Andrea Bowers

Featured images

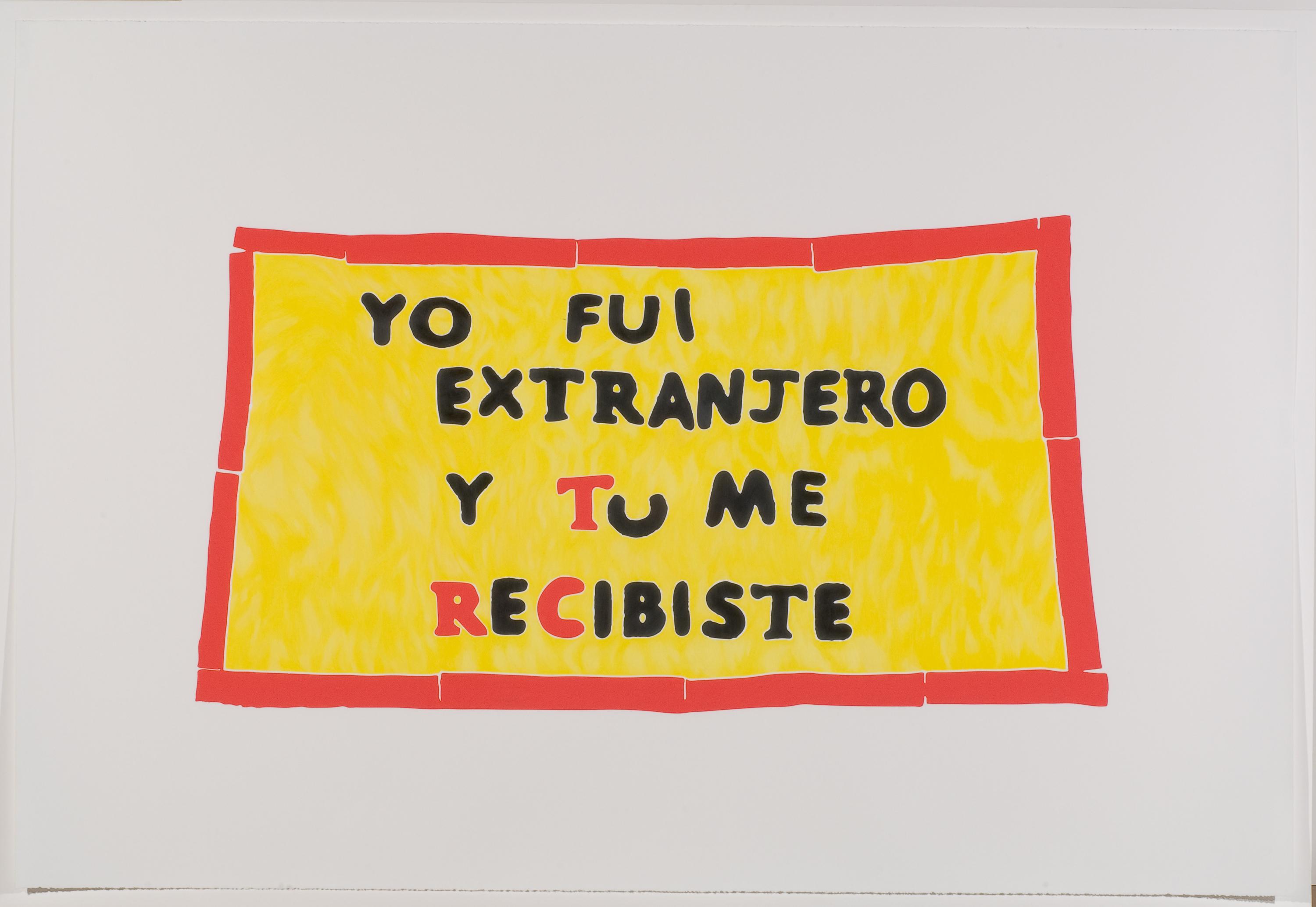

Andrea Bowers Church Banners (Adalberto United Methodist Church, Chicago, Member of New Sanctuary Movement), 2007/2008 Color pencil on paper Diptych; Each 50 x 74 in. (127 x 187.96 cm)

Private collection, Denver, Colorado. Courtesy of the artist and Vielmetter Los Angeles. Photo: Robert Wedemeyer

Andrea Bowers

I Am Nature: Champion International Clearcut; West Flank of the Cabinet Mountain Wilderness, 2013 Archival marker on found cardboard 118 1/8 x 157 1/2 x 1 1/5 in. (300 x 400 x 3 cm)

Andrea Bowers ”Can You Think of Any Laws that Give Government the Power to Make Decisions About the Male Body? Quote by Kamala Harris During Brett Kavanaugh’s Confirmation Hearing in 2018, (Frontispiece by Unknown Illustrator from Les Femmes Illustres, Ou, Les Harangues Heroïques, by Madeleine de Scudéry, Published by Chez Antoine de Sommaville & Augustin Courbé, Paris, 1644),” 2020

108 x 78 x 5 in. (274.32 x 198.12 x 12.7 cm) Courtesy of the artist and Vielmetter Los Angeles Photo: Jeff McLaneAbout the Exhibition

For over thirty years, multidisciplinary visual artist Andrea Bowers (American, b. 1965) has made art that activates. Bowers works in a variety of mediums, from video to colored pencil to installation art, and explores pressing national and international issues. Her work combines an artistic practice with activism and advocacy, speaking to deeply entrenched social and political inequities as well as the generations of activists working to create a fairer and more just world.

Born in Wilmington, Ohio, Bowers received her MFA from the California Institute of the Arts in 1992 and currently lives and works in Los Angeles. She built an international reputation as a chronicler of contemporary history, documenting activism as it unfolds and collecting research on the frontlines of protest through an empathetic and labor-intensive practice. Her subject matter contends with issues like immigration rights, workers’ rights, climate justice, women’s rights, and more, illustrating the shared pursuit of justice that connects these issues.

This is the first museum retrospective surveying over two decades of Bowers's practice. Highlights of the exhibition include Memorial to Arcadia Woodlands Clear-Cut (2013) and My Name Means Future (2020). These two works, both focused on issues related to environmental justice, highlight the range of mediums employed by the artist. The former is a large-scale sculpture based on her involvement with tree-sitting activists protesting the destruction of old-growth trees in California; the latter is a video that features Tokata Iron Eyes, a young Indigenous rights activist whose ancestral lands have been threatened by the Dakota Access Pipeline project.

Andrea Bowers is co-organized by Michael Darling, former James W. Alsdorf Chief Curator at the MCA, and Connie Butler, Chief Curator at The Hammer Museum. It is presented in the Griffin Galleries of Contemporary Art on the museum's fourth floor.

Partners

This exhibition includes contributions from two Chicago-based organizations, Centro Sin Fronteras and A Long Walk Home.

Centro Sin Fronteras

In 2007, Andrea Bowers documented and spent time with Elvira Arellano and Pastor Emma Lozano, two Chicago activists who worked with Centro Sin Fronteras, of a Chicago-based grassroots activist organization located in Humboldt Park. Bowers ultimately made a series of artworks based on their work with Arellano. The organization’s goal is to bring attention and justice to workers who were treated unfairly due to a lack of formal representation within the justice system.

Within the Andrea Bowers exhibition, Centro Sin Fronteras is presenting objects selected from their archive and a history of their work.

A Long Walk Home

While planning this exhibition, Andrea Bowers met with the Teen Creative Agency (TCA), the MCA’s cultural leadership program for Chicago teens. She invited them to offer a gallery space to important activists working in Chicago today. TCA chose an organization called A Long Walk Home, and to bring awareness to the issue of missing and murdered Black young women and girls. A Long Walk Home is a national, Chicago-based art organization that advocates for racial and gender equity and an end to violence against all women and girls.

Within the Andrea Bowers exhibition, A Long Walk Home is presenting The Black Girlhood Altar, a sacred site assembled by Black girls in Chicago for Black girls and young women who have gone missing or been murdered.

A Long Walk Home curated this playlist to accompany their MCA installation of The Black Girlhood Altar on the occasion of the exhibition Andrea Bowers.

Transcripts

An Eloquent Woman, 2009

Single-channel video (color, sound)

19 minutes, 12 seconds

CANDACE FALK: When I named my dog Emma Goldman I would never have imagined that I would have devoted most of my adult life to Emma Goldman. And it was the seventies. It was a time when politics and love and free love and drugs and music and everything was merged together and it was a wonderful thing. So to name your dog Red Emma, which is what I had done, was like carrying the spirit of exuberance, ecstasy.

So I was traveling across the country from where I had taught at a feminist institute— I had passed through Chicago, University of Chicago area, and I went to visit a friend of mine who worked in a guitar shop. And when I went to visit him, my dog, Red Emma, came bounding into this shop, knocked over these music stands, and my friend John Bowen, he just said, "What a lovely dog you have, what's her name?” And I said, “Red Emma Goldman.” And he looked at me as if I had said something that was just much more profound than the name of a person, and then he said, “I think that five years ago when I was cleaning the back of the shop, I think I saw some letters of hers.” So it took him a while. He came out of the back room with an enormous box, which turned out to be a boot box full of love letters. Her lover and manager wore big, high cowboy boots. [LAUGHS] So this was his boot box from his cowboy boots.

