Dan Flavin: Pink and Gold

Images

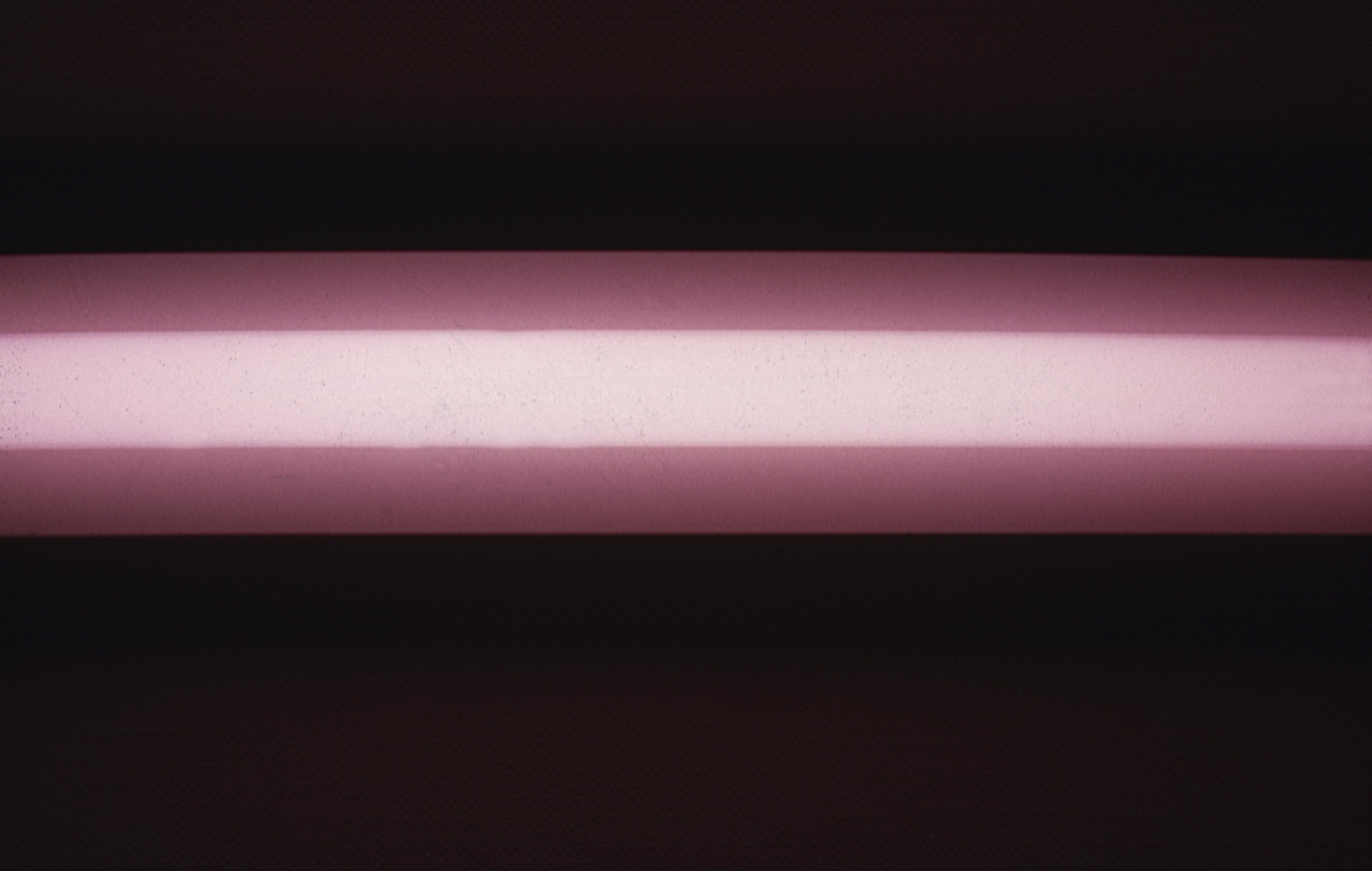

Installation view, Dan Flavin: Pink and Gold, MCA Chicago

Photo: David Van Riper © MCA Chicago

Installation view,Dan Flavin: Pink and Gold, MCA Chicago

Photo: David Van Riper © MCA Chicago

Installation view,Dan Flavin: Pink and Gold, MCA Chicago

Photo: David Van Riper © MCA Chicago

Installation view,Dan Flavin: Pink and Gold, MCA Chicago

Photo: David Van Riper © MCA Chicago

Installation view,Dan Flavin: Pink and Gold, MCA Chicago

Photo: David Van Riper © MCA Chicago

Installation view,Dan Flavin: Pink and Gold, MCA Chicago

Photo: David Van Riper © MCA Chicago

Installation view,Dan Flavin: Pink and Gold, MCA Chicago

Photo: David Van Riper © MCA ChicagoAbout

The MCA's fourth exhibition, Dan Flavin: Pink and Gold, presented an expansive installation by Dan Flavin (American, 1933–1996), giving the groundbreaking artist his first solo museum exhibition and his very first showing in Chicago. In the installation, titled alternating pink and “gold,” 54 eight-foot-tall florescent light tubes alternating in pink and yellow were installed vertically across the six wall spaces of the museum at intervals of two, four, and six feet. As part of the exhibition, visitors were invited to feed pre-punched paper cards containing data through a rented IBM 1401 decimal computer {bio: (one of the first commercially affordable computers used by businesses from the 1950s–1970s) to print out personalized exhibition catalogues.

Taking equal influence from the constructivist industrial sculptures of Vladimir Tatlin (Russian, 1885–1953)} and the critique of consumer society and traditional artistry offered by Marcel Duchamp's (French, 1887–1968) ready-made pieces, Flavin's light installations worked to denaturalize taken-for-granted commodity objects like light bulbs and the phenomena they produce. Viewing his own pieces and artificial lighting as a “modern technological fetish,” Flavin's work pried entirely replaceable commodity products, like florescent lighting, from their standard context—placing them in the gallery space for the purposes of critical enquiry. As the conceptual artist and writer Dan Graham (American, b. 1949) notes, Flavin's work reduces “fine art to quasifunctional (or nonfunctional) décor” when it reflexively refers back to the gallery. The lighting system “literally makes the works visible” realizing the gallery itself as a function of the art by illuminating it. His placement and presentation of the bulbs also reduces them to signify, at once, their own objecthood, the effect they produce and the corporations that produced them, while attempting