Art in Chicago, 1945–1995

Featured images

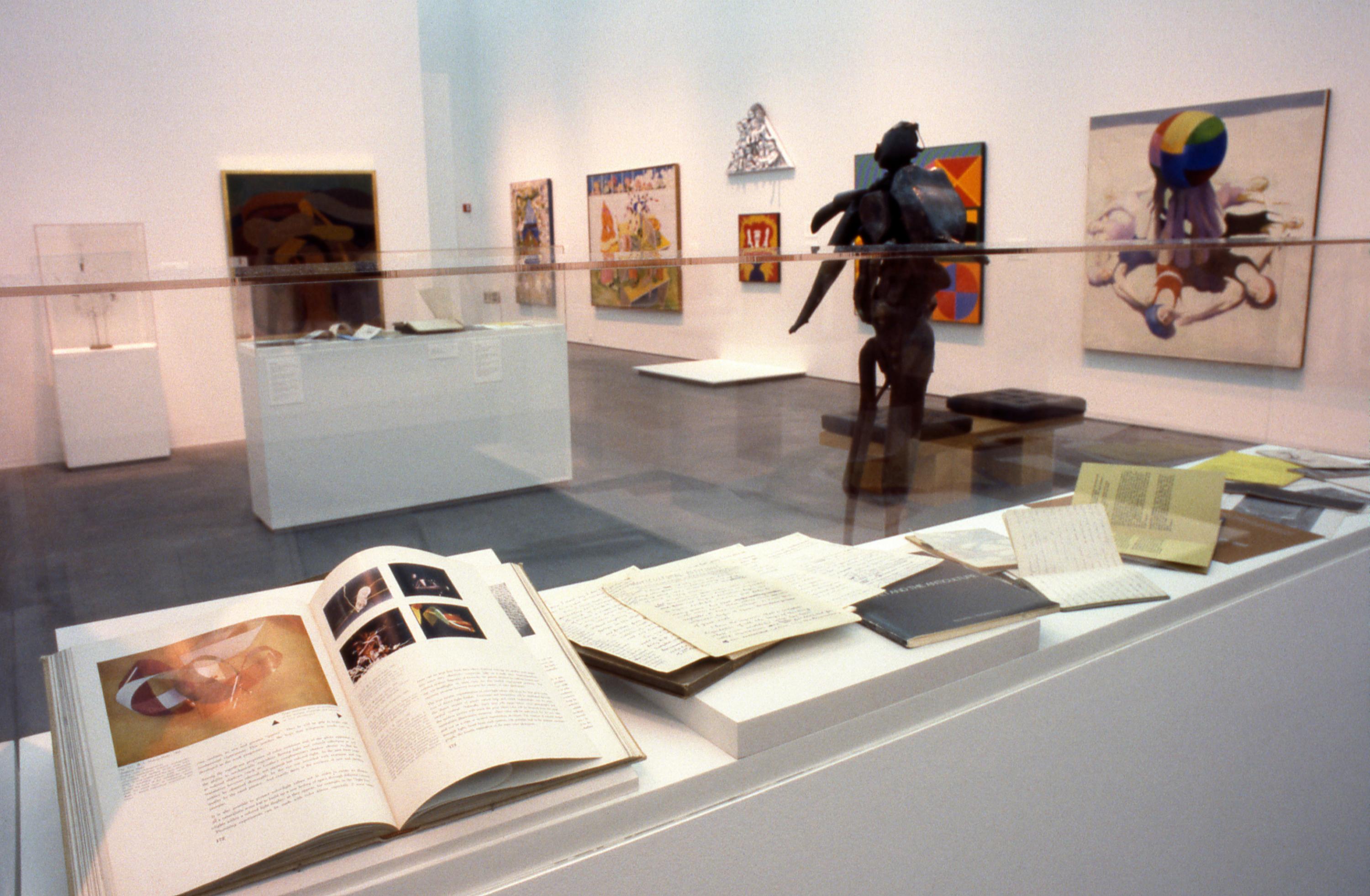

Installation view, Art In Chicago, 1945-1995, MCA Chicago

Photo: Joe Ziolkowski, © MCA Chicago

Installation view, Art In Chicago, 1945-1995, MCA Chicago

Photo: Joe Ziolkowski, © MCA Chicago

Installation view, Art In Chicago, 1945-1995, MCA Chicago

Photo: Joe Ziolkowski, © MCA Chicago

Installation view, Art In Chicago, 1945-1995, MCA Chicago

Photo: Joe Ziolkowski, © MCA Chicago

Installation view, Art In Chicago, 1945-1995, MCA Chicago

Photo: Joe Ziolkowski, © MCA ChicagoAbout the Exhibition

A Decade of Momentum: 1945 - 1956

The excursion begins in 1945 with Hungarian emigre László Moholy-Nagy and the students of his Institute of Design (ID), a school dedicated to enhancing all aspects of life through quality art and design. Also active and quite vocal during the immediate postwar years were the students of the more traditional School of The Art Institute of Chicago, who along with some of their ID peers, organized an artists' group called "Momentum" to protest exhibition policy at the venerable Art Institute of Chicago.

