In Conversation: Lynne Warren with Rafael Ferrer

Installation view, Rafael Ferrer: Tierra del Fuego, MCA Chicago, December 16, 1972–January 28, 1973

Photo © MCA Chicago © Rafael Ferrer/Licensed by VAGA, New YorkAbout

You will find a condensed version of this interview between Curator Lynne Warren and artist Rafael Ferrer in the current MCA Members' Magazine. Enjoy additional insights and anecdotes in this extended interview with the artist before MCA DNA: Rafael Ferrer opens this weekend on September 19.

About

Lynne Warren: How was the Tierra del Fuego exhibition, which featured paper-bag paintings, found-object constructions, altered maps, and invented flags—among other items—a turning point for you?

Rafael Ferrer: The key work that preceded all the so-called process works was the Three Leaf Pieces [wherein Ferrer did guerilla installations using autumn leaves in three contemporary art sties in Manhattan]. The reaction I perceived at that time from colleagues and tastemakers was that my work was excessive. I come from a culture where purity, denial, and guilt are not the driving forces. Mine is a place of improvisation, wit, and invention.

I found a map store in Philadelphia that sold aeronautical navigation charts with the whole world in quadrants. I bought the areas of the globe that resonated with tales, history, memories that intrigued me. Thus, Tierra del Fuego and the South Pole started the avalanche. Like melting ice, the maps began a warming of sterile dogma, mocking critical idiocy, making art with my hands rather than from arcane philosophical tenets. My earliest motivations leading to a desire to make art came from the excitement and admiration I perceived from the works of early 20th-century artists. The Dadaists—with their irreverence and black humor—were important, as were the developments of their influence in New York City in the early 1950s. Assemblage and Happenings became significant, as did the works of Robert Rauschenberg and Claes Oldenburg. As my work accumulated, paper bag faces and maps were objects which in turn led to flags, hybrid constructions made of boat parts and oars, ironing boards with metal hats, and then to the kayaks made of corrugated steel and rawhide.

This became a museum—my museum or MUSEO. It was my natural history, and the MCA allowed this museum’s incarnation to occur, a most generous and welcome act by Steve Prokopoff, the then-director.

Rafael Ferrer, Kayak #2: Norte, 1972. Corrugated steel, bone, rawhide, fur, wood, knife, string, hair, siding, and paint; 26 x 119 5/8 x 16 in. (66 x 303.8 x 40.6 cm). Collection Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago, gift of MCA Collectors Group, 1976.17

Photo: Nathan Keay, © MCA Chicago © Rafael Ferrer/Licensed by VAGA, New YorkAbout

LW: Two major works from Tierra del Fuego will be featured in the MCA DNA presentation: A Flag for the Straits of Magellan and Kayak \#2: Norte. You grew up in Puerto Rico and, for me, these works evoke great realms carved out by your imagination and experience, allowing me to travel to vivid places through your artworks. Did you ever actually visit the Tierra del Fuego islands, or are they a proxy for your experience of the island of Puerto Rico?

RF: I went to Syracuse University for two years. During that time I worked as a musician—playing drums—and formed a Latin Jazz group that played in a local nightclub. I enrolled at the University of Puerto Rico in the fall of 1953, and it was there that I met and studied with Eugenio Fernandez Granell, a surrealist painter and writer. His influence was manifested in long conversations, books that he suggested, and anecdotes involving his friendship with the ample panoply of surrealist poets and painters. This led to a trip to Europe in the summer of 1954. I spent that summer in Paris, where I met up with Granell. Through him I met André Breton and Benjamin Peret and joined their weekly meetings in cafés. I attended openings, most memorably one of the works of Pablo Picasso from collections in Russian museums. With Granell I visited the studio of Wifredo Lam. This was significant because Lam, being Cuban, enabled me to speak about Afro-Cuban music, my knowledge of it, and its power.

This answer suggests that my choices are tied to my imagination. No doubt that having been born on an island in the Caribbean, which became a colony of the United States in 1898 and is now the oldest colony in the world, is part of who I am. My art is personal, which means that it responds to my nervous system and is not guided by any overarching philosophy. I do believe that democracy and capitalism have reached a point of incompatibility. Predatory capitalism devours systems, converting them into entertainment, which is highly lucrative. Art faces this dilemma.

LW: Another major work featured in the exhibition is also a gift from your long-time patrons Earl and Betsy Millard, namely the extraordinary cycle of paintings Cien Anos de Soledad (One Hundred Years of Solitude) of 1982. You were commissioned by the Limited Editions club to illustrate a deluxe edition of Gabriel Garcia Márquez's novel and created a cycle of 13 oils painted in your characteristic direct, island-influenced style. This novel was very important to you, I understand. How did you feel when you were asked to do paintings based on such a marvelous work of literature?