to remove them from the “symbolic” “transcendental” and allegorical impulses traditionally associated with artistic creation. In a statement about Flavin’s formative 1964 exhibition Some Light at the Kaymar Gallery, the famed minimalist sculptor Donald Judd (American, 1928–1994) explains, “the lights are untransformed. There are no symbolic transcendental redeeming or monetary added values present.”

In the same vein of thought, the exhibition's catalogue, and the computer that produced it, functioned as an additional and conceptually relevant aspect of the show. The decision by both Flavin and the MCA director Jan van der Marck to include the IBM computer stands as an anomaly in Flavin's oeuvre, as he rarely utilized commercial technology beyond fluorescent lighting in any of his exhibitions. This catalogue featured entries by Flavin's associates like the Dan Graham and Donald Judd, and quotations from the critic and philosopher Roland Barthes (French, 1915–1980), along with a comprehensive diagram detailing the layout of the exhibition and instructions for the installation of the light tubes. Holding interesting parallels to the usage of commercial IBM technology by members of the Fluxus movement like George Maciunas (Lithuanian, 1931–1978), the application of the computer in Pink and “Gold” functioned in line with Flavin's other conceptual aspirations. As a piece of standardized commercial technology often used in banal, corporate settings (like florescent light tubes) the catalogues produced by the machine were meant to be equally interchangeable, commodified, and serially produced. One reason Flavin may have never ventured to use similar technology in his work again is the fact that he was so disappointed with the production quality of the catalogues themselves. Unlike the pristine, identical appearances of his light installations, the catalogues were often irregular in appearance—containing unique attributes like different orientations, paper types, spacing errors and missing words.

Just as the “gold” in the title of the show plays on the industry name for the cadmium yellow used to modify the light bulbs, this exhibition explored the serialized and commodified aspects of technological development, artistic production, and the space of the gallery.

The simplicity of its shape should not be equated with with simplicity of experience.

Dan Flavin: Pink And Gold, 1967–1968

Pink and "Gold" is an indoor routine of 54 strips of fluorescent light, spread in serial progression, over six of the museum's walls.

Dan Flavin: Pink And Gold, 1967–1968

Funding

Dan Flavin: Pink and Gold was funded in part by Commonwealth Edison.