Unpacking Concrete Traffic

Featured image

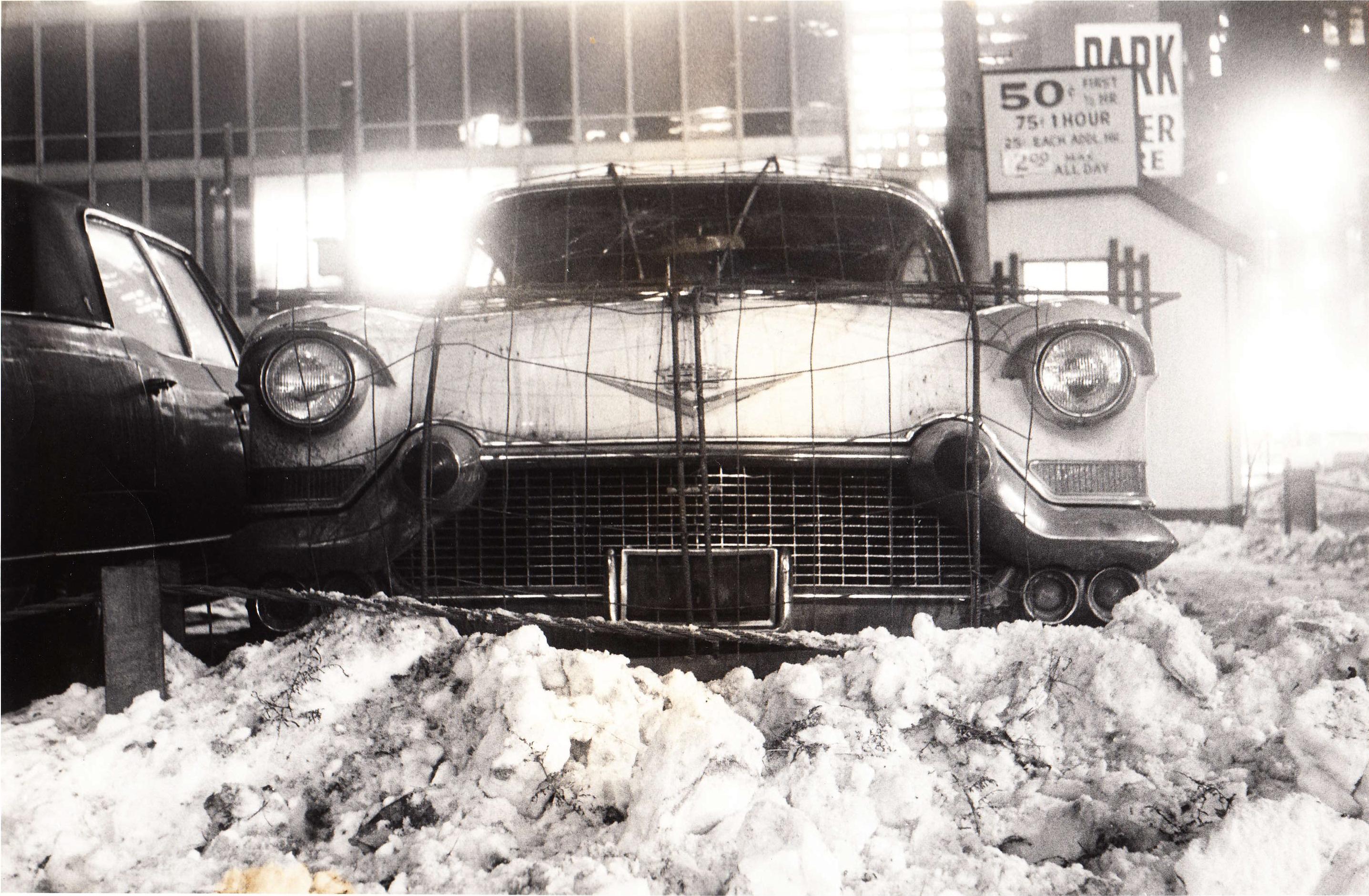

The Cadillac in the parking lot shortly before the pour, Jan 1970

Photo: David H. Katzive © MCA Chicagoblog intro

After nearly eight years of being in storage and under restoration, Wolf Vostell's Concrete Traffic (1970), one of the earliest works commissioned by the MCA, returns to public view tomorrow, September 30, with a procession that begins on the MCA’s plaza and ends at the University of Chicago campus. To mark this return, MCA Library Director Mary Richardson, who was part of the conservation workshops, reflects on the history and importance of this monumental work.