Well I don't know how to describe to you but I certainly had read Emma Goldman's autobiography Living My life, but I had never seen letters of hers and it was very exciting. I had a little hesitance when I opened the letters, when I was just looking at these letters, and they were all addressed to “Ben L. Reitman.” And I knew that he was this very critical person in her life. That he was not only the love of her life but he devoted himself to her work. And I had this amazing feeling that I was touching a piece of paper that Emma has touched; that the handwriting in some way said something about her mood that day. But I remember there was a reference to Ben Reitman's letters in her autobiography that said that his letters were like a narcotic to her. They made her heart beat faster, but they put her brain to sleep. So I started to open the letters, or just to open along the side, and I saw her handwriting, saw the letters, and I see that they all say “Dear Hobo.” And I thought, ah, I remember that he had been an advocate of hobos. It would be like being a homeless activist now. And I also knew he was a gynecologist. [CHUCKLES] And I say that because as I started to read the letters, I thought, oh my god, these are not just Emma Goldman speaking about freedom, the right to self-expression‚ all of her work, these were very, very passionate love letters. And at first, frankly, I just felt like there is something about documents that were intended for someone else, at that moment, where you feel like in a way it's a violation. And I wasn't really sure that I wanted to keep reading, but there they were, and just holding them in my hands was really exciting. And as I started to read them, the most evident thing was how sad they were. And it didn't fit. I was very young and it really didn't fit my sense of Emma Goldman, the powerful woman, you know, being so sad. And as I was reading them, suddenly— actually my partner, he came across this letter that said, "If anyone reads these letters I would feel naked." And I suddenly felt like I had violated Emma and that she was coming out of the grave almost, saying, "Put them away!"

I was thinking to myself that how could it be that her autobiography, which all of us loved so much, because it was so passionate, it was so political, and it really was not just about her, it was about a time and a place and an excitement and in the tone of victory—like even the worst situation she overcame. And these letters did not seem that way. One letter said that, "The world would stand aghast that I, Emma Goldman, the daredevil, the one who has defied laws and convention, should have been shipwrecked as a crew on a foaming ocean." Another letter said, "I have no right to bring a message of freedom when I myself have become an abject slave to my love."

Gradually the story unfolded that here was this woman who really wanted total freedom beyond all else, who believed that individual acts of kindness and goodness and openness, and at living your principles, was as important as any other policy or anything in the world that you have to change yourself, and that she would be the great example. And what she wanted was non-possessive love. And she spoke about free love, which in many ways at that time was also love outside of the state of marriage. But it also meant to her that you would have to abandon or exorcise jealousy. That jealousy kept you in bondage and you had to trust that love would come and go and keep the doors open. And yet, as it turns out, Ben Reitman, Mr. High Boots, big cravat, big hat, cape, was, you know, what they would call a ladies' man, and he drove her crazy. She would sometimes be giving a lecture on the false fundamentals of free love and saying, "Some people think free love is promiscuity but it isn't." It's kind of almost like she believed in serial monogamy in some way. But what she was really doing was hectoring her guy, saying, "You are promiscuous, stop it!" And so she would be speaking and he would be standing at the corner selling literature, but also seeing if he could catch the eye of a woman who'd caught his fancy and then he would leave with her, arm in arm, you know‚ have a quickie, and then come back. And often in their hotel room, which was even more terrible for her. So she just felt humiliated by him. And he was incorrigible. I mean I think he might have been a sex addict or whatever, but at that time, you know, it wasn't given a name. But she was completely in love with him.

And in the spirit of coming back to the documents, she obviously said— one of the letters said that "he had open the prison gates of her womanhood and all the passion that had been caught inside for so many years." Well, he was a gynecologist. He was one of the few men who understood sexuality. She had an orgasm after, as she would say, 38 1/2 years. So she was hooked. And she just felt that this was the other side. This was the, "she was civilization and he was savage," which is a horrible way of putting it really terribly, you know, but you know what she meant. Because she felt like viscerally so connected to him and so she was willing to put up with the torment.

I suddenly noticed how many letters there were that were coded. Now the codes that I had discovered early on with her love letters were really figuring out what "my TB longs for your W," and that was "my treasure box longs for your willy," and "my joy Ms": my joy mountains, Mont Jura and Mont Blanc. So that part was much more fun.

Now, our project is almost like a who-done-it. Every single day we realize that there almost wasn’t any kind of retaliatory violence that was happening in the US at her time where she didn’t have some knowledge of it or support for the people who did it. She hid people out. She raised money for their legal trials. She believed that she was a patriot. So she felt, along with her anarchist comrades, that violence had a place in the equation and that her hope among all other hopes was that violence was not the tactic of choice, but that when she lived, she could not see a pacifism that would scare people enough to back off and change.

Among some of the great finds of the Emma Goldman Papers, we figured out who threw the Haymarket bomb. Like most people wouldn’t know that. Nobody knows that. All the books that are out now don’t know that. That’s the kind of thing that you can unravel once you’re doing a very in-depth archive where you’ve been so close to the material that you know how to read between the lines and follow the tangent. Sometimes you come up with something that’s just really quite amazing.

What the Haymarket was in 1886, there was a bombing at a labor demonstration in Chicago in which several of those killed or injured were policemen. And subsequently, in 1887, hanging of the anarchists associated with the event, some of whom were wrongfully accused, initiated a cycle of fear and a correlation between anarchism, foreigners, and violence that would take years to unravel. From piecing together the available evidence we have found, there’s a revealing reference to a German shoemaker, one of the old German comrades, George Schwab, as the bomb thrower, who died in 1924 in the poor hospital. He got away. So all those men were innocent.

This is a letter to Ben Reitman, her lover hobo, written on Mother Earth stationary in their 210 East 13th Street office. On August 15, 1909, she writes, "Beloved Hobo, my life's own one, I love you. I love you, oh so desperately. You are light, air, beauty, and glory to me. You are my precious Hobo. Dearest, do you know that creepy, slimy, treacherous thing doubt? Have you ever been seized by it? Has your soul ever suffered its sting, your brain ever experienced its horror-beating force? If you have, darling mine, then you will understand how it is." Emma was jealous and doubting the love of her life, and this was a letter to Ben.

Here, the letters had an immediate quality to them, where you really feel like you knew what her mood was. You could feel her vulnerability. You could see her anxiety, and that her public face was the face of someone who was there to give other people faith that freedom was possible. And it isn’t that she didn’t think it was possible, but she herself struggled with the same issues but tried to portray herself as someone who rose above that. However, I felt at that moment, and I guess still, very privy to what her inner soul was. And to me, to see that was a thrill. It was difficult. But it was something engaging about feeling that her issues were not so far from the rest of us. That this person who was an icon was actually a human being as well. Even now I feel like I captured the woman and the person who had the ability to transcend not only the darkness around her and the world but also her own self-doubt and depression, really, to serve something that went beyond her.

Emma Goldman is gone. Gone to join that army of men and women of the past to whom liberty was more important than life itself. She spoke out in this country against war and conscription and went to jail. She spoke out for political prisoners and was deported. She spoke out against Nazism, and the combination of Nazism and Communism, and there was hardly a place where she could live. Emma Goldman, we welcome you back to America. We want you to end your days with friends and comrades. We had hoped to welcome you back in life. You’ll live forever in the hearts of your friends. And the stories of your life will live as long as the stories are told of women and men, of courage and idealism.

Circle, 2009

Single-channel video (color, sound), looped

17 minutes, 3 seconds

[BIRDS CHIRPING]

SARAH JAMES: My name is Sarah James, and I'm from Arctic Village, Alaska. Original name is Vashraii K'oo. It means "a place with high bank." I'm a chairperson to Gwich'in Steering Committee, and I'm one of the spokesperson on speaking on behalf of the Gwich'in Nation, on protecting the coastal plane of the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge.

We formed Gwich’in Steering Committee back in 1988. We made that decision united to go against the gas and oil development because that’s the very thing that’s causing climate change is fossil fuel. This year is a 20-year anniversary fighting oil and gas development of the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge because we’re not talking about all the oil development in the world, but we’re talking about coastal plane of the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge. It’s the birthplace of the Porcupine River caribou. They go there. That’s the only safe and healthy place for them to have their calf as a birthplace. Our Porcupine caribou travel maybe thousands of miles every year, and, come April, they go back up there. They migrate through here and over Canada, the whole Gwich’in area.

And then another thing that’s taught among all Gwich’in Nation and all Indigenous people is that the day that anything changed in the sky—that mean rain, cloud, sun, anything—if there’s any change in the sky, that means a hard time’s going to come. But now, it’s climate change. It’s in the sky. It’s the rain. It’s the cold. It’s the air. So I think that message is pretty clear among all the Gwich’in and Indigenous people. We used to have a good four seasons—spring, summer, fall, winter—but now that’s kind of mixed up sometimes. It gets mixed up. Like this winter, we went through— well, we didn’t get snow for a while, because we need snow when it starts getting cold, because it works like insulation. It covers the land. When that don’t come, it freezes the water deeper, so it just— it freeze out the fish spawn area, and it freeze out hibernating animals. And since I can remember— you know, I’m 65 years old right now, and even in my time I see a lot of growth, vegetation.

