Kerry James Marshall, Renaissance Master

Rosie May

Featured images

Kerry James Marshall, Vignette, 2003. Acrylic on fiberglass; 72 x 108 in. (182.9 x 274.3 cm). Defares Collection

Courtesy of the artist and David Zwirner, Londonblog intro

Today Kerry James Marshall: Mastry opened at the Met Breuer. Situated among the extended art history of an encyclopedic museum filled with so-called old masters, Mastry's installation in New York will reveal Kerry James Marshall's works' deep connection to the past. We asked our Associate Director of Education: Public Programs and Interpretive Practices, Rosie May, to reflect on Marshall's references to art history in his works.

on Renaissance masters

I've spent much of my career as an art historian absorbed in the Italian Renaissance surrounded by the works of masters like Masaccio, Donatello, Michelangelo, and Caravaggio. While preparing for the Mastry exhibition, I was struck by the similarities between Kerry James Marshall and his Renaissance forerunners. They are all driven by a desire to bring stories to life by creating recognizable figures in relatable settings. They have also diligently studied and honored their debt to their predecessors but brought a contemporary spin to their work.

Renaissance artists worked throughout their careers to represent Christian saints and scenes from the Bible with realistic human figures. Creating convincing, three-dimensional figures was a skill that had been lost after the fall of the Roman Empire so Renaissance artists turned to ancient Greek and Roman sculpture. They often made trips to Rome to learn how to create lifelike human forms by studying the remains of ancient sculpture.

Featured images

Masaccio, The Distribution of Alms and Death of Ananias, 1425–28. Fresco; 230 cm × 162 cm. Brancacci Chapel.

