Notes from Rapid Pulse 2014

MCA Curatorial Assistant and Rapid Pulse cocurator Steven L. Bridges reflects on the third annual Rapid Pulse International Performance Festival, which took place this past June, and the personal and professional impact it has had on him.

Alison Crocetta and Peter Reese

Photo: Emerson Sigmanon the founding of rapid pulse

In the fall of 2011, Chicago-based artist Joseph Ravens—founder/director of Defibrillator Gallery—asked me to join him, then-graduate student Giana Gambino, and Chicago-based artist Julie Laffin in establishing a performance art festival in Chicago. At the time, performance art remained somewhat under-recognized within the greater arts ecology of the city. So Ravens, Gambino, Laffin, and I set out to create a more visible platform for groundbreaking performance work. That idea spawned the Rapid Pulse International Performance Festival.

Highlighted below are a selection of artists who I think reflect the uncategorizable nature of performance art practices. While some of these works may be disturbing to some (and, frankly, that is part of their conceptual conceit, as they engage with difficult subject matter), others explore how movement, play, and the somatic experience (i.e. the experience of and through the body) open up new and different paths for the production of knowledge and subjective understanding.

Michal Samama, What am I paying you for?

Chicago-based artist Michal Samama's performance took place inside the context of the gallery and involved only a plastic woven bag, the clothes she wore that day, and her body. As the title subtly implies, the underlying tone of the piece was antagonistic. The bag is one that is often used by immigrants and migrants, and its presence offered insight into the social classification of the performer. Samama entered the space nude with the bag balanced precariously atop her head. For the next 30 minutes, she moved deliberately throughout the space, drawing attention to and exploring the relationship of the bag to her body—whether as an oppressive weight, or an object of affection. To complete the performance, the artist unzipped the bag, took out its contents (her clothes) and dressed—slowly, methodically—in front of the audience. Samama is highly regarded for her work with the body, investigating its physical qualities and limitations. In this performance the body also became an object, along with and akin to the bag, raising questions about the objectification of the body—specifically the female body—and its (de)valuation in a capitalist, global society.

Carlos Martiel, Simiente

Cuban artist Carlos Martiel's performance also addressed the movement of bodies, though in a much more direct and politically charged way. His work focused on the suffering, both physical and psychological, that immigrants often face. For the piece, he invited Chicago-area immigrants to donate blood, temporarily transforming the gallery into a blood bank on the night before the launch of the festival. Martiel chose blood as his medium in part because it is an extremely affective material, one that most people have a strong aversion to, in spite of its vital importance. On the opening night, Martiel created a <em>tableau vivantem, lying naked on the floor of the gallery in a pool of the collected blood, his body flexed and tense, trembling. It was a difficult sight to take in—the experience raw and challenging to the viewer—but deeply moving nonetheless, especially to those who donated their blood and felt a sense of shared experience, of political and social status, with their fellow participants.

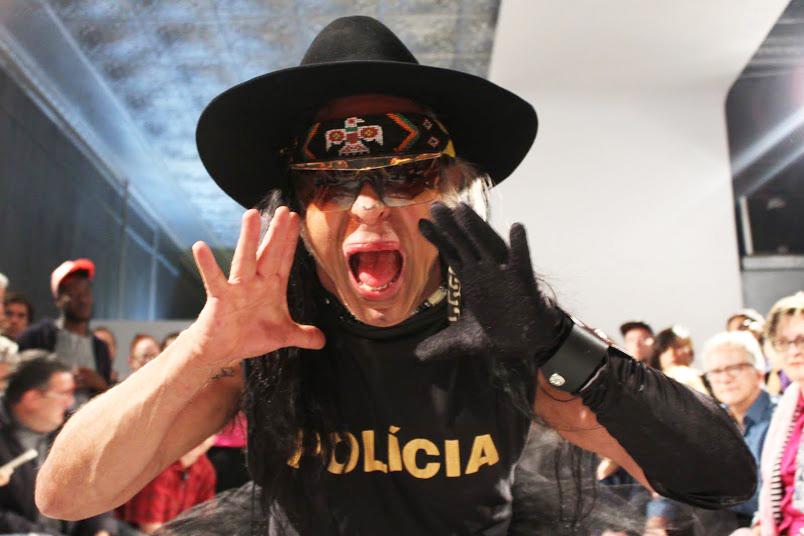

La Pocha Nostra

Founded by Guillermo Gómez Peña and Roberto Sifuentes, among others, La Pocha Nostra comprises an ever-evolving roster of artists. The performance for RP14 was at times pedagogical in nature, at times carnivalesque, and focused on creating images for mass consumption and distribution. To this end, Peña would halt the performance and invite audience members to take photos and upload them to social media sites, calling on them to “send these images all over the . . . world.” Throughout the performance, Peña also gave instructions to the other performers—Roberto Sifuentes and Erica Mott—along with the audience members, all the while developing a kind of meta-critique of the live performance as it unfolded in real time. At various moments there was a skinned goat draped across the back of a performer; the likeness of a Madonna covered in roses with milk pouring down her bosom; a boxing match; and a prop gun offered to audience members to pose with, held to Peña's body and head. Ultimately, the piece created a critical space around which all things performance were thrown into question, and in which moments of profanity mixed with references to the sacred.

Alastair MacLennan, One Four Six

The work of Alastair MacLennan—a member of the notorious avant-garde performance collective Black Market International—was meditative in nature, engaged as it was in unknown rituality. He embarked on a process that was very much experimental, improvised and momentary. Whereas La Pocha Nostra dissected performance through a series of loosely choreographed gestures, MacLennan created an impression of genuine, unscripted openness. The artist requested a seemingly random series of objects—fresh fish heads, an orange, a green apple, two buckets of water, ticker tape, a bundle of sticks, and so forth—which he arranged in a turnabout down the block from the gallery. As audience members gathered around him, he removed his shoes and blindfolded himself, relying entirely on his other senses to enact an open-ended process, punctuated at times with specific actions, like the pouring of a bucket of water containing fish heads and fruit over his head. A number of random passersby also encountered the piece, intrigued or bewildered by MacLennan's actions. Perhaps they assumed the rest of the audience members understood what was happening. In fact, none of us did. But to be there in the moment, to be aware of one's own physical and mental experience in that moment and nothing more, was precisely the point.

This is but a snapshot of the different performances and events that make up Rapid Pulse. I personally have found the experience of working on the festival to be transformative and eye-opening. For many years I was somewhat dismissive of performance art myself, but I understand now that this was due to my own lack of understanding and willingness to engage. Now I am acutely aware of how my experiences with Rapid Pulse have begun to color the many other artistic initiatives I am involved in. In fact, many of the exhibitions I organize for the MCA involve performative aspects and are geared towards open-ended inquiry, improvisation, and the acceptance of the unknown. It has been rewarding, if not also liberating, to push myself beyond my own comfort zone and move into this other realm of artistic activity, for it is exactly these kinds of experiences—deeply affective and challenging as they are—that become all the more formative as one pushes onward, blindfolded and barefoot though we may be.