Making Black Lives Visible

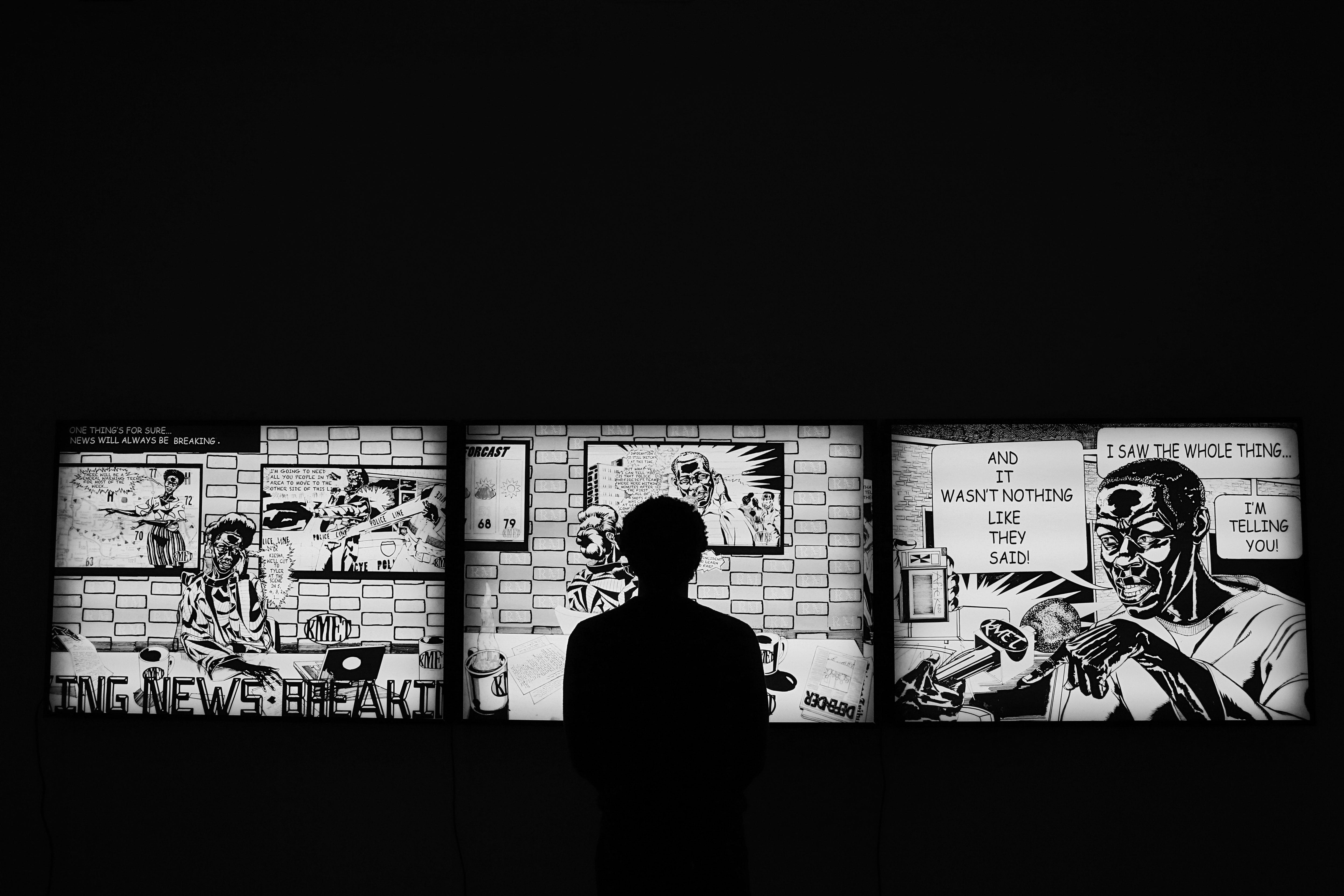

Installation view, Kerry James Marshall: Mastry, MCA Chicago, Apr 23–Sep 25, 2016

Photo: Jeremy Lawson Photography © MCA Chicagoblog intro

Whenever I step inside Kerry James Marshall’s MCA exhibition, I am struck by the beauty of the 81 works within it.

But what I respond to most isn't his sense of aesthetics. It is his sense of ethics, specifically his commitment to changing the way our society perceives black people.

