Interview with Sergio Clavijo

Sergio Clavijo

Photo: Abraham Ritchie, © MCA ChicagoA great deal of effort goes into the seamless presentation of Doris Salcedo's works and behind those installations are highly trained professionals who watch every nuance of production and installation. Before Doris Salcedo opens on February 21, we sat down with Sergio Clavijo, one of Doris Salcedo's studio partners, to discuss the process and challenges of installing her works, his time in Chicago, and more.

Interview

MCA: Where are you from?

Sergio Clavijo: I am Colombian, but I live in Montreal, Canada.

MCA: How did you end up in Canada?

SC: My family. I am married to a Canadian, and now I have two sons who were born there. Well, one is born, but the other will be here in April.

MCA: Oh congratulations! That's wonderful!

How long have you been in Chicago?

SC: I've been here for three weeks now.

MCA: How long have you been working for Doris Salcedo?

SC: Since 2001. I worked with her for 10 years, then stopped to study, then I went back to [Doris's] studio, and then I moved to Montreal less than five years ago. I've been involved with the works but not with the studio production in Bogotá.

MCA: What did you study during the break from the studio?

SC: I studied architecture; I earned a master's degree in architecture. Even today my work is in architecture.

Doris Salcedo. Untitled, 2003. 1,550 wooden chairs. Approx. 33 x 20 x 20 ft. (10.1 x 6.1 x 6.1 m). Ephemeral public project, 8th International Istanbul Biennial, Istanbul, 2003

Photo: Muammer YanmazMCA: What did you work on today?

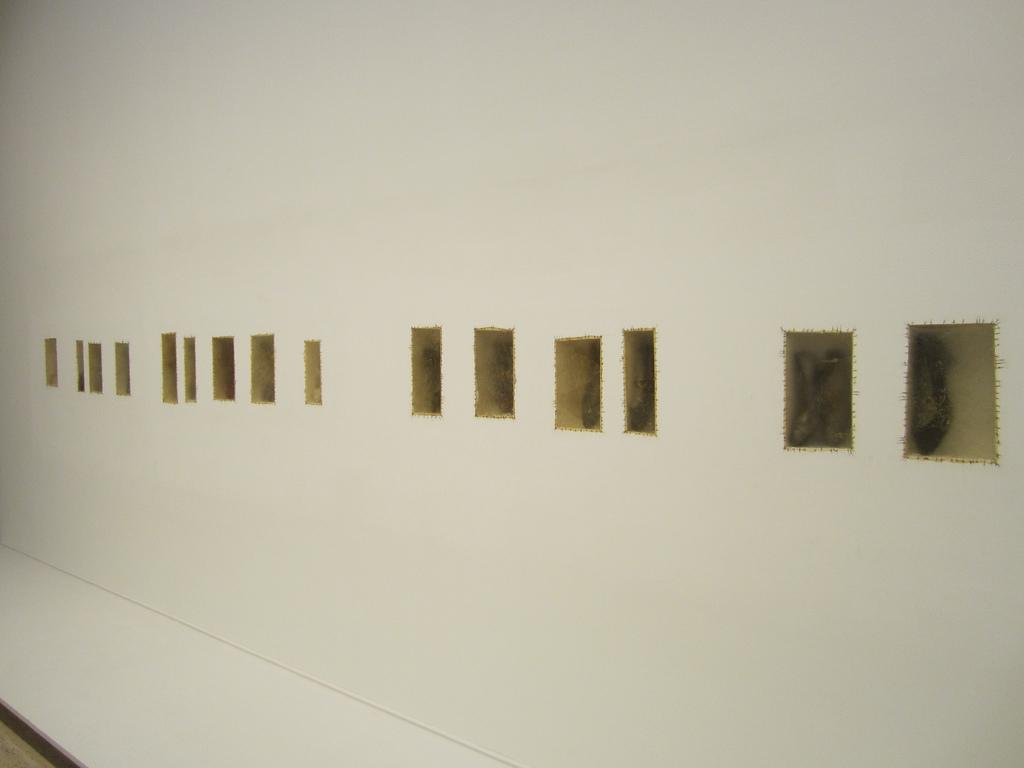

SC: I've been working on the installation of Atrabiliarios, and the overall setup of the room. We've been finalizing bringing the work into the walls, which is a big part of that installation. Putting them together with the actual wall itself is fairly complicated to set up so that it is flush with the existing wall. That's the struggle for today.

Doris Salcedo. Atrabiliarios, 1992–97. Shoes, drywall, paint, wood, animal fiber, and surgical thread. 43 niches and 40 boxes, overall dimensions variable. Installation view, Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney. Mervyn Horton Bequest Fund 1997, Art Gallery of NSW collection

© Doris SalcedoMCA: That's almost what we were going to ask you next. What is the most difficult piece you've worked on and what makes it difficult?

SC: That's a hard question to answer because there is a challenge, an extreme challenge, in each of Doris's works. Nonetheless, it's a challenge that's [overcome] through the talent of several people; there's not one mastermind here. There's Doris who directs and creates a concept, but then anything you see happening in terms of structure, installation, or design of crates or packages is [a product] of the many people who are involved. They are part of a studio and they are involved. They're not consultants. All the guys from the studio that are here have experience in these challenges. I think every one of them would answer very differently about what is the most challenging, but most likely their answer would be “what is to become,” that is, what they're working on installing right now is the most challenging. It's very hard to think of a more complicated thing after installing the most complicated thing you've ever done!

MCA: On a related note, what's the hardest thing to do in your job? Whether it's physical, personal, or even the emotional weight of the artwork.

SC: The hardest thing is to get people involved, the other workers. Meaning that there are professionals attached to each exhibition venue, like drivers, electricians, lighting technicians, even security. When you have worked on a piece of art you have a certain sensibility towards certain aspects of the piece. Not in conservation, but in terms of the piece itself. There's an extreme care and professionalism at a museum, and especially here at the MCA, but somehow you want more. That's very difficult because people are doing their jobs properly and correctly but you say, “No, no, you can make that drywall more flat if you put a shim in there.” So we ask for a shim. It doesn't follow the logic of a schedule, it doesn't follow the logic of building codes, but it's part of this difficulty to [make it perfect]. . . . The MCA crew has shown me their equipment and their process. They open up and tell me the way they do the work normally. By sharing this information we're able to work together to get the best result, for instance, “if you do two coats of that we might be able to get a better result,” and that kind of collaboration is happening. There's no planning for this kind of work, there are no instructions. It's in the interaction.

MCA: Since you'll be here for a while longer, is there anything you want to do while you're in Chicago?

SC: I want to get the installation done on time! But I'm also very interested in the architecture of Chicago.

The skyscrapers but also the Prairie-style residences, the Frank Lloyd Wright buildings, the [Louis] Sullivan's, and also the Mies van der Rohe work that's here. It's all very valuable. If there's a chance, some of the studio people here would like to try to go to the [Frank Lloyd Wright–designed] S. C. Johnson building in Racine, Wisconsin.