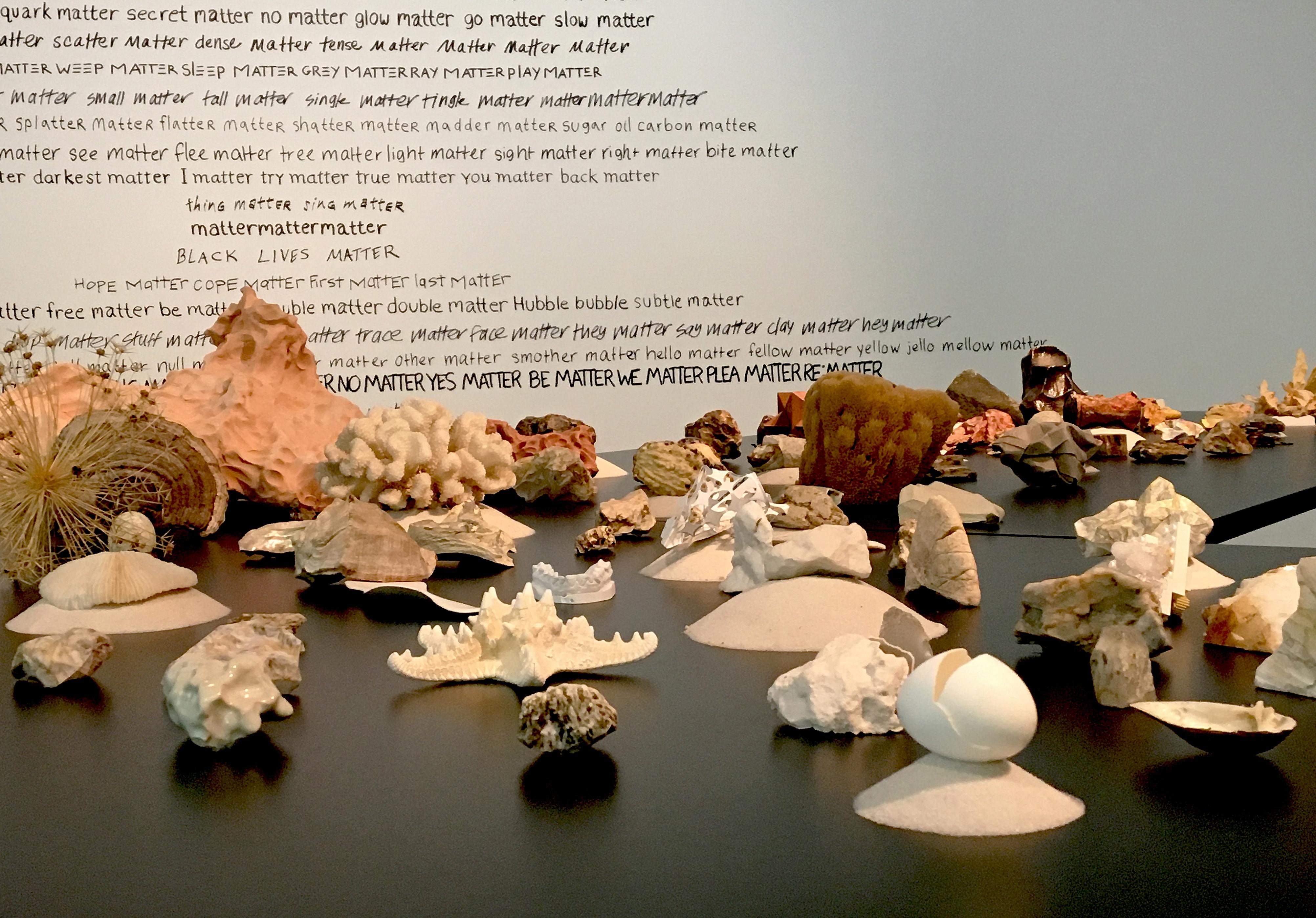

Featured image

Installation view, BMO Harris Bank Chicago Works: Andrew Yang, MCA Chicago, Jul 26–Dec 31, 2016

Photo: Shauna Skalitzky © MCA ChicagoAndrew Yang participates in our 4 Things series by sharing four things that influence his art and practice. See his work in the current BMO Harris Bank Chicago Works exhibition, on view through December 31.