Marshall learned at a young age, during trips to the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, that the history of art is, with few exceptions, a record of white artists and white subjects. “We tend to assume,” Marshall explained in a 2013 interview with art historian Tracy Zwick for Art in America, that “there is one history of America: the mythical, heroic narrative of an all-inclusive, grand project that had at its inception the goal of embracing differences and treating all as equal. If we allow ourselves to be lost in this mythology, we overlook the more disturbing, less humane dimensions of our history. We don't always learn that our nation's triumphs were at times achieved on the backs of other people.”

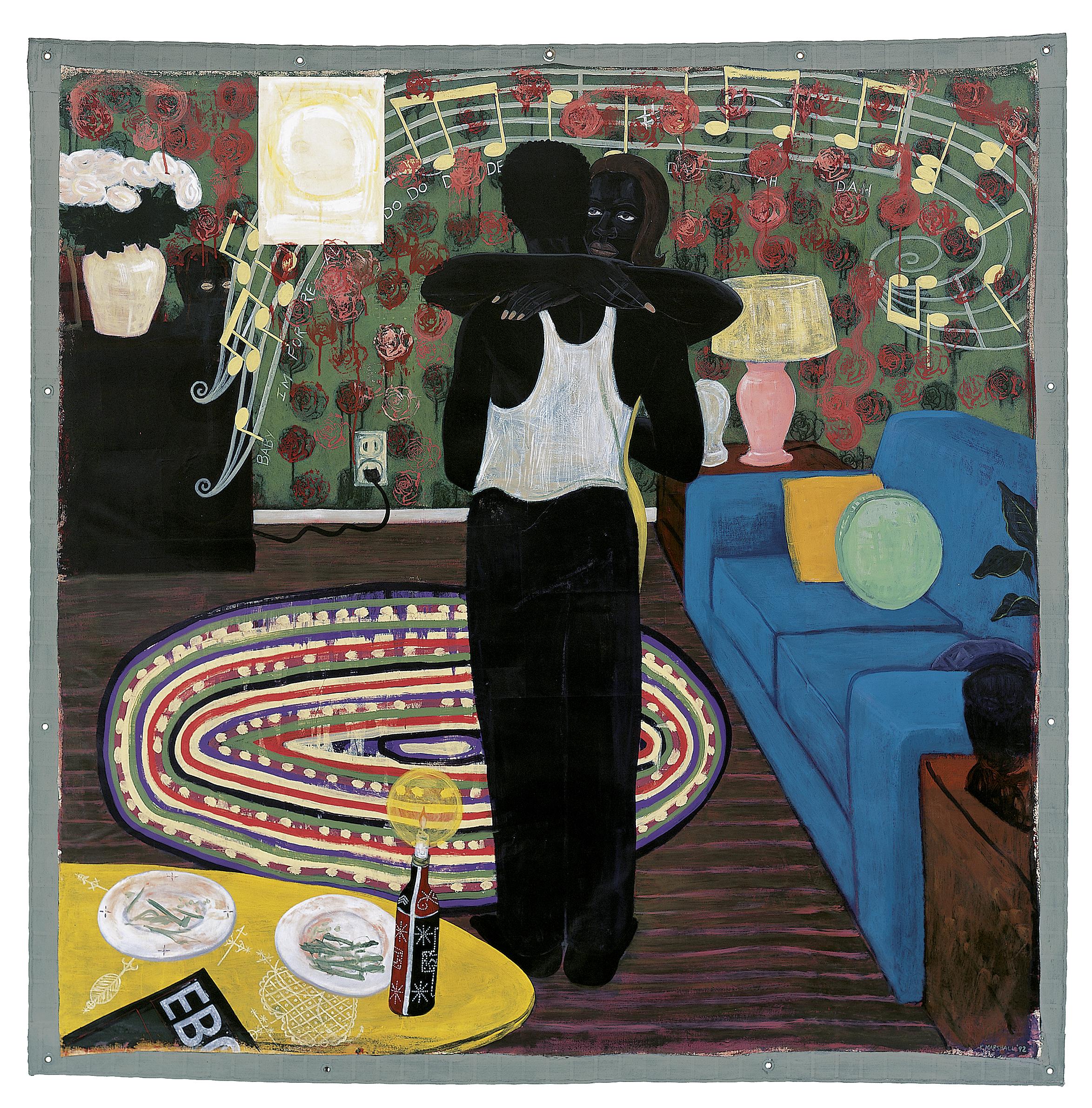

To prevent viewers from losing sight of this second narrative, Marshall has chosen to populate his paintings, drawings, and other artworks almost exclusively with black figures. Sometimes he portrays revolutionaries and activists whose acts of bravery are immortalized in the pages of history books. Nat Turner, Harriet Tubman, and Malcolm X all make appearances in his artworks. More often, though, he depicts ordinary black people engaged in more mundane activities—dancing in their living rooms, picnicking on their lawns, riding bikes around their neighborhoods.

