René Magritte Has Changed

Featured image

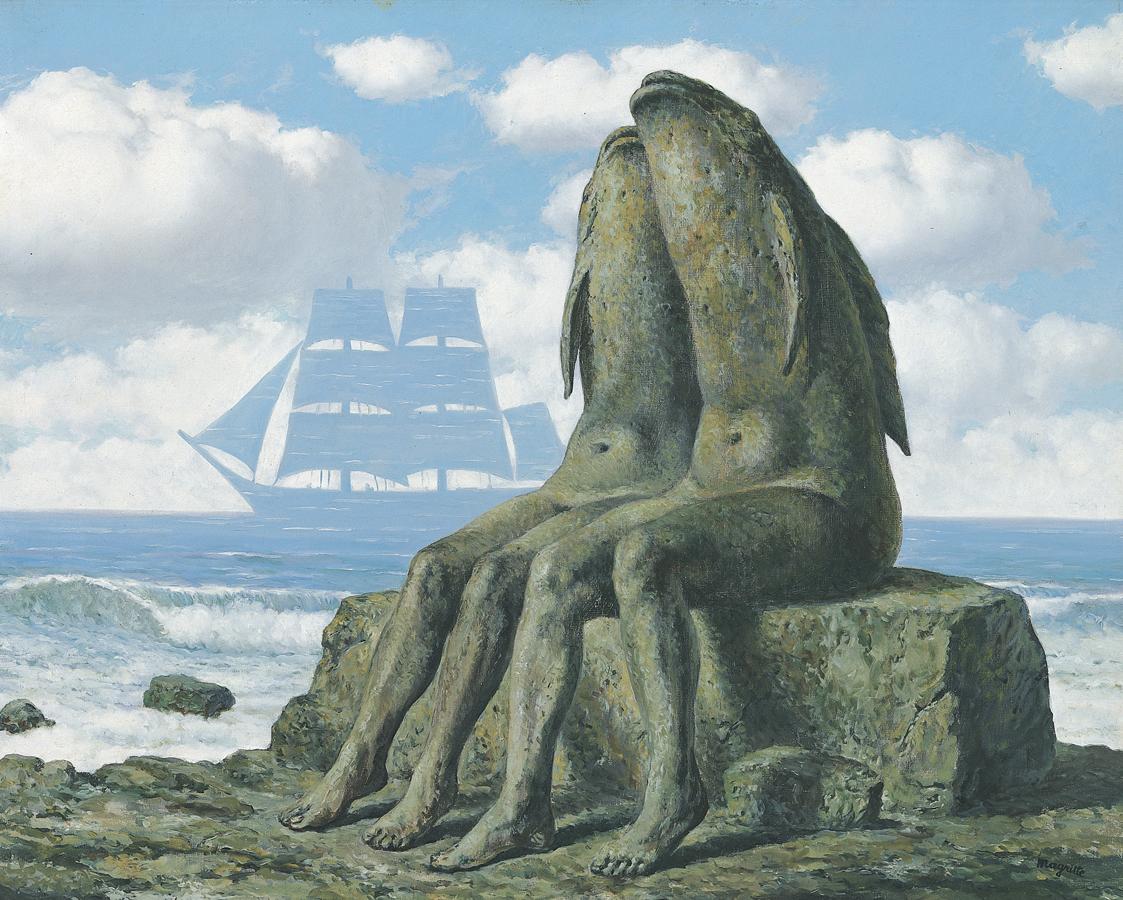

Rene Magritte, Les merveilles de la nature (The Wonders of Nature), 1953. Oil on canvas; 30 1/2 x 38 5/8 in. (77.5 x 98.1 cm), framed: 38 1/4 x 46 1/4 x 2 1/2 in. (97.2 x 117.5 x 6.4 cm). Collection Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago, gift of Joseph and Jory Shapiro, 1982.48. © 2015 C. Herscovici/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Photo © MCA Chicagoon Magritte’s works

Earlier this month, University of Minnesota Press published the book René Magritte: Selected Writings, coedited by Eric Plattner and me. The first-ever English edition of the influential Belgian Surrealist painter's literary output makes available for the first time to an Anglophone audience a selection of the artist's essays, letters, manifestos, interviews, and even prose poems—this latter genre being one which particularly appeals to Eric and me. (We're poets, too, and have brought our Poems While You Wait project to the MCA several times over the past few years.)

This book stands as an indispensable complement to Magritte's own paintings, a notable one of which is The Wonders of Nature

While this book of his writings does not seek to explain or interpret the artist’s work, it does offer new insights on how Magritte approached his canvases and how he hoped his audience might see them. For example, the brief prose poem, “Theatre Right in the Heart of Life,” reads in its entirety:

Doubtless it was a princess coming out of the wall, smiling, in the house surrounded by a magnificent sky. On the table were choice fruits, looking like birds. The lighting was comprehensible, despite a few unaccountable shadows and the lack of perspective beyond the open doors. The whole was dynamic thanks to the proportions.

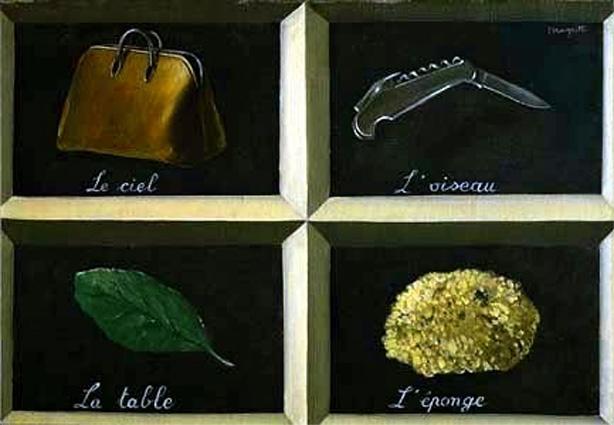

Now the princess is running, an amazon without vertigo, in the boundless fields searching for mysterious proofs. She uses up the thoughts and acts of an infinite crowd of people. She gets over poetic obstacles: suitcase, sky; penknife; leaf; sponge, sponge.

on Theatre Right in the Heart of Life

Here, fans of Magritte's painting will notice that many of the objects and items he chooses to include in this piece also appear in his various works, such as the penknife, which becomes a “bird” (l'oiseau) in La Clef des songes from 1927.

La clef des songes (The Interpretation of Dreams), 1927. Staatsgalerie Moderner Kunst, Munich, Germany

on R. M. has changed

And in his short, flash nonfiction piece “R. M. has Changed . . . ,” which dates from 1943, Magritte wrote a few lines to help inspire his dear friend, Marcel Mariën, to compose a preface for an exhibition of Magritte’s work at Galerie Dietreich:

R. M. has changed the use of painting. Here it is no longer a question of mere vision, sensitivity or any other explanation usually used in the art world. You can more or less find these things in R. M.’s paintings. But a curious point of view deprives words of their power to explain. We long to know, but we try and satisfy this longing in a joyous atmosphere and the light in R. M.’s pictures lends an unexpected charm to our efforts.

On R. M. has Changed

Ultimately, the poet Paul Nougé wrote the preface, but these lines of Magritte's own—and the book as a whole—serve as a strange and wonderful chance for a new generation of art fans to rediscover Magritte's work, just as The Wonders of Nature helps us rediscover the sea.