Rocks

There is nothing so commonplace and varied as rocks. From pebble to boulder, sand grain to building stone, they are almost always at hand with their diverse shapes, sizes, colors, textures, patterns, and weights. When I feel like I need to re-center myself, looking at rocks on the ground and collecting a few usually does the trick. They are one of the few objects that have a form that is completely literal and abstract at the same time. A rock is an example of what might be called the “boring sublime.” Despite being so everyday and having no economic value, they are utterly unique objects—no two rocks are the same; each takes its present form only after a process of transformation that took millions of years. A collection of rocks is really a collection of moments, a kind of visual journal of aesthetic choices (to pick up or not to pick up) mixed with the utter chance of finding a particular rock.

Science Magazines

Science magazines are mind candy, but nutritious. Most focus on recent discoveries, so (unlike most news) I feel like I'm not only learning new information, I'm also taking part in a discussion on questions and ideas beyond the horizon of my habitual imagination, things that I would likely never consider. And unlike science fiction, these phenomena are active facts in the world—if not also in my own cells, brain, and daily life. Becoming knowledgeable about my ignorance is somehow exciting. Conceptually, a lot of my projects are fed by the ideas I come across in such magazines, but the pages are also a rich visual resources and I actively collage with the images I find in publications like New Scientist, Nature, and National Geographic as a way to play with new ideas as well as to simply keep my brain and fingers nimble.

Eggs

Which came first, the chicken or the egg? This kind of question keeps me up at night. I grew up on a small farm with chickens, ducks, geese, and their eggs. We would collect them in the coop, nurture them to hatching in tabletop incubators, and of course fry them up in a hot pan. It was full circle, or perhaps I should say, full oval. A bird egg is an almost-perfect sculptural thing, a fragile ellipse that also happens to contain everything necessary to turn its amorphous yolky insides into a creature that hatches out as lovely as it is vital. It is a quintessential object of Origins. When I hold an egg I can’t help but think not only of the possible bird but also of its reptilian ancestors; birds, after all, are the only dinosaurs still alive. Bullfrog eggs are something else all together: strings of floating translucent luminosity. The tadpole’s metamorphic acrobatics are admirably transparent, a mystery for all to see (which itself might be a good definition of art?). Given all of this, eggs show up in my work in different ways—visually, metaphorically, and otherwise. When I crack a chicken egg into a bowl, a miniature nutritive sun is staring at me, and I, in turn, am staring at the sun.