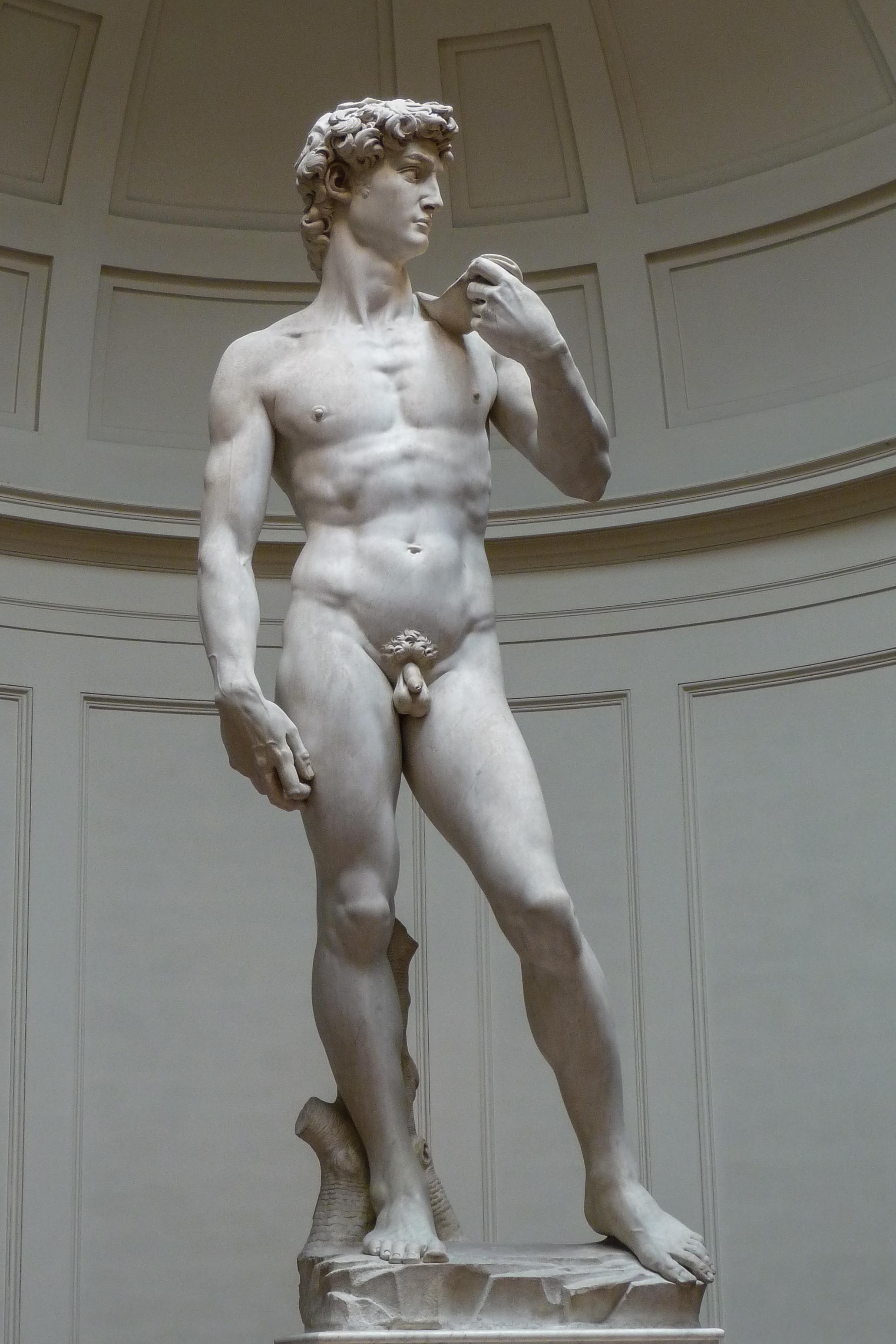

Michelangelo, David, 1501–04. Marble. Galleria dell'Accademia

Photo: Jörg Bittner Unnaon reflecting on the past

They focused not only on the forms of the bodies but also on the poses that their predecessors used to animate the works. Yet Renaissance artists added new elements: human emotions and contemporary settings. For example, Masaccio set the biblical scenes in his frescoes in the streets of Northern Italy and dressed his figures in contemporary clothing. Similarly, Michelangelo represented the biblical hero David preparing to go into battle with Goliath by giving him the body of an ancient Greek or Roman sculpture of a god, but added a human reaction—an expression of anticipation and determination with a penetrating gaze and a furrowed brow. Caravaggio took the advances even further by taking people off the street and having them pose as models for biblical figures. He painted them with their lined and tired faces and dirty hands and feet demonstrating that holy figures looked just like everyone else.

Walking through Marshall’s exhibition, I could see echoes of the Renaissance artists in his work and, like these old masters, he produced paintings that paid homage to his predecessors but created new meanings.

Masaccio, The Expulsion from the Garden of Eden, 1426–27. Fresco. Cappella Brancacci, Santa Maria del Carmine, Florence

on Adam and Eve in art history

In Vignette

Donatello, David, c. 1440s. Bronze; 62 in. (158 cm). Museo Nazionale del Bargello