When the village first decided to settle here— because we are nomadic before that, and then the government said the kids have to go to school. So they chose this place. We call it Vashraii K’oo. Arctic Village came later, after the Western contact. It was a popular stopover when we were nomadic people because of that creek— got fish in it. All these lakes within this valley is connected somehow or another, and when fish are on the move, they go through like creek like that down here.

And this is a place where caribou tend to pass through when they’re on their migratory route. So they chose this place, and then there’s also a tree line then so they can build their cabins. And they can do trapping, they could do— and that’s why they chose this place. So now the tree line is past Brooks Range, way up north. So that’s how much growth it is since that time. Maybe about three grandma before me, that time.

Indigenous people are always considered— I mean, I guess environmentalists is our way of life. Protect the Mother Earth; protect the earth, and protect the land. And I think we’re born with it and will probably die with it because that’s our way of life.

[CHANTING, DRUMMING]

[APPLAUSE, CHEERING]

[DOGS BARKING]

LUCI BEACH: My name is Luci Beach. I’m the executive director of the Gwich’in Steering Committee. As executive director I do a little bit of everything, mostly administrative work and making sure things happen.

[WATER QUIETLY TRICKLING]

Not just in Arctic Village, but within the Gwich’in Nation, we’re seeing a lot of impacts. Permafrost is melting, and the lakes are draining out. You know, when it gets cold, we’ve had unusual times where there’s been icy rains in the middle of winter, which is very unusual, and the lakes and rivers not freezing up in the wintertime like they normally do, so people can get out, and hunt, and gather wood, and huge forest fires that have gone on year after year. These kind of impacts were predicted long, long ago by the elders, and the elders said that it would be because of what humans have done.

Except for the Arctic Refuge, pretty much most of the North Slope of Alaska is available to development, as well as offshore. So the fossil fuel development in Alaska is greatly contributing to climate change. And what we’re seeing with leaving few places off limits, like the Arctic Refuge, is how can we do things that aren’t going to harm the land, the air, the water, the people, the animals, and look at these things where we can make a future for the future generations, that they can have a good life that includes clean air and a climate that we haven’t completely disrupted.

The people in the north are seeing the changes firsthand. We’re seeing these changes, we’re living with them, and these changes are impacting us in a frightening way, and they really have to look at answers that make sense, that they’re just not for short-term profit for huge corporations. We’re just the beginning of the people that are feeling the impacts. This is going to happen around the world, and now is the time to really think about what we can do not to harm ourselves—ourselves meaning the people of the world.

SARAH JAMES: We govern ourselves on this land. We’re a Native village of intertribal government. We own 1.8 million acres. We didn’t go the Alaska Land Claims Settlement Act. We had this, what they called IRA, Indian Reorganization Act. Under that they got a title to a land back in 1938.

This guy, he went to college and he got his master’s degree. His name was John Fredson. He was at the mission because during the epidemic of TB, and flu, and everything like that, there was a lot of orphans, and got his master’s degree in Massachusetts. And when he came back, he told the people that we can apply for land. People don’t understand at that time. A lot of people didn’t understand it because they just don’t know the concept. But then he finally got a few people convinced, and they called a meeting in Venetie. Some of the Arctic Village people went down there, came up, and they wrote a letter to Secretary of Interior for tributary of this East Fork River down to the Yukon, to the Christian River, and they claimed that. It turned out that it was 1.8 million acres, and they applied for it, and Secretary of Interior approved it. And we got that title since then, but Alaska Land Claims Settlement Act passed in 1970, and they included us in that.

That means that rest of Alaska is under Alaska Native Land Claim Settlement Act. They call it ANCSA, and— which instead of landowner, they’re stockholder. They’re corporation, just like Western-type corporation. Yeah, we already have this option from 1938, so our people don’t understand the concept either. So we had to educate them, tell them the difference between these two. And then we took it to a vote after we educated them in 1970, and they voted—landslide vote—to stay with the IRA.

One of the first things we did to prove that we always govern ourselves, we always took care of people, is to stop the drinking alcohol because, like any other Indian Nation throughout the United States, alcohol is the problem among our people and still is. But that’s what’s really killing us, so we said we’re going to outlaw that.

Due to having a political position, we can’t receive state money or federal money, so we have to reach out to private foundations and private individuals. So we mainly reach out to— first, we reach out to grassroots organization, and right away the major environmental organization join up, but we couldn’t join them either because their interest is public interest land. Our interest is human rights because we always live here, and we’re not leaving. We’re here to stay, and we’ve always been here. So we have to educate the world in order to get the word out, and that’s very hard without money. It’s getting harder and harder with this economic crisis, but they’re still united and they’re still— it haven’t changed. The resolution haven’t changed. The unity haven’t changed. They say that’s the only way we’re going to do it, by being united.

[BIRDS CHIRPING]

AMANDA CARROLL: [SPEAKING GWICH'IN]

My name’s Amanda Carroll. I’m from Circle. I work with Luci Beach with the Gwich’in Steering Committee, so I just started that job. It’s been pretty nice working for my people. Gwich’in Steering Committee helps the people spread the word about saving the Arctic Refuge. I think this is the 20th anniversary for the celebration on the Arctic Refuge, and so far it’s been pretty good.

The main reason we’re trying to save the Arctic is because the caribou and the Gwich’in people are more one. Well, first of all, pollution. It’s a really big one in the Arctic because our animals feed off of the river and the land, and we feed off our animals, and it just goes in a circle of what we eat and what we use in life.

We have been having less snow each year. More ice melted, well faster than usual, and ever since I was growing up in Circle I’ve noticed a lot of things about climate change. And we got a really bad flood this year, and the whole Yukon River was high. I heard there was of a few villages that got wiped out, and there was a fundraiser going on this past weekend for them in Fairbanks at the tribal hall.

Well, I feel that everybody should get together and have one big powwow or something, and talk about what’s going on in the Arctic because not only it affects us here in the Arctic or in the interior of Alaska, it affects everybody in the whole world.

[BIRDS CHIRPING]

I Plan to Stay a Believer – The Arcadia 4 Tree Sit, 2013

Single-channel video (color, sound)

60 minutes, 55 seconds

[BIRDS CALLING]

ANDREA BOWERS: So John was like, "Meet us at this on-ramp at 2 or 2:30." And I was scared to death. And you guys were all in the cars. I had never met Julia. I just felt like a huge mess.

So we— I don’t know where we’re at. We drive to Arcadia. We pull into this driveway. And this neighbor, Cam, comes out, and brings us in, and he shows us the Google Maps, and shows us exactly the path we have to take and where the trees are and where the security guards are parked, because the neighbors have plotted out where all the security guards sit.

So we organize our gear as much as we can. We figure out who’s going to carry what. Because we had to carry water—

JULIA JAYE: Yep, water.

ANDREA BOWERS: —enough water. We took water and food for four or five days.

JULIA JAYE: We had these boards because you— when you’re tree sitting, and you’re really prepared, you have a board that you tie up into the tree so you can sit on that board. One was— the one that Travis and I ended up using was, I think, two by six. And how big was yours?

ANDREA BOWERS: Slightly bigger.

We had to climb up hills. We had to jump over a little ravine.

JULIA JAYE: Yeah.

ANDREA BOWERS: So it was just so much weight. And it was— we couldn’t use any flashlights.

JULIA JAYE: Uh-uh.

ANDREA BOWERS: We couldn’t use any lights because they would see you.

JULIA JAYE: Yep.

ANDREA BOWERS: I have no idea.

JULIA JAYE: Half an hour?

ANDREA BOWERS: An hour?

JULIA JAYE: No.

ANDREA BOWERS: Yeah, 45 minutes.

JULIA JAYE: Yeah.

ANDREA BOWERS: So by the time each group tried to even get in the tree, the sun was coming up.

JULIA JAYE: Yeah.

ANDREA BOWERS: So I was pretty sure that this was never going to work. I was pretty sure before we’d get in the tree that we were going to get busted. We would be caught.

And, in fact, security was driving around. And I was just ducking because John was already in the tree. And Travis probably got in the tree too, because they just climbed up it. They climbed it like you would just walk— pull yourself up a tree.

JULIA JAYE: Yeah.

ANDREA BOWERS: And I was at the bottom, and you probably were too, tying stuff to ropes and pulling it up the tree, which took a really long time and a lot of strength.

JULIA JAYE: Yeah.

ANDREA BOWERS: And so the sun's up, and I'm like, "I have to get up now." And I'm under a lot of stress because I know that I have to get up immediately. And I'm really panicking and I'm doing it, but I've never experienced such physical exhaustion.

And when I finally got up there, within two minutes, we were sighted.

Once I got in the tree and the sun came up, I had this moment where I stopped for just a second and got out of my head and looked around and thought, "My god, this is one of the most beautiful places I've ever seen." I mean, it was truly, truly beautiful. I couldn't believe what then happened.

NEWS ANCHOR 1: There’s a protest in Arcadia this morning to save some trees.

NEWS ANCHOR 2: LA County officials say they need to clear 11 acres of land for a flood control project. Eyewitness News reporter John Gregory joins us live in the Oak Grove area of Arcadia with a look at exactly what's going on. John.