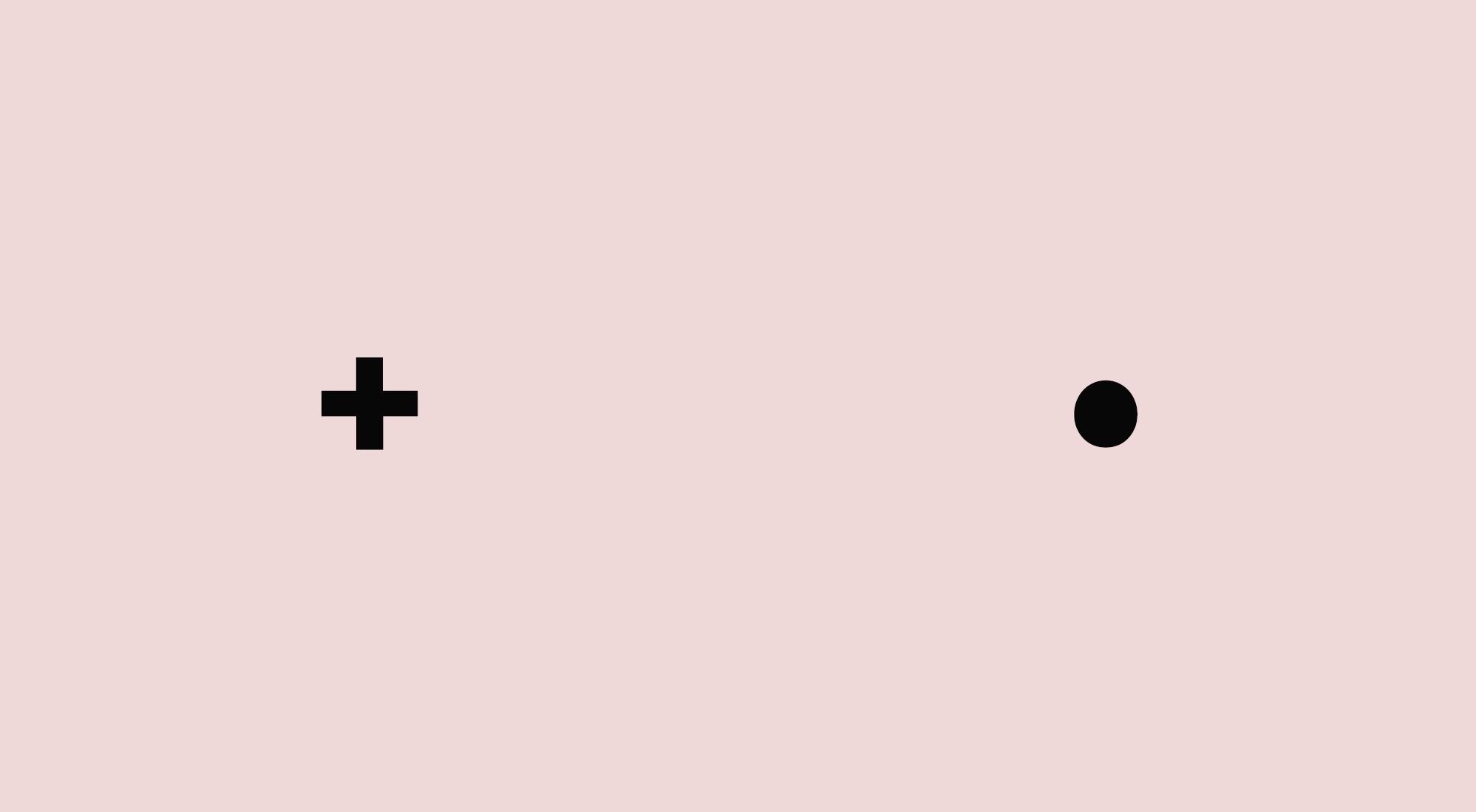

Optical Blindspot

At the back of every person’s eyeball is a hole where the optic nerve dives back into their brain. Because of this, there is also a hole in the retina, a place where we can’t capture light and hence there is “blindspot” in our vision. We don’t usually notice it because the visual field of our two eyes overlap and our brains supposedly try to perceptually “fill in” the spot’s visual gap. Either way, there is a little trick to make the blindspot visible to ourselves. Every time I do it, I am surprised, so it never gets old. There is a strange sensation of misperception that mixes with an intellectual recognition that our experiences rely on a body that is very much a physical contraption. To see myself “not seeing” is wonder filling, mildly spooky, and a sort of joke on myself all at once. The feeling I have in that moment is what I aspire to in making and looking at art.

EXPERIMENT: Close your right eye. With your left eye look at the circle. You should see the plus sign peripherally. Now as you continue to look at the circle with your left eye, move your head closer and closer to the screen, adjusting to the place where you see the circle but no longer see the plus sign. Once you are about 12 to 17 inches away, the plus sign should visually disappear. You have just seen yourself not seeing.

Image captions

All photos, unless otherwise noted, are © Andrew Yang, courtesy of the artist.