A People’s Art History: An Open Letter

Featured images

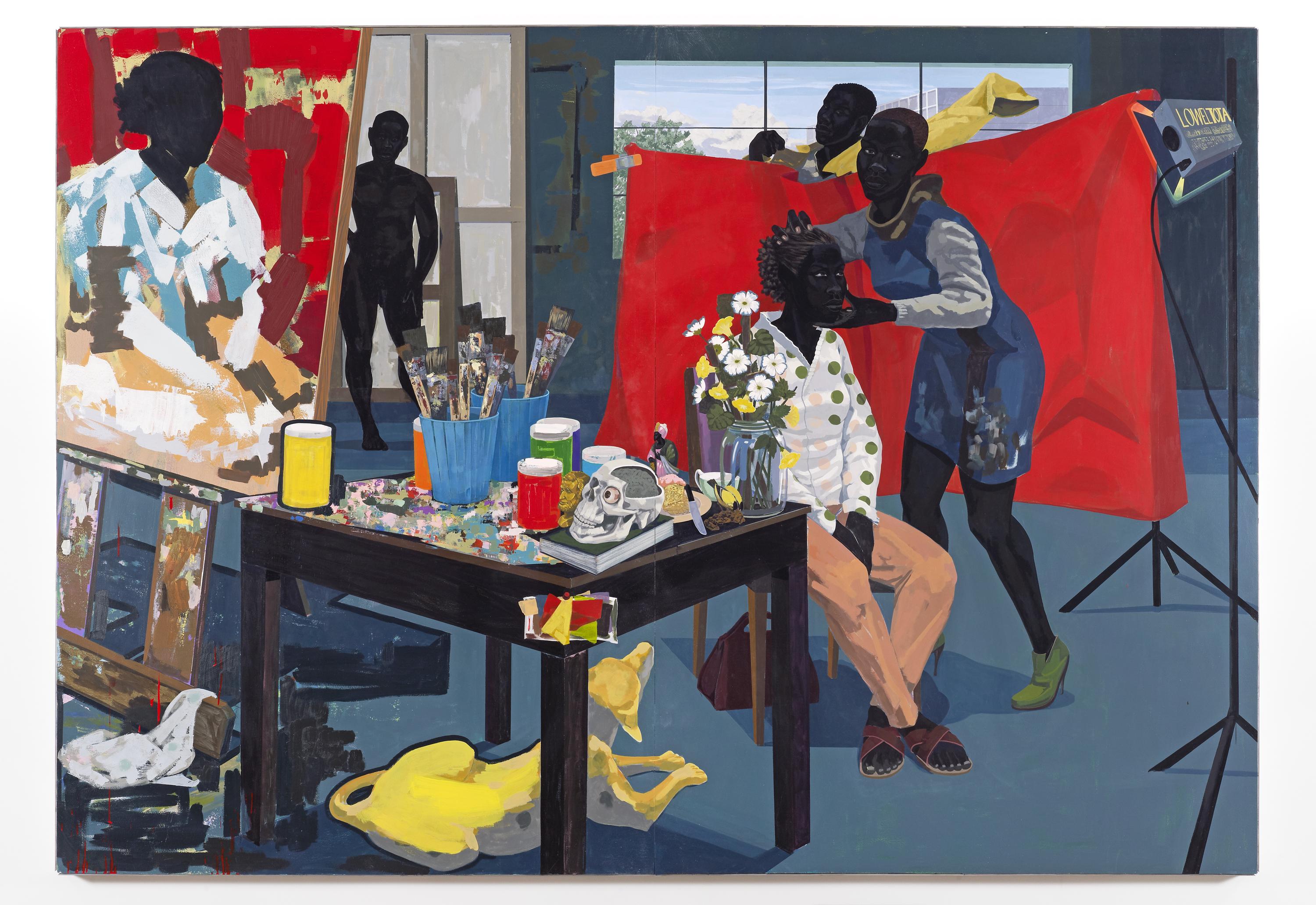

Kerry James Marshall, Untitled (Studio), 2014. Acrylic on PVC panel; 83 ½ x 118 7/8 in.