JOHN GREGORY: Now, we were told there are four environmentalists inside this debris basin, actually camped out in several of these trees, and I believe we do have a view from AIR7 where you can see where they’re located. They are vowing to stay there as long as they have to, to protect this area. Meanwhile, the county has already started work on removing some of these trees. And the only thing clear right now is this is going to be a long and bitter fight.

Despite protesters camped in trees, the work is underway. The county has brought in heavy equipment to remove close to 200 trees on 11 acres, including more than 170 oaks, which environmentalists are vowing to save.

GLENN OWENS: They’re willing to stay there until hell freezes over. They’re trying to take down a lot of trees, and it’s unnecessary. They don’t have to. There’s enough room for the sediment on another pile.

DAVID CZAMANSKE: This is not just one or two trees here and there, it’s what we call an oak woodland habitat, okay? It’s very unique, very rare here.

JOHN GREGORY: The county wants to clear the trees to make room for sediment from the nearby Santa Anita Dam. Still, protesters insist there has to be another way. And some are willing to sit in these trees until someone finds it.

DAVID CZAMANSKE: We believe there are several other alternatives that they could do, without delay of cost, without delay of time, that are quite reasonable.

JOHN GREGORY: Now, back live here on the ground, and you can see the environmentalists have their signs out, the barriers are up; so really, the battle lines being drawn here in this normally quiet Arcadia neighborhood. We're live in Arcadia. John Gregory, ABC 7, Eyewitness News.

[MACHINERY BEEPING, LEAVES AND EQUIPMENT RUSTLING]

ANDREA BOWERS: Can you see anything, John?

JOHN QUIGLEY: No, there's not [INAUDIBLE]. I mean, they're using the [INAUDIBLE].

Uh, we're in oak trees that would be part of the [INAUDIBLE] right across from the [INAUDIBLE].

[MACHINERY BEEPING]

You can see people [INAUDIBLE]. That's my take on it. Just because it's close to the road but— so if people want to rush the gate and run in here and start hiding in trees, now is a good time.

[MACHINERY BEEPING AND RUMBLING]

[JOHN CLEARS HIS THROAT]

[MACHINERY BEEPING]

JULIA JAYE: So the first trees that I saw coming down at that point, I just saw the tops, I think they were sycamores, just falling in this thud. And it was then that I started screaming to try and get their attention.

[EXCAVATOR WHIRRING AND BEEPING, WOOD CRUNCHING]

And then everything stopped. A few minutes later, a man walked up to our tree and I was relieved that, okay, now we’ve moved into a new realm. Now they know we’re here.

ANDREA BOWERS: Do you guys know what time it is, can you tell me?

SHERIFF: It’s time to come down.

ANDREA BOWERS: Yeah, besides that, is it—

SHERIFF: 5:01.

ANDREA BOWERS: 5:01? Thanks.

[EXCAVATOR WHIRRING AND RUMBLING]

So John, tell me what’s going on.

JOHN QUIGLEY: Well, here’s one of these things that just kind of came out of the blue. Hearing about these woodlands and meeting the people who are fighting to save it and—

ANDREA BOWERS: So we’re in Arcadia, right?

JOHN QUIGLEY: We’re Arcadia. We’re in a place called the Santa Anita Wash. It’s the last alluvial oak woodlands in the San Gabriel Valley, just coming off the mountains.

And all told there’s about 26 acres, and today they’re going to cut somewhere between 11 and 13, and that’s what they’re scheduled to do. So we mobilized at the last minute to see if we could help. And so here we are and they’re starting to cut, and it’s brutal. It’s just brutal.

[WOOD CRUNCHING, EXCAVATOR WHIRRING AND BEEPING]

ANDREA BOWERS: There were always, what, 5 to 10 sheriffs underneath the tree at all times.

JULIA JAYE: Circling.

ANDREA BOWERS: Circling.

JULIA JAYE: Yeah.

ANDREA BOWERS: There were times when they disappeared, but not for very long. Some people down at city hall who were in charge were called. First of all, they were trying to get them out of the tree, but I think there was also a very quick meeting that was held to decide what to do with us.

JULIA JAYE: Yep.

ANDREA BOWERS: The decision must have come down that was simply to keep cutting, rip that forest out no matter what. Do it as much as possible, and do it to the point where you scare them. I think the goal was to scare us out of the trees.

JULIA JAYE: Absolutely. They didn’t hide that at all actually. There wasn’t a point, throughout the whole experience, where my safety was assured by anybody on the ground. In fact, it was quite the opposite. They were getting as close as they possibly could, trying to intimidate us very violently.

[EXCAVATOR WHIRRING AND RATTLING]

ANDREA BOWERS: So the next one is the tree right here next to us, John.

JOHN QUIGLEY: Right. I think if they start coming after that tree, it’s going to be a nightmare.

ANDREA BOWERS: I think so, too. This is actually getting scary. I mean, that tree—

[EXCAVATOR WHIRRING LOUDLY]

I mean it could—

JOHN QUIGLEY: Hey.

ANDREA BOWERS: Hey!

JOHN QUIGLEY: Hey.

ANDREA BOWERS: Hey!

JOHN QUIGLEY: Hey.

ANDREA BOWERS: Hey, that tree can fall on us. You better stop him. Come on!

[EXCAVATOR BEEPING AND WHIRRING, WOOD CRUNCHING]

JOHN QUIGLEY: Hi.

[EXCAVATOR BEEPING AND WHIRRING, WOOD CRUNCHING]

Alright, yeah. Well, I’ll just— Hey.

ANDREA BOWERS: Hey, that’s going to hit us.

JOHN QUIGLEY: The tree right next to us is going to fall on us right now. What's that? Oh, no, they got this big bulldozer, crane thing that is destroying this beautiful oak tree right next to us, maybe 40, 50 feet away. If it falls in this direction, we could die. The limbs are interconnected with the tree that we're in [INAUDIBLE].

It’s still incredible. It’s so incredible. This area is just such a beautiful area.

[OVERPOWERING SOUND OF METAL CLANKING, LEAVES RUSTLING]

. . . destroying the tree. So I'm [INAUDIBLE].

[MACHINERY BEEPING, METAL CLANKING]

What’s that?

[METAL CLANKING]

We had some talks. [INAUDIBLE]

Wow.

ANDREA BOWERS: Wow.

JOHN QUIGLEY: Wow. They are cutting so close to us. It's like really— this guy is out of control. I mean they're just knocking over trees. One landed not 10 feet [INAUDIBLE]. We talked to them first thing this morning, but since then it's [INAUDIBLE]. We haven't really had a conversation.

Yeah, they asked us if we were going to come down, and we said no. We wanted to stay if they allowed it. And it was all very polite and friendly. And they were just— [INAUDIBLE]. Whoa.

[INAUDIBLE OVER METAL CLANKING, WOOD CRUNCHING]

ANDREA BOWERS: This is scary as hell. This is scary.

JOHN QUIGLEY: [INAUDIBLE OVER MACHINERY RUMBLING, BRANCHES CRUNCHING] . . . plenty of alternatives.

ANDREA BOWERS: Oh my god.

JOHN QUIGLEY: Oh, yeah, I don't know. [INAUDIBLE].

ANDREA BOWERS: John, they’re going for that tree right next to us.

JOHN QUIGLEY: They're literally [INAUDIBLE] branches [INAUDIBLE].

[MACHINERY WHIRRING, WOOD CRUNCHING]

ANDREA BOWERS: Oh my god.

JOHN QUIGLEY: Wow.

ANDREA BOWERS: I’m so scared. Hey, I’m really scared, you guys. I’m really scared. I’m really afraid. I can’t get down.

JOHN QUIGLEY: I mean there's like 20 [INAUDIBLE].

ANDREA BOWERS: Do you understand how dangerous this is?

[MACHINERY BEEPING, METAL CLANKING]

JOHN QUIGLEY: Yeah, so I was thinking, no one— because we all agree with the sentiment that even if we move, the question is what the city will do with this land. Because this solution does not— There are far better solutions to accomplish this and still save this area and all the habitat that's here. And so it's just a question of [INAUDIBLE OVER WOOD CRUNCHING] and [INAUDIBLE] ladies and gentlemen and stump. We talked about alternative number five. So that [INAUDIBLE].

I don't know if you have his number. But he could tell you about alternative five and when I heard about it, I said this is the far better alternative [INAUDIBLE] especially since it's so rare, this habitat in San Gabriel Valley.

So that's— I just want to make that very clear. We recognize that there's a new need to [INAUDIBLE] disagree with [INAUDIBLE], but there are other ways to— Sorry, we got a [INAUDIBLE].

Yeah, I will. And I'm sorry, what was your name again? Miriam [INAUDIBLE]. Thanks. Thanks, Miriam. They definitely need to back off. Otherwise they're seriously going to endanger our lives. [INAUDIBLE] Okay, thanks, Miriam.

[METAL CLANKING LOUDLY]

ANDREA BOWERS: I had no idea—

JOHN QUIGLEY: Hey, dude. [INAUDIBLE]

[METAL CLANKING, MACHINERY WHIRRING, LOUDLY]

Dude.