Educational video by David Katzive.

on Concrete Traffic

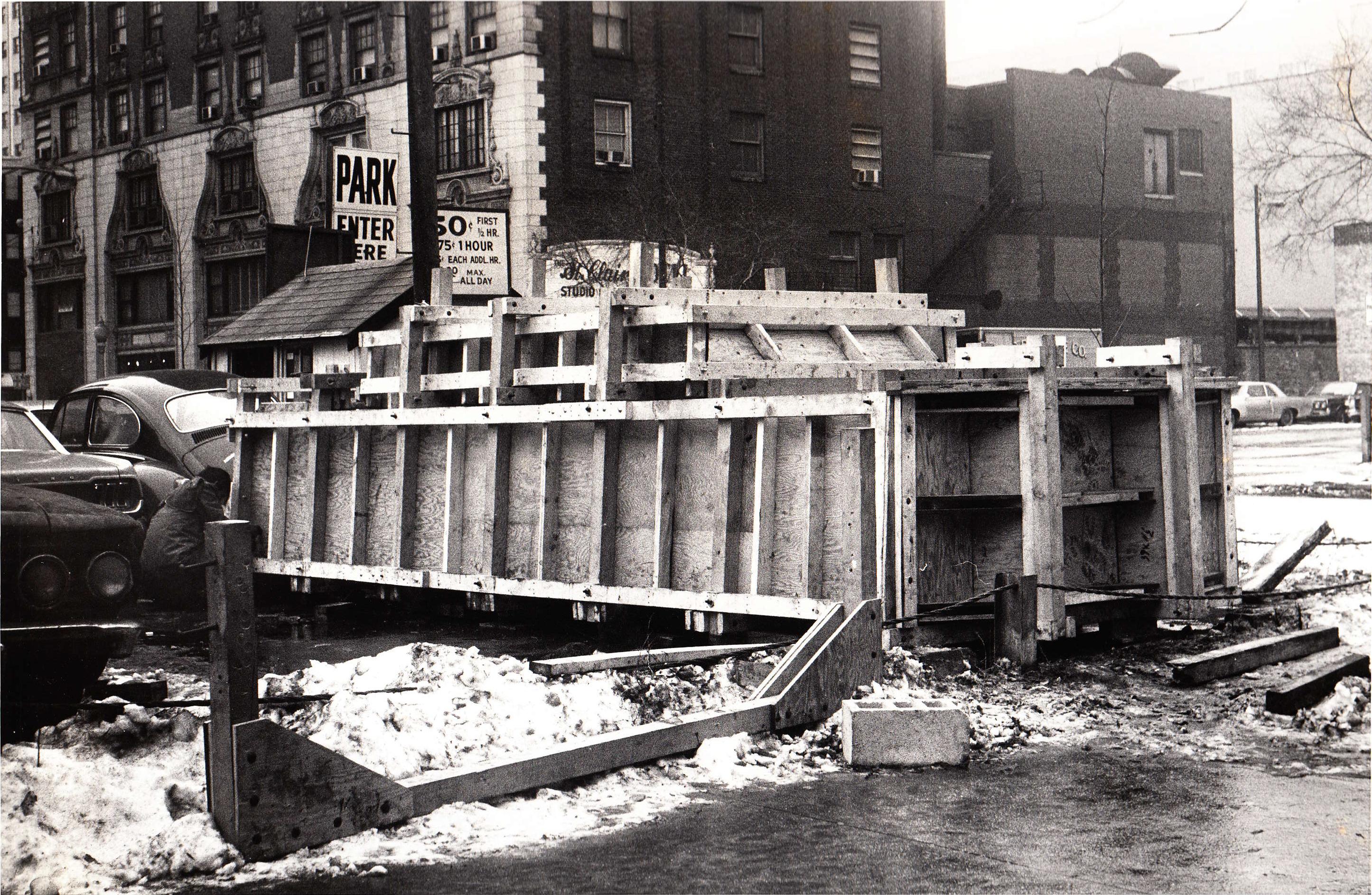

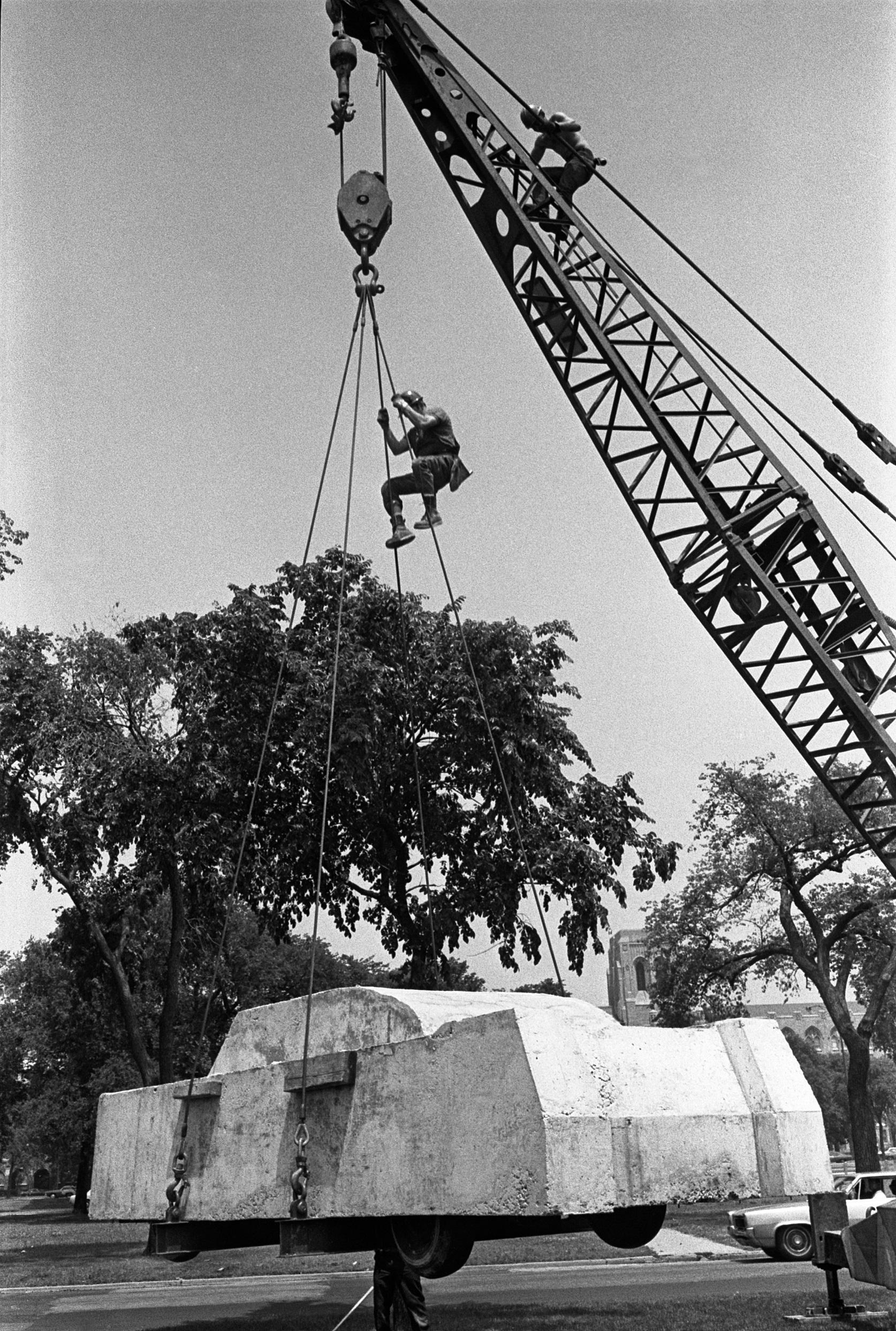

On January 16, 1970, a crowd gathered at a parking lot on the corner of Ontario and St. Clair to watch MCA staff entomb a 1957 Cadillac Deville in 16 tons of concrete. With very general directions left by the artist, Wolf Vostell, MCA staff prepared for the pour by wrapping the car in rebar and steel mesh and building a plywood mold in advance. On the day of the pour, they towed the car to the lot and assembled the mold around the car. Then a cement mixer pulled up, and staff evenly distributed the cement over the car. Six days later, the concrete had set, and staff removed the mold revealing Concrete Traffic. For five months the sculpture remained parked in the lot surrounded by cars and everyday traffic until it was hoisted onto the bed of a truck and transported down the Dan Ryan Expressway to its new home outside of Midway Studios on the University of Chicago campus, where it remained for 40 years.

Despite its monumental presence, Vostell conceived of Concrete Traffic as more than just a sculpture; he called it an “Instant Happening,” which “isolates an object or action and, by concentrating our full attention on it, forces us to question the whys and wherefores behind it. Suddenly, a man on the street, who is not quite expecting it, is confronted with something ordinary that is not quite right. Something disturbs his understanding of reality. His reactions are tested. He must begin questioning.”1sup Making and exhibiting Concrete Traffic in a public place was essential to Vostell's approach and to the meaning of the work. If it were presented in a gallery or made in a studio like traditional sculpture it would lose some of its power and meaning.