(212.1 x 301.9 cm). Lent by The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Purchase, The Jacques and Natasha Gelman Foundation Gift, Acquisitions Fund and The Metropolitan Museum of Art Multicultrual Audience Development Initiative Gift, 2015

blog intro

As we were preparing for the Kerry James Marshall exhibition, we asked several artists, art historians, and curators to fill in the gaps or alter the stories of an art history textbook. Today we share Alexandria Eregby's open letter, written for the project.

An open letter.

If you are reading this, you have likely engaged in an amazing series of textbook interventions, inspired by the marvelous and masterful Chicago-based painter, Kerry James Marshall. I, too was invited by the MCA to intervene in this art textbook exercise amongst that talented cohort of artists.

As you can tell, my participation in this project was not so similar to my peers. I’ll be the first to admit that this project was a difficult task for me. I struggled to pinpoint a direction that excited me. When it came down to actually engaging with the text, I didn’t want anything to do with it. I have a couple theories, (or perhaps a few excuses) to offer. This letter serves as a reflection of my thinking process for those who are willing to listen.

on family history

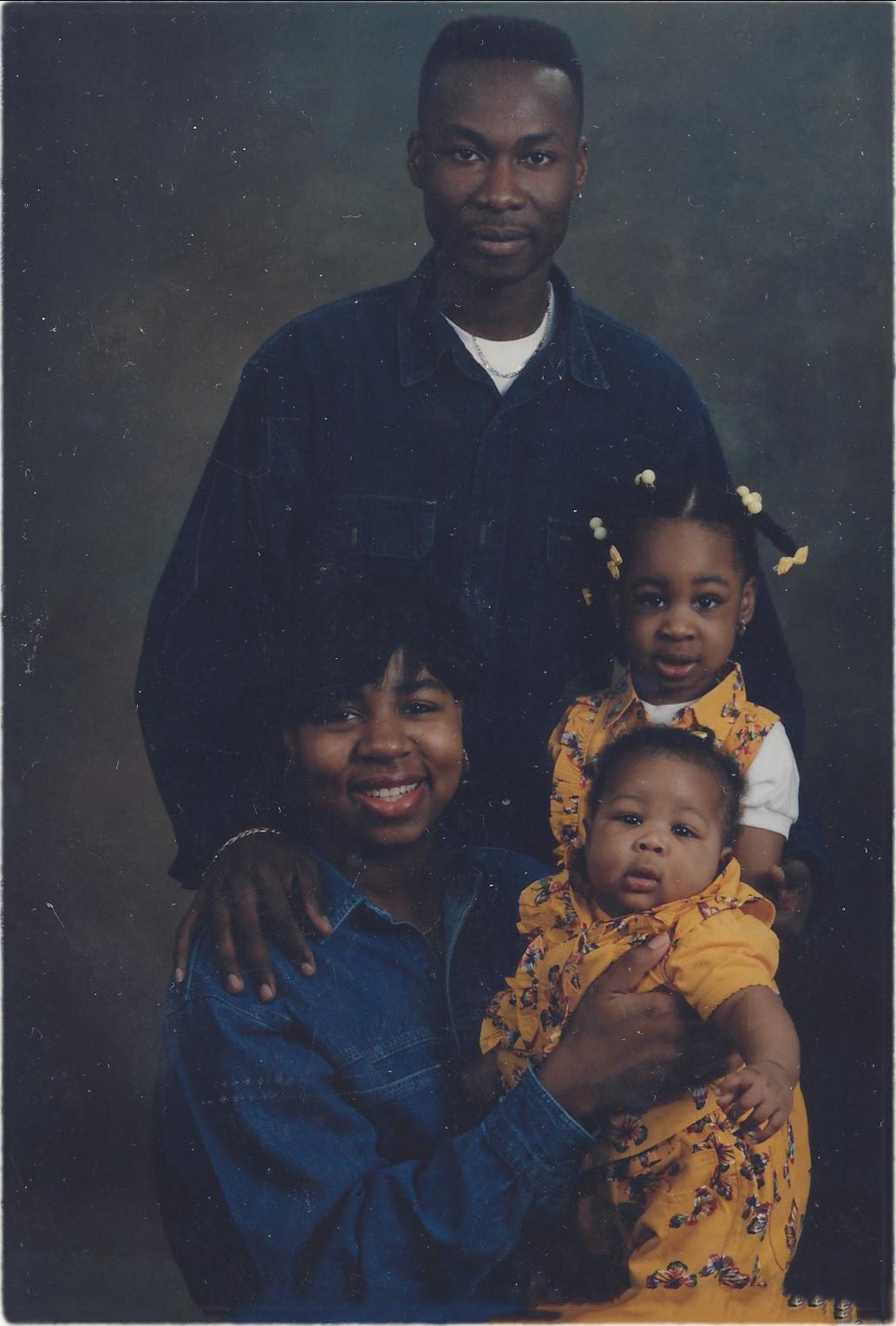

This is my family.