[WOOD CRACKING, METAL CLANKING LOUDLY]

Hey, listen gentleman, you got an out-of-control crane operator who’s literally knocking down trees that are connected to our tree. I don’t know who you can— Yeah, I mean, out of control, out of control.

ANDREA BOWERS: I’m scared.

JOHN QUIGLEY: [INAUDIBLE] Looks like he's [INAUDIBLE]. I mean it's serious, serious [INAUDIBLE]. I don't know who you can tell, but I'm just letting you know.

Oh, yeah. I understand. [INAUDIBLE OVER EXCAVATOR WHIRRING] . . . there still would be sycamores, but that [INAUDIBLE] this place [INAUDIBLE]. It's just sad.

[EXCAVATOR WHIRRING]

Okay. You might [INAUDIBLE].

[ENGINE RUMBLES AND THEN IDLES]

ANDREA BOWERS: John, what do we do?

JOHN QUIGLEY: [INAUDIBLE]

[EXCAVATOR CLANKING AND WHIRRING]

WORKER: Take these down and take these down. So make sure we push him that way. As soon as we get these down [INAUDIBLE] we'll have [INAUDIBLE]. Now we got to walk—

SHERIFF: Hey, John. We need you to come down now. We understand the cause, but we need you to come on down because we are using some heavy equipment to move these trees. Okay? Just like urban farm, we’re going to do the same thing. All right?

JOHN QUIGLEY: I know you’re doing your job.

SHERIFF: All right. And you got any questions for us?

JOHN QUIGLEY: Andrea, do you have any questions?

ANDREA BOWERS: Don’t hurt me.

SHERIFF: No, nobody is going to hurt you.

JOHN QUIGLEY: What’s that?

SHERIFF: You guys even saved the treestand from urban farms.

ANDREA BOWERS: Yeah.

JOHN QUIGLEY: Yeah.

SHERIFF: All right.

ANDREA BOWERS: [LAUGHS]

JOHN QUIGLEY: That’s wood man. We love trees.

SHERIFF: Hey, no problem, John.

JOHN QUIGLEY: Yeah.

SHERIFF: Okay. We’ll talk some more during this thing, okay?

JOHN QUIGLEY: Okay.

ANDREA BOWERS: I thought two trees out. I thought these trees are so close to us, they’ll stop within two trees. Like it won’t be the tree next to us and then won’t do the one after that. They’ll stop, and they’ll create a little grove around us. But before I knew it, they were ripping out the trees that were 10 feet away from us. The trees right next to us.

[MACHINERY BEEPING, WOOD CRUNCHING]

JOHN QUIGLEY: [INAUDIBLE OVER MACHINERY] No. No.

ANDREA BOWERS: And really don’t do that. Please?

JOHN QUIGLEY: No. Dude, this is going to go this way.

[MACHINERY RUMBLING AND BEEPING]

[WOOD CRUNCHING, MACHINERY RUMBLING]

ANDREA BOWERS: John, do you know what’s going on with Travis and Julia?

JOHN QUIGLEY: [INAUDIBLE]

[MACHINERY BEEPING AND RATTLING]

MAN ON RADIO: [INAUDIBLE OVER STATIC]

MICHAEL MARTINEZ: Your conduct is in violation of Penal Code Section 602, trespassing. I command you in the name of the people of the State of California to disperse and come down the tree and leave the property. If you do not, you shall be arrested for violation of Penal Code Section 602, trespassing. You going to come down the tree?

JULIA JAYE: So is that any different than what’s already been the situation?

MICHAEL MARTINEZ: Well, I’m giving you the official warning and giving you every opportunity to give yourself up and come down.

JULIA JAYE: And then what happens after this?

MICHAEL MARTINEZ: Well, [LAUGHS] I said you get arrested. If you refuse, then the additional charge of—excuse me—interfering with my performance and my duties becomes 148 of the Penal Code. You're also subject to that arrest. So again, I'm going to ask you to come on down.

All right, ask them individually?

TRAVIS: Yeah, it’s too bad the county is going to walk on the people. Because you’re part of the people, too.

MICHAEL MARTINEZ: Hey, well, is that a refusal?

TRAVIS: You’ve got to stand up for the people. You guys are not standing up for the people.

MICHAEL MARTINEZ: I just need to know, are you refusing to come down?

TRAVIS: I don’t understand your questions.

MICHAEL MARTINEZ: Okay. Julia, are you refusing to come down?

JULIA JAYE: I plead the Fifth.

MICHAEL MARTINEZ: Okay. All right. We’ve given them ample opportunity to come down. All right.

OFFICER: And we are off tape. It is January 12 at 13:48 hours.

TRAVIS: I didn’t understand anything that you said, sorry.

MICHAEL MARTINEZ: I am Sergeant Michael Martinez, and I represent the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department. Your conduct is in violation of Penal Code Section 602, trespassing. I command you in the name of the people of the State of California to come down from the tree and leave the property. And if you do not, you shall be arrested for violation of 602 of the Penal Code.

JOHN QUIGLEY: So you’re saying if we come down you won’t arrest us?

MICHAEL MARTINEZ: Well, what I will do is detain you and unless somebody wants to make a private person’s arrest, I will not be arresting you. But then you have to come down the tree now. You got that?

JOHN QUIGLEY: All right. We’re going to conference.

ANDREA BOWERS: Can we have a minute to talk?

MICHAEL MARTINEZ: Sure.

ANDREA BOWERS: Okay.

JOHN QUIGLEY: Here’s the thing. I’m not sure that I trust him.

ANDREA BOWERS: Yeah.

JOHN QUIGLEY: And we just got a call from one of the neighbors saying that they want to help us if we make it to the night. So I don’t think it’s in me to just go down.

ANDREA BOWERS: Okay, that’s fine.

JOHN QUIGLEY: But you can go if you want. For me— No, seriously, it’s your choice. I’m not saying you would, I’m just saying—

ANDREA BOWERS: I’m not going to get out now.

JOHN QUIGLEY: What’s that?

ANDREA BOWERS: I’m not going to get out now. What do I do if they arrest me? What happens to me?

JOHN QUIGLEY: They’ll arrest you, and then you’ll have to go to court and do all kinds things. You’ll go to jail right now.

ANDREA BOWERS: Fuck.

JOHN QUIGLEY: So I think what I’m going to say is I’m going to say, look, will they spare this tree? Which, of course, he’s going to say no.

ANDREA BOWERS: Right.

JOHN QUIGLEY: And then I'll say, "Okay, you guys do what you need to do."

ANDREA BOWERS: How much money is this going to cost me?

JOHN QUIGLEY: What’s that?

ANDREA BOWERS: How much money is this going to cost me?

JOHN QUIGLEY: I have no idea.

ANDREA BOWERS: How much did it cost you last time?

JOHN QUIGLEY: We had a pro bono lawyer.

ANDREA BOWERS: Yeah, but what about the fees?

JOHN QUIGLEY: What’s that?

ANDREA BOWERS: What did they charge you?

JOHN QUIGLEY: $200.

ANDREA BOWERS: Okay. All right.

JOHN QUIGLEY: I just think we’ve come all this way and then just walk out?

ANDREA BOWERS: Right.

JOHN QUIGLEY: I can’t do that. It’s not in my blood.

ANDREA BOWERS: Okay. Okay.

MICHAEL MARTINEZ: John, Andrea? Guys, coming down?

JOHN QUIGLEY: We thank you for your offer but we can’t really come out unless— after going through this, we would like these trees saved, and I know that you’re not in a position to negotiate that.

MICHAEL MARTINEZ: Okay. I just want to let you know that by failing to come down from the tree, you are delaying me from my lawful duties, and therefore you are also in violation of 148 Penal Code section, which is basically obstructing with a peace officer during performance of their duties, and you are subject to that additional charge, okay? So once again, I’ll ask you, please come down from the tree.

JOHN QUIGLEY: Well, I appreciate the way you asked. It was very nicely. I just— you guys could think of it as a field exercise.

MICHAEL MARTINEZ: Okay, sir. I’ll accept that as your refusal. Thank you. Ma’am, I assume you are also— is that yes?

ANDREA BOWERS: Yeah.

MICHAEL MARTINEZ: Okay, thank you.

[MACHINERY BEEPING AND RUMBLING]

ANDREA BOWERS: They’re shooing away the people with the cameras.

[MACHINERY RUMBLING, MUFFLED VOICES SPEAKING]

[EXCAVATOR RUMBLING, LEAVES RUSTLING]

This is crazy. I’m like— this is, like— they ripped everything out. This is the most uncomfortable thing I’ve ever done. And then there’s nowhere to sleep on this platform. I mean, I’m like totally wired in. I’m laying down right now because my back hurts. There’s cops over there. And then across the way are the others tree sitters. So I don’t know how they’re doing. Because we’re running out of batteries, of course, on the phones.

[MACHINERY RUMBLING AND BEEPING]

[WOOD CRUNCHING, MACHINERY RUMBLING]

[METAL CLANKING, MACHINERY WHIRRING]

ANDREA BOWERS: I knew they were coming in for us because the bulldozers dug roads to our trees. So I knew— because the ground was so natural and crooked and there were giant rocks with cacti, and so these bulldozers— so I remember yelling down, "So I guess you're now digging paths to us, you're digging roads." And one guy looked up and he said, "Yep."

