Living the Conjured Life: Joe Shapiro

by Lynne Warren

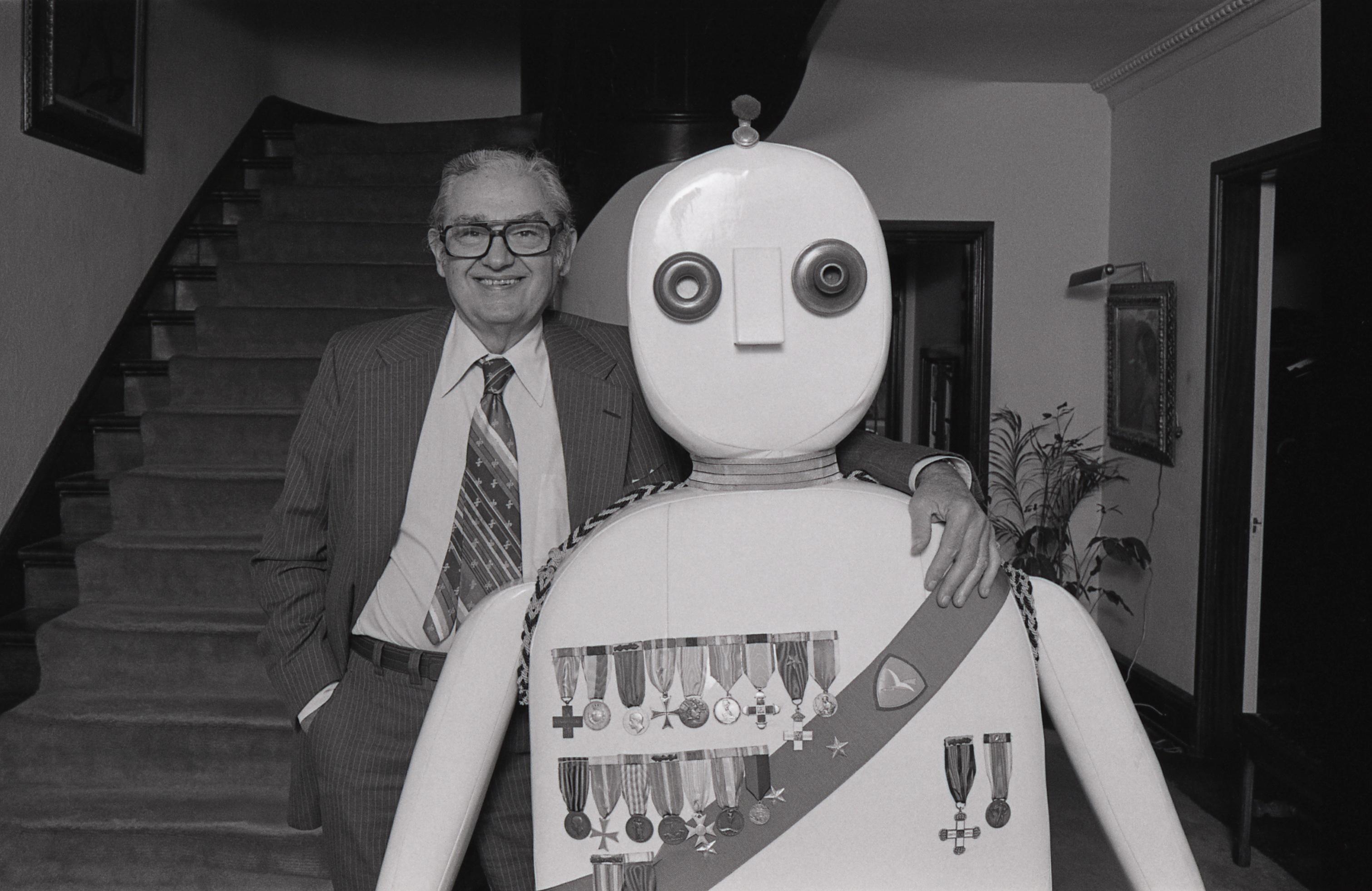

Joe Shapiro in his Oak Park home. Pictured with Enrico Baj, Punching General, 1969. Collection Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago, gift of Joseph and Jory Shapiro, 1992.49

Photo © MCA ChicagoBlog intro

One of the pleasures of mounting Surrealism: The Conjured Life is that it highlights the extraordinary generosity of the MCA's founding trustees. The one I knew the best, Joseph Randall Shapiro, was a generative force in the creation of the Museum of Contemporary Art in the 1960s. I wrote an appreciation of Joe, as everyone knew him, back in 2005, and have revised it for posting here.

on Shapiro’s books

In the early 2000s, I had the task—a labor of love, really—of sorting through Joseph Randall Shapiro’s library, donated to the MCA upon his death in 1996 at age 90+ (he was of a heritage—Russian Jew—and era where birthdates were often obscure).

His books were not fancy, fine editions. They are all fairly ordinary, the cloth covers and brittle, acidy paper of the commercial press predominated. Many were paperbacks. None were adorned with bookplates—a feature I have found in books from many collectors' libraries of that era—although many were signed as gifts from friends, including artists. A number featured pencil marks and notes in Joe's hand, especially the essays by Jung ("Psychology and Literature") and Hume ("Of the Standard of Taste"). I don't know what I was looking for when I picked up the book History of Art Criticism, by Lionello Venturi, published in 1936, its tattered dust jacket folded up and stuck between the final pages and the back cover. But rather than relegate it to the “book sale” pile, I brought it home and read it. This is what I found:

The opinion that in the nineteenth century there was not an art so great as in the preceding centuries is a stupid one…at least eight painters of the nineteenth century were of supreme greatness: Goya, Corot, Daumier, Manet, Renior, Cézanne, Seurat, Van Gogh. These are enough to give us assurance that art is not dead; that our aspirations, our ideals of yesterday have found their perfect pictorial expression. And they direct us to what is produced of authentic art at the present time. It is evident that so long as we refer to information of sources . . . without re-living them, without transforming them in our thought, without having introduced them to present life, there is no history but only chronicle.