RF: My initial response to the invitation was tremendous excitement. I had read the novel in Spanish and English in 1970. I also had to face the issue of illustration, something that I had always criticized. Words cannot be equated with images. Movies made from novels are generally awful because of this impossibility. Garcia Márquez never allowed the novel to be made into a movie. I tried to create images which would not be tied down to a specific narrative in order to allow visual elements that could simply be cryptic. I have no idea what “island-influenced style” means. There are some tiny Goyas, barely discernible, as well as a thousand examples [of visual elements] from every century. Facts: the size of the canvas is 18 by 24 inches; and there are Seventeen Aurelianos. The primitive canard? Really?

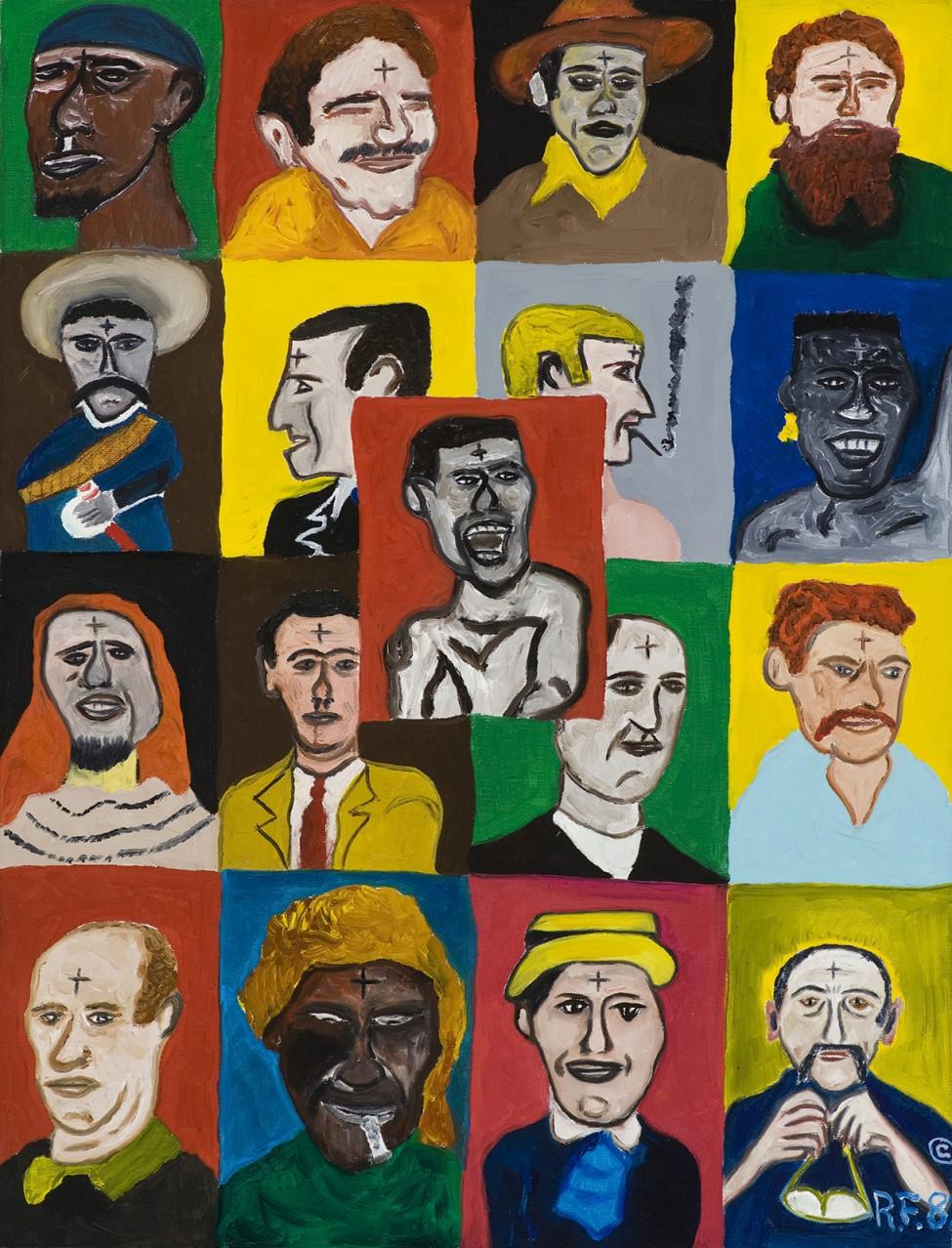

Rafael Ferrer, Los Diecisiete Aurelianos (The Seventeen Aurelianos), 1982. Oil on canvas; 21 1/2 x 16 7/16 in. (54.6 x 41.7 cm). Collection Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago, gift of Earl and Betsy Millard, 1991.46.7

© Rafael Ferrer/Licensed by VAGA, New YorkAbout

LW: I notice a lot of the faces in one of the “Solitude” cycles—Los Diecisiete Aurelianos {bio: (The Seventeen Aurelianos)—look familiar; you've mentioned some are portraits of artists and others who are important to you. I see Grace Jones in one, and a self-portrait in another, also Carl Andre and Alex Katz and is that Jackson Pollock with the bald pate and red hair? What was your impetus to use real visages to represent the doomed sons of Colonel Aureliano Buendia?

