The Permanence of Memory

by Ana Nieves

Doris Salcedo, Plegaria Muda, 2008–10, Wood, concrete, earth, and grass, 166 parts, each: 64 5/8 x 84 1/2 x 24 in. (164 x 214 x 61 cm), Overall dimensions variable, Installation view, CAM–Fundação, Calouste Gulbenkian, Lisbon, 2011, Inhotim Collection, Brazil

Photo: Patrizia TocciLooking at Doris Salcedo's art you can sense that it's informed by a deep history, even if you know almost nothing of the artist herself. We wanted to dive into that history more, so we asked Ana Nieves, an art historian who specializes in art of the ancient Americas and teaches Latin American art at Northeastern Illinois University, to share her perspective and insights into the history and artworks in Salcedo’s retrospective.

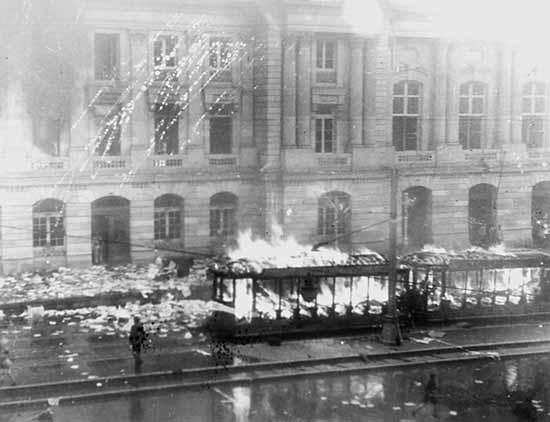

Bogotá, April 9, 1948: Three gunshots echoed through the city leaving the target, influential leader of Colombia’s Liberal Party and presidential candidate Jorge Eliécer Gaitán, dead. Built on years of social unrest and the escalating tensions between Liberals and Conservatives, this single event helped to alter the course of Colombian history forever.

Immediately after Gaitán's death, an angry mob lynched the man suspected of his murder and abandoned his corpse in front of Colombia's Presidential Palace. The riots that followed—the Bogotazo—marked the beginning of La Violencia in Colombia, a period of civil war that claimed approximately 200,000 lives through the 1950s. During La Violencia, Conservatives controlled the army and supported paramilitary forces while Liberals formed guerrilla groups in Colombia's rural areas. In the 1960s new left-wing guerrilla groups formed as a result of the conflict between these factions and still affect Colombia to this day. Civilians were caught in the middle, primarily the rural poor, and were often the witnesses and victims of violent acts. The illegal drug trade in the 1980s, ongoing political corruption, accusations of human rights violations on the part of the military forces, and an increase in violent crime have complicated matters considerably, making any hopes for a peaceful future seem unattainable at times. Since 1958, the approximate year La Violencia ended, Colombia's internal conflicts have claimed the lives of an additional 220,000 people. According to the Red Cross, there have been more than 92,000 reports of disappearances in Colombia in the last 50 years, and of that, approximately 68,000 people are still missing.

El Bogotazo, 1948

This incredibly violent history is at the heart of Colombian artist Doris Salcedo’s work. Developed from the viewpoint of the survivors, her works focus on mourning; the lingering, profound pain caused by a disappearance or a sudden death: the lack of closure, the desperate need to cling to hope, the unending questions, and the sense of emptiness. In referencing this sudden absence of a loved one, Salcedo often incorporates actions and objects that suggest wakes, such as the lighting of candles or the use of flowers. In a way, this language of loss is universal and Salcedo is not alone in presenting absence.

While walking through the exhibition Doris Salcedo, I was reminded of the work of Argentine artist Fernando Traverso, who also addresses forced disappearances. In 2001, Traverso began stenciling large images of bicycles across the city of Rosario, Argentina, ending only after he reached 350—the number of citizens who disappeared in Rosario during Argentina's Dirty War in the late 1970s. As a common form of travel used by members of the resistance in Argentina, for many, an abandoned bicycle could only mean that the person was no longer around to claim it; that person had disappeared. By representing an object to which these individuals were directly connected, they serve as memorials. Often painted in the location the bicycle was abandoned, these haunting, ghost-like images permanently alter the location, forever fusing the person to the place, leaving a visible scar.