I come from a lineage of 3 generations of Chicago Westsiders by way of Brookport, Illinois. My Nigerian father, immigrated to the United States from Port Harcourt, just a few years prior to my birth, to run track and field.

History beyond the oldest living Shelton or oldest living Eregbu, has not so much been a right, but a privilege for me and my people that has been rather challenging to preserve. My mother’s side—likely once sharecroppers, and prior to that, slaves. My assumption of this is based on what I know of my family’s migration pattern from the rural parts of Tennessee, to the rural parts of Illinois. When the Great Migration hit, and my great-grandparents Milford and Leva Mae Shelton’s family started to expand, the two had to pick up their lives from the old country and transition to city living. I only know this because at one point in my life, I was desperate enough to partake in some searches on ancestry.com and was able to find some old census papers, which documented my great-grandfather’s move. No one knows anything on my mother’s side, beyond my great-grandfather’s parents. And my nearly 90-year-old great-grandmother, Geegee, unfortunately does not care to speak much on her childhood (which to be honest didn’t last very long because she met my great-grandfather Pawpaw at 14 years old) since her parents weren’t too active in her life.

on art history

By now you might be thinking to yourself, “Well at least you know where your dad is from.” However, I regret to admit that the story does not end there. My father was born in the year of 1969, just at the brink of the end of the Biafra war in Nigeria. This war, which broke out only 3 years after Nigeria had finally gained independence from British rule, killed over tens of thousands Igbo people— in attempt to stomp out almost an entire culture over land and territory. People were slaughtered, villages were burnt down to the ground. Postwar trauma and fear that one day such a bloody moment in history would return again, caused several families, including my own, to flee from Nigeria, as soon as they were able. When my father arrived to the States, while he maintained a strong sense of pride and nationalism, certain of aspects of his culture began to fade, as he realized intensity of being a Black successful man in predominantly white spaces. Consequently, traditional garments and speaking Igbo in public were replaced by athletic wear and words like “dude” or “bro.” My younger sister and I were never taught Igbo either. To this day, I’m not entirely sure why, but given the sociopolitical climate of the United States in the 90’s I can certainly come up with an educated guess.

Erasure is the through line here. Ownership and cultural preservation have been fantasies, at best, due to a long cycle of violence and systemic oppression, which has attempted to stomp my people out. Need proof? Go to your local museum. How often do you see a wing or department fully dedicated to Black American art, design, or furniture before 1960? In the African Art wing (if your museum has one) I can guarantee that the art from Nigeria will mostly be Yoruba, not Igbo. Want to know why? Because genocide. The Igbo people of

Nigeria are still working to revitalize their cultural history nearly 50 years later. And Black folks in America are still working on maintaining affordable housing, let alone art and other culturally significant hallmarks.

This is not a sob story. My people have persevered, and I, too have persevered— even in the most difficult of times when it felt as though I was nothing more than a wanderer in the dark. Black people across the world have frequently been at the forefront of popular culture and innovation, somehow managing to rebuild and rebirth in the face of destruction. It’s quite an incredible thing to realize actually. Even more fascinating of an experience to participate in. I am proud to be apart of such a movement of people.

Ok. So what does this have to do with art or art history?