[EXCAVATOR SQUEAKING AND RUMBLING]

John they’re making a path for the fire truck.

[WOOD CRUNCHING, EXCAVATOR RUMBLING]

JOHN QUIGLEY: So Andrea, your first real tree save.

ANDREA BOWERS: It was pretty hardcore in a way, so far.

JOHN QUIGLEY: Hey, how it goes?

ANDREA BOWERS: It was really emotional actually. It was really stressful and worrying about getting out here, and the physical part of really quickly in the dark trying to get up, but then, by the light of day the bulldozers started. And we’re in this beautiful tree, and I couldn’t believe how close the bulldozers got. I mean, they tore down the trees right next to us.

And, I mean, I thought it was really irresponsible. I thought it was crazy actually that they did that. But then, to spend the whole rest of the day sitting up here watching them tear out one beautiful tree, really old tree, after another. I mean, it seems just so— immoral is not even the right word. It’s like I— it’s just devastating for me. It’s really devastating. So, I guess this is what it means to bear witness, huh?

JOHN QUIGLEY: Right. Yeah. I mean, that’s— very quickly I got into this is about bearing witness.

ANDREA BOWERS: Yeah. That’s all you can do, really.

JOHN QUIGLEY: I mean, at this point, because it was so clear that they were hell-bent on doing this. And in some of the crazy stuff they did, coming so close to us, trying to intimidate us, and stuff like that.

ANDREA BOWERS: I noticed there are broken branches from the other trees hanging in this tree.

JOHN QUIGLEY: Yeah. Yeah, no. That was—

ANDREA BOWERS: That is crazy.

JOHN QUIGLEY: Yeah, that’s— so that’s, you know. But—

ANDREA BOWERS: I was shocked by how quickly they can take out a forest or something before us.

JOHN QUIGLEY: Yeah, especially in that way. You know, there’s a new sound that will haunt me.

ANDREA BOWERS: Yeah.

JOHN QUIGLEY: The sound of a chainsaw used to haunt me. And literally—

ANDREA BOWERS: This is worse, maybe.

JOHN QUIGLEY: I don’t know. It’s going to sit with me. In a way it is, I mean, because now I’ve witnessed it. I’ve witnessed trees cut by chainsaws, but I’ve never seen a whole forest devastated like this and then they just pick the tree up and throw it like it’s a little rag doll. This majestic oak that had stood for 100 years, two minutes before, and now it’s just being tossed and—

ANDREA BOWERS: It’s a splinter or a broken toothpick is what it looks like from here. It’s crazy. You know how huge that tree is.

JOHN QUIGLEY: Yeah, right.

[MACHINERY RUMBLING]

[BIRD CHIRPS OVER MACHINERY]

JOHN QUIGLEY: Is that— birds.

[BIRD CHIRPING SLOWLY FADES]

[MACHINERY RUMBLING]

ANDREA BOWERS: So that was in the late afternoon, and the sun was starting to go down. And the weirdest thing happened. There were no trees left, and all of a sudden animals started to come into the tree we were in because it was the only tree left. We were suddenly swarmed by bats encircling us, all different kinds of birds.

There were actually rats running into the tree. I mean, it was craziness because it was the last of the little bit of this ecosystem— bugs, moths. It was devastating. It was depressing because you realized how many other animals’ habitats and insects’ habitats had been destroyed in an afternoon.

[MUFFLING SPEAKING, MACHINERY IDLING]

[WHOOPING]

ANDREA BOWERS: What’s happening, John?

JOHN QUIGLEY: They are taking them out.

ANDREA BOWERS: They got a cherry picker, and they’re taking them out?

JOHN QUIGLEY: Yeah. And I think they brought in climbers.

JULIA JAYE: A search-and-rescue man came up to the tree and informed us that we were not spending the night in the tree. And we could either come down peacefully or they would extract us. And it was at that point that Travis and I said, "We need to have a little meeting amongst ourselves, can you give us a few minutes?"

And we talked about what we wanted to do at that point. And it was already at a point where all the trees besides two or three of them were totally torn down. And we had made whatever statement we were going to make. And because it was important throughout the whole process for it to be a nonviolent action, direct action, we did come down peacefully.

[MACHINERY IDLING]

JOHN QUIGLEY: This is pretty sad.

ANDREA BOWERS: Looks like they got somebody down.

WORKER: You good right there?

TRAVIS: No.

WORKER: Yeah, hold on.

WOMAN: Woo!

[WHOOPING]

ANDREA BOWERS: Woo hoo! [LAUGHS] I see Travis.

MAN: [HOOTING]

OFFICER: [INAUDIBLE]

JOHN QUIGLEY: Yay.

ANDREA BOWERS: Hey.

JOHN QUIGLEY: Hello.

MAN: Okay, it’s January 12, 2011. We are at Arcadia with the people that won’t come out of the trees. It is now 19:15 hours and ESD is getting ready to go up there and take the last two people down.

GURSKY: John?

JOHN QUIGLEY: Yes.

GURSKY: It's [INAUDIBLE] Gursky.

JOHN QUIGLEY: Hey.

GURSKY: Hey, we’re obviously going to come up and get you out, wanted to know if you’re going to come down voluntarily without resistance.

JOHN QUIGLEY: I’m going to be peaceful, and I’ll be safe.

GURSKY: Peaceful and safe without or with locking devices? John?

JOHN QUIGLEY: Yes.

GURSKY: Come on, we’ve been straight with each other.

JOHN QUIGLEY: What’s that?

GURSKY: With or without locking devices?

JOHN QUIGLEY: The process will be safe.

GURSKY: The process will be safe?

JOHN QUIGLEY: The process will be safe.

GURSKY: And you’ll cooperate, correct? John?

JOHN QUIGLEY: Yes.

GURSKY: And you’ll cooperate?

JOHN QUIGLEY: As I said, I’m here to protect this tree, and I’m a peaceful person.

GURSKY: I understand, John. Andrea? Andrea?

ANDREA BOWERS: Yes, I’ll cooperate.

GURSKY: A little louder, please. The same for you, you’re going to come down peacefully?

ANDREA BOWERS: I will be peaceful.

GURSKY: Okay, great. And you’ll do so without using any locking devices?

ANDREA BOWERS: I’ll be safe and peaceful.

GURSKY: Okay, thank you. All right. Secure yourselves while we come up.

ANDREA BOWERS: Okay.

GURSKY: Okay. By the advisement both indicate that they would come down peacefully. They’re not indicating whether they’re using locking devices. Go ahead and shine on them one more time.

Okay, sorry about the bright light, we just got to get this done.

Okay, Brian.

[ENGINE REVVING, MACHINERY BEEPING]

[MACHINERY IDLING]

MAN: Yeah.

[MACHINERY IDLING]

[LEAVES CRUNCHING UNDER FOOT]

[MACHINERY IDLING]

GURSKY: Hi, ma’am.

ANDREA BOWERS: Hi.

GURSKY: Proctor, a little bit higher. Now ma’am, I need your camera, please.

ANDREA BOWERS: It’s locked onto me.

GURSKY: What’s that?

ANDREA BOWERS: I don’t know that I can get it off me.

GURSKY: Well, we are going to have to get it off of you, okay?

ANDREA BOWERS: How about I just leave it hanging on me?

GURSKY: Oh, hang on you?

ANDREA BOWERS: Yeah, it’s hanging on me. Can I do that?

GURSKY: Can you turn it off for me, please?

OFFICER: Turn off—

ANDREA BOWERS: Huh?

OFFICER: Turn off—

GURSKY: Turn it off for me, please.

[MACHINERY IDLING, MUFFLED VOICE OVER RADIO]

All right, Tucker.

TUCKER: On the way down?

GURSKY: Yeah, down please.

TUCKER: Coming down. Clear?

[ENGINE STARTING UP]

[MACHINE RUMBLING]

[CHATTER]

GURSKY: That way we can get back up to the—

[CHATTER]

OFFICER: We got it. We’ll make our way up to the pickup trucks.

GURSKY: Thanks, buddy.

WORKER: You good?

GURSKY: Almost. Hang on one sec.

[MACHINERY RUMBLING]

WORKER: How’s that?

GURSKY: Yeah, that’s good.

[MACHINERY IDLING, LEAVES RUSTLING]

Rope.

Hey, Tucker.

TUCKER: Sir.

GURSKY: All right. We’re ready to come down to get this gear repositioned for the higher up one.

TUCKER: Coming down.

GURSKY: Thank you.

[ENGINE STARTING UP]

[MACHINERY RUMBLING, LEAVES RUSTLING]

WORKER: Hey, Jess, how do you guys— do you feel stable?

MAN: Yes, yeah.

WORKER: What do you want, up and forward?

MAN: Huh?

WORKER: Up and forward 10?

MAN: Up and forward, like 7 or 8 feet.

WORKER: Copy.

[MACHINERY RUMBLING]

How’s that?

GURSKY: You guys be careful when you [INAUDIBLE].

MAN: Yes, sir.

[MUFFLED SPEAKING]

MAN: Hold on.

WORKER: Hold on, Tucker.

WORKER 2: Let me [INAUDIBLE] the light when you pick them up?

MAN: Yeah.