RF:Los Diecisiete Aurelianos was a real joy. In the novel all 17 of them had a cross on their forehead. They were all different races, colors, and sizes, were dispersed all over the world, and they all died on the same day. Sorry dear—Grace Jones is not an Aureliano; that is Chano Pozo the legendary Cuban conga drummer. Pollock and Carl Andre: not there. I will tell you who is there [in the picture]. I do recall Donald Judd, Robert Morris, Alex Katz, Emiliano Zapata, and, of course, Gabriel Garcia Marquez. And the last one is me. The impetus for doing this is the manic, mischievous inventiveness that permeates the novel and is intrinsic to the region. Macondo is really a Caribbean village with all the idiosyncrasies known to all of us who were born in this basin. Aracataca, Garcia Marquez's birthplace is near the coast.

LW: Music has been an important part of your life and you were a professional drummer involved in the Afro-Cuban music scene in the 1950s before you began to make visual artworks. The three-work cycle Elegia para un Amigo (Rafael Cortijo Verdejo, 1928–1982)} (Elegy for a friend [Rafael Cortijo Verdejo, 1928–1982]), 1983, I find particularly moving. Can you tell me a little about your friendship with Cortijo, who was one of the Caribbean's most successful artists of the 1950s and 1960s?

RF: As a percussionist, I had gigs with different groups in Puerto Rico. I happened one day to play with a large orchestra in which Rafael Cortijo was the conga drummer, while I played the timbales. We spent our breaks talking, and from that evening on we became friends. Musicians hang out with musicians; you practice, talk, listen, and learn. Rafael was an extraordinary individual. Elegant, generous, he had a quality which I always imagined came from African royalty. I would go to his house and meet his older sister and brother. He would come to my house, where I still lived with my mother. One day he said that he wanted to introduce me to a friend, who worked in construction as a brick layer, that he felt was a terrific singer and was going to join his group. This person was Ismael Rivera, who became one of my greatest friends from that unforgettable period: the Golden Age of our music in Puerto Rico and New York City. In Manhattan it was the heyday of the Palladium Ballroom, where the greatest bands from Cuba, New York, and Puerto Rico played. Birdland, a block away, was where Charlie Parker, Thelonious Monk, Dizzy Gillespie, and all the greats of jazz played. Musicians from these two extraordinary music idioms listened to each other, thus enriching music and creating an excitement unparalleled anywhere else.

When Rafael Cortijo died, I was not told about it until after his burial; thus, my elegy came from my grief, the images motivated by the photographs in the papers. When Ismael Rivera died, Francoise and I flew to San Juan, arriving after midnight, and friends took us to the Institute of Puerto Rican Culture, where his body was seen by multitudes of fans. The next day his body was taken to the Public Housing Project in the neighborhood from where Cortijo and Ismael Rivera came. It was an amazing experience, though nothing compared to the funeral the next day. Francoise and I arrived as the coffin was being brought out to the multitudes chanting, “A pie! A pie!,” meaning the crowd wished to carry the coffin on foot all the way to the cemetery, which was a very long distance away. My friends motioned for me to join the first group of pallbearers carrying the incredibly heavy coffin under a blazing sun. Thousands lined the streets as we all chanted songs we knew from our lives in music. Dripping wet with sweat, Francoise holding on to my belt so she wouldn't get lost in the crowd, I finally had to allow others eager to take my place to continue and share task. The cortege continued slowly along the route to the cemetery where Ismael would be buried next to Cortijo.

LW: Although you never lived in Chicago, you had some deep friendships here, especially among the Hairy Who and other artists around the Phyllis Kind Gallery, where you once showed. Can you tell us about your experience of Chicago's “Imagist” artists?

RF:Tierra del Fuego at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Chicago opened up a world that was in sharp contrast to the art scene in New York City, and clarified for me the direction my work was taking me. I met Phyllis Kind before the museum opening. She became my first dealer in the United States. An extraordinary individual, Phyllis received us with open arms, she introduced us to her artists and in a very short period of time, these artists in turn introduced us to their friends, to collectors and to a group of luminaries who made up the vibrant scene in Chicago at that time. The art and artists of Chicago had created an art world independent from the exclusivity and categorizing prevalent in New York. Roger Brown was our closest friend in the city. Francoise and I stayed with Roger and his partner George Veronda on our frequent visits to Chicago. We would see Roger in New York City on his visits to exhibit with Phyllis Kind in her Soho gallery. Our friendship lasted until Roger's untimely death.