The sheer number of artists in Chicago increased significantly when returning soldiers used the GI Bill to enroll in educational institutions, including the city's art schools. In Chicago, commercial support networks began to expand - galleries opened, Chicago artists began showing their work alongside widely known artists from around the world, and local collectors became aware of the art being produced in their own city. A number of these artists received national attention; some remained in Chicago, while others left to seek their fortune elsewhere, fulfilling novelist Walter Sherwood's doleful analysis that "as soon as a Chicago artist won his spurs he packed his paint kit and took a fast train to New York." The two strains of Chicago art-making can be seen in this segment: expressive, and often distorted, figure-based work as well as experimental abstraction.

The Second City Rises: 1957 - 1965

The journey continues through the end of the 1950s and 1960s, as many artists’ careers developed, generating the sense that Chicago could in fact sustain a fruitful art community. A handful of influential commercial galleries, as well as a few artist-run spaces devoted to the promotion of a specific style opened, increasing exhibition opportunities for local artists as well as artists from abroad.The influx of new faculty and graduating students augmented the population of artists in the city.

At ID, the evolution of a Chicago School of Photography continued, producing several photographers, including Barbara Crane, Yasuhiro Ishimoto, and Kenneth Josephson, who became influential as teachers and eventually spread the ID approach. A group of artists, including Leon Golub, Seymour Rosofsky, and H. C. Westermann, most of whom were active in the previous decade, became known as the "Monster Roster", a moniker taken from the Chicago Bears' nickname, the Monsters of the Midway, and a reference to the group's frequent use of distorted imagery in their art.

Their style, characterized both by an adherence to the figure, often in fragmented form, and a psychologically charged dreamlike state, became synonymous with Chicago art, though a number of artists practiced other styles, notably an abstract mode of painting largely based on organic forms. This phenomenon recurs in the future, with new approaches, new names, and new definitions of the "Chicago style".

The Entry of the Imagists: 1966 - 1976

At the end of the 1960s, a group of local artists became known as the imagists, so-called for their use of the human form, which they often rendered in a misshapen or humorous manner with aggressive colors and a nod to popular culture.The imagists were first shown in the now legendary, innovative exhibitions organized by Don Baum at the Hyde Park Art Center.These artists were highly publicized and began to exhibit their work around the world. "The Entry of the Imagists into Chicago," a section chronicling the years 1966-1976, includes a special time capsule that re-creates the unconventional installation of the third Hairy Who exhibition, which included linoleum-covered walls.

Forms of abstract and conceptual art also appeared during this period, the latter becoming more popular and developed in the years to come. Artists established cooperative galleries, many supported by the newly created National Endowment for the Arts, which allowed young artists exhibition opportunities. The turbulent climate of the late 1960s also motivated many artists to address such pressing social issues as the Vietnam War and racial equality. Artists who took on the roles of activist and social commentator are examined in the "1968 Room," alongside the art community's response to the riots and happenings at the 1968 Democratic Convention, for which Chicago was the host. A video work, commissioned for this exhibition, presents artists' visual statements juxtaposed with documentary footage from this period.

The Big Picture: 1977 - 1985

The name of this segment, "The Big Picture," refers to Chicago's pluralistic art scene during this period, reflecting the varied artistic climate of the 1970s. Following the lead of their predecessors, artists in Chicago had taken matters into their own hands and formed several alternative spaces to exhibit their works in the early 1970s. These feminist cooperatives and artist-run venues provided a wider diversity (and a greater number) of artists the chance to expose their work to a broader public. A school of large-scale sculpture, often called the Prairie School, developed in Chicago with the establishment of a gallery equipped for its fabrication. Artists continued to explore more theoretical avenues concerned with questioning the definition of art as well as individual and social identity.

This eclecticism is manifest in the lively Black Light-Planet Picasso art party, partially re-created in this segment, an exhibition/festivity organized by artists in their own loft, displaying their large-scale, fluorescent paintings under black light, in the midst of New Wave music. In 1980 Chicago staged its first International Art Exposition, bringing an international audience to the Midwest. This corresponded with the beginnings of the art boom of the 1980s, which had a profound effect on Chicago’s art community, as it did around the nation.

(Un)Assigned Identities: 1986 - 1995

The exhibition concludes with the most recent decade, 1986-1995, presenting the greatest number of artists in the growth of the city’s art community. Expansion continued at a rapid rate in the late 1980s. Artists working in Chicago were being exhibited at unprecedented rates at River North galleries, not-for-profit alternative spaces, university galleries, and the larger institutions, including the Art Institute. A generation of young artists based in Chicago, including Jeanne Dunning, Hirsch Perlman, and Tony Tasset, developed ways of thinking about and making art that used contemporary literary and philosophic theory, particularly that which is associated with the study of language systems and psychoanalysis. In addition, established and emerging artists kept alive the long tradition of figurative painting, and figurative work still received significant attention at mainstream art institutions.

Many artists took advantage of international exhibition opportunities. These artists did not necessarily identify themselves with any particular geographic location, making the designation "Chicago artist" more or less obsolete. Identity issues such as this, along with complex notions about cultural and sexual identity, became major topics of interest in the 1990s. The art community was more inclusive than ever before; an expanding local and international audience began to view the work of an increasingly diverse group of artists, many of them working with new types of media.