[MUFFLED SPEAKING]

MAN: All right, we’re good.

WORKER: Clear.

[MACHINERY RUMBLING]

MAN ON RADIO: [INAUDIBLE OVER STATIC]

MAN: Yeah, [INAUDIBLE].

GURSKY: All right, guys, [INAUDIBLE].

ANDREA BOWERS: We were charged with trespassing—

JULIA JAYE: —trespassing and obstructing an officer because we didn’t come down. And for that, $10,000 bail.

LESLIE MILLER: Noted tree sitter John Quigley and three other protesters were perched high in the trees as a show to protect the Arcadia woodlands. They said they were prepared for the long haul but tonight in a turn of events, they are back on the ground and not the way they were hoping.

John Quigley, seen here in the dark blue jacket, and three other tree sitters are handcuffed as they are driven away by sheriff’s deputies. The environmental activists were talked down without incident by Special Enforcement Negotiators around eight o’clock tonight.

JOE FENNELL: We took a forklift up and we assisted them in coming down. They didn’t say anything other than they gave some type of signals, and the voices that we couldn’t understand, but they gave each other whatever signals they do give. And they all joined together and came down.

LESLIE MILLER: Tonight, dozens of Quigley’s supporters, including actress Daryl Hannah, turned out for a candlelight vigil in honor of the tree sitters and the trees.

KIM CLYMER-KELLEY: It was carnage. I mean, what they did to those trees, they went in and just bulldozed them. I mean, totally tore them to pieces.

LESLIE MILLER: John Quigley and the three other tree sitters are tonight being booked for trespassing and delaying a peace officer. Now, Quigley is noted for once holding a protest perched in a tree for 71 days. Reporting live in Arcadia tonight, Leslie Miller, ABC 7, Eyewitness News.

[BIRDS CHIRPING AND CAWING, INSECTS BUZZING]

Letters to an Army of Three, 2005

Single-channel video (color, sound)

55 minutes, 35 seconds

WOMAN 1: May 21, 1968. Los Angeles, California. My daughter is mentally ill and is not able to care for a child. Please send me a list of doctors in Tijuana that take care of abortions. Thank you.

WOMAN 2: March 6, 1968. Fresno, California. When I called about an abortion, the girl I spoke with said that you only had lists of doctors outside of this country. When I inquired about any in California, she asked if I was willing to take the legal responsibilities. If that is the problem, yes, I would. Prior to speaking with her, however, I understood that the main problem of obtaining the names of any California doctors was the law forbidding sending a list of that sort through the mail.

If there is any way of getting a doctor closer than Mexico—the only country of those mentioned to me, which is at all feasible. I would be willing to accept the legal responsibilities and come up to San Francisco, so you won’t need to send anything through the mail. I am nine weeks along, according to my doctor, and need to take care of this very quickly.

Could you also give an estimate of cost? If you prefer, and you can help me contact a physician in California, you can call me person-to-person collect. If you can still only give me the name of a Mexican doctor, please use the enclosed envelope as soon as possible. Thank you very much.

WOMAN 3: May 21, 1968. Los Angeles, California. I received your name and address from my reverend in Santa Monica. I’ve seen him recently to discuss my problem in detail and have concluded that an abortion is the only answer right now. I am married, but my husband has just been called for jungle training in Korea for a period of active duty for 18 months. I will be self-supporting, so a child would cause too many problems at this time.

I want to be sure this is a pretty hygienic group of doctors. I’ve heard so much about the terrible conditions of Mexico. But I feel that even that I’ve heard a few bad things, this is the only answer. If you could, I wish you’d rush this to me because my husband is leaving June 4, and it must be done before then.

I would also like to know if any of these doctors would do this on Sunday because I work all week and it would be the only day besides Saturday that I can make the trip down there. Please give me the information, and also how to get in contact with them. I can’t tell you how important this is. So please, hurry.

Also, I wish for you to mail the package to my office. But please do not put your return address on the envelope, as my employer is a devout Catholic and I think it may cause trouble.

MAN 1: June 22, 1968. A young lady that I’ve been dating has become pregnant. While we enjoy each other’s company, neither of us wishes to be forced into marriage. I don’t want her to have to go through a pregnancy, even if she gets all proper medical care. I feel a pregnancy is for those who intend having children with their husbands.

The girl’s about two and a half months pregnant, so there are no pills that will help. Where can we get an abortion? Although we’d prefer something local, I’d come north with her in order to prove our sincerity. Please help.

WOMAN 4: I’m 18 years old, single, and three months pregnant by a married man. I need the name of a doctor, for I’m in a desperate situation and I want an abortion. I have $200 in the bank and can get $100 more if I tried. Please help me because if you don’t, I’m going to have to kill myself.

I read your article in the Free Press of LA, and you are my last resort. I don't want my family to know, so I'm sending a self-addressed envelope. Please help. If you don't, no one else can.

WOMAN 5: Walla Walla, Washington. I’m a married woman, with four children, and I’ve just discovered that I am pregnant again. My husband and I agreed that having this child would tax our resources—financial, physical, and emotional—to the point of no return. Of course, that’s understating our reason for seeking an abortion. But I think you will agree that they are sound reasons.

The problem, of course, is that abortion is illegal, and I have no desire to attempt to do anything myself. So in my futile search in the local area for a duly licensed physician with a liberal outlook on such matters, I ran into someone who suggested that I write to you for help. I don’t know if there is anything of a positive nature that you can do for a person in my position, but I would be very grateful for any suggestions or information you can give me that may be of help. Thank you.

WOMAN 6: July 24, 1968. Seattle, Washington. It was brought to my attention that this association can give assistance to young women needing knowledge about the availability of obtaining an abortion. I have personally found myself in need of such information and greatly appreciate any help that you might provide. Due to circumstances and my strong belief against forced marriage, I am unable to bear the child and give it a name. I am a college graduate and established in the retailing business, and face loss of my job should this information get out and I attempt to bear this child out of wedlock. I am also aware of the increasing difficulty of placing children for adoption.

I cannot rescind my actions, but must save all those close to me from the consequences of my actions, and have concluded that an abortion is the only answer. My doctor has informed me that for my own safety and health, I must obtain an abortion at the earliest possible time and can wait no longer than a month. I need contacts very badly.

As for my own area, Seattle, I am at a loss and fear falling into the hands of a quack. Enclosed is a self-addressed, stamped envelope, also, a contribution to your association and its great work. I appreciate any and all help you might provide.

WOMAN 7: Niles, Illinois. Your name was given to me by the committee in Chicago that is fighting to legalize abortion in Illinois. I will be 40 in June, have two children—a son, 14 1/2, who had rheumatic fever at age eight and was hospitalized for four months; a daughter, 17, who had a bowel resection with removal of 24 inches of small intestine at 14. Both illnesses, as you may know, are likely to recur.

At age 12, I had identical surgery after a four-year illness. Now, both my daughter and I are plagued with constant and chronic illness. On July 8, 1968, I had my gallbladder removed after five years of intermittent attacks. We have lived in Niles only two years, and our modest home is mortgaged to the maximum. And we are in debt with remodeling bills and normal living wants.

My husband has just changed jobs, and my having to stop working would be certain financial hardship or bankruptcy. My husband and I love each other very much, and we dearly love and wanted the children we have. This unwanted pregnancy has created deep depression and anxiety for both of us, and hysterical sobbing on my part. Our entire family relationship has altered already in a matter of a few days.

I was told you would refer names and phone numbers of someone in this area who will perform an abortion. We could also manage to leave the state if necessary. My last menstrual period was approximately January 6. I’ve missed one period, and should be due for another about March 10. I’ve seen several doctors, and all have refused to even try to help me.

Writing this, I feel ashamed and desperate, yet hopeful. My husband is in full agreement for me to do whatever has to be done.

MAN 2: Los Angeles, California. February 29, 1968. I need your help very badly. Please get in touch with me as soon as you can. You do not know how much I will appreciate your advice.

My name is Guillermo. If you call me up, be sure not to mention this to anyone else at my home. Only to me. I will be waiting for your answer. Monday I will be home all day long—Monday, March 4. If you call before or after, leave me a message, please. Thank you very much.

WOMAN 8: Minneapolis, Minnesota. I am another unfortunate woman who’s come to face the hypocrisy and injustice of a country that leads in technology and sadly fails in humanism. I seek your assistance for the first time, but this will not be the first time that I’ve needed help. Believe me, for it was a matter of ignorance.

As you say, nothing is foolproof and some people have all the luck. Ironically, I stood by a good friend only a month ago, encouraging her with the experience that I had had, and I commend you, for your information dealt with everything possible, and that is good.

There are so many doubts. I’m three weeks pregnant. You’ve given hope and I shall try, in some way, to strengthen the cause.

WOMAN 9: February 23, 1968. Los Angeles, California. Would you please post me your most current list of doctors for legal abortions as soon as possible? I understand that the list also includes necessary information, such as fees, locations of offices, et cetera. I believe abortion should be legalized, and I am active in promoting that movement.

In the meantime, your list is invaluable to me right now, as I will not take the risks of an illegal abortion. I will respond to you after my trip to Mexico concerning the success of the venture. I was referred to you through a wonderful woman at the Free Clinic in Los Angeles.