Wolf Vostell and James O'Hara, the fabricator of the mold, Jan 1970

Photo: David H. Katzive © MCA Chicago

Concrete Traffic after the pour as the concrete is setting, Jan 1970

Photo: David H. Katzive, © MCA ChicagoFeatured image

After the mold was removed, Jan 1970

Photo: David H. Katzive, © MCA Chicagoon the artist’s process and goal

Vostell used the word Dé-coll/age to describe his artistic philosophy. He would destroy and reuse familiar objects, such as televisions and cars, to explore and question modern culture. He often dissolved images from magazine pages with chemicals and created décollages (where the artist cuts away, tears, or removes) from posters and print ad. He used these nontraditional techniques and materials to jar people and grab their attention, believing he could create change “through the disturbance of the familiar.”2sup

With Concrete Traffic, Vostell wanted to prompt people to really think about cars—what they mean, and how they impact us. As the MCA's first director, Jan van der Marck, wrote “Vostell . . . is now involved with environmental problems and the concrete car gives us a glimpse of the fantastic traffic jam in which the world someday may come to a standstill.” Vostell rendered the automobile immobile by filling it and encasing it with concrete (a material that dominates the urban landscape)—the concrete jammed the engine, seeped into the wheel wells, busted through the windshield, and flooded into the passenger compartment. He mummified the car, simultaneously preserving and transforming the car from a functional mode of transportation into a mausoleum, asking passersby to pause and reflect on cars, concrete, and the way we live.