Fernando Traverso, work from 350, urban intervention, 2001–2004

Rather than using representational images as a memorial, Doris Salcedo employs actual objects, with a clear physical presence that cannot be avoided. The large pieces of furniture, used in many of her installations, fill up large portions of a room, often limiting the visitor’s ability to move freely around a space. Her works are also often fragmented. By taking these objects apart and reassembling them as well as adding other materials, they cannot be used again, at least not in the same way. They remain forever changed, just like those individuals who are left to mourn.

Installation view, Doris Salcedo, MCA Chicago, February 21–May 24, 2015

Photo: Nathan Keay © MCA ChicagoDespite the heavy subject at hand in Salcedo’s works, they are inherently beautiful, as subjective as that term may be. There is a tactile quality to a lot of the work achieved through different materials and contrasting textures; there is a sense of repetition and harmony; and there is an admirable sense of meticulous detail in the techniques used to assemble these works.

Installation view, Doris Salcedo, MCA Chicago, February 21–May 24, 2015

© MCA ChicagoThere is also an undeniable sense of human presence in the objects Salcedo chooses for her installations that goes beyond their obvious utilitarian function and this is sometimes suggested only in fragmentary form. Hair, bones, and clothing are clearly part of some of the pieces if you look closely. In Unland: the orphan’s tunic, Unland: irreversible witness, and Unland: audible in the mouth, Salcedo joins parts from different tables to create a complete unit, but she did not try to hide the juncture between them, making them appear fragile, broken, and scarred. The artist then sewed human hair and raw silk through these tables, giving them a delicate, skin-like surface that makes them almost anthropomorphic. To see these details in Salcedo's work, however, it is necessary to look so closely that the larger object and its practical function can no longer be seen.

Doris Salcedo, Unland: the orphan’s tunic (detail), 1997. Wooden tables, silk, human hair, and thread. 31 1/2 x 96 1/2 x 38 1/2 in. (80 x 245 x 98 cm). “la Caixa” Contemporary Art Collection

Photo: Nathan Keay © MCA ChicagoWhile many of her works are a reaction to particular events, most works lack any specific reference to a particular place or time within them. In a way, they become more general presentations of human suffering caused by a profound sense of absence, reflecting the experience of loss for anyone at any time. And yet, her pieces always reveal a sense of hope and optimism. Plegaria Muda (“silent prayer”), for example, is an installation that limits and redirects the visitor's movements across the space, much like a maze—transforming the viewer into a participant rather than a witness. I found myself walking back and forth through the work instead of straight across the gallery, an action that seems to be at once directionless, confusing, and meditative.

Doris Salcedo, Plegaria Muda (detail), 2008–10. Wood, concrete, earth, and grass. 166 parts, each: 64 5/8 x 84 1/2 x 24 in. (164 x 214 x 61 cm). Overall dimensions variable. Installation view, Doris Salcedo, MCA Chicago. Inhotim Collection, Brazil

Photo: Nathan Keay © MCA ChicagoThe individual blocks that define the space of Plegaria Muda consist of two tables placed one on top of the other, with the uppermost table placed upside down and a layer of earth between the two. Tiny and delicate blades of grass grow through the wooden planks of the uppermost table, a reminder of life prevailing, according to the artist. At the same time, however, the powerful beauty of nature in relation to man-made objects can also become a reminder of death.

Frederick Catherwood, Castle at Tuloom, 1844

As with the nineteenth-century illustrations of Mesoamerican sites by Frederick Catherwood, where ancient structures are covered by foliage, we are aware that long after we are gone, nature will once again reclaim the land. When we look at Plegaria Muda, we are left to wonder what happened to those who once used these tables. We know that typically we turn tables and chairs upside down when we no longer need them. We are aware of the passage of time due to the presence of plants on the furniture. And we know that as time goes by and plants continue to grow on and around an object, there may be a point in which we may not be able to see the object anymore. But this is also the way memory works. With time, we bury things. But they are still there, underneath, and deep down we may not want to forget after all.

Although Salcedo and Traverso address violent acts, their works do not dwell on the events themselves, but rather on commemorating the victims and those that were forever changed by these acts. The violent episodes in Colombia’s history cannot be changed, but Salcedo’s installations serve as a reminder that the lives of those affected were human lives, much like ours.