WOMAN 10: September 25, 1968. Milwaukee, Wisconsin. Your organization has been recommended to me by a local physician who suggests that you might be of assistance. I’ve been widowed for six years and have a nine-year-old son. To have an illegitimate child now, I feel, would be unfair to my son. Granted, I should have considered this five weeks ago, but I didn’t, and there’s no point in recrimination at this late date.

I’m nearly five weeks pregnant and understand that you can supply me with the names of doctors in San Juan who will perform a legal, hospitalized operation. Naturally, I am interested in having the full details: cost, doctors’ names and addresses, how to contact them, et cetera.

Can you also please tell me both the earliest and the latest this operation can be safely undertaken? In view of my responsibility to my son, I would not pursue the matter further if I thought there were any danger to my life. I’d rather have the child than jeopardize my life, leaving my son alone at this age. Statistics prove how many butchers perform operations, and I want your reassurance that your organization will direct me to approved doctors and sterilized hospital conditions.

If all my doctor tells me of your group is accurate, I can only add that, in my opinion, you are saving lives, not taking them. My entire mental attitude changed and brightened when I realized that I could save my son this embarrassment and not endanger my life or reputation. How proud you must be of your work. If only more women knew about you.

MAN 3: March 29, 1968. Hollywood, California. My wife has been taking pills for several years. Two months ago, she was given a new series of the pills and was told that only the color was different. It turns out that the pills in this series contain only half a milligram, while her previous pills contain two and a half milligrams. She’s taken all of the pills as directed, but she has now missed her period for two months, and she is showing symptoms of pregnancy.

We will know very soon if she is, and we cannot possibly afford to have a child at this time. It would ruin us. I am deeply disturbed by the possibility that the anxiety of a pregnancy from my wife at this time might cause a severe emotional breakdown. She has a morbid fear of death, and she is deeply distressed that complications might set in with this pregnancy. We have discussed the possibility of abortion and have concluded that we will have to consider it.

Please send us all information available. We will gladly reimburse you if there is a charge. We are particularly concerned with pre-abortion and post-abortion procedures, and want to know what dangers are involved. We will sincerely appreciate your immediate reply, as she is pregnant, and this will be at least her eighth week.

WOMAN 11: August 9, 1968. Chicago, Illinois. I’ve taken your address from the files of the Planned Parenthood Association here. We have a sad case through our church responsibilities, in which a 17-year-old girl was raped and has become pregnant—five weeks now. Sadder still is the present attitude of Illinois law. Any information you can send us will be appreciated.

We would like to have any leads on someone in our area, if possible. Also, I understand you may have some literature on inducing a miscarriage. Don’t know whether you can send that through the mail. If so, please do. Would like names here or in Canada. Last, Mexico.

WOMAN 12: May 16, 1968. Corvallis, Oregon. I am in the necessity of writing you to ask for advice about the following problem. I am a foreign, single graduate student over 21 years old at Oregon State University and I’m facing the problem of being pregnant for about one and a half months.

Due to a circumstance, to begin with, the fact that it is not possible that I marry the man who would be the father of the baby, and other strong reasons, I cannot want to have the baby, and have decided that an abortion is the only way of avoiding this problem, to become even more unhappy. I have gone to doctor here. But he told me that abortion was not legalized, and that he did not know about the possibility of doing it.

Now, I have been told of your association. So I’m asking advice as to how I can have an abortion done soon. I would be very grateful of hearing from you as soon as possible. You can call me collect.

WOMAN 13: February 27, 1968. Seattle, Washington. I have, by my own ignorance, brought myself into a very unfortunate and unwanted pregnancy. I’m fully aware of the responsibilities when I wish to obtain an abortion. To me, this is no easy way out, but it is the way which will bring this unhappiness to less people. Once I have reached this decision, I wish there was a decent and proper way I could go about it, and I shall be very grateful to receive your help.

WOMAN 14: July 17, 1968. Palo Alto, California. I heard your talk on the radio this last Sunday, and need your help. Could you send me the list that gives the addresses of the doctors in Mexico? All that my boyfriend and I can get together is $150. Will they possibly do it for this amount? What were the addresses of those clinics where they gave a pregnancy test free?

I know I must not be far along. About four weeks is all. How long will the abortion take? My boyfriend is afraid I’ll be hurt by a doctor. Didn’t you say it was relatively safe? Do you need your birth certificate to cross the border? I hope you can help me.

My parents would be heartbroken. You see, I have a little brother who just turned five, who is dying of a brain tumor. All they need to just about kill them would be to find out about me. They’ve been looking forward for my going to college, and I don’t want to disappoint them. Please help me, and I’ll help you. Thank you for your time.

Please don’t put a return address on your envelope when you answer me. Thank you.

MAN 4: Phoenix, Arizona. Several months ago I telephoned you to offer, quietly, my services as a gynecologist. I’m deeply concerned with the problems of today, but I cannot serve, except discreetly. If I’m found out, I have a great deal to lose. So I’m available until then, or until our laws change. I charge very little. It is a minor surgery at most. I’m still available, but must remain. Yours truly.

WOMAN 15: March 6, 1968. Oak Park, Michigan. I’m in desperate need of help. I’m a married woman, 38 years old, and a mother of three boys, ranging in age from 14 years old to the youngest who was just 3 years old in February. Yesterday, I was informed by my doctor that I’m apparently seven weeks pregnant, and I feel despaired and lost over the impending thought of undergoing another pregnancy and birth.

After much thought and discussion with my husband, we both emphatically agree to have this pregnancy terminated as soon as possible. And not knowing whom to consult in this matter, we discussed it with our doctor, who in turn referred us to your organization, which he says he learned about on a local TV show, the Lou Gordon show.

We are in desperate need of an organization or person in our area, Detroit, Michigan, which is in a position to help us in having this pregnancy terminated as soon as possible. We urgently request your help in this matter, and we’ll be happy and grateful to cooperate with your organization in any way possible. If any further information is required by you or your organization, you may call us collect any time, and we will be happy to answer or do anything you require. We are hopefully awaiting a favorable answer from you in the very near future.

WOMAN 16: A friend gave me your name and address in hopes that you might be able to help me or give me some information on getting an abortion. I’m 10 weeks along now and haven’t much time. So it’s urgent that I know as soon as possible. Due to financial problems, because I work, I’d be unable to go out of town, and hope that you might know of someone in San Diego or the general area to help me.

There is a doctor here that I have been to already who said, legitimately, he could help me if I were to start spotting or bleeding. So all I need would be someone to start me, and the rest could be done in the hospital, where my medical insurance would cover the charges of having a miscarriage.

I would appreciate it, anything that you can do for me. And please do not post-return this address or letter, as I live with my family, and they know nothing about it.

WOMAN 17: January 29, 1968. I've heard about you in the past through my reading of The Realist and the Free Press. I have a four-month baby girl who was born out of wedlock and went through a great deal of emotional anguish about the possibility of giving up the baby for adoption. It happens that the baby was born four weeks prematurely, and right at the time when the father was visiting Los Angeles while on leave from the armed forces.

I imagined he was moved and shocked when he saw the helpless child lying in the incubator and clinging to life. I think maybe out of guilt he influenced me not to give her up for adoption. I guess this is what I secretly wished he would do. He has been helping me for the child support.

He came home in another leave for Christmas 1967, and I committed the stupidity of becoming involved with him. I hope he had some love for me, but what a mistake. Now I find myself pregnant again and considering the only way out: to have an abortion. I went to the doctor who examined me, and the pregnancy test is positive.

MAN 5: Sierra Madre, California. My wife became pregnant, despite our precautions, about four weeks ago. We don’t want this baby because we already have three small children, and four would be too many for us to care for properly. My wife is in good health and our doctor refuses to perform an abortion.

We were told you could inform us on how to obtain an abortion in Mexico. We would appreciate this information or, of course, any other information that might help us.

WOMAN 18: Goleta, California. Some months ago, I saw and heard you on television. I was completely in full accord with you and all your views regarding legalized abortion. Such courage is rare, to speak out as you do.

Now I find myself in the unhappy position of an unwanted pregnancy. We have two children and cannot afford a third. My husband and I are not the happiest married couple on earth, and this is the last thing that is needed in this family. I have just started my second daughter in school, and I’m now employed for the first time in eight and a half years of marriage. I love my job and don’t want to give it up. And I will have to if my pregnancy cannot be discontinued.

A very good friend gave me this San Francisco address to contact you. I hope you can help me locate a doctor who will perform the abortion for me. I appreciate your earliest possible reply.

WOMAN 19: May 23, 1969. Garden Grove, California. I’ve been informed that your association might be able to help people that are in drastic trouble. I find myself pregnant, I’m unwed, and have two children, ages 13 and 14, by my ex-husband.

Since I am the sole support of my family, I am obliged to work for a living, and this pregnancy would have dire consequences on my well-being and the well-being of my two children. If there is some help available, I am for speedy action, since I am, at this writing, two and a half weeks overdue.

WOMAN 20: February 8, 1968. British Columbia, Canada. I find it very difficult to know where to start. I am six weeks pregnant, and I’m just about out of my mind. I’m 43 years of age, a happily married woman with three teenage children. I have a part-time job, which has given me a new lease on life. And now this.