Tous Ensemble!: The Art Ensemble of Chicago in Paris

Video

In 1969, the newly formed Art Ensemble of Chicago took up a residency in Paris at a fortuitous time—when the French underground was seeking inspiration in politicized forms of culture. Free jazz, with its pronounced connection to black nationalism and Afrocentrism, was celebrated among French counterculture critics as well as more mainstream French jazz fans as an authentic expression of the voice of the oppressed. The rich literary world of jazz criticism, including the underground monthly Actuel magazine, was critical in communicating this interpretation of free jazz to listeners and in distributing recordings of the Art Ensemble through the BYG Actuel label. Jazz had a long tradition in France, which had served as its second home since the 1930s, and a number of African American musicians had taken residency in Paris as it was seen as more racially inclusive since the days of the Harlem Renaissance. This made the city an obvious choice for Roscoe Mitchell's new combo, which left Chicago in search of new audiences and opportunities.

Besides the strong traditions of jazz, the Art Ensemble found a sizable French audience thanks to the cultural fallout from the events of May 1968, a series of worker and student protests, which briefly paralyzed the French state. While the alleged revolution that the protests represented never materialized, many hoped that by changing culture, society would follow. Audiences were attuned to politically engaged art, and free jazz represented that ideal in a manner that coincided with the desire for authenticity in culture. The very ideas that shaped the Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians (AACM) resonated among educated French audiences as indicative of a new form of politicized music that answered their hopes to find the combination of political engagement and cultural sophistication. George Lewis notes in his history of the AACM the high level of discourse that characterized the French response to free jazz. Eric Drott, however, observed that French audiences oversimplified the aesthetics of free jazz and that groups such as the Art Ensemble did not match those musical aspects touted in the French press despite critics' continued efforts to lump the group into a broad definition of the “new thing.”

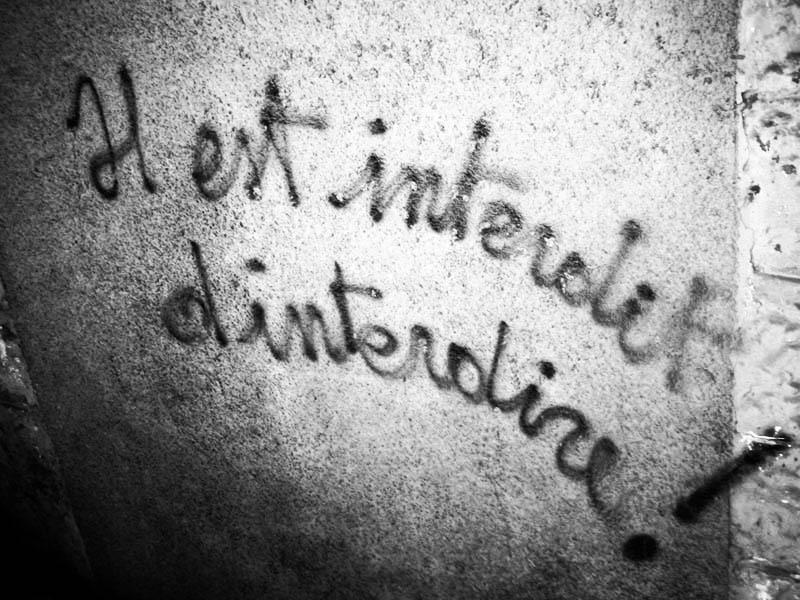

Situationist graffiti, France, 2006, with May 1968 slogan, Il est interdit d'interdire! (It is forbidden to forbid!)

This disconnection did not stop the French press from equivocating free jazz and black power and calling on French musicians to adopt the ideas of African Americans to transform French society. Some critics, such as Jean-Louis Comolli, had understood free jazz as a critique against global capitalism, echoing many of the Marxist ideals written on the walls of the Latin Quarter in May 1968.

Graffito in University of Lyon classroom, 1968

Others saw it as the expression of black revolutionary consciousness. In a sense, the embrace of free jazz was an effort to break the existent canons of jazz criticism in France; a political choice within an aesthetic one that had little to do with the actual ideas, music, or presence of the Art Ensemble.

Free jazz was also understood to be vital to transforming the existing musical culture in France, which failed to respond to the revolutionary events of 1968. In an effort to cement this attempt at an alliance, French pop groups performed alongside the Art Ensemble in theaters and most notably at the Actuel Festival during 1969. Some pop groups, such as Red Noise and Magma, made serious and sincere attempts to combine pop and jazz but for the most part these were limited in scope and often ended in frustration for both sides. Established French jazz musicians, for their part, also struggled to find their place within the free jazz community, especially given their sensitivity to accusations of minstrelsy and the association of free jazz with black consciousness.

Video

Ultimately, the Art Ensemble’s and the AACM’s politics were far more complex and nuanced than the French press presented and the call to adopt the ideas of the AACM sat uneasily with the latter’s fears of co-optation by broader audiences. The subtle nature of the Ensemble’s performances, which mixed traditional instrumentation and bricolage forms of percussion, were often lost on critics who celebrated the authentic nature of the group more than its stylistic and aesthetic innovations. A tenet of the AACM was the importance of reaching black communities. The paradox of coming to Paris for a residency to play to audiences that celebrated the black authenticity of the Art Ensemble was that these audiences were primarily white and middle class in composition. Despite the presence of marginalized Africans in Paris during the 1970s, jazz was understood as art music and embraced by students in the city centers more than the minority communities that lived in the suburbs, and the Ensemble’s residency in France ultimately petered out.

Video

Despite their failed attempt to generate a global audience (as Art Ensemble member Lester Bowie had hoped to find), the Art Ensemble’s presence did invigorate continental jazz, opening more interactions among contemporary cultural music, electronic music, and improvisational performances. It also expanded the champions of free jazz and introduced its ideas (albeit often in over-romanticized ways) to new listeners who would in turn integrate the “new thing” into their understanding of jazz. And while the intentions of the AACM were often lost on French audiences, the sounds of the Art Ensemble transfixed them.