View of Wolf Vostell's Concrete Traffic being transported to U of C, Jun 1970

Photo © MCA Chicago

View of Wolf Vostell's concrete Traffic being transported to U of C, Jun 1970

Photo © MCA Chicagoon the meaning of the artwork

Vostell's provocation is just as relevant and urgent today as it was in 1970. Cars have quintessentially American associations. They evoke the ingenuity and efficiency of the assembly line, the American Dream, and the freedom of the open road. Vostell's transformation of the Cadillac calls into question the flip side of these associations: our mass consumption, our fetishizing of material objects, and our concepts (or misconceptions) of freedom. Instead of cars freeing us, we often spend most of our time in traffic feeling stressed and trapped, rather than on the open road. In the 1960s and 1970s, people were starting to question the environmental impact of cars and consumerism. Since then, these concerns have increased as we witness the effects of climate change and seek solutions with new energy sources, alternative modes of transportation, and environmentally and socially conscious design. With Concrete Traffic's return to the University of Chicago, it will continue to occupy a public space and provoke us to think about the world around us.

View of Wolf Vostell's Concrete Traffic being installed at U of C, Jun 1970

Photo: Jean-claude LeJeune © MCA ChicagoBibliography

Works Cited

- Wolf Vostell, undated MCA Press Release: Lecture/Film Demonstration.

- Wolf Vostell and Dick Higgins, eds., Fantastic Architecture (Something Else Press, 1970).