Extremely Mello

by Bryce Wilner

Leftover MCA wall vinyl in storage

Photo: Nathan Keay © MCA ChicagoAbout

In April of 2014, I walked by the recently closed exhibition BMO Harris Bank Chicago Works: Lilli Carré and was met with the words “Extremely Mello Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago. ®” where the show's wall text used to be. The MCA's preparators had composed a new message by strategically removing vinyl letters from the old title.

The Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago, like many museums, displays exhibition titles and texts on the wall using adhesive-backed vinyl. Vinyl text is typically installed in one block to ensure that each line is spaced and leveled as the designer intended. This is not true of the removal method for vinyl graphics. When an exhibition closes, the museum’s preparators uninstall the texts by removing the letters and punctuation one by one.

I believe the impulse to construct sentences or sentence fragments from moveable letterforms is common; rascally passersby rearrange marquee letters and households display loose, magnetic alphabets on their refrigerators. There is power in the act of reordering letters to compose new messages. Many MCA preparators—some of whom are artists themselves—are of this tribe.

Wall text strategically removed by MCA preparators

About

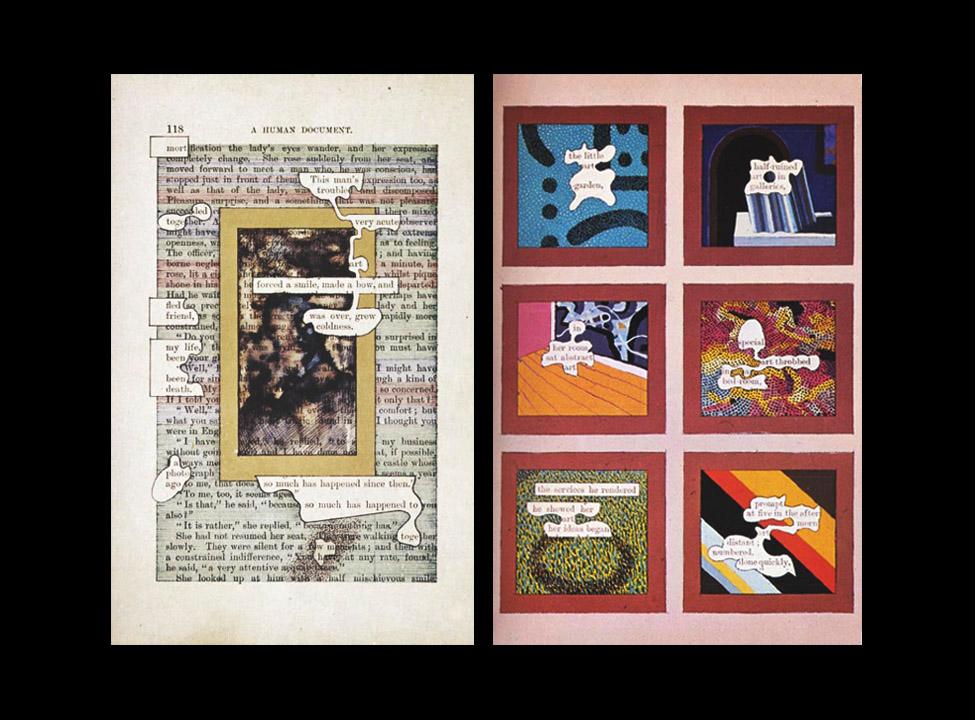

The interest in reordering language and the methods for doing so have precedents in the fine arts. In 1966, the British artist Tom Phillips began drawing, collaging, and painting over the pages of the 1892 novel A Human Document by W. H. Mallock. Inspired by the “cut-ups” (sentences pasted together from disparate sources) of William S. Burroughs and Bryon Gysin, Phillips began to form new sentences in the book by connecting words through the rivers of the preexisting text. From 1966 to 1970, Phillips constructed a loose narrative centered on a character named Toge, whose appearance was only made when Mallock used the words “together” or “altogether” in A Human Document.

Phillips published this “treated Victorian novel” under the name A Humument in 1970. To the conditioned reader, the meandering phrases brought together by his treatment cause the visual artwork to recede. The space around the words grows into an area of rest, and the reader is given a gift: the ability to reimagine the way in which a sentence can be read.

Pages from the first version of A Humument, 1966–73

© Tom PhillipsAbout

Uninstalling an art exhibition is a slow process. Walls are taken down, sculptures are disassembled, and rooms are repainted. The next time you visit the MCA, take note of which galleries are in this intermediate stage. There is a good chance that you will see a wall with words adjusted by an MCA preparator.

Wall text strategically removed by MCA preparators

Wall text strategically removed by MCA preparators

About

These thoughts returned to my mind in May of 2014, when I went to Chicago's Graham Foundation to see the artist Alison Knowles. She gave a reading to accompany her work on view in Everything Loose Will Land, the Graham's summer show surveying the art and architecture of 1970s Los Angeles. Knowles read an excerpt from her massive computer-generated poem A House of Dust, created with James Tenney on a Siemans 4004 machine in 1967. She then spoke in conversation with the art historian Hannah Higgins about The Identical Lunch, a performance wherein she asked her friends to try her favorite lunch at the time—“a tuna fish sandwich on wheat toast with butter and lettuce, no mayo, and a cup of soup or glass of buttermilk”—and write about their experiences. The humor of The Identical Lunch was not lost on her, and she shared laughs with the audience throughout the reading. The conversation then reached a small lull. Knowles raised both of her arms, hands holding two thumbs up, smiled, and exclaimed to the crowd, “There's poetry in ordinary things!”