The textbook that I was assigned, Gardner’s Art History through the Ages: A Global History, written by Fred S. Kleiner—was composed of over 1,000 pages of text and 36 chapters on art across the world, beginning with Paleolithic art to postmodernist art after 1945. Of these 36 chapters, only 3 were dedicated to African art practices, for a whomping number of 54 pages. 24 of those pages were focused on Egyptian art, while the remaining 30 pages were divided by "Chapter 15: Africa Before 1800" and "Chapter 34: Africa after 1800." In the final anecdote, "Chapter 36: Europe and America After 1945," not a single Black artist was mentioned. Of the 13 artists featured, only 4 of them were women. Flipping through the pages of this text, I am suddenly transported back to my first year of college as an undergrad, attending one of the top 3 art schools in the nation, only to discover that its diversity numbers are almost just as appalling as this textbook's. I think of the numerous times where I wanted to take a course in African or African American Art History and was unable to, because the enrollment was too low. I replay over and over again, the instances where I had to learn and absorb the famous White artists whose work I cared nothing about, but were relevant to my peers, because such artists were making millions off of cheap labor, shallow ideas, and tacky reproductions. Meanwhile I'm trying to explain during critique that no, the subject represented in my painting is not Rihanna but contemporary work of Mickalene Thomas (yes, that actually happened). Outside of the education system, the ratio of men to women in galleries and museums almost mirrors 13:4, even though I know for a fact that at my alma mater, women students outnumbered men, if not 3:1 then 2:1.

These are the realities of the world I operate in—where patriarchy, marginalization, and tokenism battle to coexist under the roof of capitalism. While harsh at times, I accept them because I know in some ways as a young, educated and Black woman, that I benefit from these things, as much as I hate to admit it.

That being said, the pain, exhaustion, and embarrassment that I have frequently encountered for having to explain to others as to why I deserve to sit at the table, or why representations of voices similar to mine should be included in conversations at very least, has been daunting. Especially considering the lack of resources and extra labor I have had to put in, just to identify individuals like myself, who have been here, in this position before.

The feeling of voicelessness or lacking representation is not something I would wish for anyone, yet it’s something that I’m sure my children and my children’s children will encounter as racism, sexism, classism, and discrimination become more cryptic, and media and our ability to interpret images becomes more advanced (or not so advanced). I’m not sure anymore.

People need to see representations of themselves in the world, as a reminder that they are not alone. Loneliness and confinement will cause people to do both wondrous and terrifying things. I think about how important my parent’s copy of Norman Rockwell’s painting of Ruby Bridges was for me as a child, after I learned of her bravery in the sixties to be the first African American child to attend an all white school in Arkansas, at age 6. Similarly I attended a predominately white school as a child between the ages of 6 and 22 years old. Her image hanging on the walls of my family’s home, was a subtle reminder that my story could also end up a profound once, if I remained encouraged and stayed my given course.

This is why Kerry James Marshall’s work is so important. This is why the MCA’s attempt to open up the discourse of art history and who gets to participate in it, is also very noteworthy.

So why did I struggle with this commission? Why was this prompt so difficult for me to complete?

It is important to note here, that my intention to drive diversity in institutional spaces has never been to exclude or erase the presence of anyone else. Rather, my argument has always been that these merging and disparate identities, should be able to share space peacefully. While I find it terribly unfair and problematic that a white man Fred S. Kleiner gets to literally write the history for several different cultures across the globe from the be beginning of time until now—(granted, I’ll admit, I know nothing about this man beyond his bio, and I’m sure he is a nice guy)—I take issue with the thought of me going in and destroying a textbook that does make some attempt to preserve someone else’s history (regardless of whether it’s inclusive or not) to amend it with my own. Perhaps I’m too sensitive of a person, or perhaps my background in working with materials has warped my perception of the potency of this message. Either way, there’s something about this gesture that seems too colonistic to me. Each time I attempted to cut away at the images of modernist artworks that bore more or traditional works that were representative of someone else’s culture—I got more discouraged and the process to conceive a work of art seemed more contrived. When I thought of gluing into the book or adding an additional section, it was the same thing—I recalled the history of my mother and her mother’s mother, my father, and his people. I understand that my issue, in this case, is a deeply personal one and because I’m not quite sure how to fully resolve it, I decided to take to the pen and paper and write about it here. I believe that it is my job as both an artist and educator not to provide answers, but to pose questions that can be addressed on multiple planes, by several voices. It could be said, that my biggest qualm with Kleiner’s work and the MCA’s prompt was the 1:1 ratio. Who is Kleiner to determine the learned history of so many people, and not do the work of including more history of the very same people his ancestors likely destroyed? Who then, am I to come in and do the same?

- Sincerely,

Alexandria Eregbu

Note

This post was directly transposed from a typed letter sent to the museum.