The thought that there is “no history, only chronicle” without deep knowledge of and authentic reconsideration of the past is something I, as a long-time MCA curator, think about a lot. It is more than a little sad to me that today's viewers of Joe's donated works—seventeen of them on display in The Conjured Life, and many more in the collection—know very little about Joe himself. And I know Joe would agree that a chronicle is a perfectly fine thing, but a history makes life worth living. A chronicle would be a listing of all Joe's acquisitions and when he made them, how much they were worth, and how much they got at auction when he sold some of them because he thought his beloved wife Jory would certainly outlive him and needed to be taken care of (she passed a few years before he did). A history would include that Joe loved Jory more than anything. One of his proudest possessions was a portrait, done by an obscure local painter, of Jory when she was young. Joe would never fail to point it out when yet another first-time visitor was on “the tour.” He would challenge the viewer to identify the painting. There would be a panicked silence. This certainly wasn't a Delvaux or a Balthus, but what was it? “Renoir?” No. “Pissarro?” No. A sly, delighted smile would gradually spread across Joe's face as the visitor continued to sputter and squirm. “That's my girl,” he would say in his breathy, gentle voice, “That's Jory.”

Joe Shapiro in his Oak Park home. Pictured with René Magritte, The Wonders of Nature (Les merveilles de la nature), 1953. Collection Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago, gift of Joseph and Jory Shapiro, 1982.48

Photo © MCA Chicagoon Shapiro’s books, cont.

To handle his books was to be overwhelmed by memories of his Oak Park home, stuffed with Balthus, Cornell, Matta, Klee, Dali, Delvaux, Miro, Ernst, Magritte, Gorky, Seligmann, Marisol, Bacon, and many others, including many Chicago artists (Joe was one of the first to acquire the works of H. C. Westermann), most of which he donated to either the Art Institute of Chicago or the MCA. In fact, he donated much of his art collection during his lifetime, for he loved his artworks like children—an increasingly old-fashioned notion—and understood that the ultimate expression of that love was to send them off into the world where others could interact and form relationships with them. And like children, he gave his paintings and sculptures nicknames. For years the signature Magritte masterpiece of “men-fish” in the MCA's collection was called “Song of Love” rather than its proper name, The Wonders of Nature (Les merveilles de la nature), because Joe looked at the stony, cold figures as they crowded against one another and saw only love.

on Shapiro’s home

I loved and admired Joe's passion for life and art, and the obvious sustenance he drew from them. He was famous for opening his home to tours; I've gotten notes from those who have viewed The Conjured Life and remembered the time years ago when they had the privilege to see the Shapiro masterpieces that hung on every wall amidst well-worn modernist furniture (among the threadbare sofas could be found Barcelona chairs, a Noguchi coffee table). When the visitors arrived, Joe would stand by the Enrico Baj Punching General, draping his arm around it like the old friend it was, and smile and warmly greet everyone. Behind that amazing smile was a savvy businessman, who used his charm and powers of persuasion (he was a lawyer by training) to convince a “small band of conspirators,” as he called them, to fund his dream of a museum of contemporary art. Many of these individuals did not collect contemporary art, and some weren't art collectors at all, but he appealed to their civic-mindedness. “Chicago needs another great museum,” he would say, “Chicago is big enough and cosmopolitan enough to support a museum of contemporary art.” And although it wasn’t easy, of course he was right.

Installation view, Surrealism: The Conjured Life, MCA Chicago, Nov 21, 2015–Jun 5, 2016

Photo: Nathan Keay, © MCA Chicagoon Shapiro’s involvement with the museum

Joe loved to lunch with what he jokingly called “his harem,” curators and other museum people—mostly female of course—at those dreary sorts of middlebrow restaurants that sprang up in the 1950s and 1960s, such as The Homestead in Oak Park. Very few of these restaurants are around today and thus can exist in some sort of rosy glow of nostalgia. In reality these sorts of places were pretty awful, serving bland food in tacky settings. Of course it wasn’t the food that Joe enjoyed at these restaurants. It was the company and conversation that he craved, which were considerably more sustaining to him than the daily specials. Joe was an esthete who could converse on the highest levels about art, but he was also down-to-earth. He savored his role as a leading trustee and status as a legendary collector, but he was really tickled to author an advice column titled “Joe Sez” for a long-ago MCA staff newsletter. Here’s a taste:

Dear Joe: We are interested in the art of surrealism and would like an in-depth discussion on this subject from you.

Joe Sez: Surrealism was a way of life, a point of view, a liberation from the frozen stereotypes of conventions, morality, and outworn utilitarian ideas. Its aspiration was transmutation: “to transform the world, change life, remake human understanding.” Man must be viewed not as anatomy, but psychology; a tree not as lumber, but as growth; nature not as subdivided real estate, but as hallowed ground, ruled by demonic powers . . . .

And the “in-depth discussion” goes on for many pages.

Joe served as the MCA's president from the time it opened in October 1967 to 1973 and remained active on the board until the end of his life. His enthusiasm for art, especially surrealist art, lives on through the works of art he collected and generously donated, and is a palpable part of The Conjured Life.