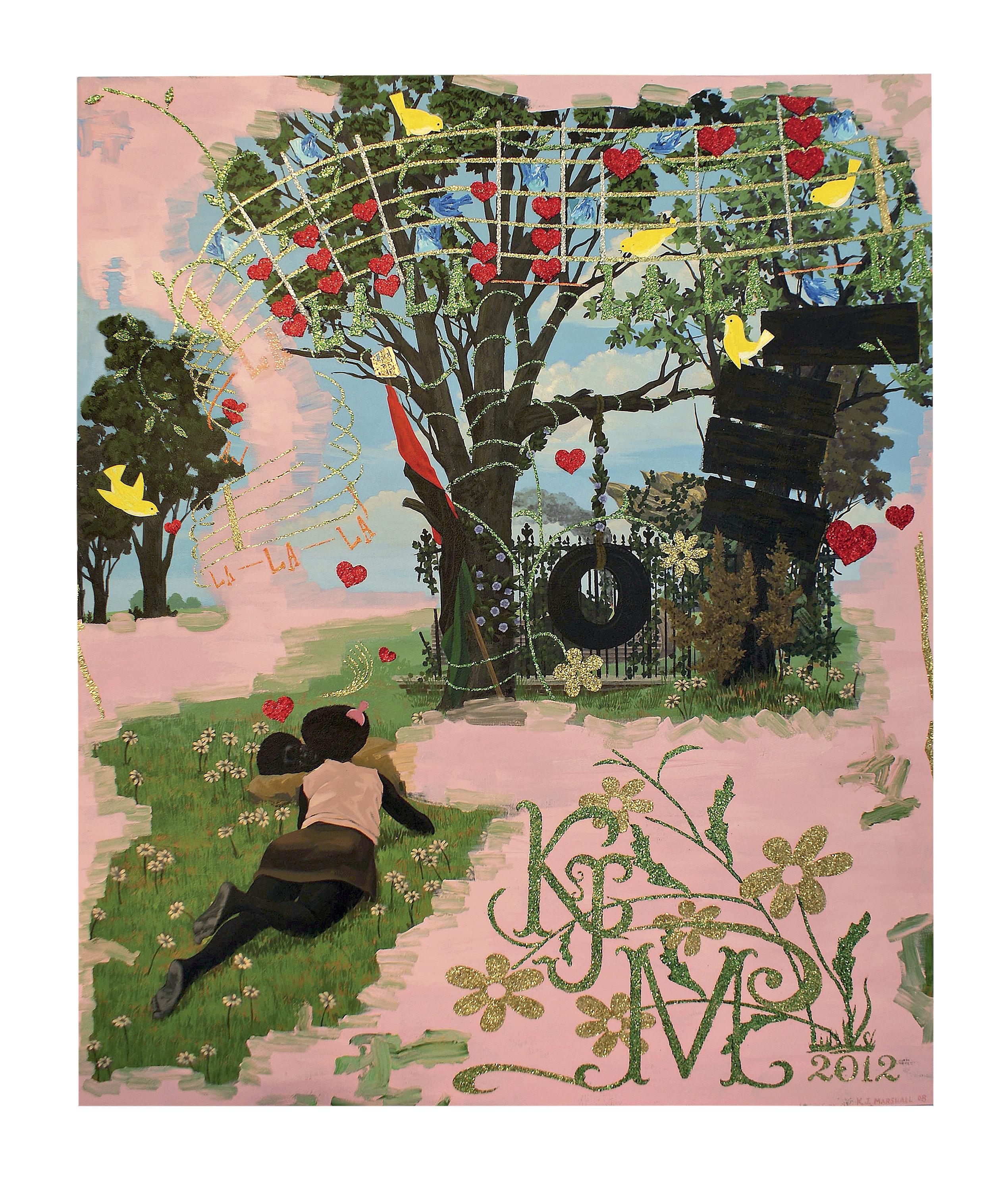

Kerry James Marshall, Untitled (Vignette) 2012

In his 2012 painting Untitled (Vignette), for example, he paints a young couple canoodling outside. The grass underneath the figures is a lush green, the sky above them a bright blue. And glitter-encrusted decorations—musical notes, chirping birds, and cartoon hearts—permeate the air around them. These ornamental flourishes evoke the aristocratic opulence and excess of the rococo period. We have no reason to assume that the figures in Untitled (Vignette) are particularly wealthy or powerful, though. Rather, Marshall seems to be suggesting that they are a perfectly ordinary black couple, and that their love alone is reason enough to warrant their inclusion in a massive painting, a major museum exhibition.

This idea is at the heart of Marshall's artistic mission. “I am trying to establish a phenomenal presence that is unequivocally black and beautiful,” Marshall writes in an essay that appears in his MCA exhibition catalogue. “It is my conviction that the most instrumental, insurgent painting for this moment must be of figures, and those figures most be black, unapologetically so.” His commitment to portraying the everyday ups and downs of black lives has always been admirable, but it has become even more noteworthy in recent months, in the wake of so much suffering and so much negative news coverage. For that reason, it is something that I think all of us, regardless of race, should strive to understand and appreciate.

Most of us are already aware that African Americans are underrepresented in our national media landscape. Black people make up a little more than 13 percent of the population, but they comprise a far smaller percentage of the characters that appear in film, television, and literature. The Cooperative Children's Book Center at the University of Wisconsin-Madison found, for example, that—of the roughly 3,500 children's books published between 2002 and 2014—only about five percent featured black protagonists. Worse still, only about three percent were actually written or illustrated by black people.