Photo: Miguel Hermoso CuestaFeatured image

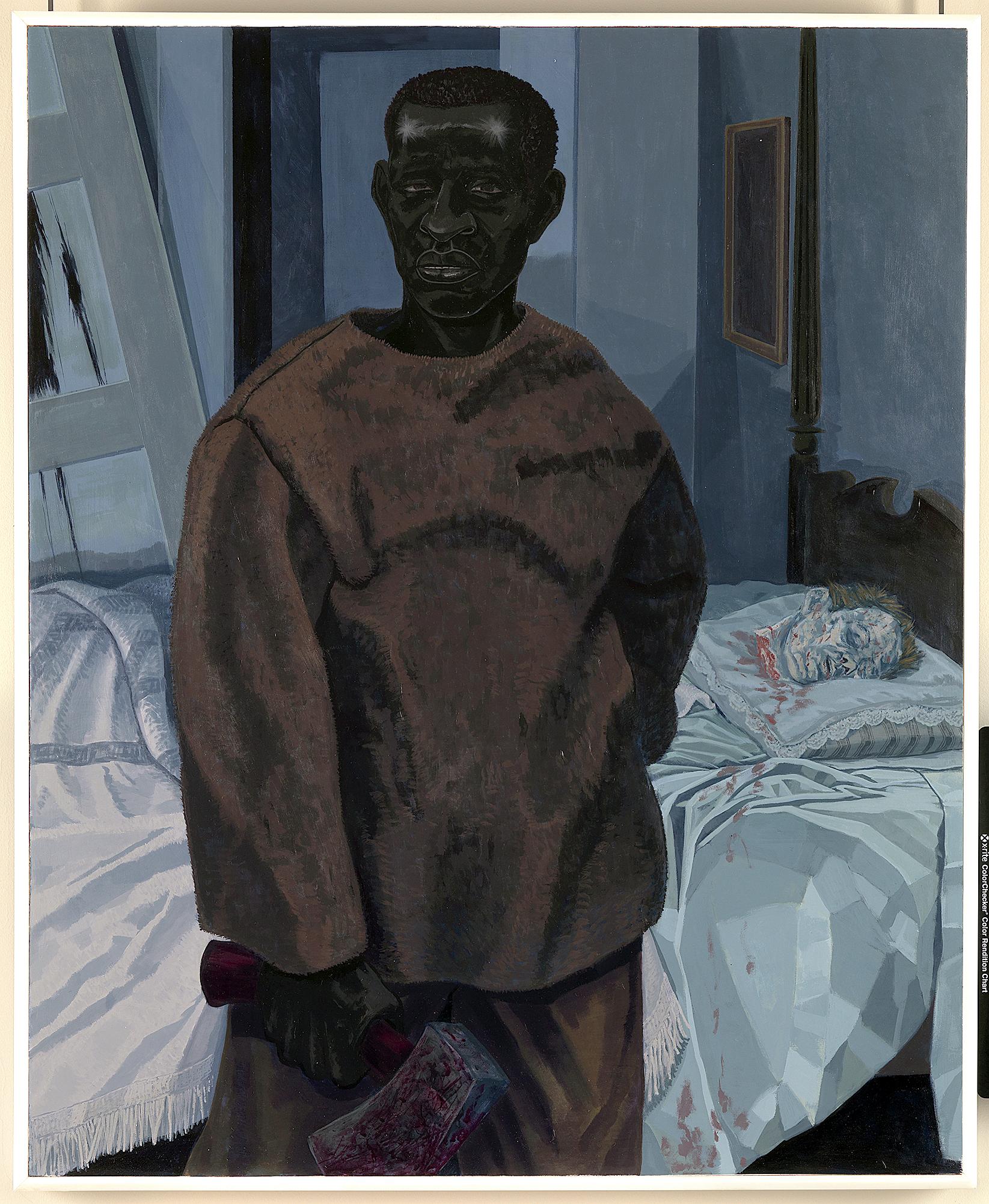

Kerry James Marshall, Portrait of Nat Turner with the Head of his Master, 2011. Oil on canvas; 36 x 29 1/2 in. (91.4 x 74.9 cm). Private collection, courtesy Segalot, New York

Photo: Bruce M. White © MCA Chicagoon sampling from the past

Much like the Renaissance artists would adopt the poses of ancient sculpture to demonstrate their knowledge of their predecessors, Marshall's Portrait of Nat Turner with the Head of His Master

In this painting, Marshall also draws on a later generation of Renaissance artists like Caravaggio and Artemisia Gentileschi who created more dramatic and explicit scenes in their work. Caravaggio painted several works depicting David triumphantly holding the bloodied head of Goliath; and Gentileschi made paintings of the biblical heroine Judith who saved the Jewish people from the threatening Assyrian army by seducing and beheading the general Holofernes. Marshall took the gory realism of these paintings, with their severed heads and bloodied axes, to revisit the brutal reality of Turner’s deed but also to recast him as a biblical hero.

Caravaggio, David with the Head of Goliath, c. 1610. Oil on canvas; 49 × 40 in. (125 × 101 cm). Galleria Borghese

Artemisia Gentileschi, Judith Slaying Holofernes, c. 1614–20. Oil on canvas; 78 × 64 in. (158.8 × 125.5 cm). National Museum of Capodimonte, Naples

on being a master

To explain these Renaissance influences on his art, Marshall has reflected that "one of the senses you get from the work that we call old-master works was that the work was based on their knowledge of some things . . . that they seemed to know and they used that knowledge to construct these pictures . . . and so what I was always intrigued by what it was they knew that allowed them to make those kinds of pictures." In looking closely at his works I recognized much of what I studied of Renaissance in his paintings; I could imagine him studying and absorbing the work and techniques of his seventeenth-century predecessors. And like the Renaissance painters before him, by connecting his meticulously painted work to a larger tradition while addressing contemporary issues, he has become a modern master whose work will inspire future generations.