And when black people do receive media coverage they are often depicted negatively, cast either as criminals or victims, abusers or the abused. According to the 2015 News Accuracy Report Card issued by the activist organization Color of Change, news networks give the false impression, through the stories they choose to cover, that black people commit about 75% of the city's crimes. African Americans are overrepresented in stories about other societal ills as well: political scientist Bas van Doorn analyzed 474 magazine stories about poverty—printed between 1992 and 2010—and found that about half of them were accompanied by photographs of black people, even though only a quarter of the US population living below the poverty at the time was black.

These statistics would be disturbing even if they didn’t have larger social implications. But they do. The images we see affect the way we think and act. And the too-often negative images of black people that have flooded our news outlets and social media feeds in recent months are affecting us. They are fueling flames of intolerance, making it easier for police officers to shoot without thinking, for people to accuse Black Lives Matter activists of terrorism, for politicians to attack people of color at their campaign rallies.

This is why Marshall’s ongoing effort to populate art museums with richer, more representative depictions of black life is so important. When visitors walk through his MCA exhibition, they see girls huddled around a campfire in the rain, a grinning young man about to propose to his girlfriend, a couple admiring a sunset. In short, they see the full range of human experience—from ordinary to the extraordinary—and they see it represented entirely by black men, women, and children. In this regard, Marshall is reminding us, one work of art at a time, that the black experience encompasses so much more than what we typically see in the media, and that all of us should strive to look closer, to try harder to build a world for ourselves that is as rich and as inclusive as the one he has created for us.

Images

Kerry James Marshall, Campfire Girls, 1995. Acrylic and collage on canvas; 103 x 114 in. Collection of Dick and Gloria Anderson

Photo: E. G. Schempf

Installation view, Kerry James Marshall: Mastry, MCA Chicago, Apr 23–Sep 25, 2016

© MCA Chicago

Kerry James Marshall, Slow Dance, 1992–93. Mixed media and acrylic on canvas; 75 1/4 x 74 1/4 in. (191.1 x 188.6 cm). Lent by the David and Alfred Smart Museum of Art, The University of Chicago; Purchase, Smart Family Foundation Fund for Contemporary Art, and Paul and Miriam Kirkley Fund for Acquisitions

Photo © 2015 courtesy of The David and Alfred Smart Museum of Art, The University of Chicago

Installation view, Kerry James Marshall: Mastry MCA Chicago, April 23–September 25, 2016